An elderly gentleman from another era, wearing a jacket, bow tie, fedora and walking stick, looks up to observe on the scaffolding a young artist convulsively tracing strange figures on a wall with his brush to the rhythm of hip hop music . He looks on in astonishment for a few minutes, then leaves that strange encounter behind and walks away; before he exits the scene, someone asks him if he appreciates, and with his index finger he signals no. This is how director Andrea Soldani ’s short documentary closes, which, conceived as a music clip (the ones that young people of a few decades ago devoured, so much so that they are often remembered as the “Mtv generation”) testifies to the extraordinary genesis of the work Tuttomondo, perhaps the most famous mural in Italy, that Keith Haring (Reading, 1958 - New York, 1990) made in Pisa in 1989. It almost seems like a metaphor for the past giving way to the future, and indeed the whole operation seems to take on these comparative values: an exponent of pop art, indebted in his style to graffiti art, among the first street artists in history, finds himself making a gigantic mural in one of the most history-laden thousand-year-old historic and monumental centers in Italy, and moreover on an exterior wall of a convent.

This is one of those events in art that has the unbelievable, to which we should add, moreover, that besides being the only wall work conceived by the artist to last over time, it was also one of Keith Haring’s last and most heartfelt works, read as a sort of pictorial testament. The artist would in fact die shortly thereafter, at less than 32 years old, snatched from life by AIDS, which mowed down many young people of his generation. Today, the work is one of the most visited attractions in Pisa, some say just behind the Leaning Tower. It can be found in numerous art history books and manuals, documentaries, in-depth studies and exhibitions have been dedicated to it, but its realization was certainly not a foregone conclusion, all the more so when one thinks of a world, the Italian and even more so the provincial world, that knew little or nothing about street art. But the way in which its crazy yet far-sighted realization was arrived at is something truly extraordinary.

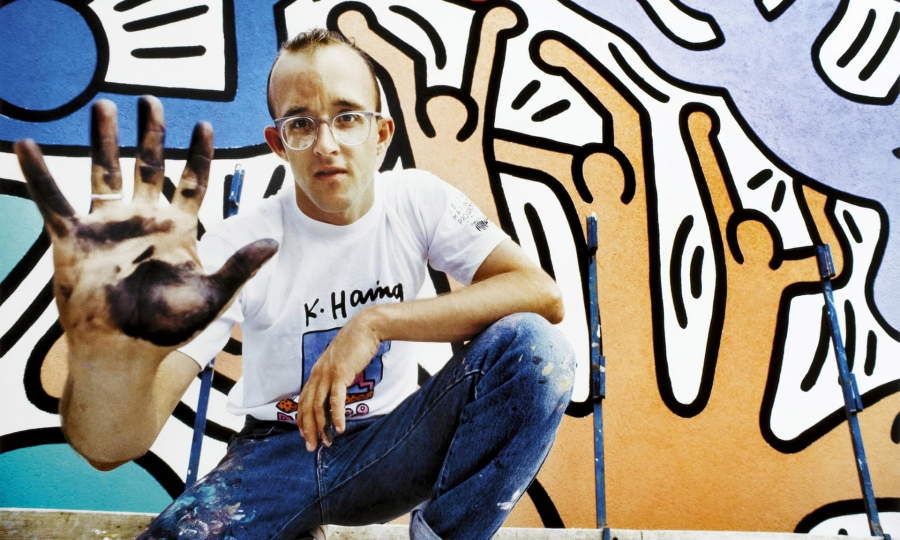

In 1987, Piergiorgio Castellani, a student from Pontedera is in New York following his father, also a university student, who is traveling to finish his thesis on the Hare Krishna spiritual movement. The two are on a Manhattan sidewalk observing a group chanting a mantra from a pickup truck when the young man notices that also spectating is that unmistakable lanky figure of Keith Haring, the artist of the moment, who is making a name for himself all over the world from the United States. Piergiorgio recognizes him immediately because, as chance would have it, he is a subscriber to Interview, a magazine created by Andy Warhol, a close friend of Haring’s, who had often hosted contributions on the artist. Helped by his father, Piergiorgio plucked up the courage and approached Haring, showing an in-depth knowledge of his production: the work in São Paulo, the 300 meters of painting on the Berlin Wall, but he also pointed out that in Italy, with the exception of some of his spontaneous interventions in Rome, destined not to last, and those for the Fiorucci store painted between 1983 and 1984, there is no real public work of his accessible to all.

The humility of the artist, who was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, and probably his amazement at a guy who lives on the other side of the world and knows everything about him, convinced him to listen, so Keith Haring made an appointment with him in his studio, now the headquarters of the foundation that bears his name.

Haring seems fascinated by the idea of making something in Italy, perhaps because of his love for art, of which the Belpaese overflows, perhaps because that same year he found out that he had contracted ’AIDS, to which, at the time, there seemed to be no other way out but death, and he is ready to reconsider his priorities, including getting away from the New York star-system and its oppressive market.

A 20-year-old boy and his father carry on a real crusade to bring the project to fruition: initially they lean toward Florence, but it seems that, apart from a wall in the far suburbs, the administration is unwilling to concede anything else. But it happens then that, almost by a fortuitous conjunction of the stars, they manage to find the assent of a far-sighted alderman from Pisa, Lorenzo Bani, who agrees to advocate the operation even though there is no sketch, since Haring never makes any for his works, and then from there a domino of favorable coincidences: a wall is located, 180 square meters of unbroken surface, with neither doors nor windows, in the city center a few meters from the train station and even less from the bus station, a circumstance that intrigues the artist who had had his beginnings in the New York subway. Moreover, that wall is the exterior of the church of St. Anthony’s Convent, and this excites Haring who feels the experience of Henri Matisse, who among his last works signed the decoration of a church, is close by.

Father Luciano, pastor of St. Anthony’s and rector of the convent, says he is ready to host that work, even without knowing the outcome, as he is intrigued by an artist who speaks about social issues. The road seems to be downhill, except that the chosen wall is shabby and certainly not ready to accommodate the painting, and the municipality has already jumped through hoops to find ten million liras for such an intervention, earmarked for the artist’s travel and hospitality (which requires no cachet) and other expenses. Again the luck and vision of the local manager of Caparol, a dye manufacturer, intervenes, and sensing the opportunity of the matter, he manages to convince the head office in Germany to invest several million to build with state-of-the-art techniques the best surface for Haring’s painting, and also to make himself available to supply all the necessary technical material.

Although the superintendency, the critics and the city in general were rather skeptical about a blatantly contemporary artistic action that was going to fit into a historical context, it all came to fruition and in June 1989 Keith Haring arrived at Pisa’s Galilei Airport. Upon disembarking, Haring is taken to see the wall, and excitement assails him: a wall transformed into a canvas, so much so that he even remembers its grain, and a prime context make him feel a sense of responsibility. He asks for a couple of days so that he can best approach the work. At the Caparol headquarters in Uliveto Terme, he chooses the colors and brushes that are most congenial to him, and spends a few moments walking around the city, where he experiences the monuments, streets and squares, taking along his polaroid with which he steals shots, which will be the preparation for his work. Then he begins to work on the scaffolding several meters above the ground, working freehand, starting from the upper left corner and, as can be seen in the images in the documentary, pictographs come out of his sure hand, figures that from time to time intersect like pieces of a puzzle.

The event that had started quietly attracts more and more curious people to that funny figure who without a definite plan and accompanied by music works all day on the scaffolding. Not even illness stops him; he resides in the Hotel D’Azeglio, which at the time, as Haring recalls in his diary, was “directly opposite the wall, so I see him before I fall asleep and when I wake up. There’s always someone looking at it (I’ the other night even at 4 a.m.), it’s really interesting to see people’s reactions.” People keep pouring in, the intervention becomes a real happening, a party, and after the first two days when he composed that giant mosaic by himself to help him paint are involved then Caparol workers and students. In the meantime Haring is besieged, with great generosity he does not refuse to give away pins and shirts, to give autographs and even to draw on every surface that is offered to him, sheets, clothes and even a van, he accepts the church’s proposal and stays with the boys to draw.

The city began to respond and cheer him, and he reciprocated, still writing in his diary, “The people are really nice, sometimes a little aggressive, but basically sweet [...] the weather was beautiful and the food even better” and “Pisa is incredible, [...] the other night I had dinner with the friars and visited the chapel.” Father Luciano would also recall how Keith Haring, not religious or certainly not Catholic, had wanted to stay alone in the church.

The work is thus completed, all in a very few days: a precious fabric summing up some of his best-known symbols of the artist’s production, such as the radiant child symbolizing primal energy, a matryoshka of three figures of different colors, emblem of the diversities that coexist, theTV man, a mirror of those oh-so-medial times, the figure who loads a dolphin on his shoulders, a reference to nature; but also tributes to Pisa, such as the four little men who fused together form with their heads and arms the pomata cross, the historical symbol of the city.

The artist then confesses before the cameras, “I wanted to make something that the friars would accept as their own, many mystical symbols.” And indeed one notices a mother with a baby in her arms and a scissor man cutting the snake, the personification of evil. All this is rendered with color effects inferred from Polaroids that reference the city, the blues of the sky, the ochre yellows and light reds of the buildings. These instances are amalgamated within a context of great balance, without any hierarchical order and with a free reading, in a work that shows great calligraphic virtuosity and in dominating space.

That Haring spent his whole self on this work is also confirmed by his statements, “It is perhaps the most important wall I have done so far [...] up to this moment I have only painted temporary things but this should stay here for centuries.” The very title of the work Tuttomondo was suggested in the first person by the artist, despite the fact that he usually did not give names to his works.

The value that Haring’s work has taken on was summed up perfectly by Piergiorgio Castelli when he said that the American artist saw in the one in Pisa the great opportunity “to enclose in a public work, in such a special place, his spiritual and artistic testament, where he gathers all his iconography, gathers it in a great dance of life [..] to try to free his mind, his spirit from this looming fear, but at the same time to free a city like Pisa from its millennial history.” Not even eight months later, in fact, in February 1990 Keith Haring died, and we like to believe perhaps more peacefully, thanks to the making of Tuttomondo. Perhaps, Keith Haring not surprisingly wrote, “I am sitting on the balcony looking at the top of the Leaning Tower. It is really very beautiful here. If there is a heaven, I hope it looks like this.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.