The history of art is filled with extraordinary events, some of which are known to most, while others are less well known but no less fascinating and worthy of being told. These are vicissitudes involving artists who are considered minor, perhaps because they were unable to renew or modernize a style in a decisive way, or because they spent their existence far from the glory that befell their colleagues (which then ended up tarnishing their fame), or again because changes in taste caused their oblivion, or because their careers took place outside the great capitals of art, in small provincial towns. So it is not necessarily the case that small and little-known hamlets do not conceal incredible stories within their walls.

One such story is enshrined in a display case at the Glass Museum in Gambassi Terme, a small town of five thousand in the province of Florence, nestled in the hills of Valdelsa, amid centuries-old woods and widespread hot springs. On April 4, 1603, the town gave birth to Giovanni Gonnelli (Gambassi, 1603 - Rome, 1656), an artist destined to become one of the most singular sculptors of the seventeenth century. His father, Dionigi, was a glassmaker by profession, that is, more simply, he worked with glass: in this area of Tuscany glassmakers are known, by metonymy, precisely as bicchierai, since in the past production was linked above all to practical purposes and most of the artifacts were glasses or containers for oil and wine, produced in abundance on the Valdelsa hills. The art of glassmaking has been rooted in Gambassi since ancient times: documents attest to the production of glass since the 13th century, a time to which a document, dated 1276, informs us that eight furnaces were active in Gambassi and its immediate surroundings. Gambassi, in ancient times, rivaled Murano, and the most skilled and sought-after glassmakers were able to lead very comfortable lives. This is what happened to Dionigi Gonnelli, who is one of Gambassi’s most prized glassmakers. Little Giovanni could then devote himself without any problem to his passion, that of sculpture.

|

| The Glass Museum of Gambassi Terme |

|

| Giovanni Gonnelli known as the Blind Man of Gambassi, Self-portrait (kept until 1942 in a private collection in Sesto Fiorentino, then dispersed) |

The artist evidently could not stand the Mantuan climate any longer and decided to return to his homeland, where he stayed for some time. His fame, however, did not diminish, and in 1637 he moved to Rome, where he had the opportunity to work for Pope Urban VIII (born Maffeo Barberini, Florence, 1568 - Rome, 1644), executing a portrait of him that is now preserved in Palazzo Barberini. And in Rome itself, there are those who do not believe that those well-conducted works were the product of a blind man’s hand. So much so, Baldinucci again recounts, that Giovanni Gonnelli is put to the test. A “person of high business” then asks the sculptor to work inside a completely dark room, devoid of the slightest glow. However, the illustrious personage, not named by Baldinucci, must recant: the terracotta portrait that the artist executes in the dark is so beautiful and realistic that it “deserved the praise of the most beautiful that had ever come out of his hands until that day.”

The quality of Giovanni Gonnelli’s work so praised by contemporaries is well attested by the portrait of Urban VIII. The bust of the pontiff is rendered with exceptional naturalism and adherence to the pontiff’s real features, the details are delineated with great care, the expression denotes extraordinary vitality, and the modeling lends itself to very refined lighting effects. Can such a realistic work be the work of a blind sculptor? This is what scholars have wondered, divided between those who have taken the 1637 date for granted (there are in fact payments, recorded that year, attesting to the execution of a bust for Urban VIII by Giovanni Gonnelli) assuming that the sculptor’s blindness was not complete, those who believe that the high quality is due to the fact that the artist executed a copy of a similar portrait made by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (to whom it actually bears a close resemblance), and those who preferred to anticipate the dating, since we know for certain of two portraits of Urban VIII made by Giovanni Gonnelli, one of which is preserved in the Vallicelliana Library in Rome: the latter may be the bust to which the payments refer, while the one in Palazzo Barberini may instead belong to an earlier period.

|

| Giovanni Gonnelli known as il Cieco di Gambassi, Portrait of Urban VIII (1637?; terracotta; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini) |

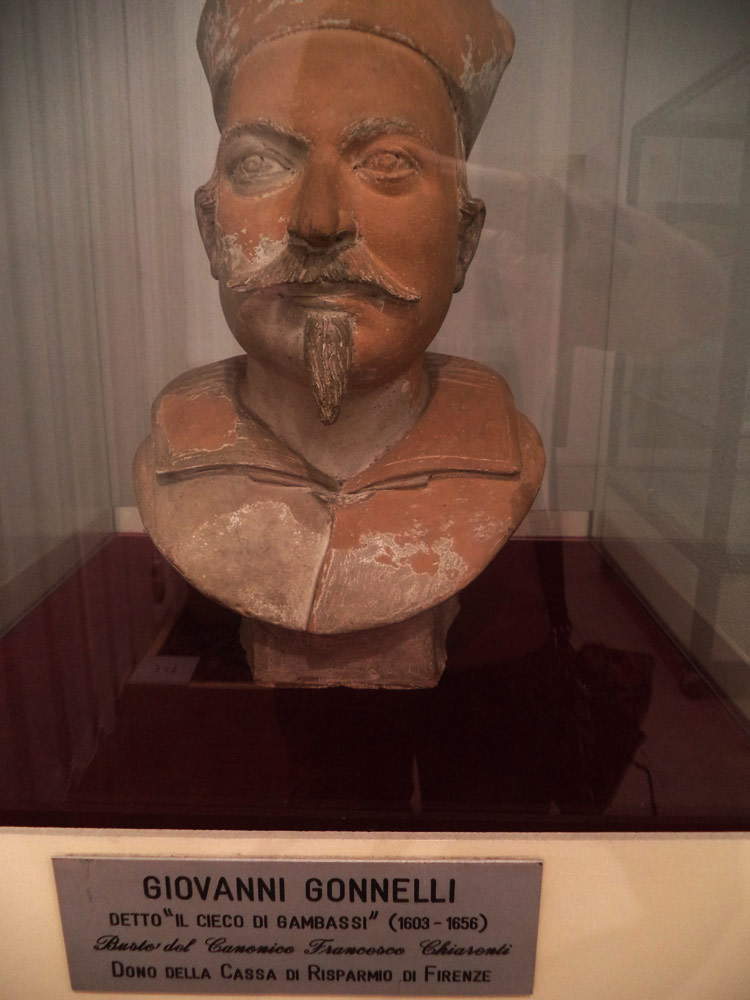

The latter hypothesis is the one given credence by a distinguished scholar, Maria Grazia Ciardi Duprè dal Poggetto, who is credited with having been the first to publish the bust that the public can now admire at the Museo del Vetro in Gambassi Terme. It is a work bought in 1983 by the Municipality of Gambassi Terme, which clearly did not want to miss a testimony of its most illustrious citizen, and therefore decided to proceed with the purchase of the sculpture, at the time owned by an antiquarian from San Gimignano, Paolo Pedani, who declared that he had received it as an inheritance from his maternal grandmother. This statement is consistent with the family history of the subject depicted, canon Francesco Chiarenti: his name is inscribed in Latin on the base of the bust (“Franciscus Clarentus canonicus 1640”: 1640 is the year it was made). A descendant of his, Francesca Chiarenti, had married a Florentine magistrate from a San Gimignano family, Tommaso Cepparelli, in the early 18th century: the antiquarian’s grandmother was a Cepparelli.

This is a work signed and dated: Giovanni Gambassi Cieco made the year 1640. And the appellation “Blind” was also the same with which the artist had signed the portrait of Maffeo Barberini: since he lost his sight, the artist is in fact known to all as the Gambassi Blind. And Giovanni almost proudly uses this nickname, as if to show that he has nothing to fear in comparison with his colleagues to whom sight is not defective. Compared to the bust of Urban VIII, the qualitative gap is quite evident: the lower quality of the work is probably due to the fact that the artist, then 37 years old, had already completely lost his sight. In spite of this, his great passion for art is not diminished, allowing him to still create extraordinary portraits, which have the unbelievable when one considers that they are the product of a blind person. And it is again Filippo Baldinucci who illustrates what the method of the Gambassi Blind Man is. As a first step, he models with clay the shape of the head, whoever is the subject he has to portray, and having done this he places it on top of a board, a short distance from his model. The model should be close so that the sculptor can touch it as much as necessary, but always very gently. With the first touches, he acquires information about the height and width of the face, as well as the parts that are more or less in relief. Then, again using only and exclusively his hands (John’s touch had in fact developed astoundingly), he begins to study the lips, the cheekbones, all parts of the face, carefully and keeping well in mind everything he touches. To better fix the proportions and to ensure symmetry in the final result, the artist holds his hands together, as if to form a kind of mask to be applied to the model’s face, and then to be brought back to the clay form. And always moving from the model’s face to the clay, he continues to excavate the material and study the subject’s features, to make changes and go over the strokes, until he finds that the result is similar. The last step is the eye lights-a detail too fine to create with his hands (on a par with many others impossible to achieve with his fingers). To do this, John uses a straw, with which he impresses the surface of the clay.

The result of this method is the portrait, which is extraordinary and now preserved in the Glass Museum in Gambassi Terme. Extraordinary from a purely historical and documentary point of view, because it is one of the rare certain works of the Blind Man of Gambassi. And extraordinary because, looking at it, one almost cannot believe that it was made by a blind man. Writes Maria Grazia Ciardi Duprè dal Poggetto: “a very strong sense of life emanates from volumes delimited by blurred but essential lines: see both the front view, which testifies to its breadth, and the profile view, which allows us to assess the consistency of the third dimension - essential and aggressive - of the features, the goatee, the mustache, the outstretched and inanimate collar [...].” A portrait endowed with an “absolute and almost metaphysical simplification,” which reveals a strong “awareness of the new stylistic values that can be brought about by blindness.” The lines are simple, the light effects resulting from the solids and voids that characterized the portrait of Urban VIII are missing, the portrait gives much more the idea of impression than the one previously executed: but it is still something unique and exceptional.

|

| Giovanni Gonnelli called the Blind of Gambassi, Portrait of Francesco Chiarenti (1640; terracotta, 48.2 x 27.5 x 26.5 cm; Gambassi Terme, Glass Museum). Ph. Credit |

|

| Giovanni Gonnelli known as the Blind Man of Gambassi, Portrait of Francesco Chiarenti, front view. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Livio Mehus, Portrait of Giovanni Gonnelli known as the Blind Man of Gambassi (c. 1655; oil on canvas, 200 x 135 cm; Florence, Gerini Collection) |

Today, that of Giovanni Gonnelli known as the Blind Man of Gambassi is a figure little known to most. No exhibitions have ever been dedicated to him, nor is there a complete monographic survey of his work. The number of works referable to his hand is exeiguous: these are mainly busts (including two portraits of Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici), and some sacred works scattered in churches in Tuscany. These are all sculptures characterized by those simple, essential lines that characterize the bust of Francesco Chiarenti preserved at the Glass Museum in the artist’s hometown. But despite his little notoriety, anyone who knows him does not easily forget his story. For it is the story of a painter who “deprived in all respects of the light of the eyes, in sole force of imagination itself, joined to an exquisite perfection had by nature in the sense of touching, made to see in his work in the same time two marvels, the work without light and ’l condurre colla mano cose worthy of much praise.”

Reference Bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.