by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 12/04/2018

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

The Etruscans were a people who loved sports (although they preferred to watch them rather than play them): here are what their favorite sports were and where we find them depicted.

Boxing, running, long jumping, wrestling, discus throwing, javelin throwing, horse racing-these are just some of the sports we practice today, but they were already practiced by the Etruscans more than two and five thousand years ago. We know that among the Etruscan civilization the use of sports was already widespread, but it should also be emphasized that our knowledge about Etruscan sports is much more limited than what we have about Greek or Roman civilization, mainly for one reason: there are very few written records of the Etruscans, and as far as works of art are concerned, the picture is certainly fragmentary since, on the basis of what has come down to us, it is possible to assert that the Etruscans accorded a greater predilection to the time of competition than to that of training. Etruscan artistic productions (especially ceramics and frescoes) abound with scenes of boxing (which we can imagine, using a modern locution, as the “Etruscan national sport,” given the high number of depictions of boxers that have come down to us), chariot races, and wrestling matches. And the depictions are so precise that scholars (above all Jean-Paul Thuillier, an undisputed authority in the field of Etruscan sports) have even gone so far as to outline many of the technical aspects of sports practice in Etruria.

Before taking a closer look at what the Etruscans’ favorite sports were, how they practiced them, and what their rules were, it is necessary to outline how the Etruscan civilization viewed sports practice. A first difference that distinguished the Etruscans from the Greeks consisted in the fact that, for the Etruscans, the practice of sports was not considered fundamental to the development of the person (when, on the other hand, the culture of physical fitness was a basic tenet of Greek civilization): athleticism, for the Etruscans, was never a value, which is why depictions of figures intent on exercising are so rare. If the culture of physical fitness is a founding trait of a civilization, it is quite normal to find it represented in works of art, which is why Greek art abounds with examples in this regard. Conversely, if sports represent more of a spectacle and entertainment than a daily exercise to which the citizen should devote himself, it follows that training remains reserved for a small circle of people (in whom art is not interested), and artistic productions end up preferring other aspects of sports practice. Another important difference between Greeks and Etruscans consisted in the social status of the athletes: free men in Greece, due to the fact that sport was held in the highest esteem, slaves in Etruria. They were, however, slaves who were “well fed and well treated,” as Thuillier points out, and totally devoted to the practice of sports: we can therefore imagine that they enjoyed far better living conditions than slaves who were delegated to other tasks. It could, however, have happened that, for pleasure, nobles also engaged in sports.

A further and important difference is the very conception of sport among the Greeks and Etruscans. Of course: to simplify, we use the modern term “sport,” but this is a stretch, because it would be more correct to speak of agon (for the Greeks) and ludus (for the Etruscans and later for the Romans: ludus is in fact a Latin term). Theagón of the Greeks is a real competition (agonistic, we would say: the adjective derives precisely from agón), much felt by the athletes. Ludus, on the other hand, is spectacle (the term could be translated as “play”), where the athlete is called upon primarily to entertain the audience. To use a modern comparison, and of course making the proper proportions, it would be as if the Greeks had preferred Olympic wrestling, and the Etruscans wrestling. Obviously then even the ludi had their own ceremonies and their own solemnity (somewhat like in wrestling, where world champion titles were awarded), but the main purpose was always and still the spectacle. In short: we could say that the Etruscans loved to watch sports rather than to practice them.... !

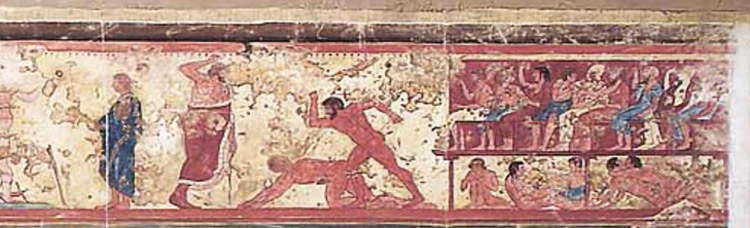

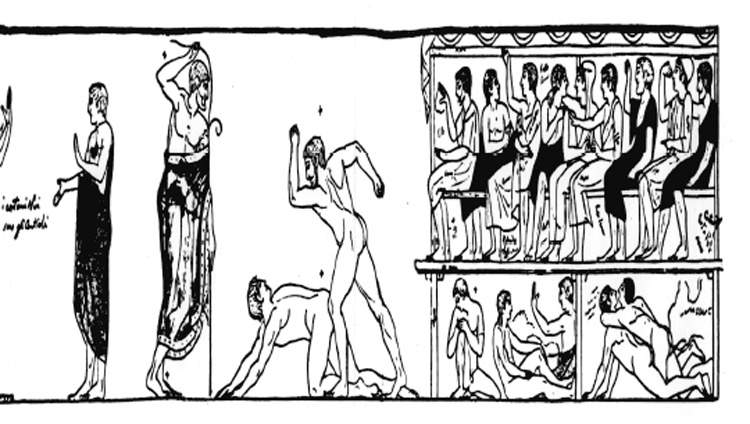

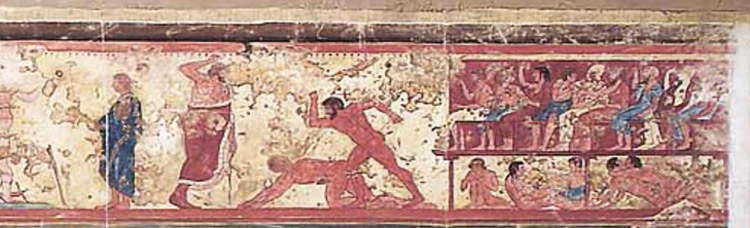

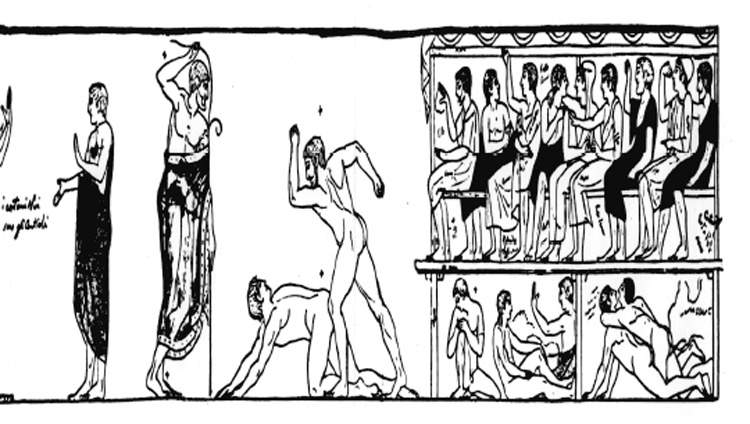

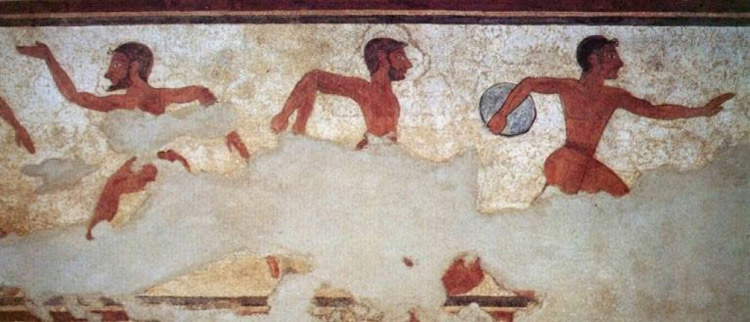

Another important aspect to emphasize, regarding Etruscan sport, is the public dimension of the events. Indeed, in several representations of races and competitions found in Etruscan art it is possible to see depicted an audience watching the event. Of course, it was not uncommon for members of the upper classes of the population to hold sporting competitions for a small audience, perhaps as entertainment during a banquet (for example, in the terracotta slabs from Murlo, tiles that decorated the facade of a dwelling, we see a horse race and a banquet scene, and similar associations are not uncommon in Etruscan art), but the games often took on a collective dimension as well. In the frescoes of the Tomb of the Bigas in Tarquinia, for example, stands, made of wood, are clearly distinguishable (and it should be noted that today some architectural firms are returning to consider wood as precisely the construction material for grandstands in stadiums, even large ones). Above these bleachers, which, moreover, are covered, sit spectators, both men and women, who watch certain sports competitions. It is, in this sense, the most valuable document that Etruscan art has left us, since in no other surviving work is it possible to find stands of this kind. The characters themselves are very interesting: in one of the tribunes we also see a woman who, in a very affectionate gesture, embraces her man by placing her arm around his neck and smiling toward him. A gesture that, Thuillier says, almost represents a confirmation about the equality between men and women in Etruscan society, since, in this scene, it is the woman who “takes the initiative with a very modern gesture.”

|

| Etruscan art, Slab with banquet scene (6th century B.C.; terracotta; Murlo, Antiquarium of Poggio Civitate - Archaeological Museum) |

|

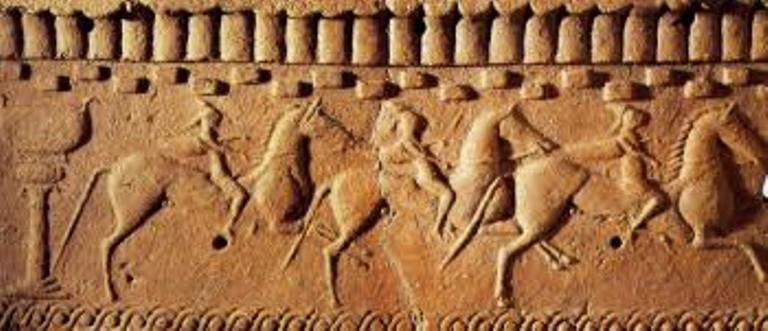

| Etruscan art, Slab with horse racing scene (6th century BC; terracotta; Murlo, Antiquarium of Poggio Civitate - Archaeological Museum) |

|

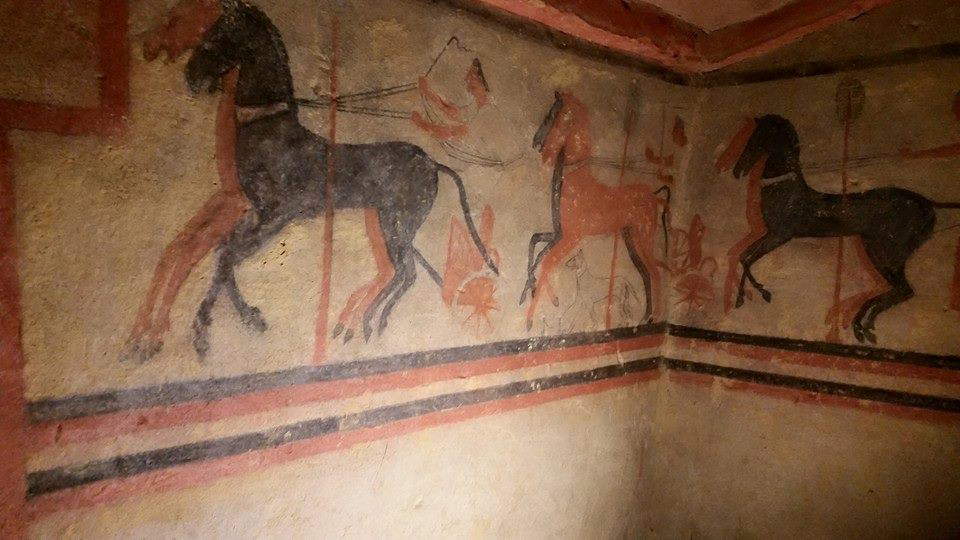

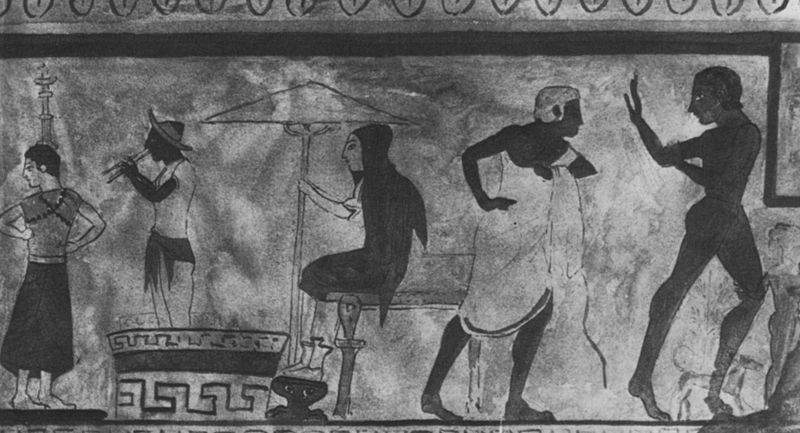

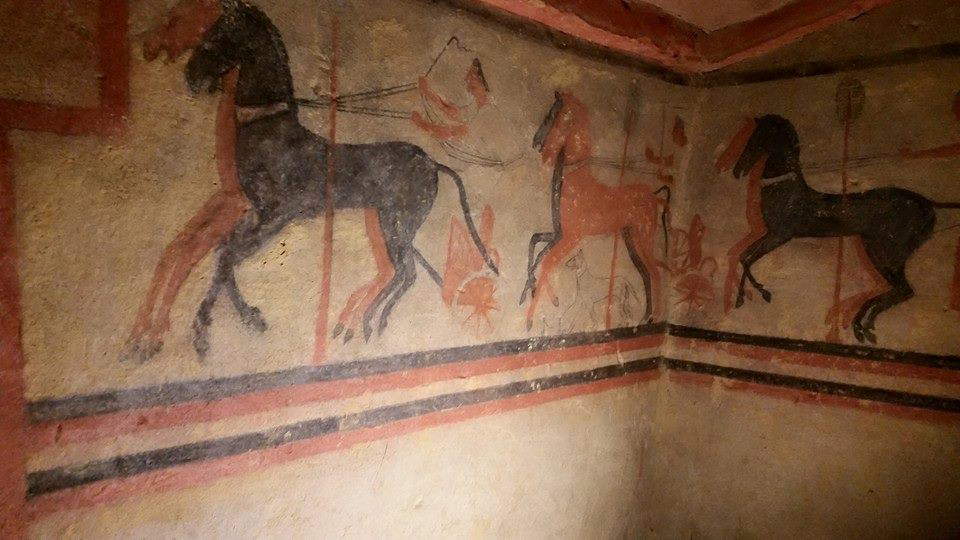

| Etruscan art, Scene of chariot racing (second quarter of 5th century BC; fresco; Chiusi, Tomb of the Hill) |

|

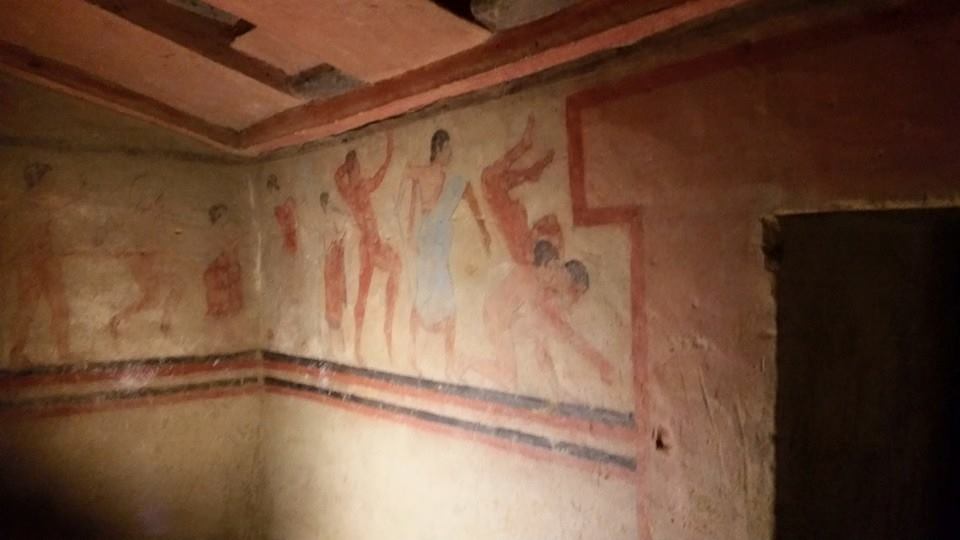

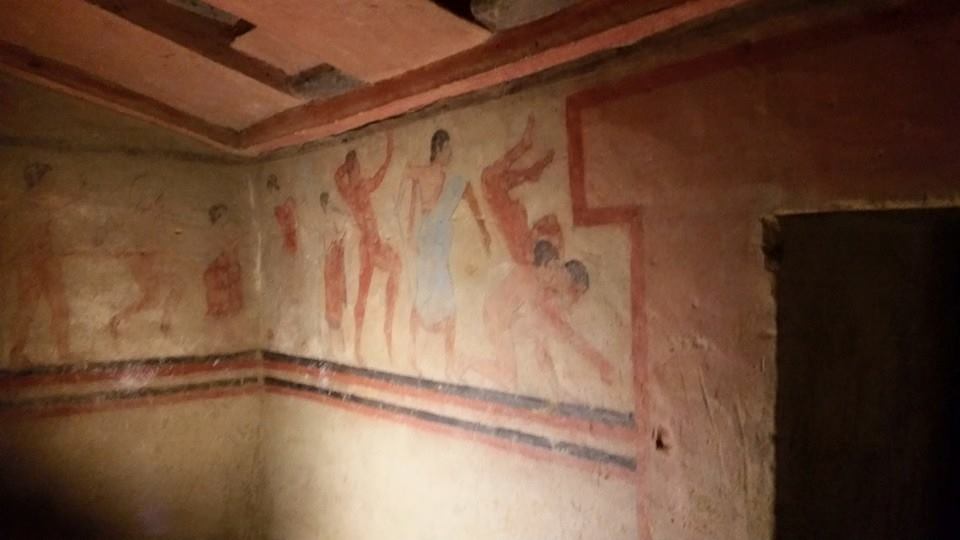

| Etruscan art, Fighting scene (second quarter of 5th century B.C.; fresco; Chiusi, Tomb of the Hill) |

|

| Reproduction of the left wall of the Tomb of the Bigas at Tarquinia (1901; oil on canvas, 204 x 516 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Reproduction of the left wall of the Tomb of the Bigas of Tarquinia, detail with the stands |

|

| Tomb of the Bigas of Tarquinia, cast by Otto Magnus von Stackelberg (1827), detail |

|

| The wooden grandstands of the new stadium of Puskás Akadémia FC (Hungarian premier league soccer team), opened in 2014 |

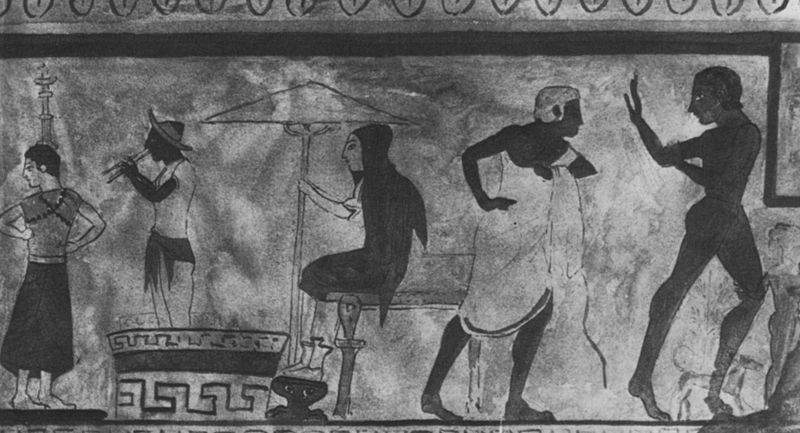

So, sports competitions were not only held indoors in aristocratic circles, but in some cases were also open to the public. And there were several reasons why games and competitions were held. Among the most widespread practices was the playing of games as part of a funeral ceremony: the athletes, in essence, honored the deceased with their competitions. This is what we see, for example, in the Tomb of the Monkey, where the deceased, a woman, is portrayed seated and veiled as she watches the competitions taking place around her. Sports games could then be organized in honor of the gods: in Herodotus’s Historiae, for example, we read that following the Battle of the Sardinian Sea, a naval conflict that was fought in the sea near the mouths of Bonifacio and saw on the one side an army of Greeks from Phocaea, who had fled to Corsica to escape the persecutions of Cyrus the Great, and on the other a coalition of Etruscans and Carthaginians, the Ceretani (i.e., the Etruscans of Cerveteri), after the outbreak of a plague caused by the Phocaean prisoners, sent a delegation to Delphi to question the oracle about what to do. The oracle responded by arguing that the Ceretans should organize games in honor of the dead. That of public games was, after all, a common practice in sixth- and fifth-century B.C.E. Etruria, as is also confirmed by Livy in his work Ab urbe condita, who informs us of a further case of sporting competitions, those organized to celebrate a particular event. In particular, Livy relates that King Tarquinius Priscus wanted to celebrate with ludi a victory in battle over the Latins.

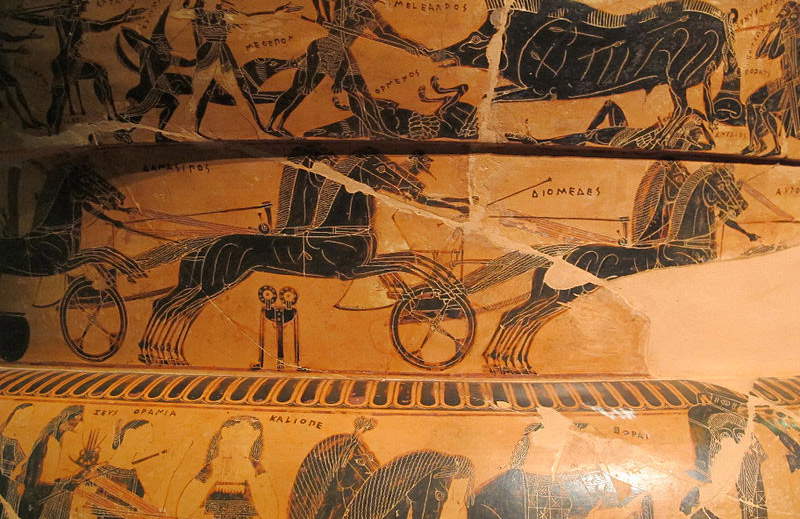

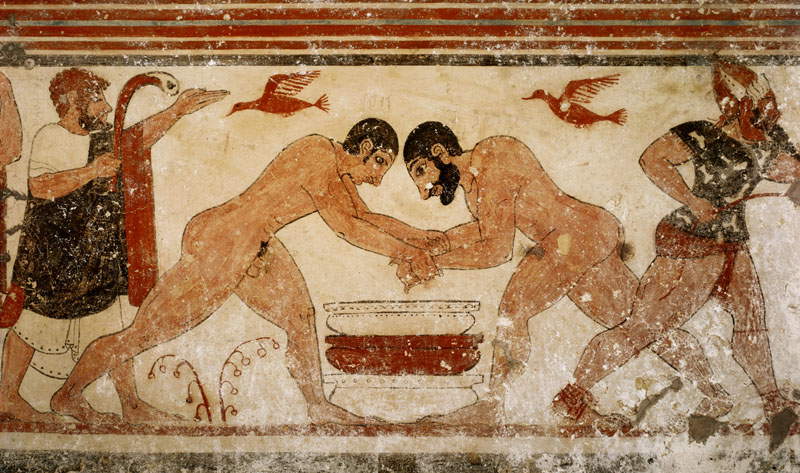

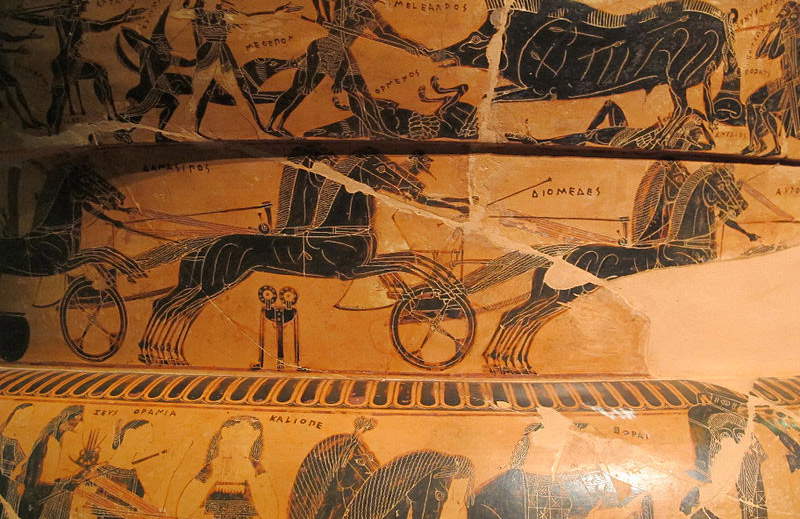

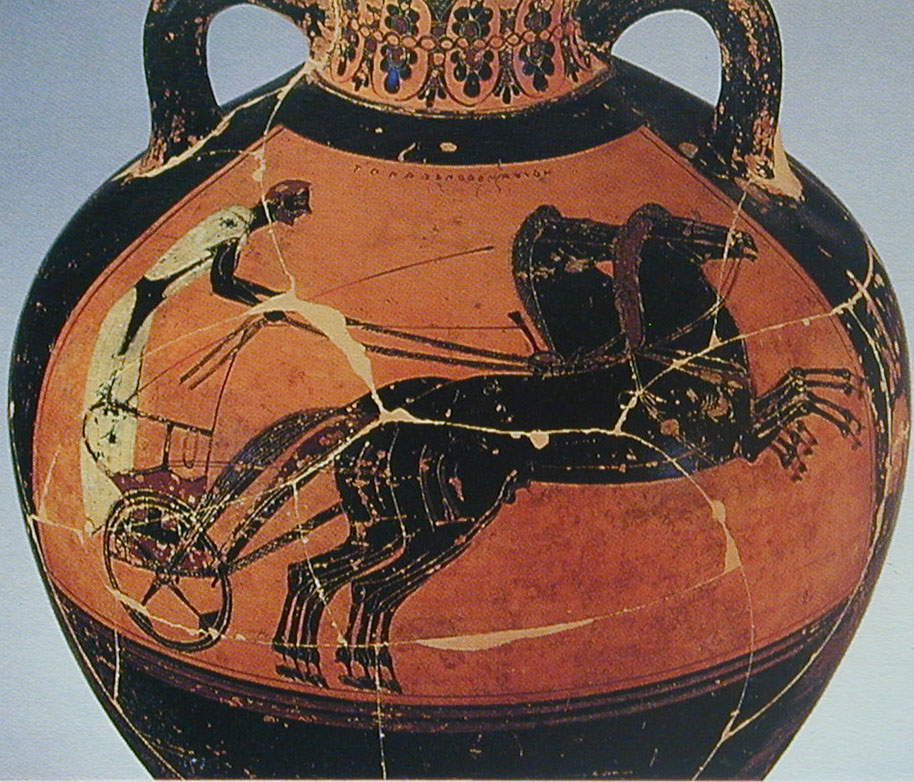

As in modern sports competitions, the Etruscans also had a custom of rewarding winners with substantial rewards. And the reward was much more modern than one might imagine: if today those who win a sports competition are rewarded with a cup (i.e., an object that, although today it retains only a purely symbolic function, was originally used to drink and thus to toast success), at the Etruscans they obtained as a prize a tripod, an object that served to support a basin or container for libations, and that could also be of great artistic value. In Etruscan art, there are several representations of tripods against the background of boxing matches, horse races or, in general, sports competitions. It can be seen very well, for example, in the very famous François Vase, an extraordinary find currently preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. It is a large crater (i.e., a vase in which, during banquets, water and wine were mixed to be served to diners) from the sixth century, of Attic production but imported to Etruria (exchanges between Greece and Italy were frequent at the time, and the Etruscans were strong importers of ceramics: there was a special production for the Etruscan market in Greece), which owes the name by which it is known to its discoverer, the archaeologist Alessandro François (Florence, 1796 - 1857). In one of the many scenes that populate it we see just such a horse race with, in the background, a tripod waiting for the winner. Even closer to modern cups, however, is the prize we can see in the already mentioned Murlo terracottas. Here, we still have a horse race (which are no longer driven in a chariot, but are mounted by jockeys), and on the left we can see a large vessel placed on a column: a kind of ancient cup reserved for the champion. And, who knows, perhaps prizes were also provided for the first three finishers, exactly as it happens today: in the Tomb of the Àuguri, in Tarquinia, two wrestlers can be seen facing each other, and behind them it is possible to make out three large vase-like cups of different colors, stacked on top of each other.

|

| Etruscan art, Scenes of funeral games and in the center portrait of the deceased (c. 480 BCE; fresco; Chiusi, Tomb of the Monkey) |

|

| Ergotimos and Kleitias, Attic krater known as François Vase (c. 570 BC; black-figure pottery, 66 x 57 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Vaso François, detail of horse race with, in the background, the tripod for the winner |

|

| Etruscan art, fight scene (540-530 BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Àuguri) |

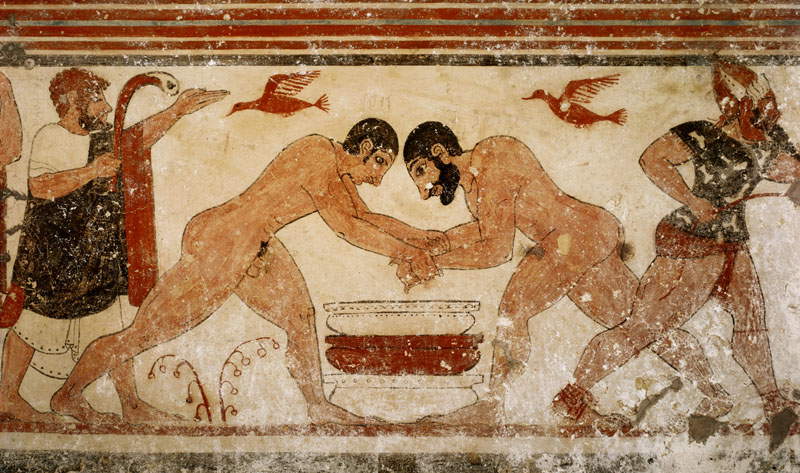

The very Tomb of the Augurs presents us with one of the most interesting depictions of sporting encounters to be found in Etruscan art. It is a fight scene: and in these wrestlers, “all expression,” wrote the archaeologists Giovanni Becatti and Filippo Magi in 1955, “is concentrated in the heavy muscular bodies, while the fixed and attorned heads seem without thought, and with fine sensibility the painter has made the hair shaved without any ornament of curls, forming a continuous line of outline that uninterruptedly continues that of the profile of the face and neck, avoiding any detail that might break this unity and hold and divert the gaze of the full-bodied mass of nudes. Shaven, unkempt heads of wrestlers of trades, both of an atonal brutality, which make a significant contrast with those of the judges of the competition.” The two scholars pointed out that the muscular mass of the two athletes, much more developed than that of the judges and, alongside, the character engaged in the typically Etruscan game of phersu (which will be discussed in a moment), suggests that they are two professional athletes. However, professional sportsmen, in Etruria, were always people of low social status, who did not enjoy freedom: nobles, as mentioned above, could dabble in recreational and sporting activities, but never at the professional level (although scholars have long argued that nobles could nevertheless take part in competitions in official contexts). As for the aforementioned phersu, a very violent game, probably the bloodiest in the Etruscan world, we find it depicted in many frescoes, but we have very little knowledge of it. As mentioned, it was typically Etruscan: in this game, the protagonist (who was called phersu), a character wearing a mask (in Latin, the term for mask is persona), perhaps an actor, held a leash on a ferocious dog, aiming it at a character whose head was covered by a white sack. In many depictions, this character bears conspicuous wounds inflicted by the beast: however, we do not know whether the game ended with the death of the contender (and thus whether the condemned were subjected to it), or whether it was simply a truculent spectacle that, however, did not involve too heavy consequences for the player. Scholars, however, have wanted to see in phersu an antecedent of the gladiatorial games of ancient Rome.

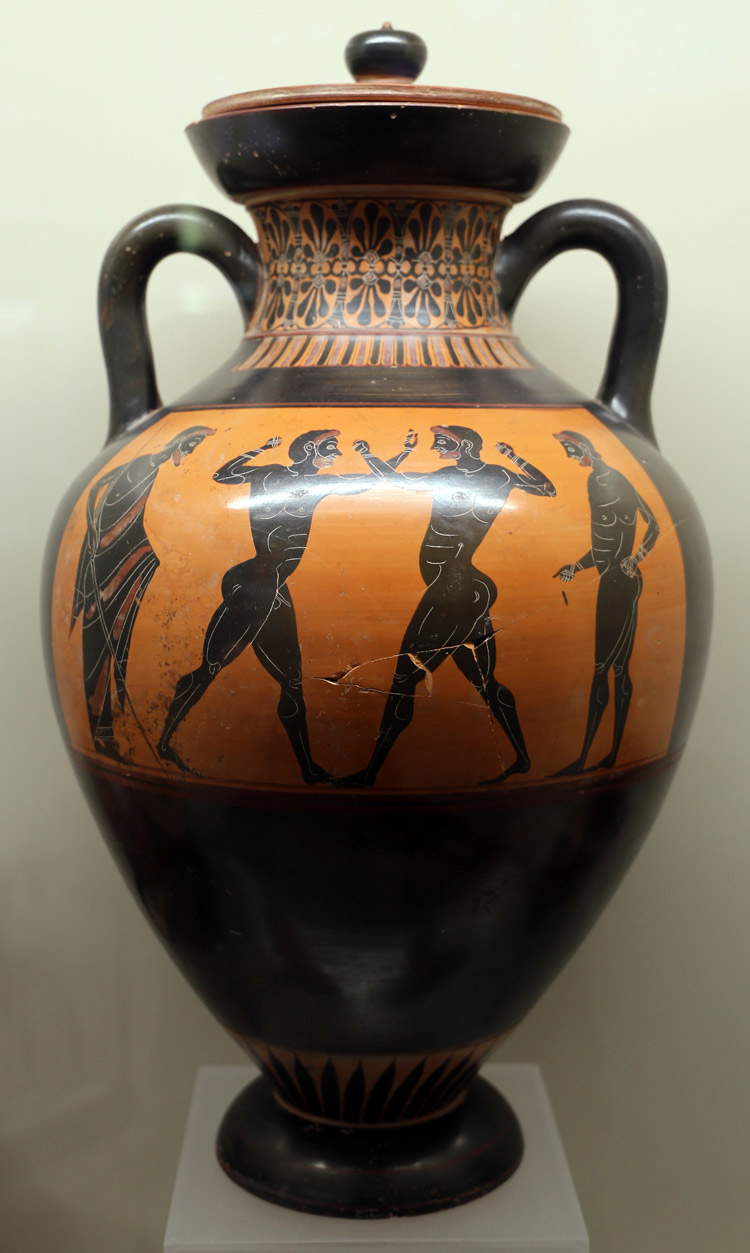

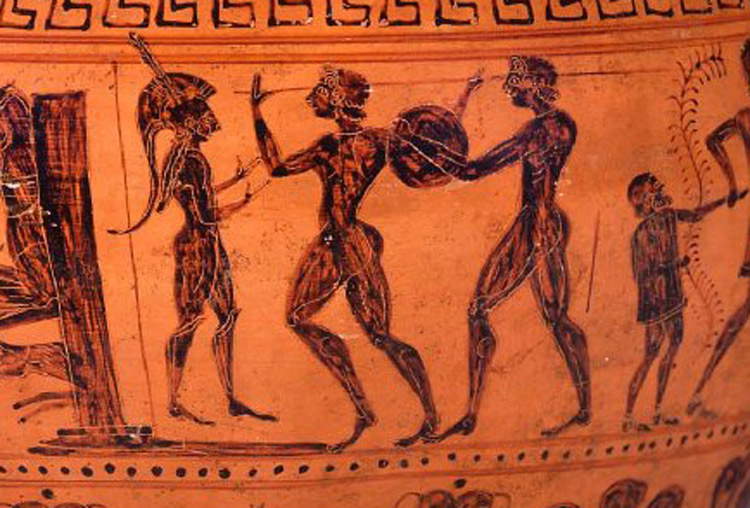

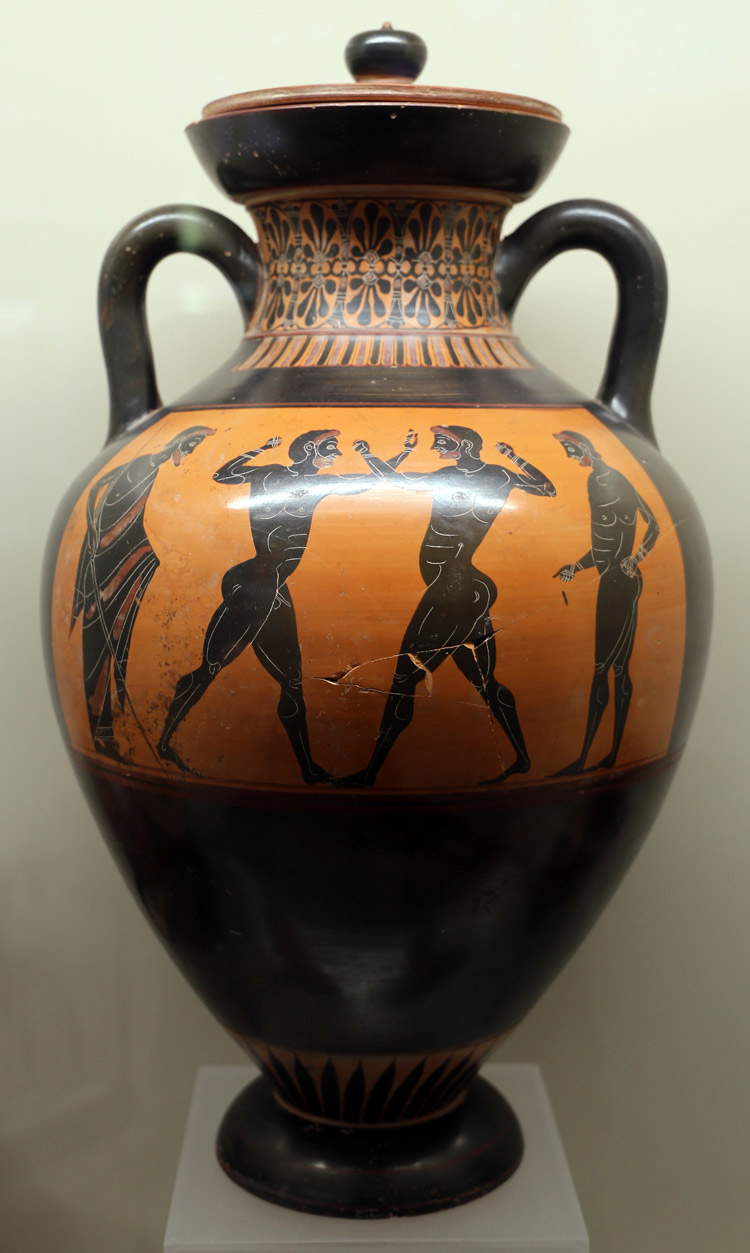

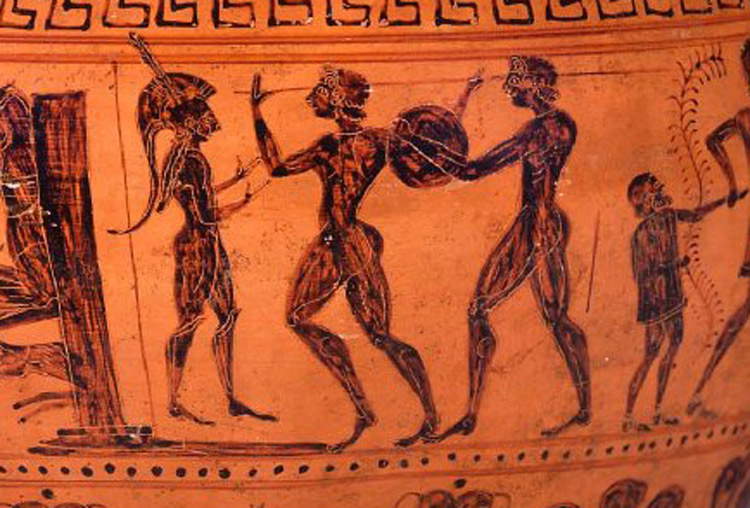

But what were the most popular sports played by the Etruscans? We could start with what, as mentioned, was the most popular: boxing. We see a scene with two boxers facing each other on the decoration of an Attic-made amphora, found in the Tomb of the Warrior at Lanuvio and now in the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome. The work presents a scheme typical of the depiction of boxing matches: the two athletes face each other with their fists raised, facing each other, and with the judges observing them (in the case of the Lanuvian amphora, only the prize that usually appeared in the background is missing). Characteristic of ancient boxing is precisely this strange guard position, with the fists held very high, protecting the face, much more so than in modern boxing: it is therefore conceivable that, in the boxing of the Etruscans, only blows brought to the face were allowed. This rule would also seem to be confirmed by written sources (for example, by Virgil, who in the fifth book of theAeneid speaks precisely of boxers striking each other in the head), and is probably due to the fact that, in order to achieve victory, blows to the face were considered more effective (not to mention the fact that these are much more spectacular blows than those brought to the body, and it has been mentioned how the Etruscans loved the entertainment aspect more than the competition aspect). Moreover, in ancient boxing, both in Greece and Etruria, weight categories may not have existed: in a Greek inscription found in Francavilla Marittima, an athlete boasts of having won a boxing competition by defeating athletes far more physically gifted than himself.

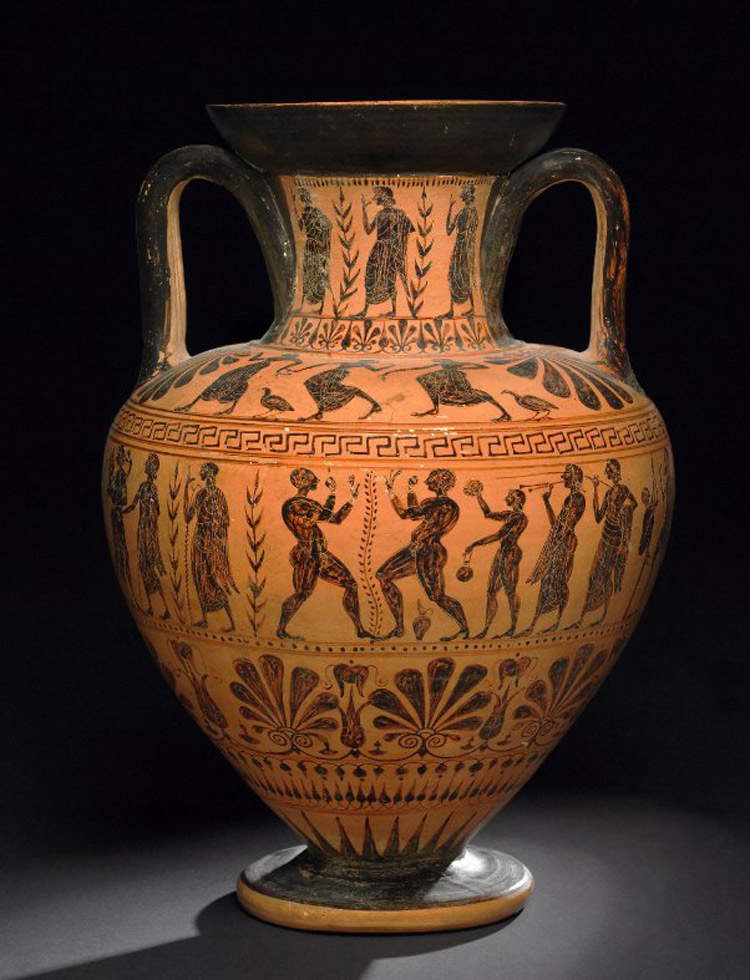

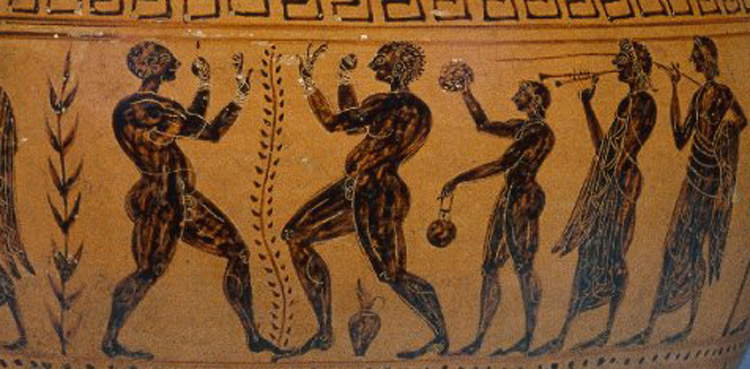

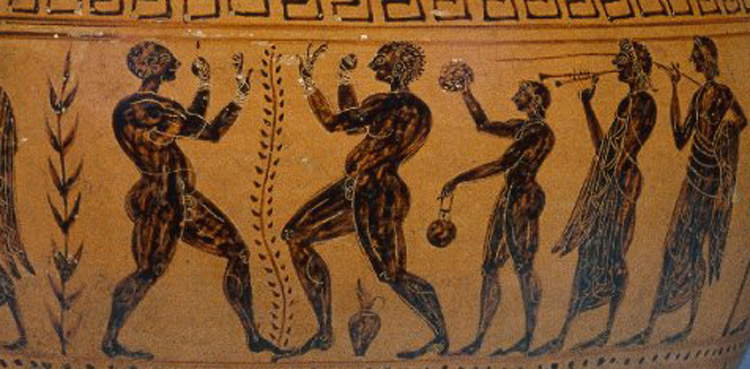

A uniquefeature of Etruscan boxing, however, was the musical accompaniment: in fact, boxers often appear together with a musician intent on playing the tibia, the characteristic double flute. We do not know, however, what the exact role of theauleta, or player, was: some have speculated that the music was used to guide the boxers’ moves, in which case Etruscan boxing would have been a bit like modern Brazilian capoeira, a mixture of dance and martial art. Some, on the other hand, think that it was merely an accompaniment, but without any practical purpose for the contention. Those, on the other hand, who believe that it did have practical purposes think that the music probably served to punctuate the moments of the match, and to bring order to the contest by giving rhythm to the boxers’ actions. Still, another hypothesis has it that the auleta served only to kick off the bout or, conversely, to end it (somewhat as is the case in modern boxing where it is the gong that marks the sequence of rounds). And if we were to think that boxing matches in Etruria were divided into rounds exactly as they are today (although there are no footholds in the ancient texts that can assure us of this), the auleta would have been a bit like modern cheerleaders and would have simply entertained the audience between one round and the next. Difficult, however, to find a solution.

|

| Antimenes painter, Panathenaic amphora with boxing scema, from the Tomb of the Warrior in the Osteria necropolis (530-510 BC; black-figure pottery; Rome, National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan Art, Amphora known as Amphora B64 (c. 510-500 BC; black-figure pottery, 45.72 x 31 cm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Etruscan Art, Amphora known as Amphora B64, detail with boxing scene |

|

| Capoeira match with players. Ph. Credit Ricardo André Frantz |

|

| Etruscan art, phersu scene (540-530 BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Àuguri) |

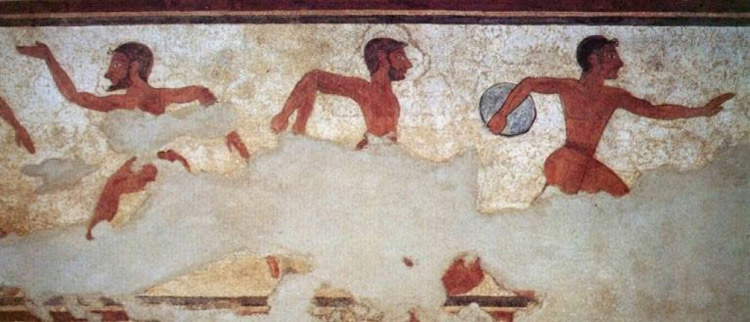

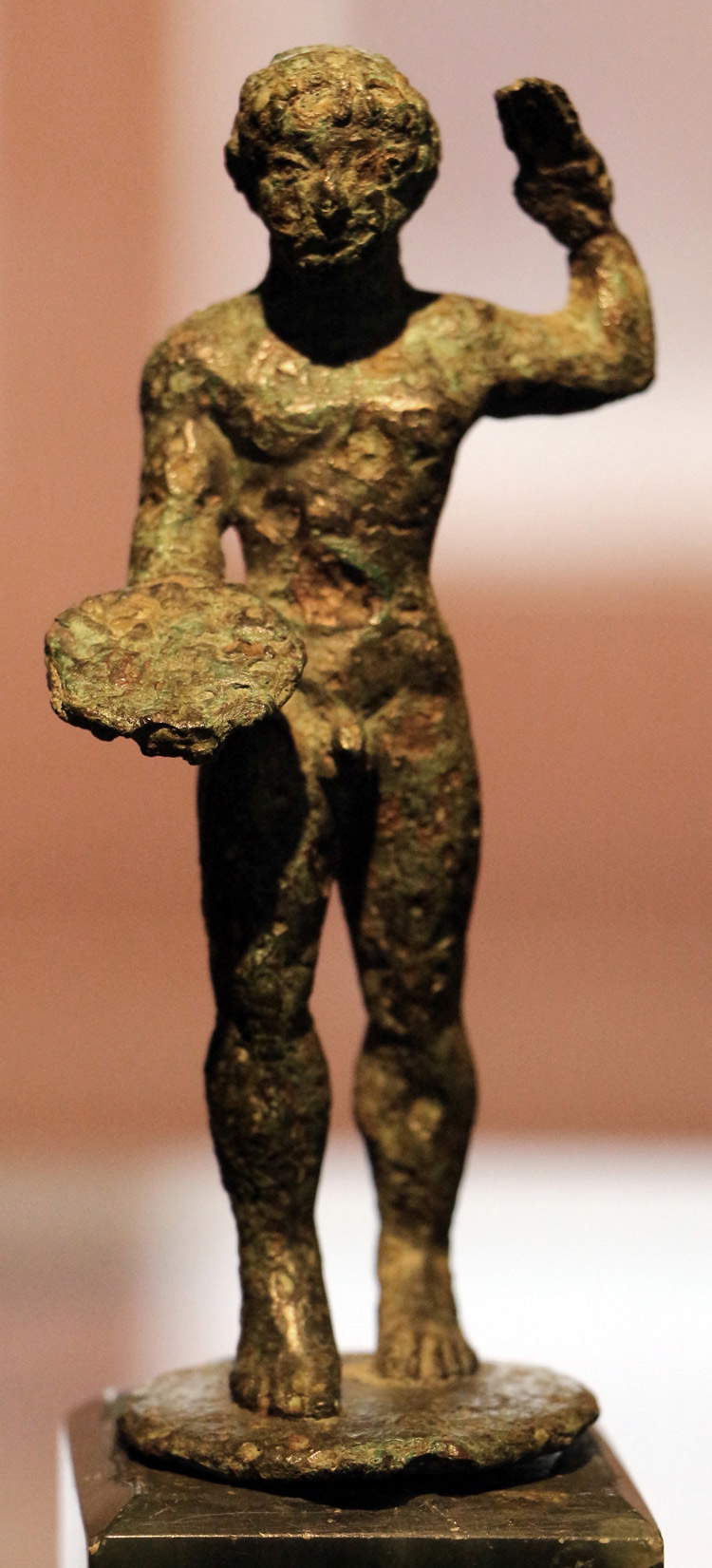

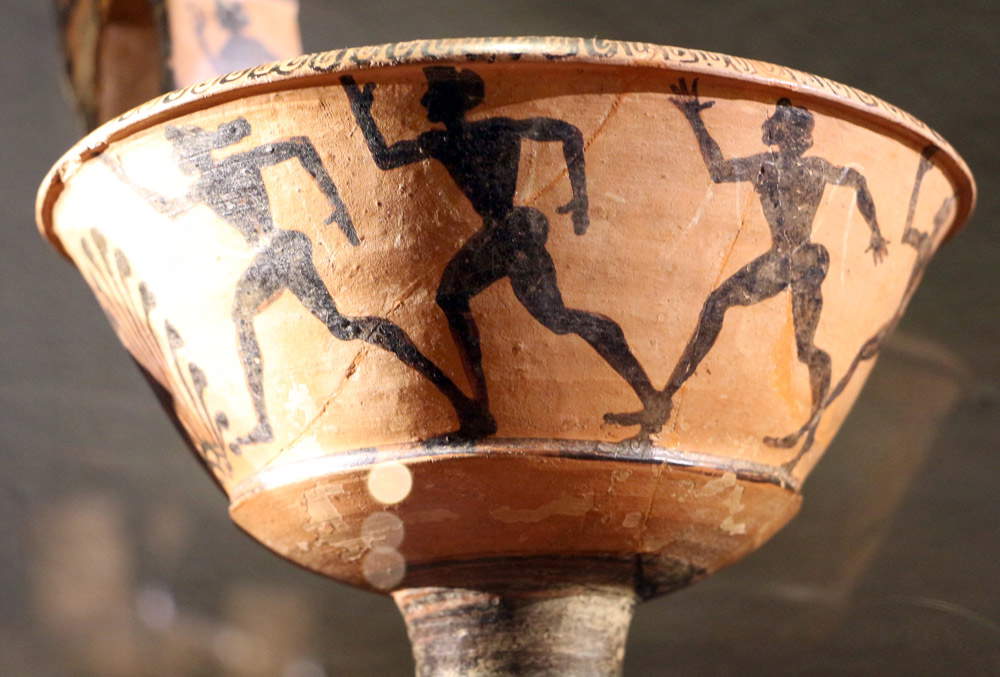

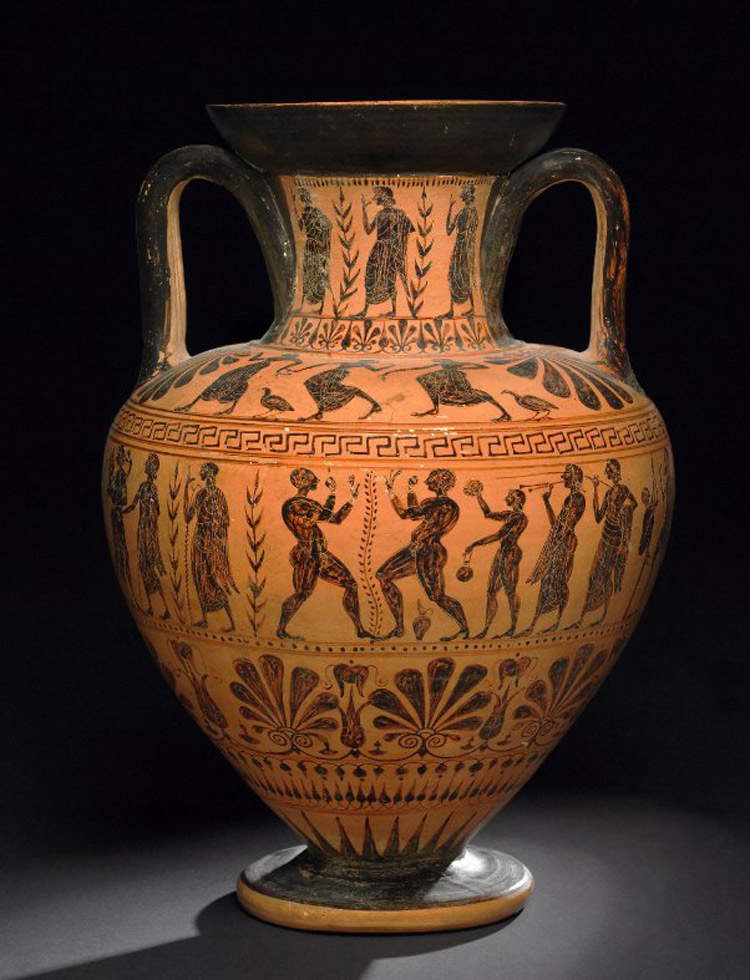

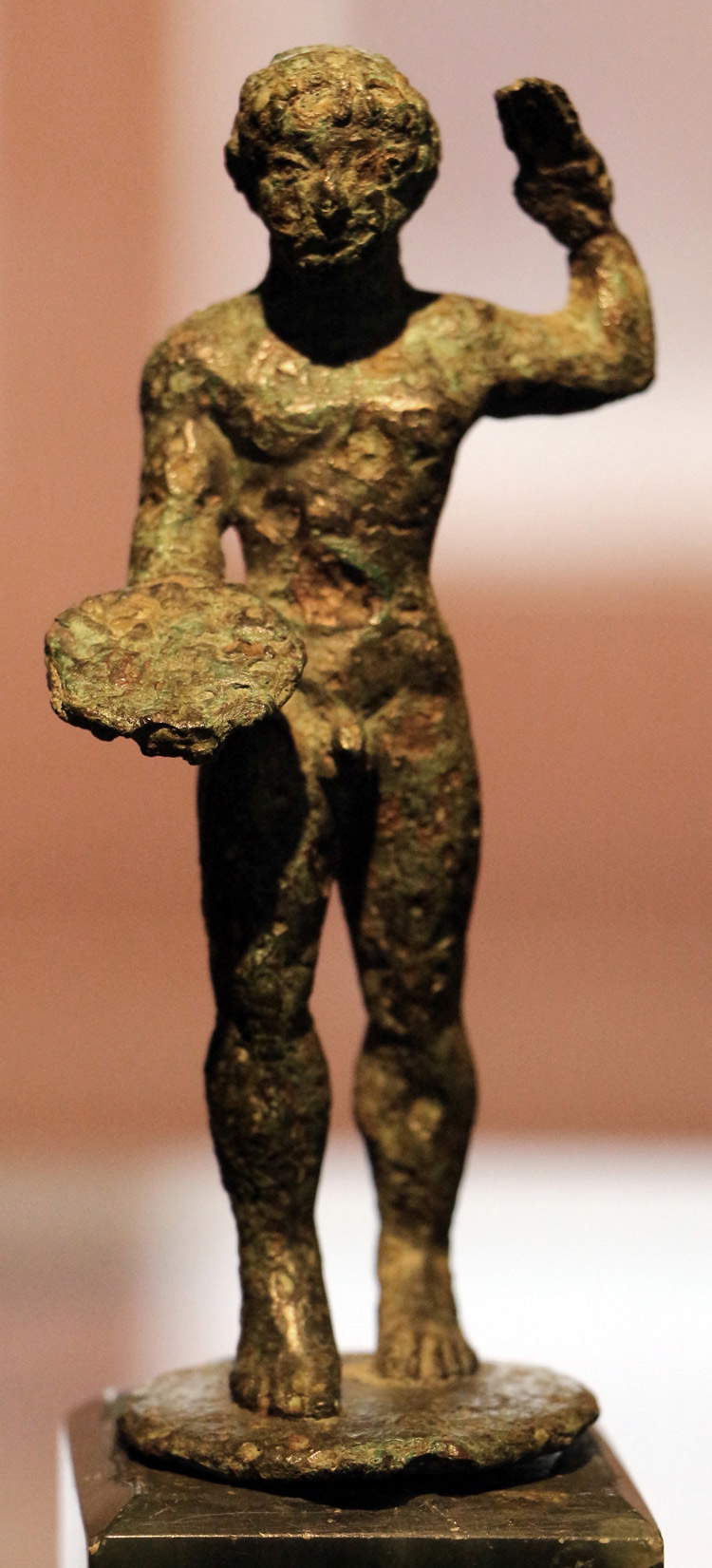

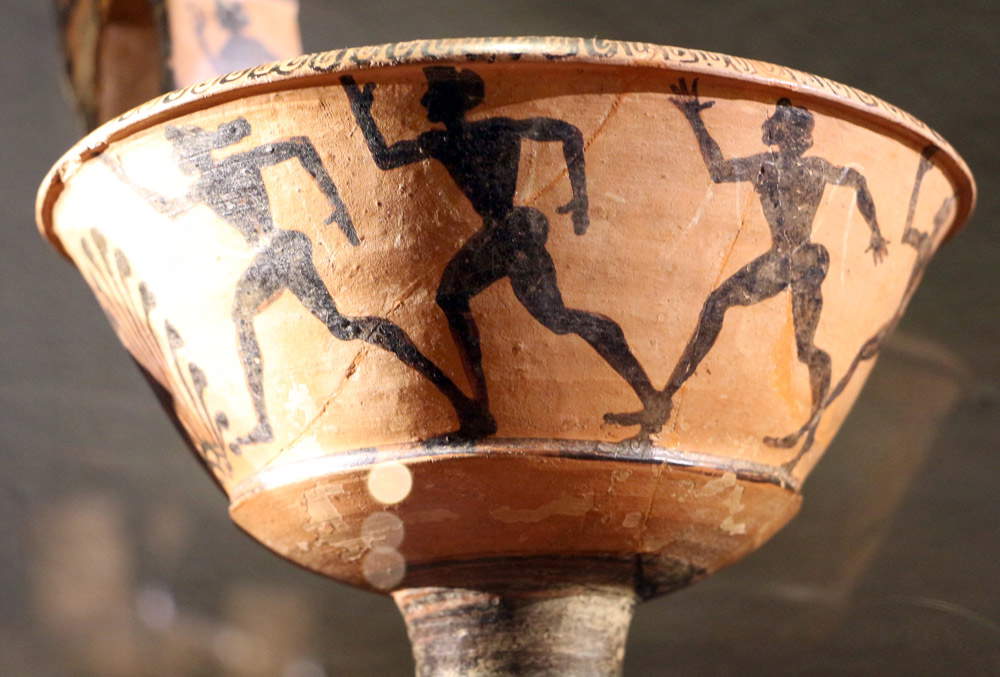

Many others, however, were the sports practiced by the Etruscans. Particularly prized was wrestling (we see it depicted in the very Tomb of the Àuguri, in the illustration above): the purpose of the game, in its ancient forms, was to make the opponent lose his balance and fall to the ground (with the difference that, unlike modern wrestling, for the ancients the bout was concluded when one of the two contenders fell: wrestling on the ground was not contemplated as it is today). To this end, it was customary for athletes to anoint themselves with oil, not only to prepare their muscles, but also to make their opponent’s grappling more difficult: many Etruscan museums display specimens of strigil, a tool that was used to remove the oil from the skin once the contest was over. The Etruscans then practiced all the other four sports of the Greek pentathlon (the fifth being wrestling itself): the long jump, discus throw, javelin throw, and running. The long jump was the only type of jump practiced in antiquity (the high jump was not covered) and could be conducted with or without momentum, and in any case often with musical accompaniment. We find a jumper depicted, as he is landing, in the so-called Tomb of the Olympians in Tarquinia: he is depicted with his arms backwards, as he is about to hit the ground, amid a group of figures engaged in other sports (this is the reason for the name by which the tomb is known). Among these is a discus: discus throwing was in fact also a sport practiced in Etruria, and several bronze statuettes depicting athletes engaged with the discus have also been preserved here. A particularly interesting discus is the one preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Populonia: we see it with the discus placed horizontally on the right forearm, and with the left arm raised (this is the movement the athlete performs to prepare for the throw). Bronze statues of throwers (one is in the Archaeological Museum in Florence), as well as ceramics, are also left regarding javelin throwing: a famous athlete engaged with the javelin is found on amphora B64 in the British Museum, depicted next to a discus. There are also many depictions on running: famous are those from the Tomb of the Olympians, and also interesting are the runners we see on a kyathos (a vase that was used for drawing: a kind of large ladle) preserved in Grosseto, at the Archaeological and Art Museum of the Maremma. The interesting fact about running is the fact that the ancients probably competed in sprint competitions, given the always muscular build of the runners we find in Etruscan art. But it could simply be an aesthetic expedient, since sprinting, in which the athlete’s athletic prowess and physical strength count more than endurance, is artistically more interesting than a cross-country race: therefore, it is quite legitimate to imagine that the Etruscans also competed over long distances, but that in works of art they preferred to represent short races.

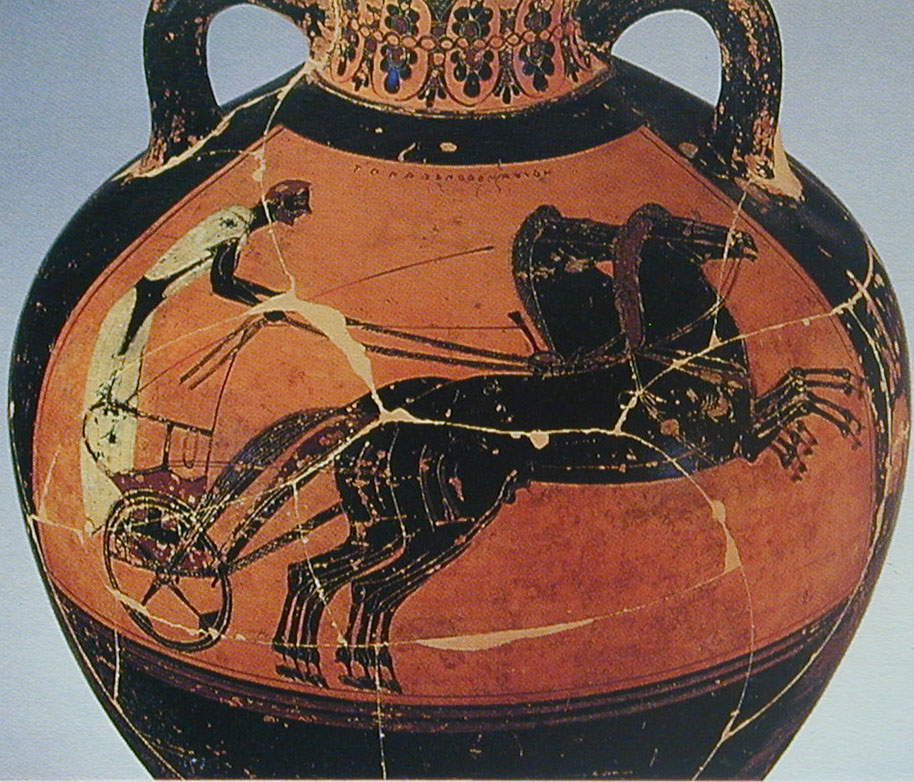

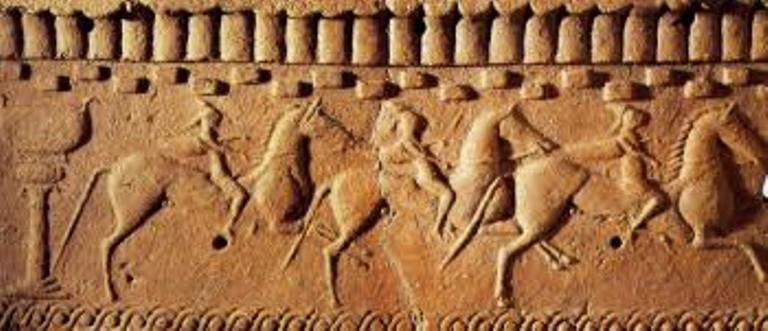

As for horse races, as anticipated, in Etruria there were both races with horses mounted by jockeys and chariot races. These were very popular sports, and proof of this are the varied depictions we find on frescoes, ceramics, and reliefs. In the Murlo slabs, for example, we have a race with mounted horses, while chariot races (especially chariots driven by two or three horses) are found in the frescoes of the Tomb of the Chariots, in those of the Tomb of the Hill, on the famous amphora in the Archaeological Museum in Florence (of Greek production, but found in Orvieto in the tomb of an Etruscan aristocrat). It was a sport particularly beloved by the nobility, who often used to hold horse races.

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Strigil (3rd-2nd century BC; iron; Cortona, Museum of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona) |

|

| Etruscan art, Runner, long jumper and discobolus (late 6th century BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Olympians) |

|

| Etruscan Art, Discobolus, candelabra cimasa (510-490 BC; bronze; Populonia, Archaeological Museum of the Territory) |

|

| Etruscan Art, Vase with running athletes (c. 510-490 BC; bronze; Grosseto, Museo Archeologico e d’Arte della Maremma). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan art, Amphora known as Amphora B64, detail with javelin thrower |

|

| Greek painter, Panathenaic amphora with charioteer (c. 565-535 BC; pottery; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

Finally, a question is in order: did the Etruscans have champions they honored? Was there, in ancient Etruria, any counterpart to today’s Roger Federer or Leo Messi? The evidence that has come down to us is really scarce to answer that question, but we do have a name, however: it is Ratumenna, a charioteer (i.e., chariot driver) from Veio, one of the most important Etruscan cities. According to legend, Ratumenna, during a race, allegedly lost control of his chariot and was thrown out of it so violently that he lost his life. The episode took place in Rome, near the gate (Porta Ratumenna, or Porta Ratumena, according to the Latin variant) that later took its name from him, and which no longer exists today: it stood near where the Vittoriano stands today. Given the popularity of the legend, and given the fact that one of the ancient gates of Rome was dedicated to him, it is entirely safe to imagine that Ratumenna was a great champion of chariot racing. And who knows, one might not imagine that Ratumenna represented then to the Etruscans what a champion like Ayrton Senna represents today to Formula One fans.

Reference bibliography

- Giovannangelo Camporeale, The Etruscans. History and Civilization, UTET, 2015 (fourth edition)

- Thomas F. Scanlon, Sport in the Greek and Roman Worlds: Greek Athletic Identities, Oxford University Press, 2013

- Nigel B. Crowther, Sport in Ancient Times, University of Oklahoma Press, 2010

- Allen Guttmann, Sports: The First Five Millennia, Massachusetts University Press, 2004

- Richard Mandell, Sports: a Cultural History, iUniverse, 1999

- Jean-Paul Thuillier, Les jeux athlétiques dans la civilisation étrusque, École Française de Rome, 1985

- Giovanni Becatti, Filippo Magi, Le pitture delle tombe degli Auguri e del Pulcinella Monumenti, Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1956

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.