by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 09/06/2018

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

The Etruscan woman was the freest in ancient societies: refined, elegant, independent, beautiful. Through Etruscan art a fascinating journey into the Etruscan female universe.

When we think of the status of women in ancient civilizations, in our imagination the figure of a woman looms large, subordinate to men, and whose task is mainly to take care of domestic activities, or at any rate to attend to typically female occupations. This was not the case, however, for the Etruscan woman: no other woman like the Etruscan woman enjoyed such a high degree of emancipation, freedom and autonomy. “Etruscan women,” has written the distinguished scholar Jean-Paul Thuillier, “knew how to be guardians of the hearth,” but at the same time they were able to “keep the crowd of servants and servants at bay. Simply, unlike Penelope and Andromache, they were not content to wait patiently at home for the return of the bride and groom, but legitimately took part in all the pleasures of life.” The high level of economic well-being of Etruscan society meant that, as early as the Archaic period (from the sixth century B.C.), the role of women had begun to undergo changes: if previously women were essentially mothers devoted to the care of the family, from this era onward they began to “leave” the domestic walls to participate more and more actively in public life. This is especially true for the area ofEtruria proper (Tuscany, upper Latium and Umbria), while in the other areas of Italy occupied by the Etruscans this process of emancipation took on decidedly slower contours: for this reason it should be emphasized that it is improper to speak of an Etruscan woman tout-court: in this article we will therefore use this locution to refer to the condition of women in Etruria between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C.E. (a period, the latter, from which, following increased contacts with the Greeks first and then with the Romans, there will be a regression in the social condition of women).

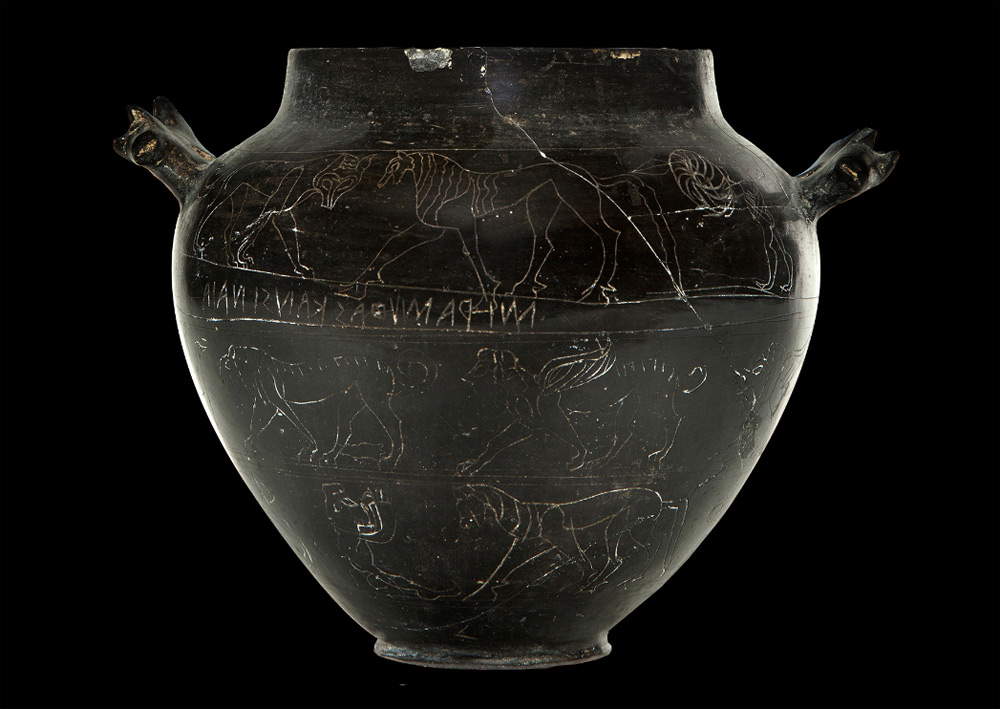

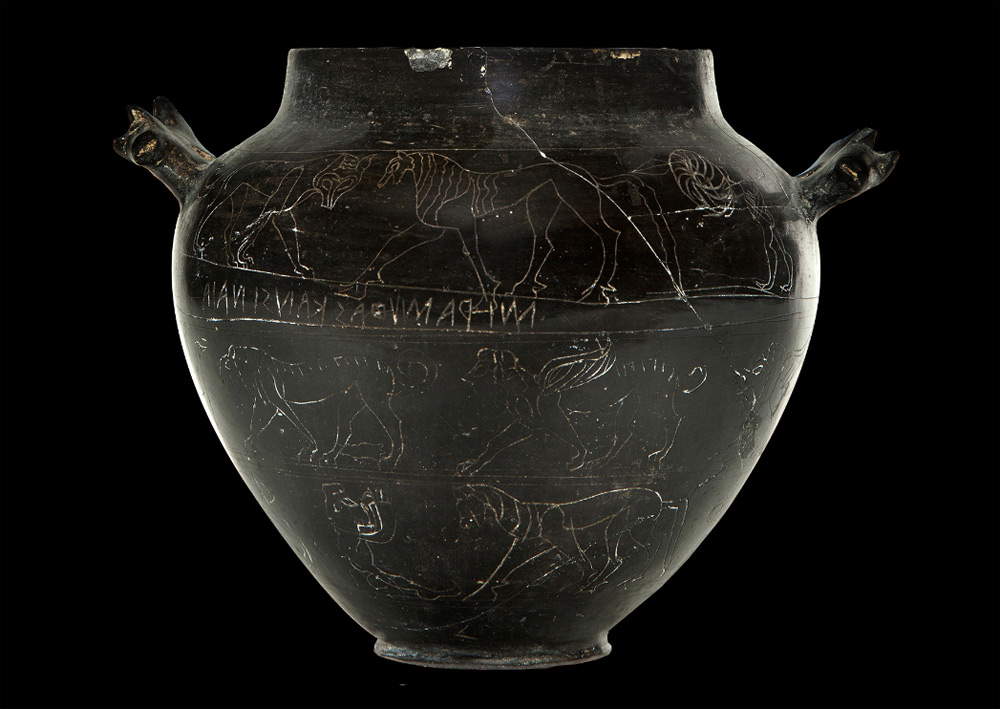

A first important aspect of Etruscan women consists in the fact that, as numerous inscriptions attest, they were endowed with proper names: in contrast, in Rome women were identified exclusively by the name of the gens, or family, to which they belonged (Tullia, Iulia, Cornelia, and so on: in the case where there were two women in the same family, they were referred to by numerals, such as prima, secunda, tertia, or by the adjectives maior and minor if there were two). Only from the late republican age would Roman women begin to use the cognomen (a kind of nickname). Many attestations of female proper names of Etruscan women have survived: Velelia, Anthaia, Thania, Larthia, Tita, Nuzinai, Ramutha, Velthura, Thesathei. And it is the inscriptions found on the objects that tell us much about the status of Etruscan women. Thus we know that women owned objects, we know that they were able to read (explanatory inscriptions, perhaps to illustrate a decorative scene, or dedications appear on some everyday tools), and probably in some cases they may have even owned businesses. A couple of examples: at the Gregorian Etruscan Museum, in the Vatican Museums, there is a bucchero olletta (i.e., a small vessel that was used to hold food: see the article on Etruscan cooking) where the inscription “mi ramuthas kansinaia,” or “I am from Ramutha Kansinai,” is inscribed, where the owner of the vase, a woman, is identified by first and last name. And at the Louvre, on the other hand, there is a pyx, dated to about 630 B.C., on which is inscribed “Kusnailise,” which could be translated as “in the workshop of Kusnai,” where Kusnai (a woman’s name) is presumably the owner of the business.

|

| Engraved bucchero olletta with inscription (630-590 BC; engraved decorated bucchero pottery, height 12 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Gregorian Etruscan Museum). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

What kind of woman can we imagine when we think of the Etruscan woman? It should be specified that we are mostly familiar with wealthy Etruscan women, those who could afford to have themselves effigyed on frescoes or who could commission sumptuous sarcophagi from artists. Scholar Lidio Gasperini writes that “we see, in Cerveteri as in Tarquinia, Volterra, Chiusi, and Perugia, on painted walls, sarcophagi, cinerary urns, images of brides, usually lying on the convivial bed with rich and refined hairstyles, often of great effect and elegance. Nobility and gentility of dress, which go hand in hand with the nobility and gentleness of posturing, the intense and affectionate participation in one of the most collected and intimate moments of the day.” The images and artifacts that have come down to us have handed down the image of a proud, refined, gentle woman who enjoyed worldly pleasures, loved to dress well and wear fine and precious jewelry, devoted much time to caring for her body and her appearance, experimented with elaborate hairstyles, and played an important role at both the family and social levels, given also “the quantity and wealth, sometimes exceptional, of her ornaments and objects laid in her honor (and for her use)” in burials.

Here, then, when we think of the Etruscan woman, we are reminded, for example, of the images of Larthia Seianti, the lady in the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, dressed in a long tunic cinched at the waist decorated with studs and wearing precious gold jewelry, such as a pair of showy disc earrings or an armilla on her biceps, or the young Velia, a bride depicted in a fresco decorating the Tomb of the Orc at Tarquinia, and wearing a rich amber necklace, a pair of clustered earrings, and has her curly hair gathered at the nape of her neck with a netting and adorned with a laurel wreath, or the beautiful girl preserved in the Metropolitan Museum (one of the most highly evolved examples of Etruscan art, a life-size sculpture), who wears a tight-fitting tunic that highlights, without leaving much to the imagination, the forms of her breasts, and who wears elaborate and rich jewelry with depictions of deities. Etruscan women’s grave goods include several objects that tell us much about their activities: tools for weaving and spinning(hobbies that were also practiced by upper-class women, supported by their handmaids) have been found, and then mirrors, jewelry, ornaments of various kinds and unguentariums, a sign that Etruscan women must have spent a lot of time making themselves beautiful, and again horsebites that might suggest the fact that, in ancient Etruria, women moved and traveled independently, without a father or husband to accompany them. The statues and portraits also testify to a great variety of hairstyles that Etruscan women liked to try, although there are a few recurring ones: in ancient times (in the sixth century B.C.E.) it was fashionable to have a hairstyle with long braids hanging over the breasts (there could have been two, but also more), or with long hair worn back so that it fell behind the shoulders. In more recent times, on the other hand, the fashion for short hair became more popular, or hair that was gathered up: it was either held in place with a hairnet, as in the case of the aforementioned Velia, or it was combed “melon style,” that is, gathered in thick locks and pulled back. Beautiful, refined women, brides of princes but also of wealthy landowners, magistrates, politicians, and merchants, who did not lead a life enclosed within the walls of their homes, but spent a lot of time in society, participated in social events, and often went out to attend sports competitions and shows. In other words, as scholar Jean-Marc Irollo has written, Etruscan ladies “did not allow their men to exercise a monopoly on luxury and joie de vivre.”

|

| Larthia Seianti sarcophagus (150-130 BC; polychrome terracotta, 105 x 164 x 54 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Larthia Seianti’s portrait. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Portrait of Velia (4th century BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Orc) |

|

| Statue of young woman (late 4th-early 3rd century BC; terracotta, height 74.8 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Bust of woman (xoanon) portrayed in the act of mourning (first half of 6th century BC; fetid stone; Chiusi, National Etruscan Museum) |

|

| Female bust with melon hairdo (c. 200-150 BC; terracotta; Arezzo, Museo Archeologico Nazionale “Gaio Cilnio Mecenate”). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

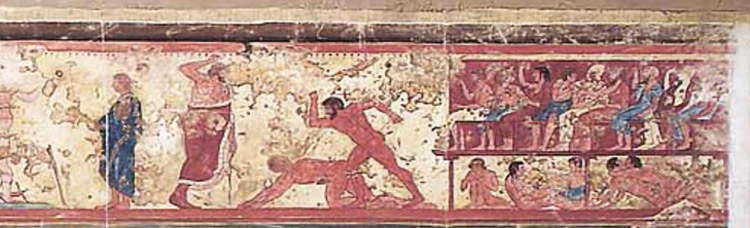

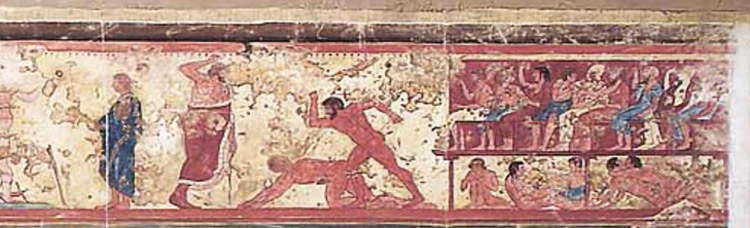

The dimension of the Etruscan woman was in fact much less “domestic” than that of the Greek woman or the Roman woman: unlike the latter, the Etruscan woman habitually took part in public life, as the Latin literary sources attest and as we can easily infer from works of art as well. In the frescoes of the Tomb of the Bigas (see the article on the Etruscans and sport) we see, in one of the stands from which spectators watched sports competitions, in addition to several women of all ages, a couple, with the woman embracing the man. This gesture, with the woman taking the lead, has been interpreted by the aforementioned Thuillier as a sign that a certain equality existed between men and women (also because, the French scholar always noted, in performances in which an audience appears, women often have seats in the first rows): it is, in the words of the noted Etruscologist, a “very modern gesture.”

So if the Etruscan woman often took part in performances, games or otherwise public events, she just as frequently attended banquets. This was a custom that, in Greece and Rome, aroused scandal, since outside Etruria, in Greek and Roman society, the only women allowed at banquets were those who practiced meretriciousness: a woman from a good family could not take part in banquets, since it was considered disreputable. Consequently, the constant presence of women at Etruscan banquets fueled the backbiting of Greek and Roman writers. Among the most famous passages on Etruscan women is that of the Greek historian Theopompus, who lived in the mid-fourth century B.C. and was the author of a very harsh judgment on Etruscan women, although by now branded as untruthful by all critics. Theopompus wrote, in what is the longest ancient passage on Etruscan women known to us, that “it was the custom among the Etruscans for women to be communal: they cared much for their bodies, exercising themselves in sports either alone or with men; they did not consider it shameful to appear in public naked; they sat at table not near their husbands, but near the first comer of those present; and they toasted the health of whomever they pleased. They are strong drinkers and very beautiful to look at.” And again, on the upbringing of their children: “the Tyrrhenians raise all the children ignorant of who the father of each one is; these boys live in the same way as those who support them, spending part of their time getting drunk and in trade with all women indiscriminately.” Theopompus enjoyed a reputation as a backbiter in ancient times as well, and apart from his assertion about Etruscan women being “very beautiful to look at” (very evident from sculptures and frescoes), several of his assertions appear to be completely unfounded: the passage about them sharing the table not with their husbands but with the first one who happened to be there is refuted by Aristotle, who assures that “the Etruscans ate together with their wives by lying under the same cloak.” That Etruscan women attended banquets together with their husbands is also a fact known from Etruscan artistic evidence. In the banquet scene of the Tomb of the Shields in Tarquinia we see a couple, husband and wife, who are eating together on the klÃne, the typical banquet bed, but this usage is also evident from sarcophagi that not infrequently depict couples lying down as if they were participating in a dinner party. In this sense, the most famous work is surely the sarcophagus of the bride and groom from Cerveteri, currently preserved at the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome: the two newlyweds are lying on a klÃne and looking ahead, embracing each other tenderly. To a much higher degree of realism then comes the so-called Urn of the Bride and Gro om preserved at the Guarnacci Museum in Volterra: in this case, it is possible that the features of the two protagonists, a couple of rather advanced age, correspond to the real ones and manifest the intention of the couple to keep their memory alive even after their demise (portraits, in fact, were placed directly above the lid of sarcophagi or urns).

|

| Reproduction of the left wall of the Tomb of the Bigas in Tarquinia (1901; oil on canvas, 204 x 516 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Reproduction of the left wall of the Tomb of the Bigas at Tarquinia, detail with the stands |

|

| Etruscan art, Slab with banquet scene (6th century BC; terracotta; Murlo, Antiquarium of Poggio Civitate - Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Etruscan art, Sarcophagus of the bride and groom from Cerveteri (530-520 BC; terracotta; Rome, Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia) |

|

| Etruscan art, Sarcophagus of the bride and groom from Cerveteri, detail |

|

| Etruscan art, Urn of the Bride and Groom (2nd-1st century B.C.; terracotta; Volterra, “Mario Guarnacci” Etruscan Museum). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

Again, regarding Theopompus’ accusations: on nudity, no banquet scenes have been preserved in which naked women appear intent on sharing the moment of conviviality with men, while on the accusation of being heavy drinkers the only data we can point out is the fact that, in many women’s grave goods, chalices, jugs and anything else that might suggest that women, in Etruria (as, moreover, also in Greece and Rome), loved wine. Finally, on the subject of child-rearing, Theopompus probably frowned upon the fact that Etruscan women, unlike Greek women, were not placed under the guardianship of their fathers or husbands, and therefore enjoyed greater freedom. Moreover, perhaps his judgment reflected the legal status of mothers, who were likely to bring up their children regardless of what the father’s status was, as opposed to in Greece and Rome, where it was the father who decided the fate of the children, and women were excluded from any decision-making role.

In art, too, the Etruscans had a different approach to mothers than in Greek art. The Greeks avoided depicting mothers in the act of suckling their children: “such a gesture,” in fact, explains the Etruscologist Larissa Bonfante, “was part of the world of the Furies, of the Eumenides, of the world of blood, of the almost animal nature of man,” which is why the Greeks refused to admit it within their figurative repertoire referring to the “normal world.” One of the major masterpieces of Etruscan art preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence is precisely a mother nursing a child: this is Mater Matuta, the Italic goddess of morning and dawn, and consequently the protector of fertility, motherhood and birth. It was found in a necropolis near Chianciano Terme, and had the function of a large cinerary urn (in fact, the head is mobile): the work strikes the observer for its monumentality, which, however, does not undermine the degree of realism that the sculptor was able to confer on the Mater Matuta (note the naturalness of the movement of the hands holding the child, but also the folds of the drapery). In the Italian territory in ancient times the cult of the mother goddess was very deeply rooted, as opposed to Greece, where, moreover, the practice of breastfeeding children was also much less widespread (Greek women of high social standing entrusted the task to nannies). This also explains why some depictions of mothers with children have come down to us in Etruscan sculpture: interesting examples are the so-called kourotrophos (“she who feeds the child”) from Veio, a votive statuette now kept in the deposits of the Soprintendenza per l’area metropolitana di Roma, la provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria meridionale, or a small bronze statuette kept in the Louvre with a mother holding her child by the hand, or the large statue, also from Veio, of Latona, mother of Apollo, caught in the act of cradling the little god. Votive statues could also represent infants, and were intended to obtain, from the deities, protection for the little ones: interesting examples are those preserved in the National Etruscan Museum in Arezzo.

|

| Etruscan art, Mater Matuta, Etruscan cinerary statue of a deceased woman with child or Italic deity of the morning mother (c. 450 BCE; terracotta; Florence, National Archaeological Museum). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Etruscan art, Mother with child (c. 500-450 B.C.; bronze; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Votive statuette with kourotrophos (molded earthenware, 13.8 x 6.9 cm; Deposits of the Soprintendenza per l’Area Metropolitana, la Provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria Meridionale) |

On Art

|

| Etruscan Art, Latona (c. 510-500 BC; polychrome terracotta; Rome, Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia). Ph. Credit Sergio D’Afflitto |

|

| Votive statuettes of infants from Castelsecco (2nd century B.C.; terracotta; Arezzo, Museo Archeologico Nazionale “Gaio Cilnio Mecenate”). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

As important as the role of Etruscan women was in the family context, however, the hypothesis that Etruscan society had a matriarchal structure has been disproved by scholars. According to the most recent studies, women in Etruria did not play a dominant role within the family: the fact that the names of the fathers prevailed in the inscriptions (although sometimes that of the mother could appear) has led almost the entire scholarly community to reject the hypothesis that it was up to the woman to hold the principal position. It is true, however, as mentioned in the opening, that Etruscan women enjoyed a freedom not known in other ancient societies. A freedom, however, that would experience heavy retrenchments as the Etruscans came into contact with the Romans. And which was lost when Etruscan civilization was “incorporated” into Roman civilization.

Reference bibliography.

- Alfonsina Russo (ed.), Egyptians Etruscans. From Eugene Berman to the Golden Scarab, exhibition catalog (Rome, Centrale Montemartini, December 21, 2017 to June 30, 2018), Gangemi, 2017

- Liana Kruta Poppi, Diana Neri (eds.), Women of the Etruria Padana from the 8th to the 7th century BC. Between domestic management and craft production, exhibition catalog (Castelfranco Emilia, Museo Civico Archeologico, February 15 to March 10, 2015), All’Insegna del Giglio, 2015

- Fabrizio Ludovico Porcaroli, Mater et Matrona: La donna nell’antico, exhibition catalog (Ladispoli, Centro di Arte e Cultura, from August 1 to November 1, 2014), Gangemi, 2014

- Jean MacIntosh Turfa, The Etruscan World, Routledge, 2013

- Jean-Marc Irollo, The Etruscans: at the origins of our civilization, Daedalus, 2008

- Antonio Giuliano, Giancarlo Buzzi, Etruscans, Mondadori-Electa, 2002

- Mario Torelli, The Etruscans, Rizzoli International, 2000

- Antonia Rallo (ed.), Women in Etruria, LErma di Bretschneider, 1989

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.