The Ethiopian manuscripts of the Casamari Abbey Library.

A collection still almost all to be studied, with various unpublished material, and scientifically surveyed in its entirety only in 2017: this is the precious Ethiopian collection of the State Library of the National Monument of Casamari, that is, the library of the important Cistercian abbey located in Veroli, near Frosinone. The presence of Ethiopian texts in Casamari’s library holdings is due to the history of relationships that the abbey has been able to weave: since 1930, in fact, it has been continuously carrying out an activity in support of Catholic monasticism in Ethiopia and Eritrea and constantly hosting young people from the African country. The beginning of the relationship linking Casamari to Ethiopia began in 1926, when Pope Pius XI sent the encyclical Rerum Ecclesiae in which he stressed the importance of Catholic missions outside Europe. Then, in 1930, Cardinal Alexis-Henri-Marie Lépicier proposed that Ethiopian and Eritrean monks interested in contact with the Cistercian way of life be hosted precisely at Casamari. Instead, it was in 1940 that the first mission to Africa was organized, with a group of monks leaving Casamari for Eritrea in order to open several houses, from Asmara to Karan, from Addis Ababa to Gondar (today only those in Asmara, Keren and Halay remain).

The presence of Ethiopian manuscripts in Casamari (there are twenty in all) thus depends closely on this history. In the census of the Ethiopian collection at Casamari, published, as anticipated, in 2017 and carried out by Antonella Brita, Karsten Helmholz, Susanne Hummel, and Massimo Villa, all from the University of Hamburg, the four scholars reconstruct the history of acquisitions: the first group of manuscripts, eleven in total, arrived at Casamari between the 1950s and 1960s, when abbot Nivardo Buttarazzi was abbot (he held the position from 1941 to 1988), while the second nucleus, consisting of nine manuscripts, arrived between 1988 and 1994 with Abbot Ugo Tagni.

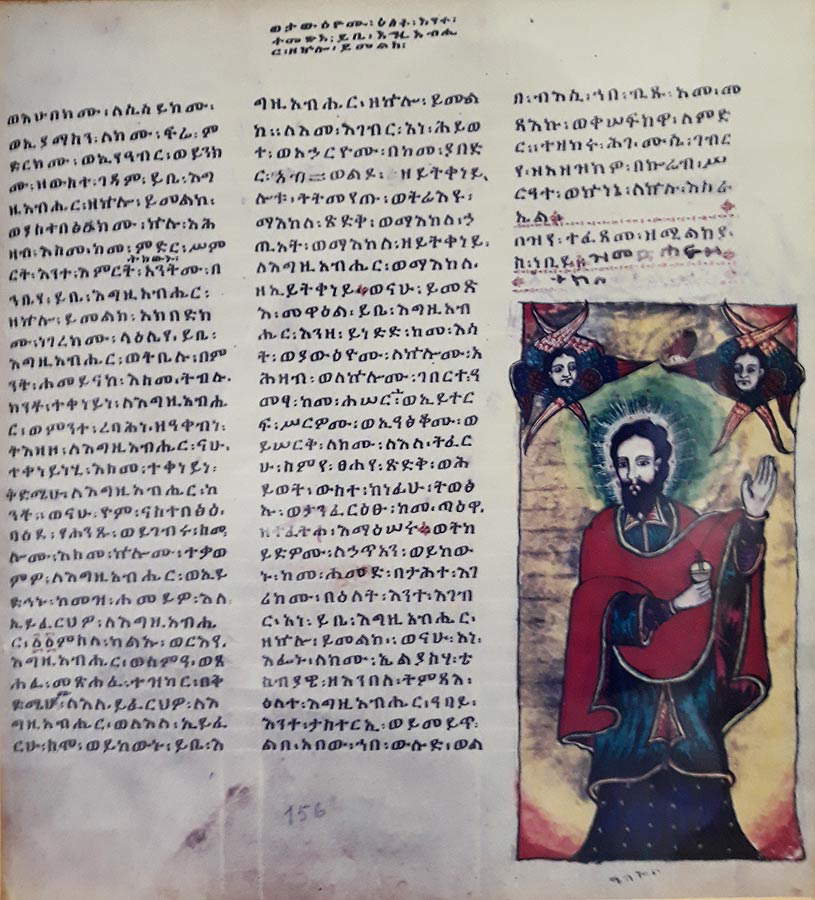

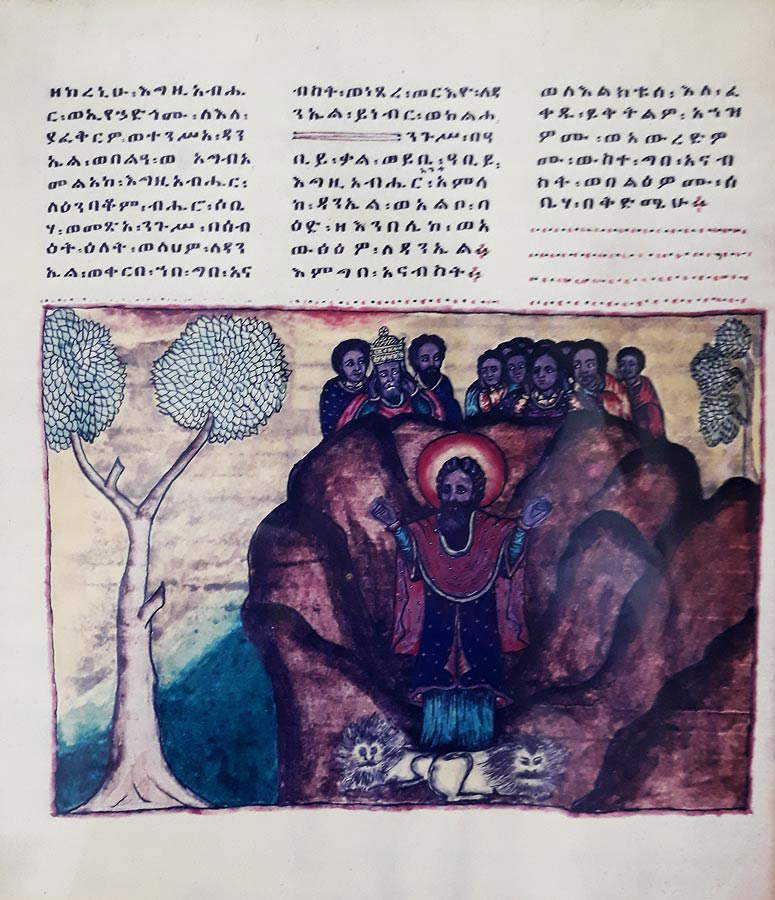

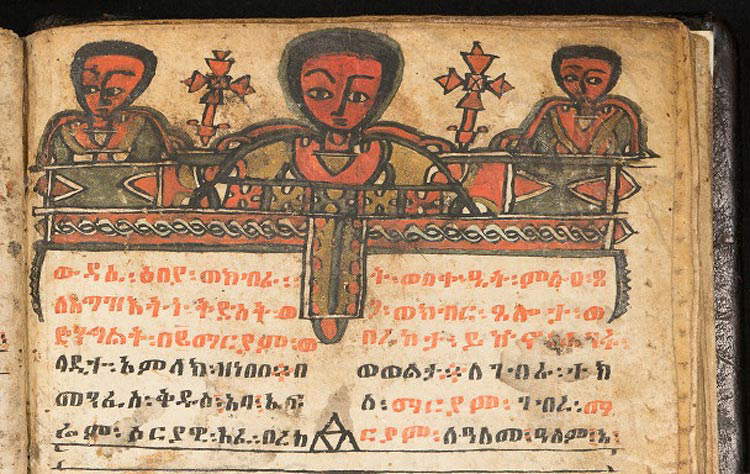

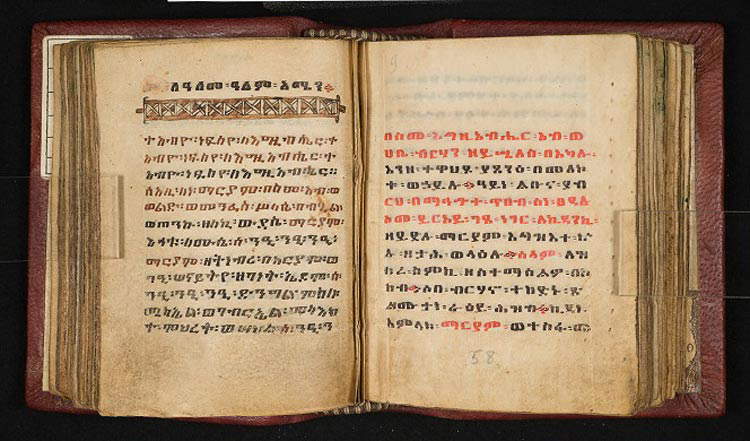

The first codex (MS 29), from the 16th or 17th century, contains some Old Testament books: the book of Isaiah, the book of Daniel, the wisdom books and an apocrypha, the book of Enoch. On the other hand, 30 is a DÄwit, or Psalter (the book of psalms) from the 18th century, while 31 contains the Gospel of John(BÇsrÄta YoḥannÇs in Ethiopian). The 32 is a 20th-century codex is a breviary(MÇÊ¿rÄf), the 33 is a 19th-century Gospel of John, the 34 is another breviary composed between 1889 and 1913, 35 contains a hymnal and dates from the 18th-19th centuries (38 and 39 are similar), and 36 has the same contents as the manuscript before it but dates entirely from the 19th century, while 37 is a collection of liturgical texts, prayers, and hymns, dating from 1881-1889.

Miniature of the

Miniature of the Miniature of the

Miniature of the Miniature of the

Miniature of the

We then move on to the second core, with MS 113, from the 18th-19th centuries, which contains a Doctrina arcanorum and a hymnodic poem, followed by 114, which includes a Lament of the Virgin(SaqoqÄwa dÇngÇl) from 1889-1926. 115 is a collection of hymns and liturgical texts, dated 1732, while 116 is a psalter from the nineteenth-nineteenth century, as is 118, which is instead from the nineteenth-twentieth century, and 120 from the nineteenth century. 117 is a collection of liturgical texts divided into two units, the first of which dates from 1682-1692 and the second dating instead from the eighteenth century, while 119 contains an antiphonary and a collection of Eucharistic hymns and dates from the nineteenth-nineteenth century. Finally, 121, the last manuscript in the collection, is a Book of Peter’s Revelation to Clement(Maṣḥafa QalemÇná¹os), a codex divided into three units: this is the most interesting and oldest codex in the collection, so far the only one that has been studied, first by Delio Vania Proverbio and Gianfranco Fiaccadori, then by Alessandro Bausi. It is divided into two units: a single sheet from the 15th century, while everything else was copied between the 15th and 16th centuries, although the QalemÇná¹os was composed between the 13th and 14th centuries (and the Casamari manuscript is one of the most valuable witnesses of this work). The Ethiopian-language work falls into the genre of apocalyptic books, consists of seven books, and is relevant in that it is considered by the Ethiopian Church to be one of its canonical books, just like the Bible.

All the Casamari codices are in the GÇÊ¿Çz language (pronounced: “ghés”), an extinct language that was spoken in the Ethiopian Empire from the fifth century BCE until the fourteenth century, but currently still used as a liturgical language by the Ethiopian and Eritrean Churches (it is, in essence, a kind of counterpart of Latin for the Catholic Church). The production of manuscripts in this language began in Ethiopia as early as the first centuries of the spread of Christianity, and today it is estimated that there are more than two hundred thousand manuscripts in GÇÊ¿Çz, twenty thousand of which are in Europe (the largest collection of GÇÊ¿Çz manuscripts outside Ethiopia is in the Vatican Library), many of them in Italian cities, including public libraries and private collections.

Some of the codices also turn up decorated with miniatures. Such is the case with MS 29, which bears three illustrations (a St. George with the dragon, a Daniel with lions, and St. Michael), with MS 33, which features a portrait of a bishop(abuna) of the Ethiopian Church, SÄmuʾel zaWaldÇbbÄ, depicted together with a lion, and again a St. George, and finally 114, where we find a St. Michael, a Virgin and Child, a depiction of Gabra Manfas QÇddus (a saint revered by the Ethiopian Church) with some wild beasts, and again St. George. Of particular interest are the illustrations in MS 29, which are in the style typical of much Ethiopian miniature art: figures that are substantially stylized but often described with great decorative minuteness (see, for example, the horse of Saint George), large, mostly monochromatic backgrounds, broad color fields with almost no chiaroscuro, very pronounced use of outline that is used to create the forms, simple but highly effective expressive gestures.

Although the earliest research on Ethiopian manuscripts now dates back more than a century, only recently has renewed interest emerged around these productions, and initiatives to map the various collections that collect them have also begun (the one on Casamari is part of a study that also involved the Castello d’Albertis in Genoa and the Biblioteca Giovardiana in Veroli). Much remains to be done, however: several manuscripts have reached us in a precarious condition and need to be digitized in order to better preserve them, there are manuscripts that are still untranslated ( QalemÇná¹os himself, despite being well known to scholars of Ethiopian manuscripts, was only translated in full into Italian in 1992 by Alessandro Bausi), a great many of which have never been produced in a critical edition or which have never even been the subject of study. A heritage, therefore, still almost undiscovered.

The State Library of the National Monument of Casamari

Casamari Abbey was founded shortly after the year 1000, when some clergymen from Veroli, with the intention of establishing a Benedictine monastic community, began the construction of a monastery on the ruins of Cereate, home of the consul Caius Marius (hence “Casamari,” or “House of Marius”). Around the mid-12th century, the Benedictine monks were replaced by Cistercians, who built the present monastery, a jewel of Cistercian architecture. After a period of splendor, beginning in the mid-14th century Casamari entered a slow decline until in 1717 a colony of reformed Cistercian monks, known as Trappists, from Buonsollazzo in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, were introduced there, giving new impetus to the spiritual, cultural and material vitality of the monastery. In the Napoleonic era and throughout the 19th century, Casamari suffered invasions, looting, fires and bloodshed. Stripped of its property in 1873 as a result of suppression laws, the abbey was declared a national monument in the following year. In 1929, Casamari, together with the monasteries it founded, was canonically erected into an autonomous monastic congregation, aggregated with the Cistercian Order. The buildings are harmoniously arranged around the cloister, the heart of the monastery and the landmark of the entire complex. A community of fifteen monks currently lives in Casamari Abbey.

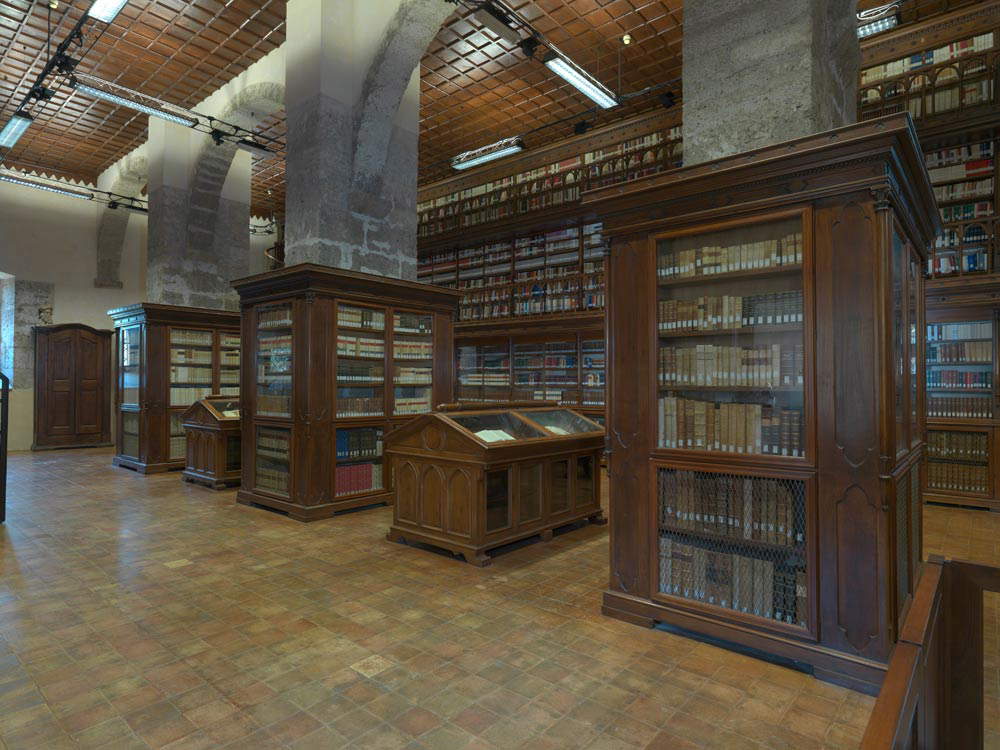

Casamari Abbey, has a prestigious library that was started as early as the beginnings of monastic life and today holds more than 70,000 volumes, parchments, illuminated codices, manuscripts and some incunabula. The library occupies the extreme part of the west wing of the monastery, where the conversi refectory once stood, and is accessed via an external staircase. The room has a coffered ceiling, supported by four round arches, which branch off from three pillars. Valuable volumes include a dozen manuscripts and some incunabula. The oldest manuscript is a Rule of St. Benedict from the late 12th century; others date from the 14th and 15th centuries. The library is one of the most important rooms in the monastery, because it holds not only books for liturgical use, but also those that the monks personally consult for study, as they are not allowed to own their own. The abbey also counts on a Museum-Pinacotheque: in some rooms are in fact exhibited archaeological finds, most of which were found in the vicinity of the abbey, including statues, marble cippi, pagan are, terracotta votive offerings, coins, epigraphs and a tusk of elephas meridionalis, as well as some canvases including The Alms of Saint Lawrence by Giovanni Serodine.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.