The dreamlike expressionism of Francesca Banchelli

One could start from a first, single noun to introduce the art of Francesca Banchelli (Montevarchi, 1981), one of the most interesting names in young Italian painting: “encounter.” It is perhaps the first word that comes up every time you look at her paintings, always populated by the most diverse, surprising and unexpected encounters. And she too, for that matter, repeats it frequently. Encounters between souls moving against the background of desolate deserts. Encounters between self and the depths of one’s interiority. Encounters between the personal self and the collective self. Encounters between people, animals, natural elements within dreamy landscapes, constantly balanced between the real and the surreal. Encounters between the dimension of the everyday and that of memory. Encounters that occur within compositions that know neither space nor time. Encounters also of a formal nature, between figuration and abstraction: it is a difficult task to try to decipher the many images that the Tuscan artist deploys on her colorful territories, first of all because painting is for her a medium that expresses, rather than describes, and above all it is a medium that allows her to express what otherwise could not emerge.

In the space of the painting, she explains to me, “I find a space that begins to grow out of proportion, where connections between small events begin, becoming a constellation of events, reaching a kind of space-time alter. It is about the encounter between me, my unconscious, my imaginary, my tensions and the collective, an encounter between me and the world, a kind of reconciliation, where through this revolutionary encounter between the individual and the collective a reconciliation with nature is also possible. A new way of understanding each other, an attempt to understand each other better, a revolutionary space where there is finally an understanding at a deeper level, although not a linear one, because it has to do with a timeless imagery and something beyond connections as we know them.” It is a painting that is anything but immediate, because it is not only a changing and ever-changing synthesis of her way of understanding our relationship with everything around us (and consequently, to try to enter these paintings, one needs a certain inclination to openness, acceptance, and perhaps one also needs to be a little empathetic), but it also preserves traces of all Francesca Banchelli’s experiences.

The relationship between the Tuscan artist and painting began from the time she was in school, at the Liceo Artistico di Porta Romana in Florence, and then deepened her technique at the Accademia di Belle Arti. Soon after, however, a separation: Francesca Banchelli moved away from painting for some time to experiment with a totally different language, that of performance, which took her first to London, then to Barcelona, and for some time even to Brazil. What the artist was looking for was contact with the world: it was through the exploration of this medium of expression so different from painting that she became interested in “the relationship between the individual and the collective, approaching performance as an experience of possibility and risk,” as she herself stated in an interview with Artext magazine. Then, after earning a master’s degree at Central Saint Martins in London in 2010, here is the gradual return to painting, but without losing sight of performance. And if the big European cities and the habit of performance art introduced into Francesca Banchelli’s horizons the themes of investigation of the self and relationships with others, the possibility of measuring herself with China, where she spent two months of residency after graduation, made inescapable the entry of the age-old dialectic between nature and culture into her art.

Here then, Francesca Banchelli’s painting, in her most recent works, has become the sum of all her experience. “Painting and performance are linked, they go hand in hand,” she continues. “The crucial point, from which the painting on one side and the performance on the other side unwinds, is the concept at the basis of each project, which has a process of development even quite long, which I develop through drawing. The drawing that underlies everything in my work, a basic ground of both how I visualize performance and painting.” It is not drawing traditionally understood as preparatory work done in preparation for a final drafting. The drawing is a kind of introduction to the work, an incipit. "Then each of the two practices develops with different possibilities: painting dealing with the infinite access between the events of the world and the unconscious, infinite visions crossing unthinkable worlds. And on the other hand, performance that starting from a basic setting overrides control through the risk, uncontrollable, of live performance. In fact, in my performances the personalities I invite are never numbers, but real contributions of real people, not choreographed, who have the chance to meet in that incredible space/time dedicated to live time, where they have the chance to meet again without mediation, create or hint at small new societies, inevitably making uncontrollable events happen."

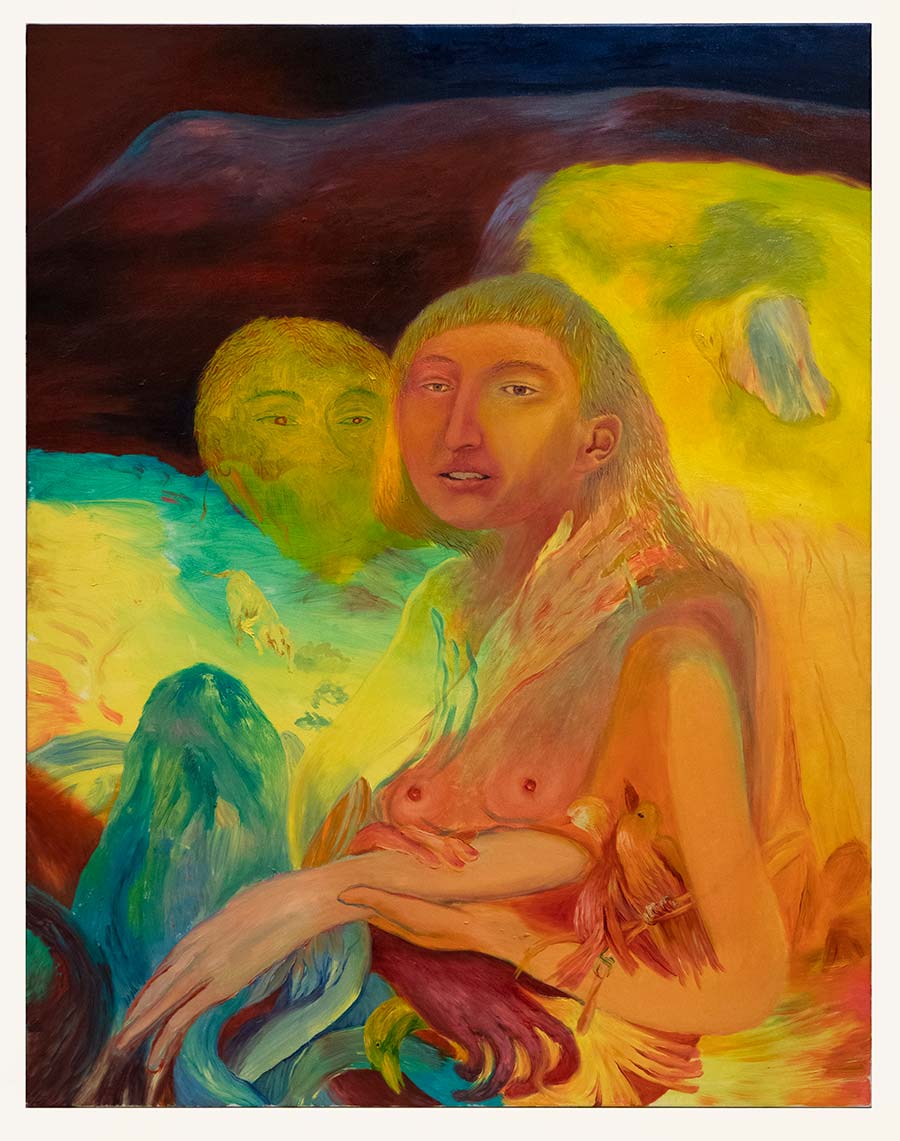

His studio, nestled in the woods of Valdarno, in a tiny medieval village of a few stone houses just above Reggello, overflows with papers and watercolors, which seem almost atoms of his larger compositions, ideas for what will later take shape on canvas, but which are also capable of living a life of their own, autonomous they are small scenes outlined with an almost instinctive attitude, they are emaciated figures on undefined backgrounds, humans and animals interacting, visions of air and water, fragments of dreams. Even the early paintings had this almost gestural character, which seemed to translate into shapes and colors a disposition of the artist, amplified also by natural happenings(Metaphysical Optimism or even better Beach Event and Man taking a shower, modern landscapes-states of mind where the lyrical flowing of water alludes to life itself), to the point of verging on mystical vision(Eye in the sky). Then his painting became more relaxed, meditated, more open to figuration(Romance), though always populated with unrecognizable views, no-man’s-lands, indecipherable foreshortenings where it seems that something is always about to happen, or where something has already happened. However, quickly scrolling through Francesca Banchelli’s images, one will realize that motifs that are usual to return and remain unchanged throughout the artist’s career persist in her paintings, as Ángel Moya García noted, “Regardless of the language chosen, there are recurring elements: stones, as having always been there; time, as something that unites past, present and future; animals (dogs and birds predominantly), as elements that bring living beings on earth together; and the human being, as a presence that is never defined and that becomes the bearer and transmitter of multitude and at the same time becomes a witness to change.” There is a lack of clear distinctions between inside and outside: in A bird, a girl, a bird, a boy, a bird, a man, a 2016 painting, we see a room enclosed on all sides by glass walls, which is, however, confused with the space that surrounds it all around (and we do not even understand whether we are in front of the sea, or among the hills), and where we witness strange encounters between birds and people, while in the lower right corner an agave seems to want to swallow the whole scene. Encounters that are always an allusion to one of the necessities of human beings: the ability to make connections with other species that inhabit the planet.

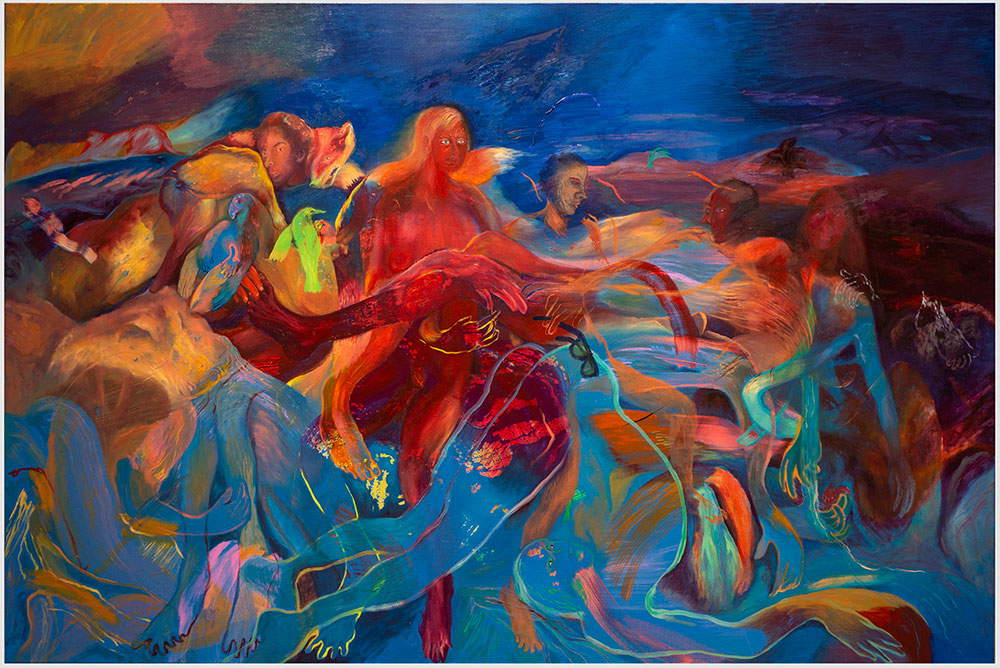

However, there is no shortage of more contingent situations: Francesca Banchelli, in recent years, has pursued with some insistence the theme of fugitives, which also gives the title to one of her performances(The Fugitive, born moreover from a series of drawings where the artist imagined encounters between humans, animals, natural elements such as rocks and plants in unknown environments), and which also returns in her paintings. His fugitives, wrote Eva Francioli, “can be considered as figures who flee from social, political, economic, and climatic realities and find themselves in other contexts, in which it is precisely the status of fugitives that gives them a specific identity. ”They are “real and at the same time imaginary figures,” living “in our time and space, inhabiting our imagination, our nightmares and our fantasies. One escapes in order to seek something better elsewhere, but one also escapes in order to transcend the limits of one’s existence, one escapes with the imagination, and escape acquires the contours of an escapism, ending up resembling the concept expressed by Emmanuel Lévinas: ”Escapism is the search for the marvelous, which can break the somnolence of our bourgeois existence. It does not, however, consist in freeing ourselves from the degrading servitudes imposed on us by the blind mechanism of our body, since this is not the only possible identification between man and the nature that inspires him with horror. [...]. It is not only about getting out, but also about going somewhere. On the contrary, the need for escape is found absolutely identical at every juncture to which his adventure leads him as a need; it is as if the route he has traveled cannot diminish his dissatisfaction.“ Escape, in Francesca Banchelli’s works, becomes almost synonymous with the human condition, not least because escape entails a subsequent step: the reconstruction of a community, of a small society, in a revolutionary moment that ”resets hierarchies to zero," as the artist further explains to me. This is seen in Fires, an oil on cotton that originates precisely from The Fugitive. The scene is set on what appears to be the bank of a river, in the distance we can see red glimmers that suggest, rather than a sunset, a fire, hence the title of the painting. Some people are immersed in the water, while others are just outside, watching a group of brightly colored dogs, not far from the humans. Dogs, as anticipated, are recurrent presences in Francesca Banchelli’s iconographic repertoire, but they never have a precise and defined role: sometimes guardians, watchmen and reassuring presences, sometimes menacing beings, looming shadows.

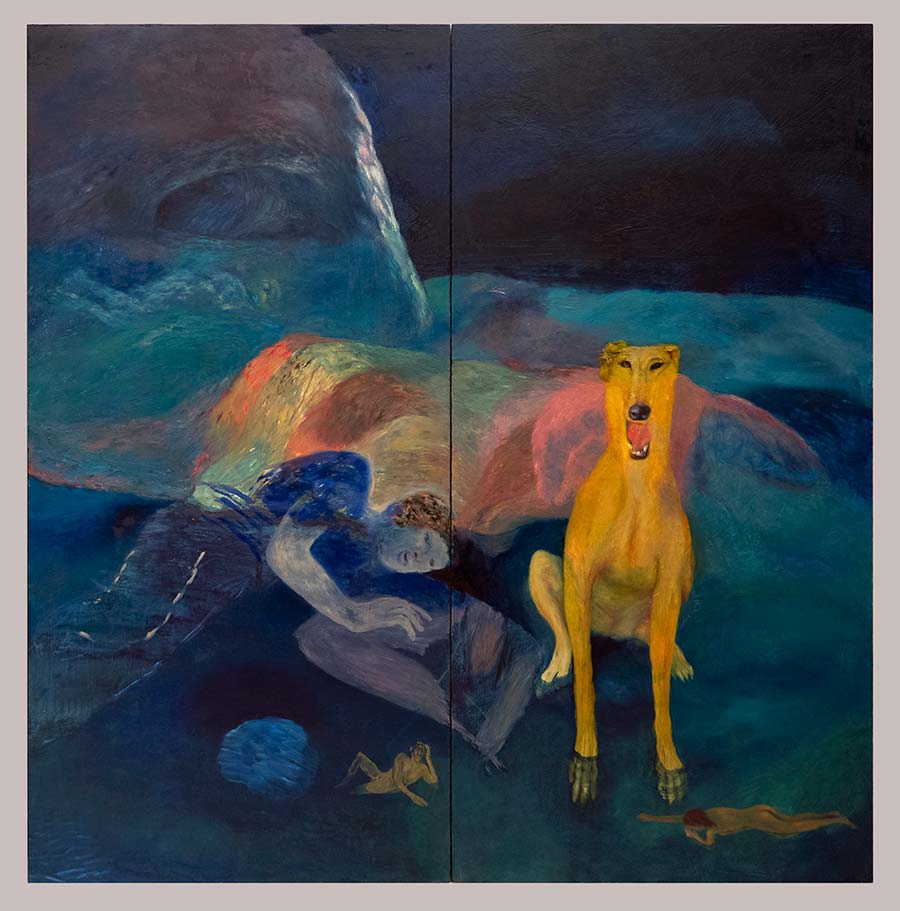

In Fires an apparently relaxed encounter contrasts with an oppressive atmosphere, an uneasy sense of expectation prevails, and as is often the case in Francesca Banchelli’s paintings, it seems as if something is about to happen. A “passage of energies,” the artist tells me, evoked by the use of colors. The impact with Francesca Banchelli’s colors hardly leaves those who admire her paintings indifferent. The bright, unreal and saturated tones recall the art of Antonietta Raphaël, but the entire Roman School, from Mario Mafai to Scipione, seems to be a constant point of reference for Francesca Banchelli’s art, which spans the entire twentieth century, feeding on the coloristic violence of the Fauves, engaging in a confrontation with Sandro Chia and the Transavanguardia (in whose presence Francesca Banchelli’s art appears more restless and visionary), sometimes recalling certain abstract paintings by De Kooning, or the contemporary research of artists such as Miriam Cahn and Peter Doig. Francesca Banchelli brings all these suggestions together in a kind of dreamlike expressionism that perhaps finds its peaks where the artist tends more toward figuration, as is the case in one of Francesca Banchelli’s most important paintings, the Silent Dogs, to which she herself attaches an extremely relevant value, a work born during the period of Covid-19’s first confinement as a gradual discovery of nature, as an attempt to reconnect with the world, as a feeling of being a part of the whole and at the same time a whole.

We find the same dog with a slender physiognomy in Event, one of Francesca Banchelli’s most recent works, exhibited in the summer of 2020 at the exhibition I cani silenziosi se ne ne ne ne ne vai via, her first solo show in an Italian museum (the Museo del Novecento in Florence), curated by Sergio Risaliti and Eva Francioli. The animal stands at the feet of a couple immersed in a liquid landscape where a blizzard seems to be brewing: the two characters seem to be at the mercy of events, they look ahead of them but perhaps do not even know quite where to look, their bodies merge and search for each other, they are intent on not being overwhelmed, they are trying to resist together, the dog looks at them perhaps to make it clear that he is there, that he will stay with them (and who knows if he is really silent, judging by his attitude). Francesca Banchelli painted Event while the world was being shocked by the Covid-19 epidemic, and it is far too simplistic to find, in this whirlwind, an allegory of what was happening in those days: it would be too descriptive, too didactic. Instead, Event seems to be an allegory of possibility, a deeper reflection on what was happening in the early 2020s. At the Museo del Novecento in Florence it had been exhibited along with a work from the 1930s by Scipio, Apocalypse, and the very phrase The Silent Dogs Go Away is taken from a poem by Scipio: “At sunset a sheep / Made a lamb. / It came out all woollen, with blood / the heart the voice. / The men come out / and go away, / the silent dogs go away, / the trees wait for the dark / to ignore each other, / the fragrant grasses set out / on their way. / The owls shout, everything moves / and anguish fills the air / with restlessness.”). The choice of dialogue, however, had been made when coronaviruses were still a subject for specialists: Francesca Banchelli had found a certain resonance in the work of the Roman painter, who in his plates dedicated to theApocalypse of John gives shape to his prophetic visionaryness, describes landscapes devastated by terrible events and populated, however, by conscious and at the same time fearful figures, capable of accepting their destiny but nevertheless capable of placing hope, set out towards unknown territories, exactly like the figures of Francesca Banchelli: in her paintings one perceives the same sense of suspension and indeterminacy that grips anyone who observes Scipio’sApocalypse. And, perhaps even more importantly, Francesca Banchelli believes that she has identified in Scipio an artist who, like her, considers the work of art as an “epiphany and gnoseological event inescapable to the evolution of the human species” (so said the presentation of the exhibition). In other and simpler terms, art, for Francesca Banchelli, is a medium that human beings cannot do without, and it must be an assiduous presence in everyone’s life. “In this way,” the artist told Sergio Risaliti, “it becomes a strong demiurgic constancy for people, a sense of belonging to the community, to history, to the future, to our nature, and to the world in which we live, a cure. If art could permeate into daily life through common media it could be part of the collective debate, speak to people.”

In her view, art should be a spontaneous acquisition, a familiar subject, a kind of fluid to be immersed in as naturally as possible, and a mature community should accept it as an important part of itself: the example of England comes to mind, where in regard to art there is not, paradoxically, that reluctance that is often felt in Italy, but rather it is viewed with great interest even by those who in their daily lives deal with anything else: “art is perceived as a good, something that does good, something that enlightens the soul and is part of the growth of a society, not a fad,” she explains. Already in the text she had written for the exhibition Silent Dogs Go Away, Francesca Banchelli emphasized that hers, however, is not activism: it is only about “recovering one’s place as an artist as a human being.” There are then ways to make a society more sensitive and more attentive to art: “the problem is to want it,” starting with education and schools. As an example, he tells me, “I often think of my parallel life in which a part of me was driven toward medicine. Something I never left completely, as if I was constantly living with this part of me as well, the ’cure’ always fascinated me. An important person, a collaborator, however, said to me one day ’Your paintings cure the soul.’ Indeed, art is also important for this. In front of my works I often hear that there is a movement that captures, that engages the soul in some way, and that is important to me. Not because I have a formula to make it happen, but because I find reason in this closeness between art and soul. The possibility of establishing an encounter outside of mediations through the work for me is revolutionary and fundamental.”

And it is precisely in this possibility that perhaps the highest and deepest meaning of Francesca Banchelli’s art is to be found. Perhaps this is why her paintings appear so impetuous, it is for such reasons that her works transfigure the everyday without denying it, but rather by including it in a constant tension, in a whirlwind that involves the lived, the dream, the emotions, the real, the imaginary and that is made of paintings with a magnetic face, with bold colors capable of rereading with originality the twentieth-century substratum from which her images sprout, with fluid and delicate brushstrokes, paintings devoid of any spatial and temporal reference (and it could not be otherwise, since in her works live together present, past and future, and since the art of Francesca Banchelli inexorably conveys a cyclical conception of time), filled with characters and figures that not infrequently indulge in almost explicit allocutions (in Fuochi, for example, this role is entrusted to the dogs: they turn toward us who observe them, point their eyes at us, channel our attention to what is happening in the painting). These are the means by which the Tuscan artist aspires to the maximum involvement of the relative, and by which she substantiates her attempt to drag him inside her visions, or inside her “encounters” as she would perhaps say. Her paintings, even in the complex stratification of their allegorical references that include much of the artist’s subjective sphere, nevertheless manage to speak a universal language precisely because at first glance they appear so engaging, endowed with an explosive immediacy, moved by a poetry that is powerful and delicate at the same time. Connecting to others, meeting one another through art to recover the meaning of what we do. This is the calm and silent energy unleashed by Francesca Banchelli’s works.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.