The doors of the Baptistery of Florence, Lorenzo Ghiberti's masterpiece

On November 23, 1403, Lorenzo Ghiberti (Pelago, 1378 - Florence, 1455) signed the contract for the construction of the North Door of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence. This was the final outcome of the competition announced in 1401 by theArte di Calimala, the guild that brought together textile merchants, which had been responsible for the management of the Baptistery for centuries. At the beginning of the 15th century, this architecture was still the main symbol of Florence, making it immediately recognizable in painted images. This place had great significance for the Florentines, not only from a religious point of view, but also from a civic one: Dante Alighieri, in Canto XIX of theInferno, refers to it in an affectionate and familiar tone as “my beautiful San Giovanni.” The Baptistery held this role until 1436, when the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi (Florence, 1377 - 1446), became the new symbol of the Tuscan city.

Conventionally, the 1401 competition marks thebeginning of the Renaissance: however, it is good to remember that artistic processes are always more complex than the indication of a single date. At the opening of the new century, the predominant artistic culture in Florence was late Gothic, but within a few years the foundations of the new Renaissance art began to be laid.

For the 1401 competition, contestants were asked to create a tile depicting the iconography of the Sacrifice of Isaac. The fame of that competition is especially linked to the artists who took part in it: seven participated in the competition, including Jacopo della Quercia (Siena, c. 1374 - 1438) and Filippo Brunelleschi. It is precisely the comparison between the latter and Ghiberti that is highlighted and has taken on almost mythical characteristics, because in their rehearsal for the competition they presented two different artistic visions, although both could be considered modern. Today it is possible to observe this comparison closely at the Bargello Museum in Florence, where these two panels are preserved. The artists were supposed to deliver the proof within a year. A time that may seem long, but one must consider the difficulty of the technique of making it, lost-wax bronze casting. Ghiberti, who reported the affair in his Commentarii elaborated between 1452 and 1455, prevailed, proposing his version of events.

The art proposed by Ghiberti was appealing and at the same time reassuring in the eyes of the patrons: in fact, he was able to maintain some elements that could please the patrons’ taste, but with some updates. He was the youngest among all the competitors, and that victory represented an incredible opportunity for him, because thanks to that success he gained prominence on the Florentine art scene, which was in great turmoil. His economic status also improved markedly and he became one of the richest artists in Florence.

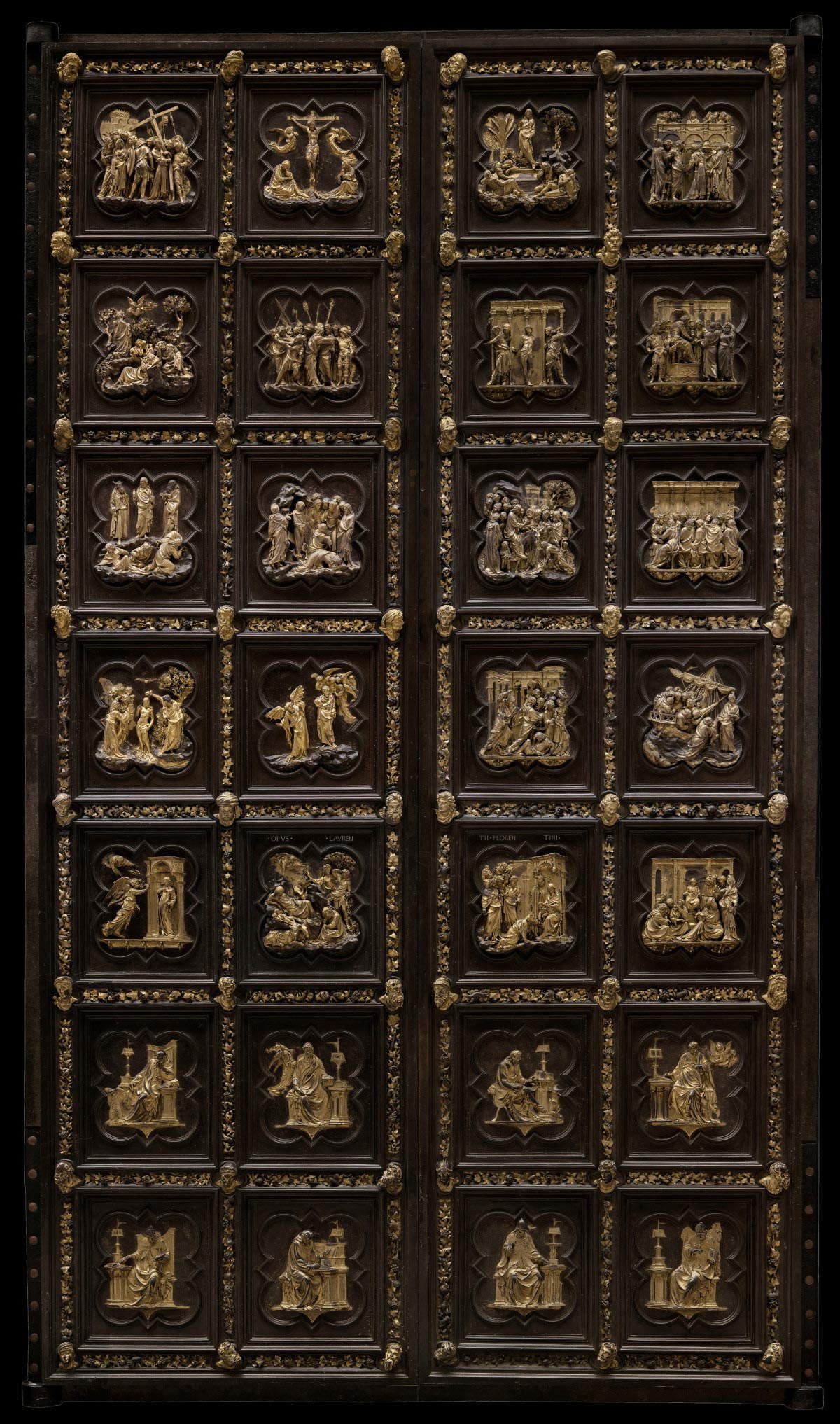

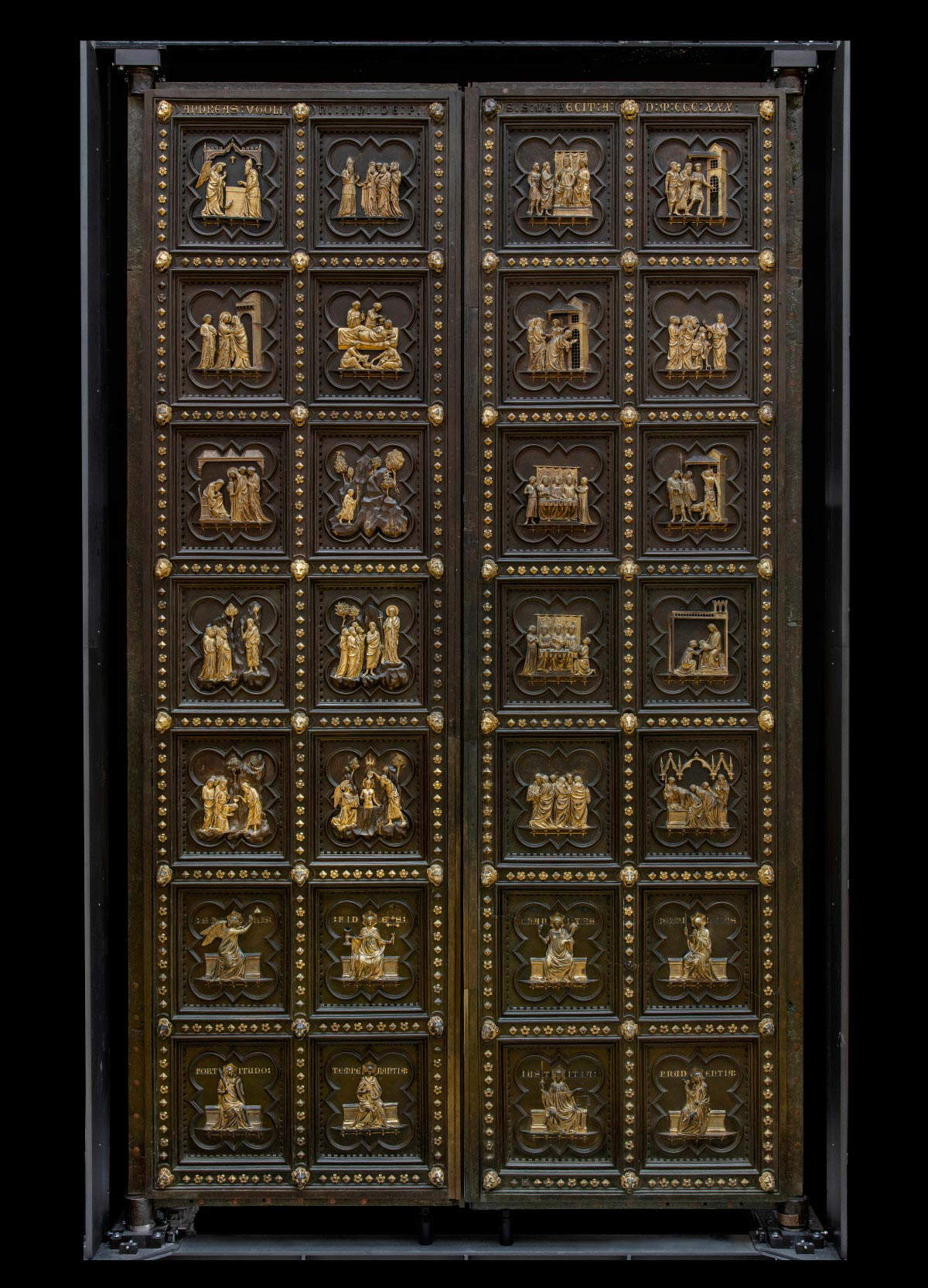

The structure of the North Door echoes that already made between 1330 and 1336 by Andrea Pisano for theSouth Entrance, repeating its pattern: twenty-seven panels are arranged in seven bands of which five, the upper ones, illustrate narrative scenes, while the lower two contain single figures. Compared to Andrea Pisano, Ghiberti chooses a different solution for the framing of the scenes, set within a poly-lobed frame: in fact, Ghiberti proposes a decoration with ivy shoots and small animals, the presence of which can be noticed only with close and careful observation. Insects such as grasshoppers, cicadas and beetles, lizards, snakes and small crabs can be spotted: it seems like observing the decoration of an illuminated page. At the corners of each tile are placed heads of prophets and sibyls, forty-eight in total, creating a play of gazes not only with each other but also with the viewer. Among the various faces, there is also that of the artist, who characterizes his own self-portrait with the mazzocchio, a typical Florentine headdress of the time.

The construction of the North Gate lasted for decades and entailed a very large expense for the Art of Calimala. The contract of November 23, 1403 was signed by father and son, Bartolo and Lorenzo, and in it it was stipulated that they were to deliver three tiles a year. A clause ensured that the figurative parts would be worked on directly by Lorenzo, to guarantee the level demonstrated in the Sacrifice of Isaac. More mechanical work was reserved for assistants: it should be noted that these included such important names as Paolo Uccello, who was little more than a child, but also Donatello, who worked on Ghiberti’s team between 1404 and 1407. In 1407 a new contract was signed, this time signed only by Lorenzo. Originally the iconographic program was to depict stories from the Old Testament, but when the construction site was already underway, the commission changed its mind: in fact, it was chosen to depict scenes from the Stories of Christ, introduced by eight panels with the Evangelists and the Fathers of the Church. The order of the panels should be read from bottom to top. The first story depicted is that of theAnnunciation: the body of the Virgin, surprised and frightened by the sudden arrival of the archangel Gabriel, arches with a sinuous movement that still has a decidedly late Gothic flavor, but on the threshold of an architecture that is already partly classical. The next stories depict the Nativity and the Adoration of the Magi. The latter is a subject particularly dear to late Gothic Italian art, because it allowed for imagining exotic details and for grappling with the depiction of various aspects of nature. Ghiberti, however, departs from this imagery, inserting as the only exotic element a monkey on the shoulder of one of the characters following the Magi. With the Baptism of Christ, the sculptor organizes the space in a decidedly balanced manner, not disdaining, however, the sinuosities of late Gothic art, which he uses to elaborate the posture of Christ’s body and the sweeping, scenographic movement of the Baptist’s arm. The sixth tile presents the episode of the Temptation of Christ, and then moves on to the Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple and the Flagellation, characterized by the presence of architecture, which struggles to find a harmonious interaction with the human figures. As the narrative progresses, the scenes become more crowded, and Ghiberti manages to skillfully balance elegant linearism with details of naturalism. The elegant and subtle line is one of the hallmarks of Ghiberti’s art, making it valuable in the eyes of the viewer and highly valued in Florence. In the field of painting, at this time the most stringent comparison in the Florentine scene was with Lorenzo Monaco, who, however, lacked the naturalistic attention that was instead well present in Ghiberti’s work. It would be necessary to wait until Gentile da Fabriano’s arrival in the city in 1420 to harmoniously combine these two aspects in painting as well.

The panels were probably made between 1415 and 1420. Later, Ghiberti’s worksite focused its work on the creation of the more properly architectural parts: the jambs, the architrave, and the structure of the two wings that would house the panels. Archival research has shown that between 1421 and 1422 Ghiberti hired three Burgundian specialists to cast the bronze frames, a very complex operation that required specific skills. The work was inaugurated on April 19, 1424. Initially, it was mounted on the east-facing entrance, the one in front of the cathedral. It remained in that position for less than 30 years, until it was replaced by the second door that Ghiberti would make for the Florentine Baptistery and that Michelangelo would call "of Paradise." On that occasion, the wings of the first door were placed on the northern entrance, thus definitively taking the name North Door by which it is still referred to today. The work was greeted with enthusiasm and admiration by the Florentines. Ghiberti’s fame had grown so great that in October 1424 he is witnessed in the retinue of Palla Strozzi, the wealthy Florentine banker who commissioned Gentile da Fabriano’sAdoration of the Magi, who, together with Giovanni de’ Medici went as ambassador on behalf of the Florentine Republic to Venice in search of alliances against Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan. This fact testifies to how Ghiberti was considered one of the leading artists on the Florentine scene, so much so that he was exhibited as the Republic’s greatest artistic glory beyond its borders. Ghiberti’s fame soon surpassed the Florentine milieu and, through various channels, his artistic culture spread to various parts of the Peninsula.

The new commission was not long in coming. This time there was no competition; in fact, the commission to make the doors for the third and final entrance to the Baptistery was a direct one: this building site would accompany Ghiberti until the end of his career. In a letter of 1424, the future chancellor of the Republic Leonardo Bruni hypothesized the iconographic program of the new door, imagining the realization of twenty panels with Stories from the Old Testament and eight prophets, always following Andrea Pisano’s primary scansion. Ghiberti, on the other hand, conceived and realized the work in a totally different way than the previous one: in order to depict the episodes of the Old Testament narrative, in fact, he decided to make ten large reliefs of quadrangular shape. The artist now considered the polylobate frames of the previous panels, whose style was anchored in late Gothic taste, outmoded, preferring the simplicity and immediacy of the square form. Influencing this choice was the work for the baptismal font of the Baptistery of Siena (1416-1434): Lorenzo, in fact, is credited with the design authorship of this work, in which he was again confronted with Jacopo della Quercia and, above all, with Donatello, who created the famous panel with Herod’s Banquet. Moreover, the Florentine artistic scene was rapidly evolving: Brunelleschi was busy on the San Lorenzo building site, Donatello was working on the Prophets for the Duomo bell tower, and Masaccio was depicting a new vision of humanity on the walls of the Brancacci Chapel. Ghiberti remained no stranger to the new artistic stresses.

Even in this new worksite among the collaborators were prominent names, such as Michelozzo and Benozzo Gozzoli (who arrived only in 1444): Lorenzo’s two sons, Tommaso and Vittorio, also participated. The latter would pick up his father’s legacy, as evidenced by the presence of his self-portrait on the new door, next to that of his father, positioned in two oculi of the frame. The only signature affixed to the work, however, is Lorenzo’s “[Opus] Laurentii Cionis de Ghibertis mira[bile] arte fabricatum.” The reading order of the new casements is different from the previous work: this time one must follow the events from top left, continuing downward. The first tile contains the Stories of Adam and Eve, while the next contains the Stories of Cain and Abel. Already from these first two panels, one can admire Ghiberti’s mastery in handling the various levels of depth in the relief. Next, there are Stories of Noah and the Ark and Stories of Abraham. Next are those of Isaac and Joseph. Finally, are the Stories of Moses, Joshua and David, concluding with Solomon meeting the Queen of Sheba. In the frames, however, Ghiberti makes small niches in which to insert Old Testament figures and oculi with human heads (including the portrait of his son Victor and his own). Each tile depicts not just one scene, but several episodes from the same group of stories.

The new quadrangular form favored the development of the narrative dimension. In order to succeed in incorporating the multiple moments of the narrative, Ghiberti organizes the composition by taking advantage of the various levels of depth through the use of different sculptural and goldsmithing techniques and demonstrating his ability to employ the new science of perspective. The work is designed to be viewed from a certain distance, thus changing the relationship between observer and work from the previous intervention. The figures in the foreground are decidedly overhanging, and in places the high relief shows almost full-length workmanship, protruding from the frame. Gaining depth in the composition, the thickness of the figures gradually thins, down to a few millimeters. The relief that barely emerges from the surfaces is of such pictorial sensitivity that it achieves unprecedented results. Ghiberti’s drawing continues to be characterized by an elegant and sinuous line, which in these panels finds a wider space to express itself and materialize in figures with an aristocratic attitude. Ghiberti tends toward an idealizing figuration, maintaining attention to naturalistic details.

The door was finished in 1452. As already anticipated, it was decided to mount the new doors in the entrance placed in the eastern facade, displacing those with the Stories of Christ, placed only thirty years earlier. This was a complex and costly operation: it was not dictated by iconographic reasons, but only by the enormous admiration that Ghiberti’s new enterprise aroused: in fact, it was judged so beautiful that it had to be destined for the entrance in front of the Duomo.

The Florentine sculptor and goldsmith would say of himself : “few things have been made of importance in our land if they have not been designed and ordered by my hand,” demonstrating the high regard in which he held himself and his work. And he was an artist who was recognized, already living and then in later centuries, with great fame.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.