On the walls of Torre Aquila, located at the southern end of the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trent, the seat of prince-bishops from the 13th to the 18th century, is one of the most famous secular cycles of international Gothic, that dedicated to the depiction of the months.

The exact date of this tower’s construction is not known, but it is documented that, towards the end of the 14th century, the incumbent bishop George of Liechtenstein (Nikolsburg, c. 1360 - Sporminore, 1419)commissioned its renovation with the aim of using it as a strictly private space. The commission of the cycle of months can also be traced back to this personage. George of Liechtenstein came from an aristocratic family that had large estates in Moravia (a region in today’s Czech Republic), and he took up his bishopric in Trent in 1391, after having been provost of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. The prince-bishop intended to reassert princely rights over Trent and pursue a project of feudal restoration, consolidating his authority over the principality and restoring its finances. This intention was also supported through a number of important artistic commissions, which have come down to us in much smaller numbers than at the beginning. This attitude of his, particularly the Torre Aquila commission, was significant for the area as several aristocratic families in the region decided to commission several secular cycles for their residences. Thus we count the important cycle for Roncolo Castle, the one for Castel Chiaro (now practically lost), for Wendelstein Castle, for Schrofenstein Castle, and finally for Montechiaro Castle (in the early 20th century the frescoes were detached and taken to the Ferdinandeum Museum in Innsbruck, today’s Tiroler Landesmuseum). The feudal restoration project failed: in 1407 George of Liechtenstein was imprisoned and forced to leave Trent. A memory of this is preserved through an inscription on a fragment of a fresco on the top floor of Torre Aquila (these paintings can also be traced back to the same hand that made the cycle of months).

The cycle of months in Torre Aquila is a valuable visual document of both courtly and peasant life at the end of the 14th century in the Trentino region. The months, in fact, are not succinctly indicated through a single activity or element, as was the case in the past, but through a more articulated depiction, in which within the landscape marked by the passing of the seasons, scenes of peasant and courtly life outdoors alternate. Activities related to agriculture, animal husbandry and crafts are depicted with great accuracy and realism. In particular, agricultural implements are found described identically in Paul Scheuermeier’s volume Bauernwerk published in the mid-twentieth century.

|

| Eagle Tower as seen from the southwest. Ph. Credit Matteo Ianeselli |

|

| The cycle of the Months of Torre Aquila |

|

| The cycle of the Months of Torre Aquila |

|

| The Cycle of the Months of Torre Aquila |

The cycle is located in the upper part of the walls and starts on the east wall, where the months of January and February are depicted. April, May, June are depicted on the southern wall, July and August on the western wall, and finally September, October, November and December on the northern wall. The month of March has been lost. On the short sides are two large windows that illuminate the room. A certain spatial illusionism is sought through architectural framing, with the presence of twisted columns dividing the scenes. The red and white frilled curtains are not coeval to the cycle, but made in the 16th-century restoration carried out by Marcello Fogolino at the behest of Bishop Bernardo Clesio: other repainting was also done on that occasion. The painter of this cycle seeks spatial continuity between the various scenes through certain expedients. For example, a lady slides her arm around a small column ideally connecting two months. Attention to detail and spatial ambiguity coexist, as there is no respect for actual proportions.

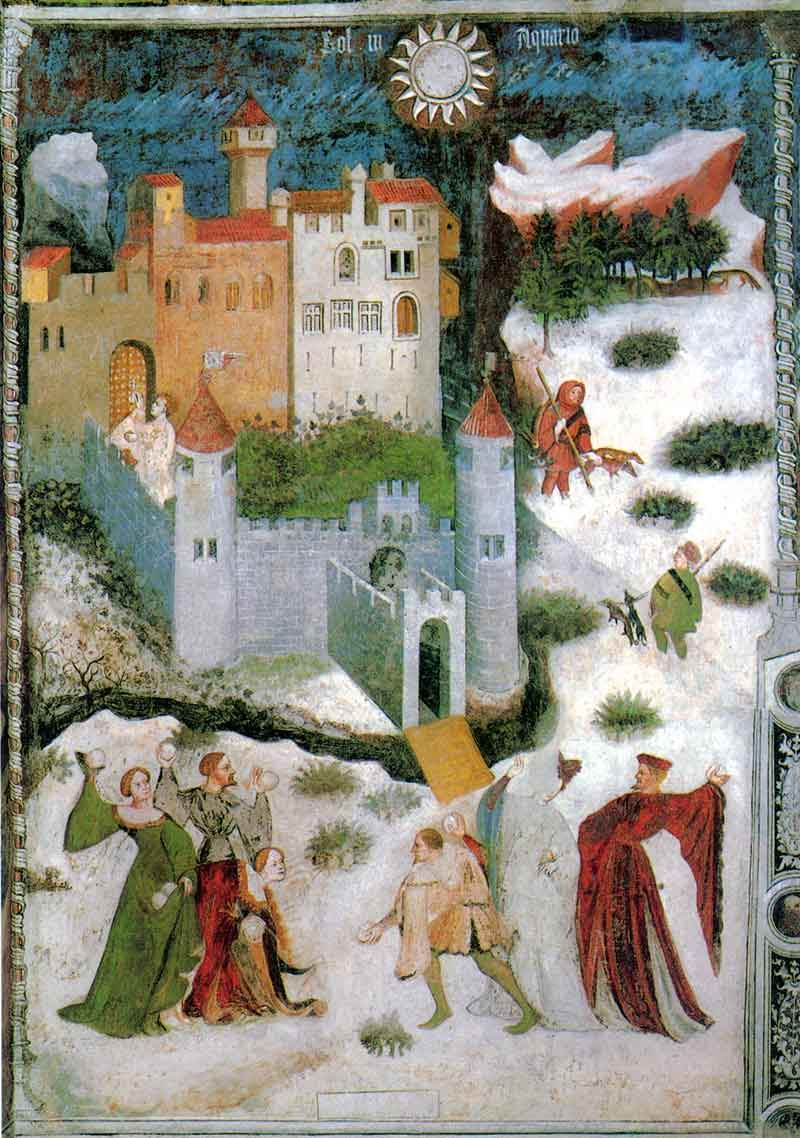

January is presented with a snowy landscape, the first in Western painting that has come down to us intact. In the foreground a group of noblemen amuse themselves by throwing snowballs. In the background is depicted, with great attention to detail, a castle. Art historian Niccolò Rasmo identified it with that of Stenico, which was restored by George of Liechtenstein himself, whose insignia soars over the front towers. On the right, in reduced size, are two hunters with dogs, while in the distance in a fir forest two foxes can be spotted. In the background, the mountain, a constant element in this cycle, is depicted. Vegetation is reproduced in a timely manner: in addition to fir trees, ivy, strangely not snow-covered, can be recognized in the castle garden.

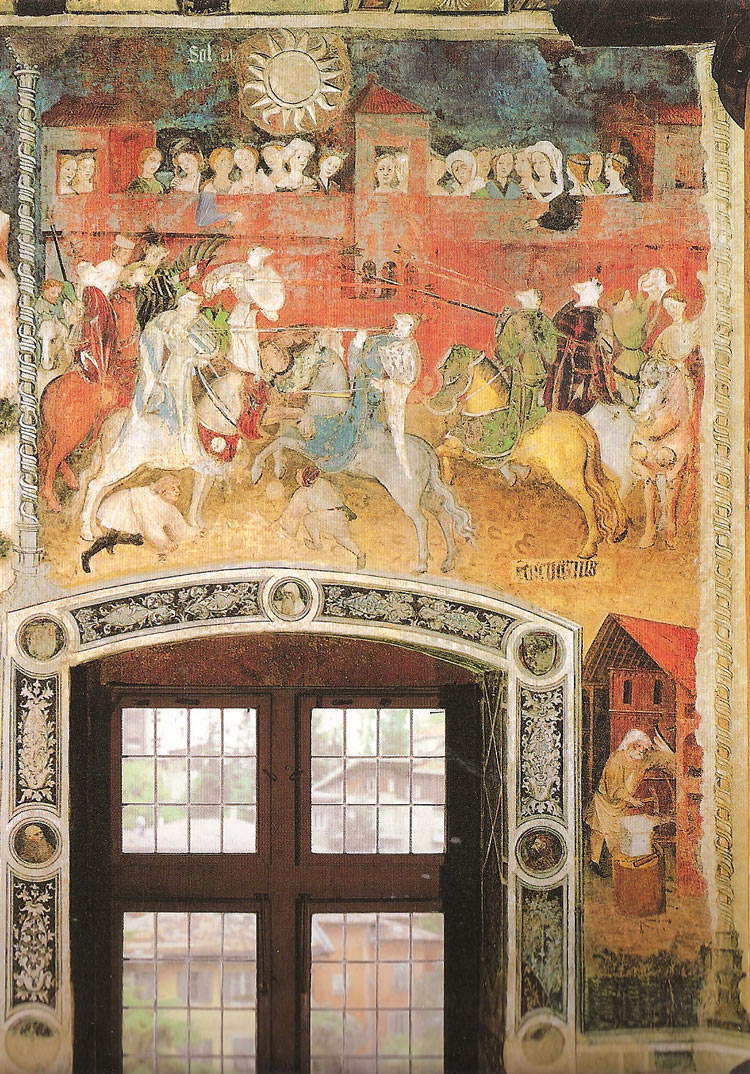

February occupies the available area above and to the right of the eastern window. In the upper area, a medieval joust is depicted: while knights compete, ladies watch from the castle walls, with iconography typical of certain French ivory covers. The lower right area depicts a blacksmith inside his workshop. The spatial incongruity of the building that houses him can be seen, such as the cupboard in which the tools of the trade are stored presented in the foreground.

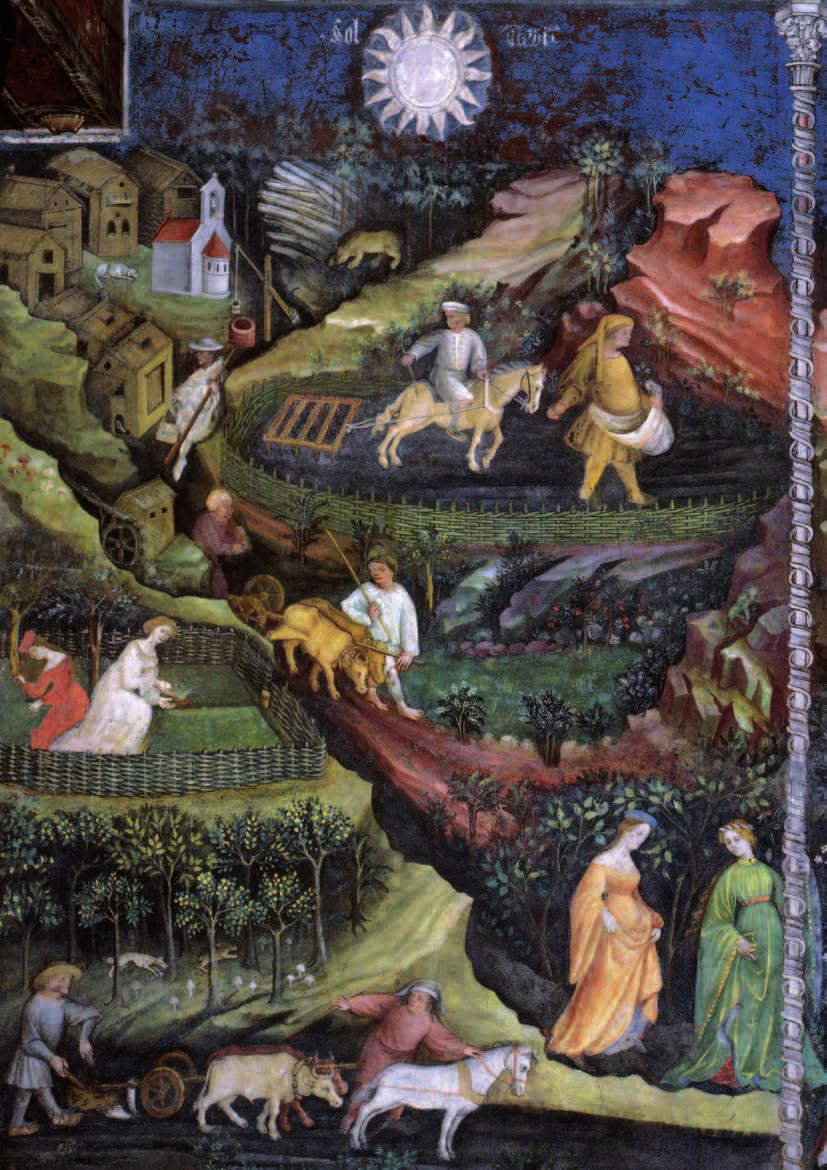

A very rich and varied depiction is chosen for the month of April, in a landscape that features forests, rocks, meadows and plowed land. Peasant activities prevail over courtly ones. In the lower area, beyond the fence that begins in February and ends here, the plowing of fields takes place. On the right, two ladies, painted with larger proportions than the plowing peasants, walk toward the next scene, and one of them, the one wearing a green robe, embraces the column and trespasses with her arm into the month of May, creating an ideal continuity with the next scene. An ox-drawn wagon is returning from the mill. On the upper left, near a village where a church building can be recognized, rests a pilgrim. To the right, other field-related activities, such as planting, are taking place. Finally, a bear can be seen in the middle of a forest.

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of January (1391-1407; fresco; Trento, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of January, detail |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of February (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of April (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

In the month of May we see an explosion of the plant world. There are no peasant activities, only the courtly youths intent on the art of courtship and other amorous attitudes. The backdrop to this is a blooming rose garden: nature blooms, love blossoms. Above left is a fortified town, in which a Gothic-style church with a double tower on the facade stands out. On the left two noble couples are gathered around a table: one of the ladies is washing her hands in a fountain that has a conspicuous crack in the masonry.

The upper part of June is occupied by a walled city framed with a perspective from below. Two figures of nobles, one male and one female, pass through the city gates, carrying precious objects in their hands, and are accompanied by two dogs, one of which has just freed itself from its chain. On the upper right, near huts used during mountain pasturing, some women are engaged in livestock-related activities, such as milking cattle and making butter and cheese. Two dogs sniff some partridges in the woods. In the lower area, the rose garden from the previous month is still present: here five pairs of noblemen are probably engaged in a dance, accompanied by some musicians who were repainted in Fogolino’s 16th-century intervention. Lilies have bloomed on the lawn.

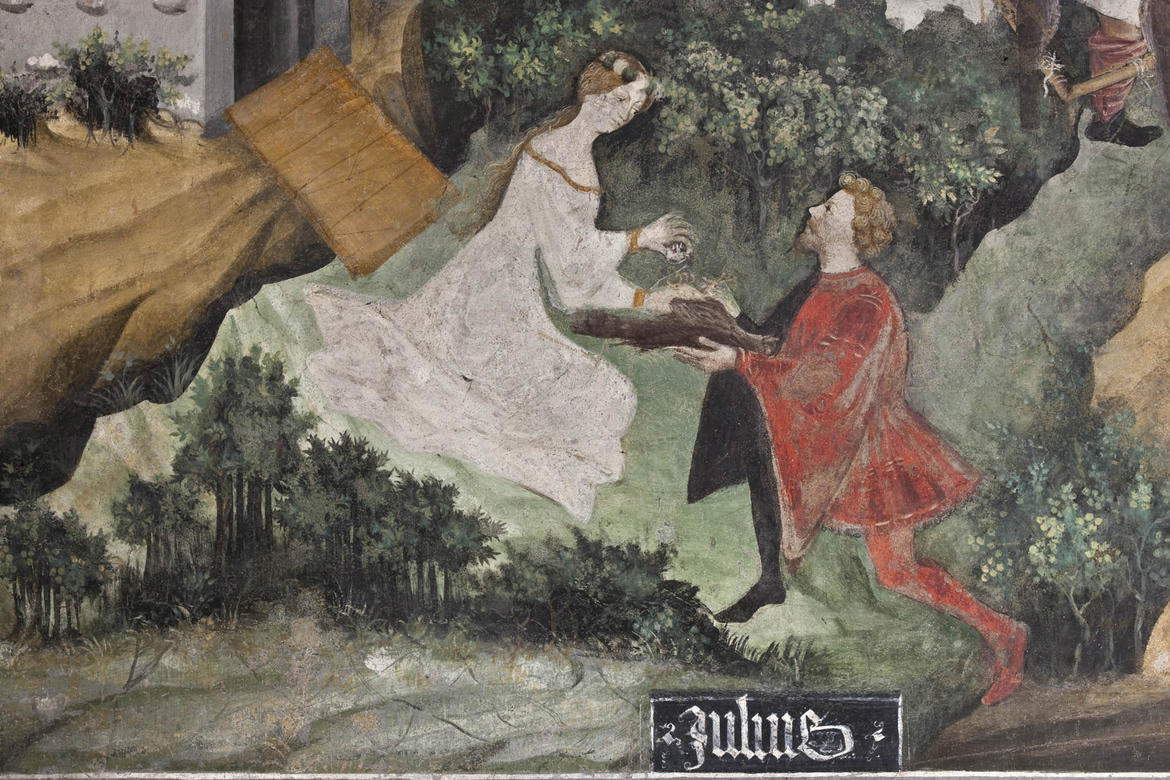

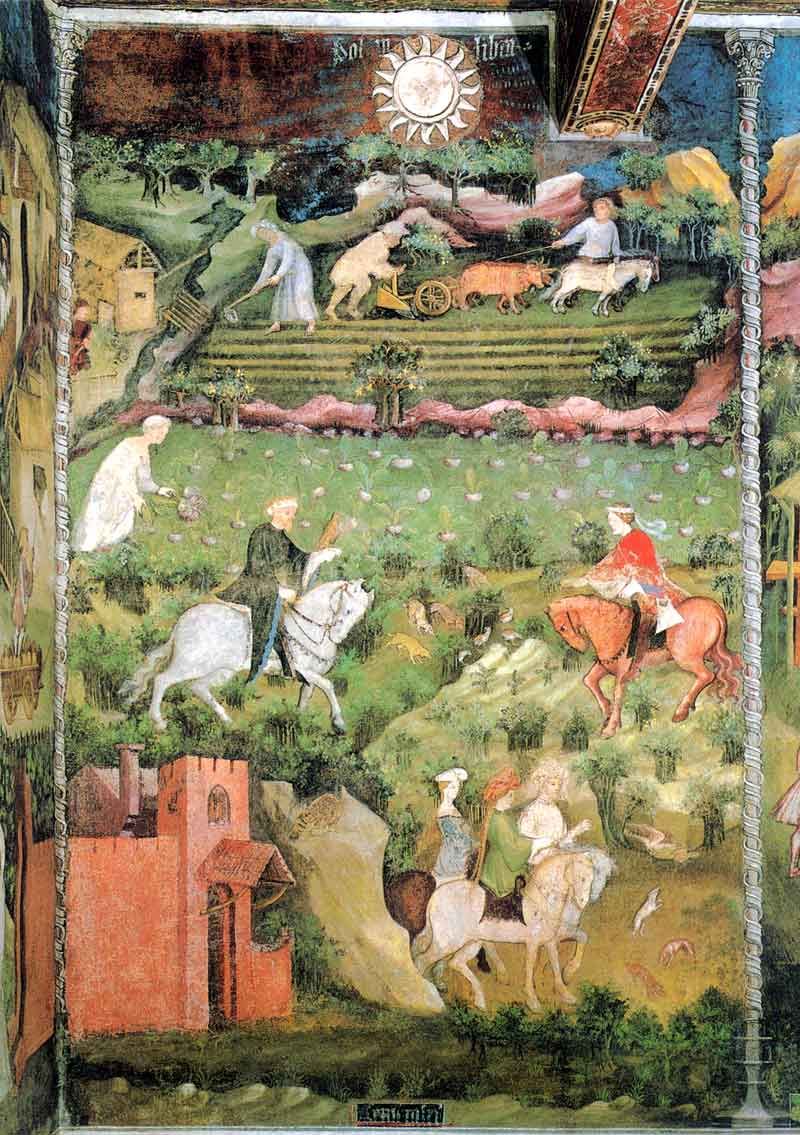

Humble activities prevail in July. Only in the lower area is a moment of courtly life depicted with the offering of a falcon. Related to this practice, a number of falconers carrying falcons on perches are identified within the scene, as described in Emperor Frederick II of Swabia’s De arte venandi cum avibus . In the center of the composition is a lake with a fishing boat, while in the upper part the cutting of hay is illustrated. Once again the care taken in depicting the tools used according to the activity being carried out is astonishing. Near some of the dwellings like those seen in May, a farmer sharpens a scythe, and concluding the composition at the top are mountains depicted as large boulders of different colors. Again, in the upper right is a ruined tower, and there are two other buildings in this scene: a small castle in red on the right and a fortified town on the left. Nature encroaches between these two months, without creating separation.

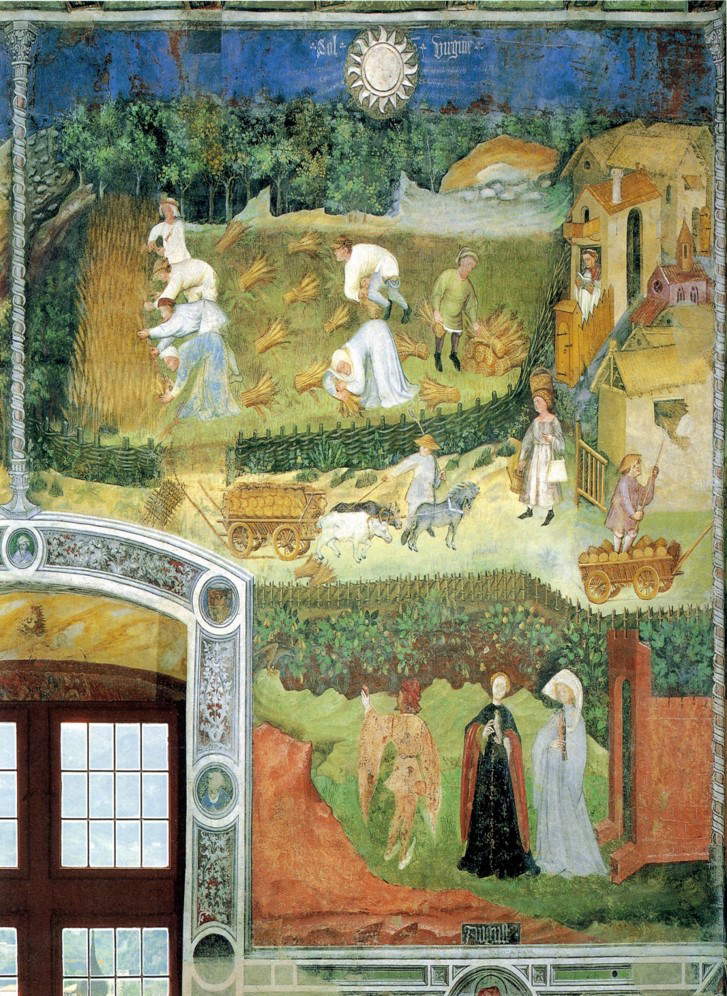

August, like July, is characterized by work in the fields. The composition is wide-ranging, and again the courtly presence is linked to falconry activity, in the lower area. It is the harvesting and arrangement of grain, on the other hand, that characterize the upper part. The road, traveled by a cart loaded with grain pulled by oxen and a horse, leads to the peasant village, where the church and the priest’s house stand out among the buildings.

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of May (1391-1407; fresco; Trento, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of May, detail |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of June (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Buonconsiglio Castle, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of July (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of July, detail |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of August (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of August, detail |

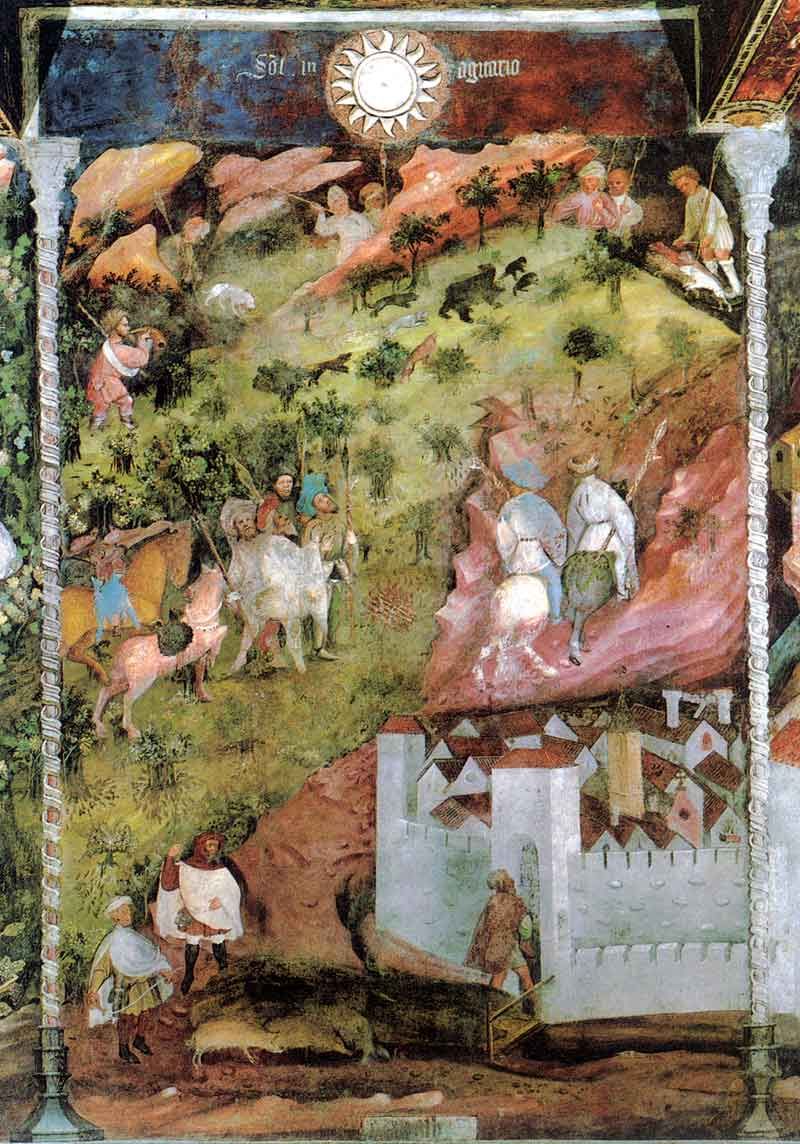

In September the relationship between courtly and peasant scenes is more balanced. Also in this month we find the practice of hunting with hawks, which in fact unites the summer months. A peasant woman harvests turnips in one field, while others are intent on plowing another. The continuity between the months of August and September is carried on by the peasant village at the top and the castle at the bottom. The theme of dogs sniffing for partridges returns, and the nature of the upper area continues into the next month.

October is the month of grape-related activities: harvesting, crushing, preparation of must. Great space is given to the description of tools for harvesting and processing grapes: in particular, the winepress is described in great detail. Both peasants and nobles are involved, each with their own task, in the grape harvest. From the point of view of artistic technique, of note is the use of a stencil to reproduce vine leaves, always the same in shape but varied in color. High up in the mountains, a now-empty mountain pasture hut can be seen.

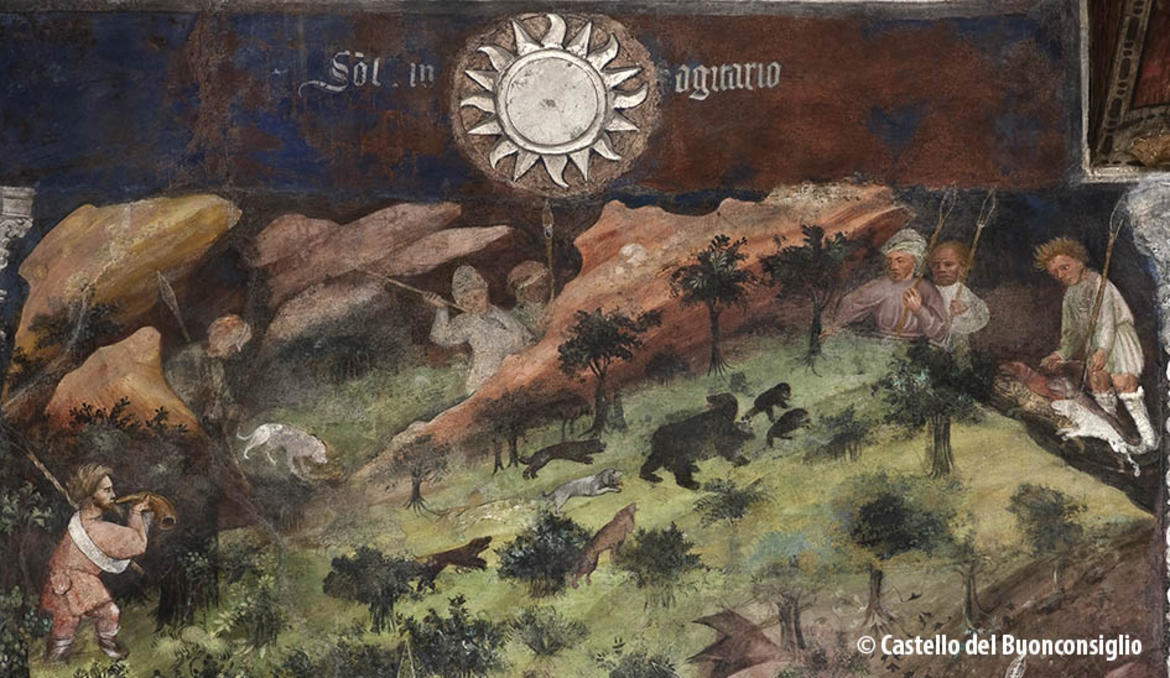

The spatial continuity between the months of November and December is clearly evident: in fact, the town depicted in the lower area is divided by the column but extends into the following month. In November, the countryside prepares to return to the city to face winter: we understand this from the pig farmers who bring their livestock inside the walls. A bear hunt is underway in the mountains, and a few hunters are warming up around the fire. The vegetation becomes sparse and less lush.

Finally, December. The main activity depicted is the cutting of wood, which is then transported on wagons within the town. It has been hypothesized that Trento is represented here and the castle present is actually that of Buonconsiglio, characterized by its tall circular tower. Through some white brush strokes ice stalactites are depicted, and just outside the city walls a water mill is in operation. Men and animals enter and leave through the city gates, indicating how close the relationship between the city and the surrounding area was.

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of September (1391-1407; fresco; Trento, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of October (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Buonconsiglio Castle, Eagle Tower) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of November (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of November, detail |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of December (1391-1407; fresco; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Torre Aquila) |

|

| Magister Wenceslas, Month of January, detail |

There is no documentation that provides a precise name for the author of this cycle. The attribution has settled on the name of Magister Wenceslas, a painter of probable Bohemian origin. His name appears as the painter of the bishop of Trent in the book of the confraternity of St. Christopher at the Arlberg. As far as dating is concerned, one can fix his settlement in Trent as prince-bishop of George of Liechtenstein as the term post quem (1391) and as ante quem the year in which he was imprisoned (1407).

Several artistic cultures are identified within the Torre Aquila cycle, among which the Lombard one stands out. The frames of the months in fact stand in fruitful relation to the Lombard reproduction of the Tacuina sanitatis, a work compiled in Baghdad in the 11th century by the physician Ibn Butlan. They are medical almanacs in which the properties of herbs, vegetables, foods, spices but also behaviors and feelings are described, with the aim of pointing the reader to a correct way of life: they were widely circulated especially in northern Italy in the form of illuminated manuscripts.

Miniatures occupied a large part of the page surface: the subject of the item described is depicted with great vividness and accuracy within a larger context, such as scenes of domestic life or work. One of these specimens was in the library of George of Liechtenstein (today it is preserved in Vienna), so the executor of the cycle of months may have had the opportunity to consult it. Another artistic component that can be discerned is that ofFrench art, particularly in the iconography of courtly themes, and in the general composition that is in dialogue with that of the tapestries. Another parallel can be found precisely in the typology of the painted room: it is an idea that finds comparison with the Pope’s Wardrobe Room in Avignon dated 1343. Finally, one can recognize the artist’s probable artistic culture of origin, namely the Bohemian one, particularly with miniatures, although their refinement is mitigated here by the Lombard component. Instead, stringent comparisons are found with the miniatures of the Wenceslas IV Bible preserved in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. The author of the Trent months cycle brings together different artistic cultures by juxtaposing them in a cycle that has become a valuable visual document of peasant and courtly life at the end of the 14th century.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.