When one thinks of Bari , the association with the patron saint, Nicholas, among the most revered saints depicted in painting, is inevitable. Those who access the old city from the sea are confronted by the cubic bulk of the presbytery area of the Nicolaean basilica (fig. 1), which rises beyond the wall, now a path dedicated to the promenade, but until the early 20th century a watershed between the city and the sea, which lapped it. One has to think that in the Middle Ages such a view must have been highly suggestive and must have moved those, sailors and pilgrims, who arrived in or departed from Bari.

|

| 1. Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas. Ph. Credit Berthold Werner |

Sources.

According to the account in Michael the Archimandrite ’s Life of St. Nicholas (Cioffari 1987, p. 22), penned in the 8th century, Nicholas was born in Patara, one of the major cities of Lycia, in the southwestern part of Turkey, around 255 A.D.; elected bishop of Myra (present-day Demre), he attended the Council of Nicaea (325), dying there a few days later. The saint became “Bari” by adoption beginning in 1087, following the translation of the relics at the hands of sixty-two sailors who, with three caravels, brought the sacred remains to the present-day Apulian capital (Lavermicocca 1987, p. 12). The causes that prompted the sailors to carry out this theft were of various kinds, divine and practical. According to the Legend of Kiev, in which direct testimonies linked to the enterprise are said to have converged, Nicholas appeared in a dream to a priest from Bari, confessing to him that he no longer liked to remain in a place desecrated by the Turks, a thesis also reiterated by the Frankish Compiler, according to which God revealed to a monk his willingness to transfer Nicholas’ relics to the city that was the seat of the Byzantine Catepanate. Various rulers and influential figures tried, but in vain, to steal the relics, while the people of Bari succeeded because that was Nicholas’s will (Corsi 1987, p. 44), playing ahead of the Venetians, who were also interested in grabbing the sacred booty, which, inevitably, would have given greater prestige to their city, with all the socio-econical consequences that would have ensued. The Venetians, in fact, between 1099 and 1100 completed the work of the Barians by cleaning out the tomb of the few remaining bones of Nicholas in Myra; transported to Venice, they are still venerated in the church of St. Nicholas on Lido.

Myra, along with Antioch, Constantinople and Alexandria in Egypt, was among the favored and most heavily traveled destinations of the Bari trade routes. After trying, but in vain, to bribe the Myra clergy and the guardians of the saint’s tomb, the sailors managed to get hold of Nicholas’ skull and long bones and sailed from the port of Myra on the evening of April 20 and landed in that of Bari on May 9, 1087, a Sunday that would become memorable (Lavermicocca 1987, p. 14). With the favor of the people, the relics were entrusted to Elias, abbot of the monastery of St. Benedict; Bari already possessed a cathedral, but Archbishop Ursone granted Elias the task of overseeing the work on the basilica that would house the sacred relics, whose crypt was consecrated as early as October 1089 by Pope Urban II, while Elias was consecrated archbishop of Bari.

The narrative of the events is very detailed in the Tractatus de translatione sancti Nicolai confessoris et episcopi, written in 1087, or at the latest in the following year, by Nicephorus, a clericus probably a Benedictine, and in the Translatio sancti Nicolai episcopi ex Myra by John Archdeacon, both of Bari origin (Corsi 1987, p. 37). While Nicephorus was engaged by the city’s nobles, Giovanni Arcidiacono, among Ursone’s close associates, extolled the religious dimension that had come with the arrival of the relics in the Apulian capital. From then on, Bari became a privileged destination for pilgrims, a common stop for travelers heading by sea or land to the East and, vice versa, to the West, while Nicholas had risen to the status of patron saint of sailors and mariners and ecumenical saint, an attempt pursued by Urban II himself, who, in 1089, had tried to create the conditions for recomposing the unity between the Eastern and Western Churches, drastically interrupted with the Schism of 1054 (Otranto 1987, p. 68).

The true effigies

Theiconography of St. Nicholas as a praying man was fixed between the fourth and sixth centuries, while only later did the image of the full-length saint, portrayed with the Gospel Book and in the act of blessing, emerge; To the latter model seems to refer the oldest icon depicting the saint and preserved at the monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, dated between the 7th and 8th centuries (Lavermicocca 1987, p. 20): Nicholas is portrayed between Saints Peter, Paul and John Chrysostom (fig. 2).

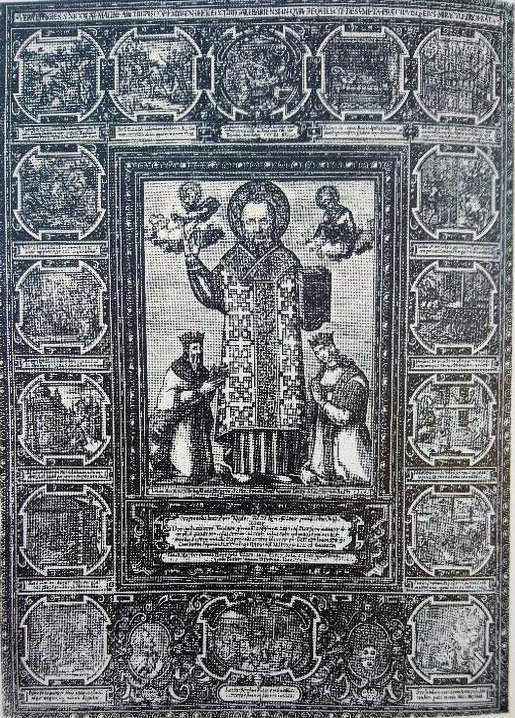

In the Bari basilica, like that of Myra, the relics were arranged under the floor, surmounted by a large icon, which, in its present state, is the one donated in 1319 by Uroš Milutin, ruler of Serbia (fig. 3), on which an engraving was modeled (fig. 4) for the nobleman Domenico Danesio Poliziano by the Dalmatian Natalij Bonifatius in Rome in 1584, becoming an inescapable image for many Nicolaean reproductions: saint Nicholas is portrayed full-length, holding the Gospel with his left hand and raising his right arm pointing to Christ, portrayed half-length at the saint’s face level, on a par with, but on the opposite side of, his mother Mary. At the feet, however, are kneeling in a prayerful attitude Uroš Milutin and his wife Simonida (Calò Mariani 1987, pp. 98-137). The Serbian icon, therefore, became the most venerated image of St. Nicholas, so much so that it was reproduced in canvases, engravings, ex-votos, and small bottles containing the “holy manna,” a substance that exudes from the sacred relic and is collected every year. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, the effigy of the sovereigns was preferred to depict images related to the saint’s miracles, with the appearance of the young cupbearer Adeodato and the miracle of the three children, who, torn to pieces and salted by an unscrupulous innkeeper, were resurrected by St. Nicholas (Calò Mariani 1987, p. 108).

| 2. Icon with Saints Paul, Peter, Nicholas and John Chrysostom (7th-8th century; Sinai, Monastery of St. Catherine of Alexandria) |

| 3. Serbian icon of St. Nicholas with portraits of the donors, King Uroš Milutin and Simonida (1319; Bari, Basilica of St. Nicholas, crypt) |

|

| 4. Natalij Bonifatius, Replica of the True Effigies of St. Nicholas (1584; engraving; Paris, National Library) |

The development of Nicolaean iconography.

In Apulia , iconographic development was accompanied by the proliferation of cult buildings dedicated to St. Nicholas (Sant’Agata di Puglia, Gravina in Puglia, Mola di Bari) or villages named after the thaumaturge saint (think, for example, of the present-day town of Sannicola, not far from Gallipoli).

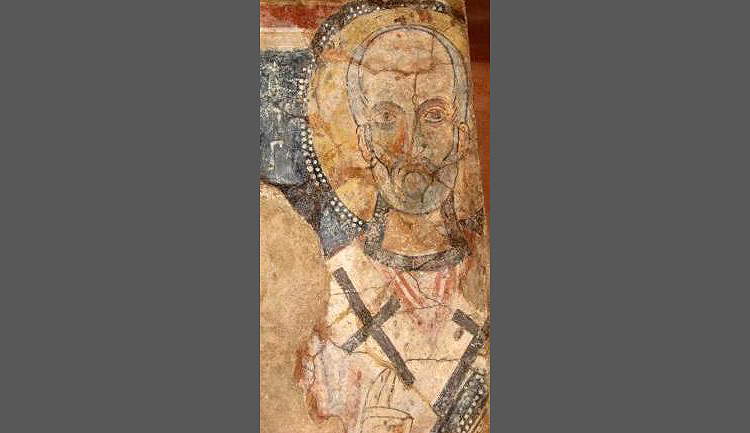

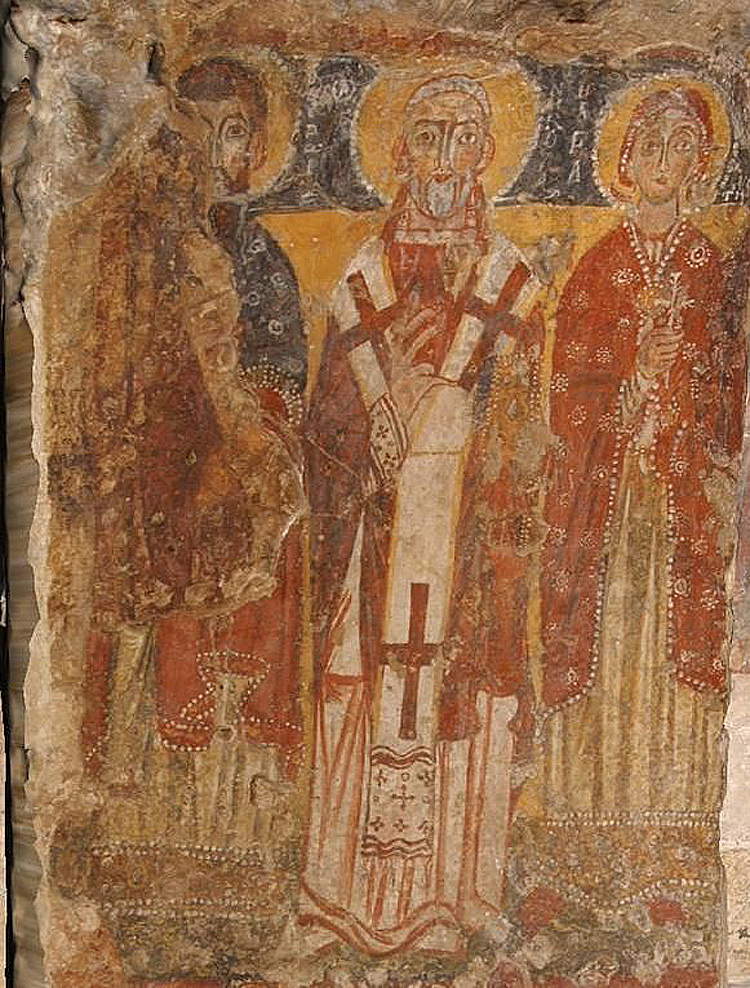

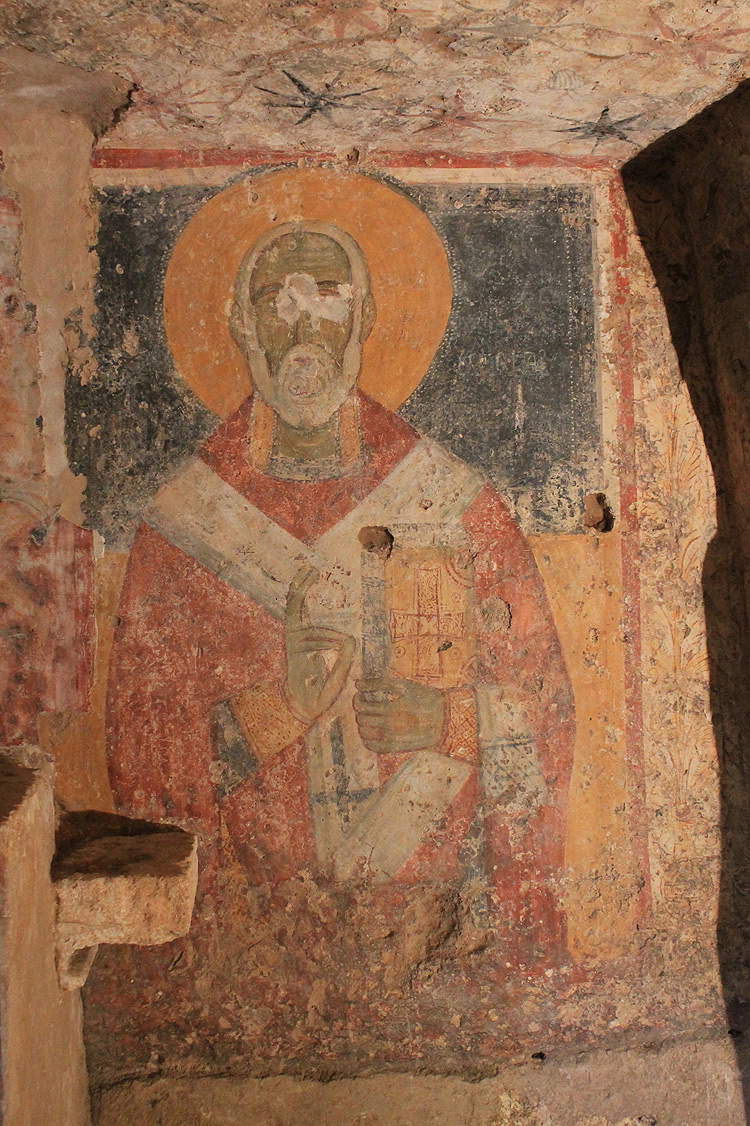

As a result of the traslatio, therefore, there was an increase in the number of Nicolaean images; from the 11th century onward, St. Nicholas appears mainly inside cave churches, as happens in the crypt of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Poggiardo (fig. 5), in Salento, from the late 11th century, where St. Nicholas flanks the Virgin Odegitria in a diptych offered by the commissioners of the fresco, Leo and his wife (Milella Lovecchio 1987, p. 81) or, again, in the crypt of St. Nicholas near Mottola, in the Taranto area, where the effigy of the thaumaturge saint was commissioned by the priest Sarulo. These are cases in which the saint is portrayed mostly holosome, that is, full-length (in addition to the cases mentioned, those in the crypt of Saints Marina and Christina in Carpignano (fig. 6), in which St. Nicholas appears in a 9th-century fresco and in a second of the 11th between St. Theodore and St. Christina are noteworthy-Jacob 1983-84, pp. 103-123; Falla Castelfranchi 2004, pp. 207-221 - , of the crypt of San Biagio in San Vito dei Normanni (fig. 7), in the Brindisi area, or, in sub divo ( “under the sky,” outdoor) cult buildings in the church of Santa Marina in Muro Leccese and, finally, in the crypt of Santa Lucia in Brindisi).

As a half-length, St. Nicholas can be found in the Candlemas crypt in Massafra, datable between the 13th and 14th centuries, in the crypt of the Crucifix in Ugento (fig. 8) and in the crypt of the Coelimanna in Supersano, both from the mid-14th century. In all these cases the paintings are influenced by Byzantine artistic models, with figures lacking depth, strongly flattened and frontal, while from a formal point of view the proportions of St. Nicholas are always enlarged compared to those of the other saints, almost certainly to emphasize the privileged position accorded to the thaumaturge saint.

The iconography of the saint, then, is codified as early as the 11th century, easily recognizable because the bishop wears the phailonion (the cloak down to the ankles), the stichàrion (the tunic) and thehomophorion (the sash that goes around the neck and falls over the shoulders) in the shape of a crocesignate V. The face is usually that of a middle-aged, balding man with a high, wrinkled forehead and a short, curly beard. These are iconographic elements that had a codification that led them to be repeated in the same manner in the East as much as in the West; thanks to the occurrence of historical events of considerable magnitude such as the fall of Jerusalem (1187), the conquest of Byzantium (1204) and the coeval Venetian expansion along the Adriatic and the eastern Mediterranean, the conditions were created for a change of course, with a process of Westernization that invested the lands on the opposite shore from that of Apulia. Thanks to the increasingly sensitive dissemination of cultic products (such as manuscripts and icons) and the physical movement of craftsmen from one place to another, the formal and iconographic features already identified in earlier centuries can be seen in the images of St. Nicholas in later centuries. In the 13th century, moreover, the development of depictions dedicated to the saint of Myra continued in both rocky and subdivisional contexts, in which strongly devotional and didactic representations were made. St. Nicholas appears in the company of the Virgin or other saints: the best example is provided by the frescoes in the crypt of San Vito vecchio in Gravina in Puglia (fig. 9), dating from between the second half of the 13th and early 14th centuries, detached and preserved in the Pomarici Museum in the same city. Portrayed below small arches, St. Nicholas holds a crosier of the spiral type, a Western variant replacing the usual Gospel attribute in coeval Eastern images.

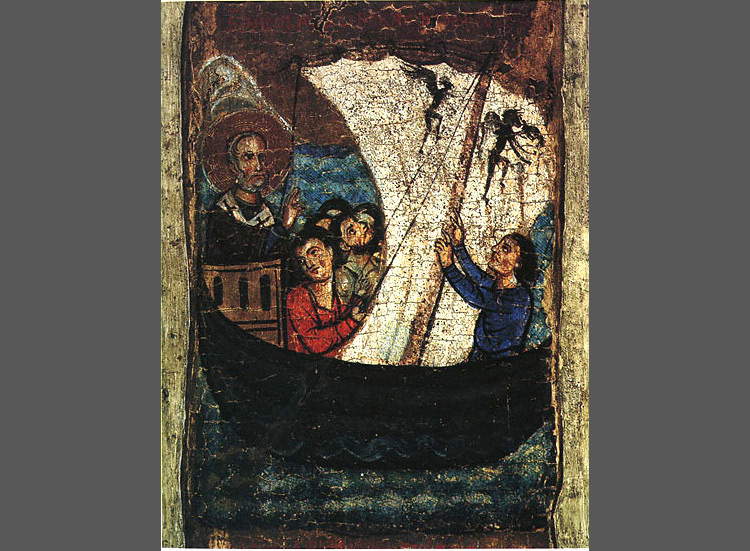

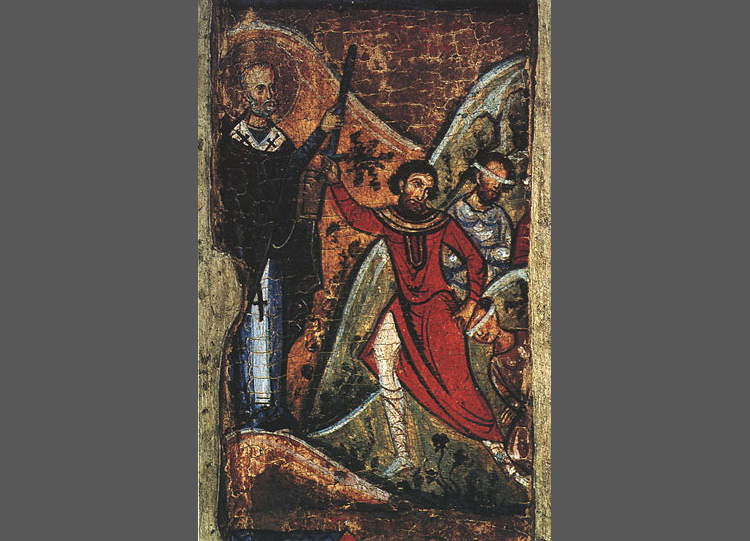

At the same rate, hagiographic icons developed between the 12th and 13th centuries, with the saint portrayed as an interior figure and all around scenes from his life; the most important example is the icon dating from the second half of the 13th century (fig. 10), kept at the Pinacoteca Provinciale “Corrado Giaquinto” in Bari, but coming from the medieval church of Santa Margherita in Bisceglie, built by the Falcone family in 1197, for which critics have identified stringent similarities with works from the Holy Land, but especially with the 12th-century icon of St. Nicholas and stories from his life (fig. 11) kept in the monastery of St. Catherine of Alexandria on Mount Sinai. In the Bari panel St. Nicholas is portrayed full-length, wearing bishop’s robes; he clasps the Gospel with his left arm and raises the other in a blessing sign. At face level, half-length, Christ and the Virgin are portrayed, left and right respectively, handing him the book andhomophorion. All around, however, are distributed scenes from Nicholas’ life, recognizable with the help of Latin inscriptions inscribed at the top of the panels; starting from the first register on the left are the Miracle of the Bath, theEducation in the Christian faith, the famous episode of the dowry given to three maidens, the Thanksgiving from their father who, lacking money, had induced them into prostitution, theElection as bishop, the Praxis de nautis (the rescue of sailors, fig. 12), the Sortilegio di Artemide, the Salvage of three soldiers by Nicholas from unjust execution (fig. 13), the Praxis de stratelatis (the rescue of three officers at Emperor Constantine’s court following unjust death sentence), Nicholas’s Apparitions in a dream to Constantine and Ablavius, the Thanksgiving of the two stratelatis, and, finally, the miracle of Adeodatus, a young Christian kidnapped by the Saracens with whom he had been employed as a cupbearer (Milella Lovecchio 1987, pp. 122-123).

Among the stories linking the saint to the sea, the Praxis de nautis refers to the voyage by some sailors to Jerusalem, while the Sortilegio di Artemide depicts the moment when the devil, in the guise of a young and dashing woman, approaches some sailors on their way to Myra on pilgrimage in his boat and asks them to bring a flask of oil to be placed on the saint’s tomb. According to accounts in the Latin version of the Life of John the Deacon and in the EncomiumNeophyti, attributable to the 1200s, St. Nicholas is said to have appeared to the sailors on another boat and ordered them to empty the contents of the flask, which, on contact with water, would catch fire. In the Bari panel, the scenes are all set outdoors and their setting harks back to miniature models that the painter, probably local, must have been familiar with, while the distribution seems reminiscent of the same one that makes up the hagiographic icon frescoed in the crypt of St. Nicholas in Mottola or, to remain in the Bari area, the one in the cave of Santa Maria dei Miracoli in Andria (fig. 14), dating from the second half of the 13th century, but incorporated into one of the largest Marian shrines in Apulia, built in the first half of the 17th century. The episodes from the life of St. Nicholas actually arise from interpolation that occurred in the 10th century with those of another saint, Nicholas of Sion, co-founder of the monastery of Holy Sion, not far from Myra, who lived two centuries after St. Nicholas of Myra and died in 564 (Milella Lovecchio 1987, p. 92).

In that period, relations intensified between Apulia, a natural bridge stretching toward the East, and the Holy Land, which became a strong pole of attraction, where conditions were created useful for cultural grafts mixed with Byzantine culture and Western morphemes. In modern times, the late Byzantine paintings of Apulia depended heavily onCretan art, a school that continued to operate until at least 1640 and found in Venice the most stringent term of comparison. Add to this the by no means circumscribed phenomenon of Cretan painters who had set up store in the cities of Otranto, Barletta and, most likely, even Monopoli. Among the major representatives of the Cretan school is Andrea Rico da Candia, active since 1451, to whom we owe the triptych preserved in the Bari basilica depicting Our Lady of the Passion between Saints John the Theologian and Nicholas (fig. 15): the figures are portrayed in half-length, the faces are well turned to match the necks, and Nicholas is most recognizable by thehomophorion, by the now established physiognomic type of the face, and by the gesture, all Byzantine, of joining the left thumb and ring finger to indicate the dual nature of Christ.

Beginning in the first half of the 15th century, a late Gothic style spread, especially in the Terra d’Otranto, which was specifically affected by what came to be delineated in the Umbro-Marchigiana area and which, in Salento, gave really high results thanks to the encounter with the artistic acceptations coming from the Neapolitan capital. St. Nicholas continued to be portrayed below architectures of Gothic intonation, holosome and in the company of other saints, as indicated by the frescoes executed between the second and third decade of the century in the church of Santa Caterina d’Alessandria in Galatina, founded at the behest of Raimondello del Balzo Orsini from 1384 and decorated in fresco and in several times by the feudal lord himself, his wife Maria d’Enghien and their son Giovanni Antonio until the late 15th century, or, again, those made in the church of Santo Stefano in Soleto, also belonging to the powerful feudal family (fig. 16).

In addition to the wall paintings are the polyptychs of the Vivarini workshop, among the most prolific between 1460 and 1483, which from Venice reached the Apulian littorals and then bent inland; among all of them it is worth mentioning the one from Santa Maria delle Grazie in Altamura and currently exhibited in the Pinacoteca Provinciale in Bari (fig. 17).

|

| 5. Saint Nicholas, detail (9th century; Poggiardo, rock church of Santa Maria degli Angeli). |

|

| 6. St. Nicholas between Saints Christina and Theodore (11th century; Carpignano, rock church of Saints Marina and Christina) |

|

| 7. St. Nicholas (San Vito dei Normanni, crypt of San Biagio) |

|

| 8. St. Nicholas (mid-14th century; Ugento, crypt of the Crucifix) |

|

| 9. St. Nicholas (late 13th-early 14th century; Gravina in Puglia, Pomarici Santomasi Museum, former church of San Vito) |

| 10. Hagiographic icon of St. Nicholas and stories from his life (second half 13th century; Bari, Pinacoteca Corrado Giaquinto; formerly Bisceglie, church of Santa Margherita) |

| 11. Hagiographic icon of St. Nicholas and stories from his life, detail (12th century; Sinai, Monastery of St. Catherine of Alexandria) |

|

| 12. Hagiographic icon of St. Nicholas and stories from his life, Praxis de nautis (second half 13th century; Bari, Pinacoteca Corrado Giaquinto; formerly Bisceglie, church of Santa Margherita) |

|

| 13. Hagiographic icon of St. Nicholas and stories from his life, Rescue of three soldiers unjustly condemned to death (second half 13th century; Bari, Pinacoteca Corrado Giaquinto; formerly Bisceglie, church of Santa Margherita) |

| 14. Hagiographic icon with St. Nicholas and stories from his life (mid-13th century; Andria, crypt of Santa Maria dei Miracoli) |

|

| 15. Andrea Rico da Candia, Madonna of the Passion between Saints John the Theologian and Nicholas (1451; Bari, Basilica of San Nicola) |

|

| 16. Saint Nicholas (1420-1430; Soleto, church of Santo Stefano) |

|

| 17. Bartolomeo Vivarini, St. Nicholas, detail of polyptych (c. 1490; Bari, Pinacoteca Corrado Giaquinto; formerly Altamura, church of Santa Maria delle Grazie) |

The iconography of St. Nicholas from the 16th to the 18th century.

During the 16th century there was a greater impetus for the creation of wooden statues and polyptychs, which were increasingly used to complete altars according to the tastes of the local nobility, which, in this case, was a spokesman for a fashion that was widespread almost everywhere in southern Italy. Having reduced the Greek presence to a minimum, those buildings of worship used until then for the Greek rite were modernized, of which the case of the Altamura church of San Nicola is among the most famous cases.

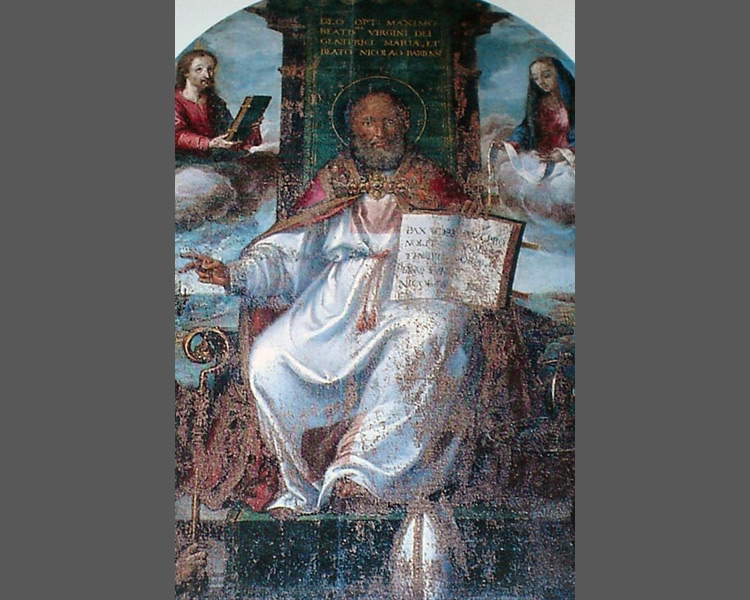

In the same turn of years a new Nicolaean iconography emerged, according to which the holy bishop, clad in sumptuous robes, is seated on a throne: one version is that of Gaspar Hovic (Oudenaarde, 1550 - Bari, 1627), executed around 1581 for the Capuchin church in Corato (fig. 18); in the canvas the usual attributes of the saint, the crosier held by the commissioner of the work, Adeodato, recognizable for holding a tray with a carafe, return punctually by now, while his connection with the sea is emphasized with the view that opens beyond the back of the throne.

Toward the third decade of the century the traditional importation of paintings from Venice wanes as we turn with increasing attention to Naples. St. Nicholas continued to be portrayed alone, but increasingly in the company of other saints and the Virgin: in Sacred Conversations the saint is clad in bishop’s robes, portrayed with the book, on which three golden apples often rest, an allusion to the episode of the three maidens, and in company with the now familiar Adeodatus and the three resurrected children. This iconography remained virtually unchanged over the next two centuries, so much so that the cult of St. Nicholas continued to be among the most celebrated even by the new religious orders, especially the Theatines, about whom we will return. In Barletta Cesare Fracanzano (Bisceglie, 1605 - Barletta, 1652) painted around 1639 the Immaculate Virgin between Saints Joseph and Nicholas of Bari (fig. 19) for the church of St. Anthony, in which he combines the recent cult for St. Joseph, elevated in 1621 by Pope Gregory XV to a universal feast day set for March 19, with the older and more widespread cult for St. Nicholas, both of whom were then united with one of the most heartfelt themes of the Counter-Reformation, the Virgin conceived without blemish, whose dogma was decreed only in 1854 by Pope Pius IX. Around 1651, however, for the church of San Ruggero he painted the monumental altarpiece of St. Nicholas of Bari (fig. 20), in which the bishop is portrayed kneeling, his head slightly turned upward, where two chubby putti are moving, holding his mitre and crosier; struck by the divine light, one of them is forced to shield his sight by raising his right arm (Doronzo 2013, pp. 207-211).

Among the painters close to Cesare Fracanzano was Carlo Rosa (Giovinazzo, 1613 - Bitonto, 1678); both had already worked in the 1640s for the choral painting enterprise in Santa Maria della Sapienza in Naples. After Cesare’s death, Carlo, at the head of the so-called Bottega bitontina, which was very prolific in the Land of Bari, became among the leading representatives of naturalism in many areas of the “periphery” of the Spanish Viceroyalty, as well exemplified by the cycle with Stories from the Life of St. Nicholas and the Virgin for the ceiling and transept of the basilica of St. Nicholas in Bari (fig. 21), executed between 1661 and 1662 and again between 1666 and 1668 (Pugliese 1987, pp. 80-90; Melchiorre 2000, pp. 308-315), or the one with Stories from the Life of St. Nicholas for the ceiling of the nave of San Gaetano in Bitonto (fig. 22), from 1665, kept by the Teatini who, as already anticipated, celebrated the holy bishop by entrusting Carlo Rosa with the decoration of the ceiling of their house (fig. 23, Basile Bonsante 1994, pp. 527-568).

For the Bari basilica, the work of carving the ceiling was assigned to Caterino Casavecchia from Matera and Michele Maurizio from Naples, who was already engaged around 1658 in the execution of new backs for the choir stalls in the crypt, while that of gilding to Cesare Villano. The work was carried out thanks to the many revenues raised as a result of the averted plague of 1656, in which the Spanish crown, pilgrims and faithful, many originally from Naples, and the viceroy himself Gaspar de Bracamonte, count of Peñaranda, participated, financing the work on the transept ceiling (Pugliese 2000, p. 106).

For the Bari basilica, the use of a wooden ceiling seemed appropriate to conceal, in a period characterized by the church’s strong Baroque modernization, the old architectural structures; the final result is characterized by strong dynamism, to which contribute the continuous variations in shape and size of the canvases set in octagonal, quadrangular, and trapezoidal frames covered in gold and silver, interspersed, in turn, with various plastic figures, carved in the round or in high relief, such as angels, cherubs, busts of saints, and zoomorphic elements. The double-headed eagle, emblem of the Hapsburgs of Spain, to whom southern Italy belonged politically, is juxtaposed with the coats of arms of the Prior, the Basilica Chapter, the City and Province of Bari, and the nobleman De Sangro, in a tight but elegant and never oppressive horror vacui. In the canvases Carlo Rosa seems to be yes linked to the Fracanzan ways, but the results he arrives at are the outcome of a very variegated contaminatio, with high tones, united nevertheless by a’gentler interpretation of color, according to the Flemish innovations spread in Naples in the wake of Antoon van Dyck by Pietro Novelli (Monreale, 1603 - Palermo, 1647) and Andrea Vaccaro (Naples, 1604 - 1670). It is, therefore, an art by which deeds (Nicholas’s participation in the Council of Nicaea and the legendary episode of the slap to Arius, fig. 24) and miracles related to St. Nicholas (the liberation of Adeodatus following his parents’ invocation of the saint, fig. 25), to which other significant messages are juxtaposed, ranging from the founding of the basilica to the exaltation of the new cults linked to the devotio moderna of the Counter-Reformation, such as that for theImmaculate Conception, depicted in the large central canvas of the nave, under which Saint Nicholas is portrayed on a boat commanded by angels (fig. 26). For the transept, Carlo Rosa executed a large octagonal canvas with the image of the Eternal Father, surrounded by eight other canvases depicting the Virgin and saints, interspersed with each other by angel-caryatids. On the four trumpets connecting the arches of the transept of the presbytery area were frescoed the four Evangelists and flying cherubs, partly lost, of which the date 1662 remains as a reminder of the work.

Among the eighteenth-century painters who devoted attention to St. Nicholas was the Molfettese Corrado Giaquinto (Molfetta, 1703 - Naples, 1766): the sketch (fig. 27), autographed, which served as a model for the large altarpiece painted in 1746 for the church of San Nicola de Lorenesi in Rome, later lost, is preserved in the Bari picture gallery. St. Nicholas, in bishop’s robes, solemnly quells a sea storm that threatens to sink a boat full of sailors. The Virgin, portrayed on a bank of clouds in the company of angels, also participates in the miraculous event.

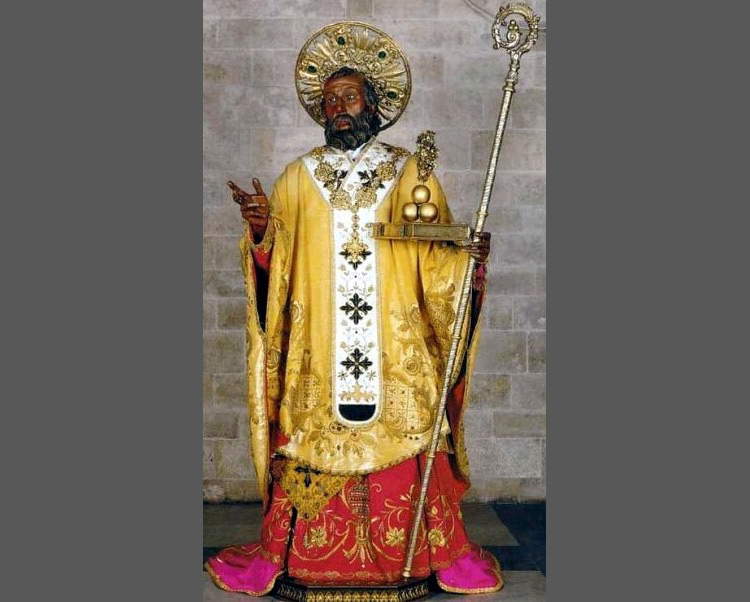

To conclude this iconographic and art-historical excursus on St. Nicholas, mention should be made of the silver altar of the saint dating back to 1684, still in situ in the right side of the presbytery of the Bari basilica, and the statue of the saint (fig. 28) that is carried in procession by sea and land, endlessly reproduced in folkloric studies devoted to St. Nicholas and in devotional holy cards; it went to replace a 17th-century statue preserved today in the nearby church of St. Gregory, overlooking the basilica dedicated to the saint, and was carved in 1794 by Giovanni Corsi, most likely a Neapolitan who had moved to Bari, as can be seen from the inscription engraved on the chest and perhaps trained in the workshop of the more famous sculptor Giacomo Colombo, documented in Naples from 1678 to 1731 (Pasculli Ferrara 1991, pp. 109-117).

|

| 18. Gaspar Hovic, Saint Nicholas Enthroned (1581; oil on canvas; Corato, Church of the Capuchins). |

|

| 19. Cesare Fracanzano, Immaculate Virgin between Saints Joseph and Nicholas of Bari (1639; oil on canvas, 1639; Barletta, church of SantAntonio) |

|

| 20. Cesare Fracanzano, Saint Nicholas (1651; oil on canvas; Barletta, church of San Ruggero) |

|

| 21. Carlo Rosa, Stories from the Life of St. Nicholas and the Virgin (1661-1668; Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas, ceiling, overall view) |

|

| 22. Carlo Rosa, Stories from the Life of St. Nicholas (1665; Bitonto, church of San Gaetano, ceiling, overall view) |

|

| 23. Carlo Rosa, Saint Nicholas between Saints Gaetano and Andrew Avellino (1665; Bitonto, church of San Gaetano) |

|

| 24. Carlo Rosa, St. Nicholas slaps Ario (1661-1668; Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas, ceiling) |

|

| 25. Carlo Rosa, St. Nicholas frees Adeodatus, detail (1661-1668; Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas, ceiling) |

|

| 26. Carlo Rosa, Immaculate Conception and St. Nicholas in a boat piloted by angels (1661-1668; Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas, ceiling) |

|

| 27. Corrado Giaquinto, St. Nicholas Saves the Shipwrecked (ante 1746; oil on canvas; Bari, Pinacoteca Corrado Giaquinto) |

|

| 28. Giovanni Corsi, statue of St. Nicholas (1794; Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas) |

|

| 29. Giovanni Corsi, statue of St. Nicholas, detail (1794; Bari, basilica of St. Nicholas) |

|

| 30. Bari, procession of St. Nicholas |

The statue of St. Nicholas is properly a clothed mannequin in the sense that the head, hands and feet are wooden, while the body is composed of lighter materials and, therefore, more easily transported during processions. The somatic features of the saint are the same as those presented by the real effigies, with dark epidermis (fig. 29), in deference to the bishop’s Middle Eastern origin, with a receding hairline and a long, dark beard; the hands are carved in such a way that the left can hold the crosier and the right, with bent ring finger and little finger, is in a blessing attitude. Giovanni Corsi’s St. Nicholas, for the past two centuries, has been carried in procession on the morning of May 8 each year through the streets of the old city to the St. Nicholas pier: carried aboard a boat, it ideally continues the procession at sea until the evening, when it is brought back again to the mainland, commemorating the arrival of the sacred relics in 1087. The solemnities begin as early as the afternoon of May 7, when the solemn historical procession called the “Caravel” parades through the streets of Bari (fig. 30) and up to the square in front of the basilica of St. Nicholas, in memory of the boats used by the sixty-two sailors who stole the relics from Myra (Pasculli Ferrara 2017, pp. 363-371). The “Caravel,” preceded by a number of “scenic paintings” in which scenes and miracles of the saint are reproduced, is attended by a very large number of figurants in historical clothing. Arriving near the basilica, the statue of St. Nicholas is handed over by the sailors to the prior and mayor of the city, a moving moment reminiscent of the one during which the wooden box containing the sacred booty (still preserved in the nearby Nicolas Museum) was handed over to Abbot Elias. In a fraternal meeting that unites West and East (remember that St. Nicholas is the most invoked saint in the Balkan countries as far as Russia), the three-day festivity attracts thousands of pilgrims and faithful from all over the world.

Bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.