The crosses of the Museo di San Matteo in Pisa: the world's largest collection of painted crosses

Outside the classic Pisa sightseeing tour that features Piazza dei Miracoli with its Leaning Tower, the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, located on the Lungarno, in Piazza San Matteo in Soarta, in the spaces of theformer Benedictine Monastery of San Matteo, should be an absolute must-see for those visiting the Tuscan city, but also for the Pisans themselves and for students of one of the oldest universities in Italy. In addition to being a point of reference for medieval and Renaissance painting and sculpture including Pisan and Tuscan artists from the 13th to the 15th centuries, the museum holds the world’s most important collection of monumental painted crosses, evidence of one of the high points of the Pisan School in the period between the 11th and 13th centuries and medieval art. Thanks to the commercial, economic, political and cultural power of the Republic of Pisa, from the year 1000 with a culmination in the 13th century a Pisan School developed here that was characterized by a high quality of works and a vivacity that in the same period had no equal in the Italian peninsula. Through the flourishing trade exchanges along the Mediterranean with the East of theByzantine Empire, textiles and other precious goods arrived in Pisa, but art was also influenced by these exchanges, which brought the richness and artistic variety of that world: art of Tuscan tradition thus intertwined with Byzantine art of the Christian religion, introducing novelties in language, techniques and depictions, elevating the Pisan School to one of the most important in the artistic scene of that time. West and East united in the art of a small Tuscan town that became, particularly in the 13th century, a true artistic capital, opening its horizons to the world and the East. A particular example of this openness and fusion between the two worlds and consequently between languages are precisely the monumental painted crosses on display in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa, to which the latter devotes an entire room of the exhibition itinerary.

There are a total of nine monumental painted crosses exhibited in this room, in an elevated and slightly inclined position, and not hung on the walls, but placed by means of supports around the perimeter of the large room, within which the visitor finds himself walking around with his nose in the air in order to admire the various scenes depicted on the imposing crosses. This placement, which inevitably forces one to keep one’s gaze upward at all times, has a precise motivation, since these painted crosses were usually located, in all probability, above the partition that in churches divided the space reserved for the clergy from that reserved for the faithful.

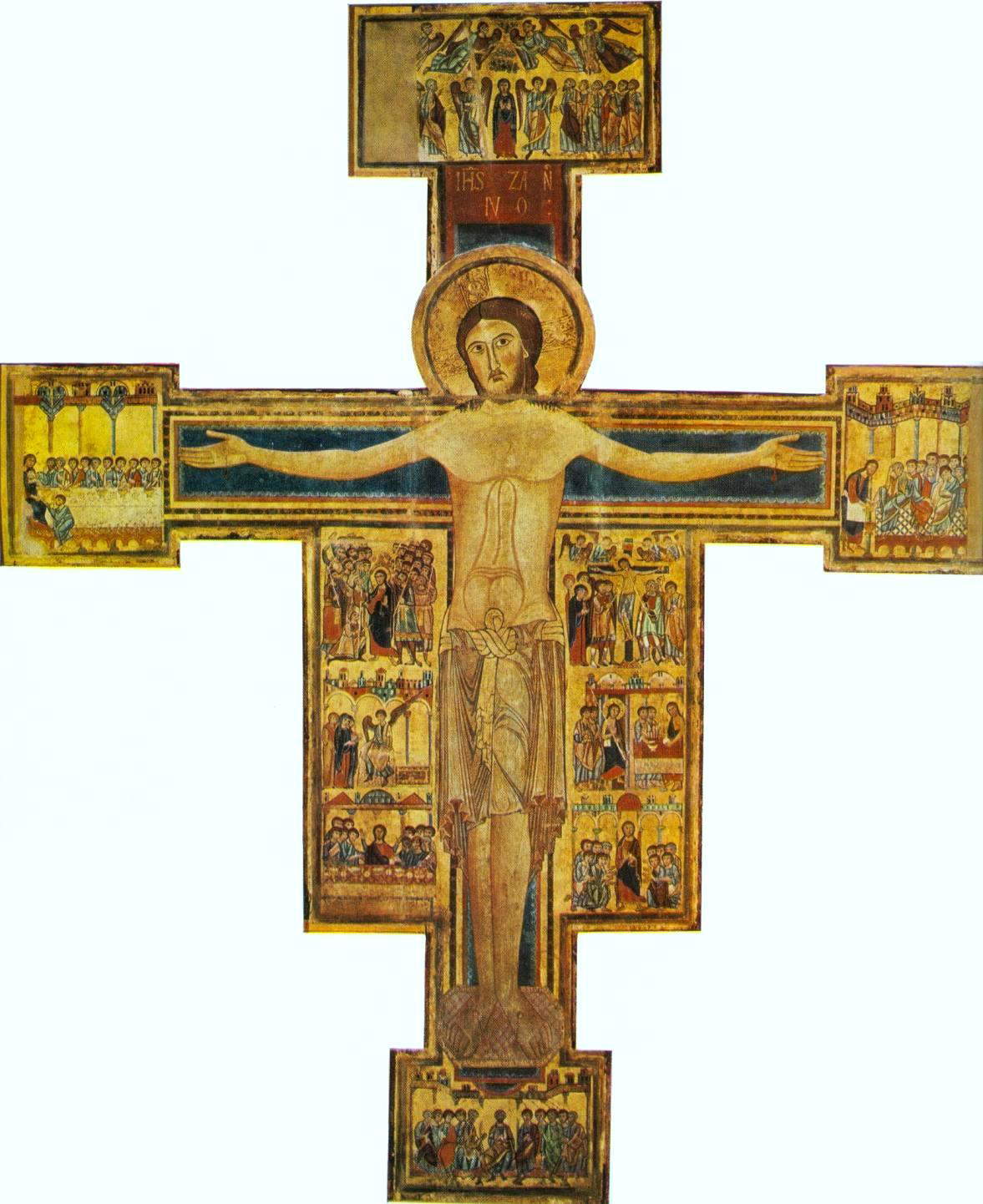

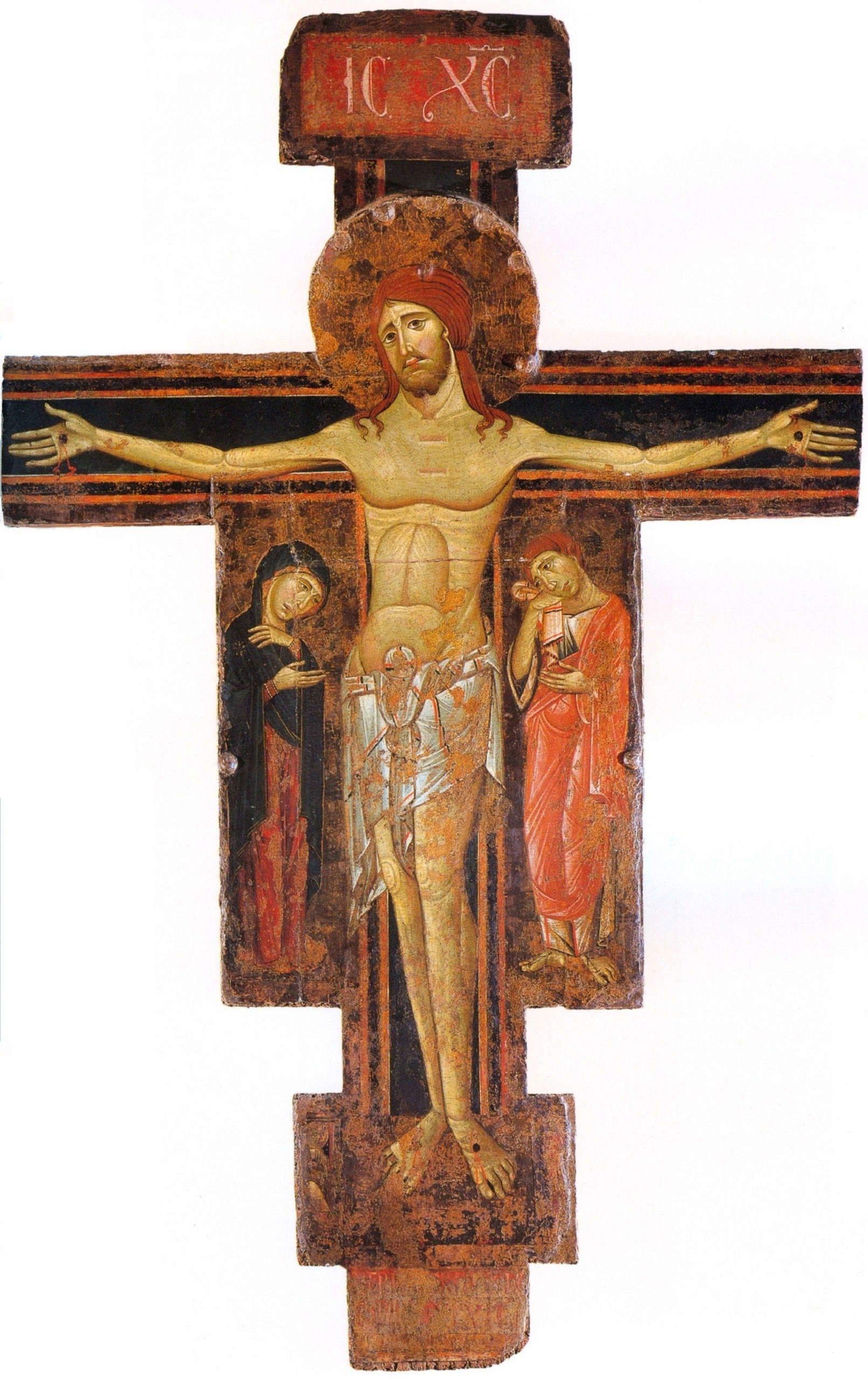

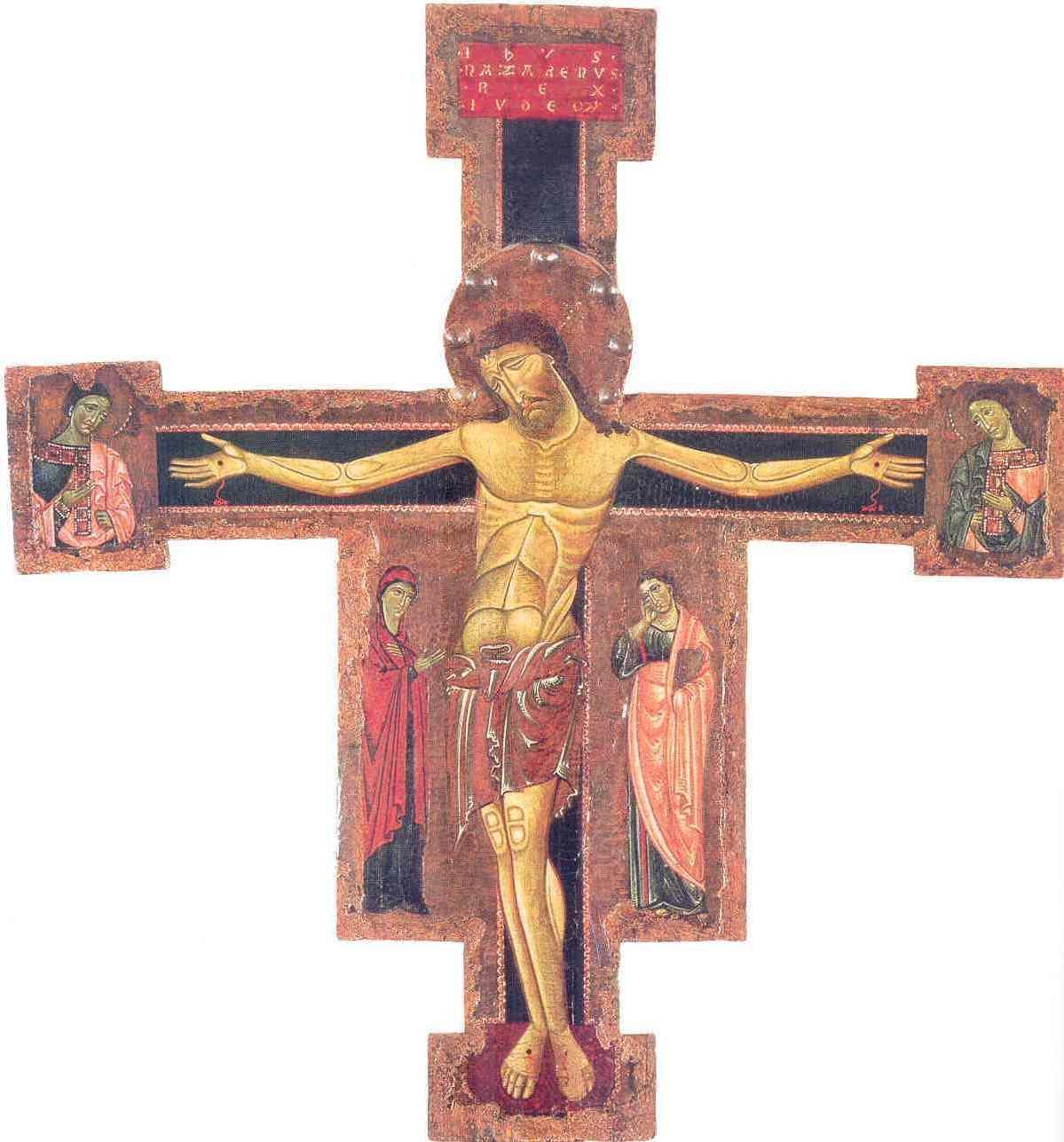

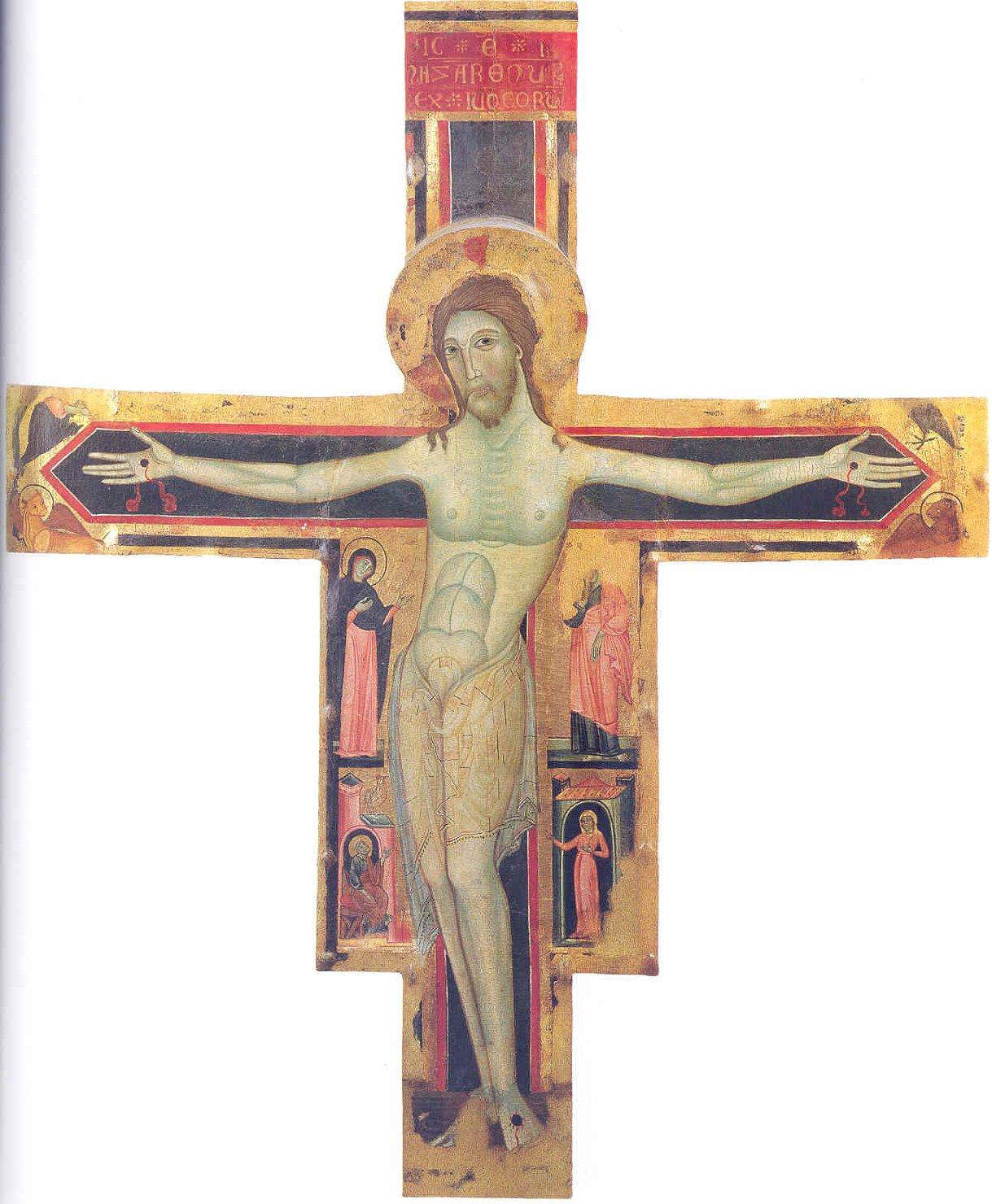

At a time when art had to be as didactic as possible both to tell, especially to the faithful, the sacred stories of the Bible and to teach them the behaviors to follow in order to be a good Christian and thus educate them in the rules of the Christian faith, the crosses with their painted scenes constituted a true poor man’s Bible, since they they narrated to those who went to church (at that time the main gathering place) the episodes of the sacred story, beginning precisely with the Crucifixion, the foundational scene on which the entire Christian religion is based, as a testimony of Christ’s sacrifice for the salvation of humanity. The compositional structure was, as can be seen from the crosses on display, more or less similar: the crucified Christ in the center, with a cymatium and piedychrome at the top and bottom, respectively, depicting scenes from the life of Jesus; the body is flanked by boards showing other scenes, and still others are painted in the terminals, the ends of the horizontal arms of the cross. There are, however, two types of the crucified Christ, both of which can be found in the room of monumental painted crosses: the Christus triumphans and the Christus patiens, literally the triumphant Christ and the sorrowful Christ, depending on which aspect of Christ’s nature one wishes to privilege in the depiction. The former is the divine Christ who triumphs over death and therefore does not suffer on the cross: he is therefore generally depicted with his head erect, his eyes open, an expression that does not presuppose any kind of pain, and with no signs of wounds or blood; the latter, on the other hand, is the human Christ who suffers on the cross and therefore manifests all signs of suffering and pain: His head turned downward, His eyes closed, His body slightly bent, surrendering His weight to one side of the cross, visible wounds at the nails with which He is attached to the cross, and rivulets of blood flowing from the wounds on His hands, feet, and side. This second type of depiction, already used in Byzantine culture, was intended to bring the viewer to a greater participation in Christ’s suffering on the cross, arousing compassion for a more “human” Christ, identification, and of course greater devotion.

Found right here at the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo is the first depiction of Christus patiens on a painted cross: it is the so-called Cross No. 20 made in the late 12th and early 13th centuries by a Pisan-Byzantine painter in tempera and gold on parchment applied to panel and coming from the convent of San Matteo in Pisa. Placed at the end of the room against a blue background (one of only two crosses hanging on a wall), the cross presents in the center the figure of the crucified Jesus, covered by a cloth around the waist, with the characteristics of the mourning Christ, namely, the head reclined on the shoulder, eyes closed, rivulets of blood from the wounds of the hands, feet, and side, and a suffering expression of the face; on the cymatium the resurrected Christ enthroned between four angels and two seraphim, and on the piedychrome the descent to hell. The body is flanked by six panels, three on each side, depicting on the left from top to bottom the Deposition from the Cross, the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, and the Burial of Christ, while on the right from top to bottom the Pious Women at the Tomb with the Angel, the Apparition of Two Disciples and the Supper at Emmaus, and the Incredulity of St. Thomas; in the terminals, the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist on one side and two pious women on the other. It is a work that is influenced by the Byzantine culture that came to Pisa from the East, both in the iconography (probably linked to the Comnenian dynasty) and ornate decoration and in the colors, which are less bright than the Pisan crosses of the 13th century.

Cross No. 20 is juxtaposed by contrast with the cross of the Master of the Cross of the Holy Sepulcher, from the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Pisa and made in tempera and gold on panel in the second half of the 12th century. This one presents the depiction of Christ triumphant with a well erect body, eyes open, no sign of pain on the face, but here thin rivulets of blood gush equally from the wounds. In the six panels of the panel we recognize scenes such as the Mocking of Christ, the Crucifixion, the Pious Women at the Tomb, the Apparition to the Disciples and the Supper in Emmaus, and the Apparition to the Apostles in the Upper Room; on the sides, in the terminals, the Last Supper and the Washing of the Feet, while in the cymatium and piedychrome the Assumption of Mary between angels and apostles and Pentecost. Even older, dating from the early 12th century, however, is the cross from the Church of San Paolo all’Orto in Pisa, made by a Pisan painter and depicting Christus triumphans flanked by four panels with St. John the Evangelist and the Virgin, two pious women, the Descent into Limbo and the Supper in Emmaus. It is one of the oldest painted crosses in Tuscany since it probably dates back to the year 1100, and the typical depiction of the triumphant Christ is remarkable, with his body well erect, eyes large and open, impassive expression and no wounds or blood.

If the left side of the room is completed with the signed cross of Ranieri di Ugolino from the late 13th century from the Spedali di Santa Chiara in Pisa, the right side features the cross of the one who gathered and most of all developed the Byzantine influences by laying the foundations for the later ones of Cimabue and Giotto, namely Giunta Pisano, an artist of the Pisan School who championed the depiction of a “human” Christ, but above all the rules of theFranciscan Order, through which the dramatic image of the sorrowful Christ, closer to man than to the divine, became increasingly widespread. A true masterpiece is the cross from the church of San Ranierino in Pisa that Giunta Pisano made in the mid-13th century and signed on the piedychrome. The painter has reinterpreted here in an extraordinarily expressive and dramatic way the Christus patiens of Byzantine influence: the head and body surrender to death, the suffering suffered is clearly visible on the face, and the complexion is green to indicate mortal lividity. In order to focus the viewer’s gaze on the crucified Christ, he has also eliminated the many sacred scenes and figures that, as we have seen, characterized the painted crosses: instead of the panels on the board, there is only a geometric decoration that serves as a backdrop to the extremely arched body of Jesus; at the top is the bust of the blessing Christ, while in the terminals are the half-busts of the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist. The figures are thus reduced to a minimum precisely to focus all attention on Christ and make the faithful participate in the suffering.

Also on display are two processional crosses painted on both sides: one by Giunta Pisano himself dating from the mid-13th century and coming from the monastery of San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno in Pisa, which, similarly to the cross of San Ranierino, also proposes geometric decoration in the tabernacles and terminals the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist; the other by a Pisan painter follower of Giunta Pisano made in the first half of the 13th century and from the Opera del Duomo in Pisa (the back is better preserved than the front, in which the face of Jesus is no longer visible).

These are then joined by a signed painted cross by Berlinghiero, executed between about 1230 and 1235 and coming from the church of San Salvatore di Fucecchio, and a painted cross by the Master of Castelfiorentino dating from the mid-13th century and coming from the church of San Giovanni dei Fieri in Pisa.

Finally, the museum has three others, not displayed in the dedicated room but in the room immediately following it along with other works of art: they are later, from the last decade of the 13th century to 1320, and are by the hand of the Master of San Torpè (church of Belvedere di Crespina, Pisa), Deodato Orlandi (attributed, from the sacristy of the church of San Francesco in Pisa) and a Tuscan artist (Carceri Giudiziarie).

An important page in the history of Pisa and its ancient art, given by the encounter with another culture, and the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo holds the most significant testimony of this in the world.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.