The Corrado Ricci Fund at the Library of Archaeology and Art History in Rome

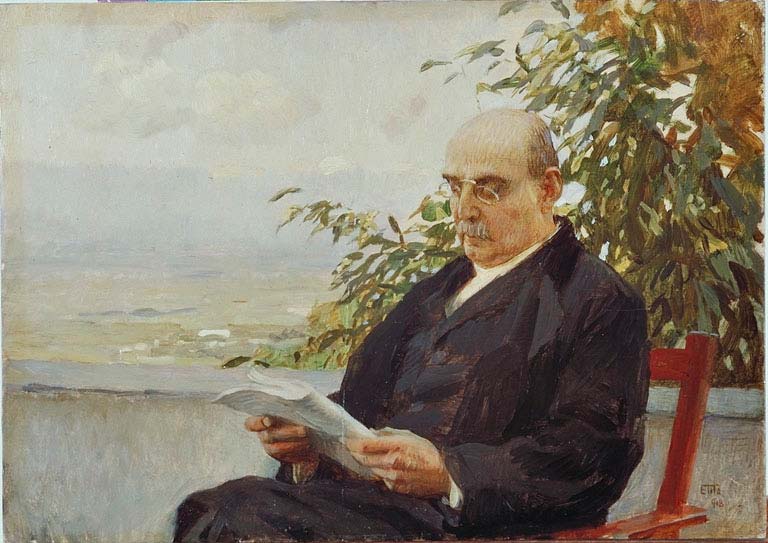

A fund consisting of about three thousand items, including books, prints, photographs and miscellaneous materials: this is the size of the Corrado Ricci Fund of the Library of Archaeology and Art History (BiASA) in Rome, now part of the Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia Institute. It consists of material that belonged to a great scholar of the early 20th century, Corrado Ricci (Ravenna, 1858 - Rome, 1934), who was a distinguished archaeologist and art historian, as well as a four-time senator from the ranks of the National Fascist Party: his adherence to fascism, convinced because Ricci believed it was useful for the realization of his projects, nevertheless weighed on his image, although he nevertheless maintained a certain independence from politics, moreover declaring himself in 1925 an “apolitical animal” (although he was among the signatories of the Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals), and turning his attention exclusively to heritage.

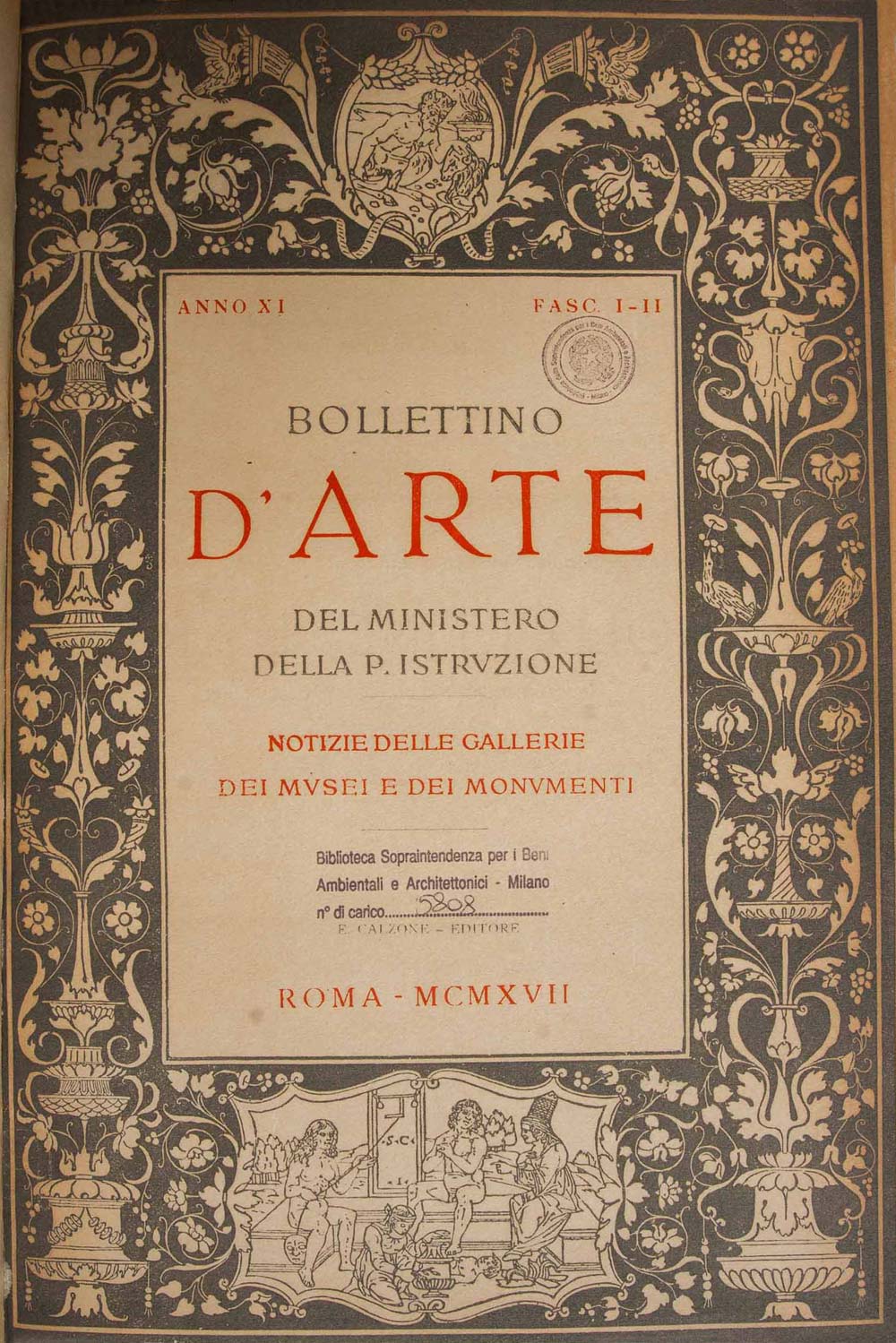

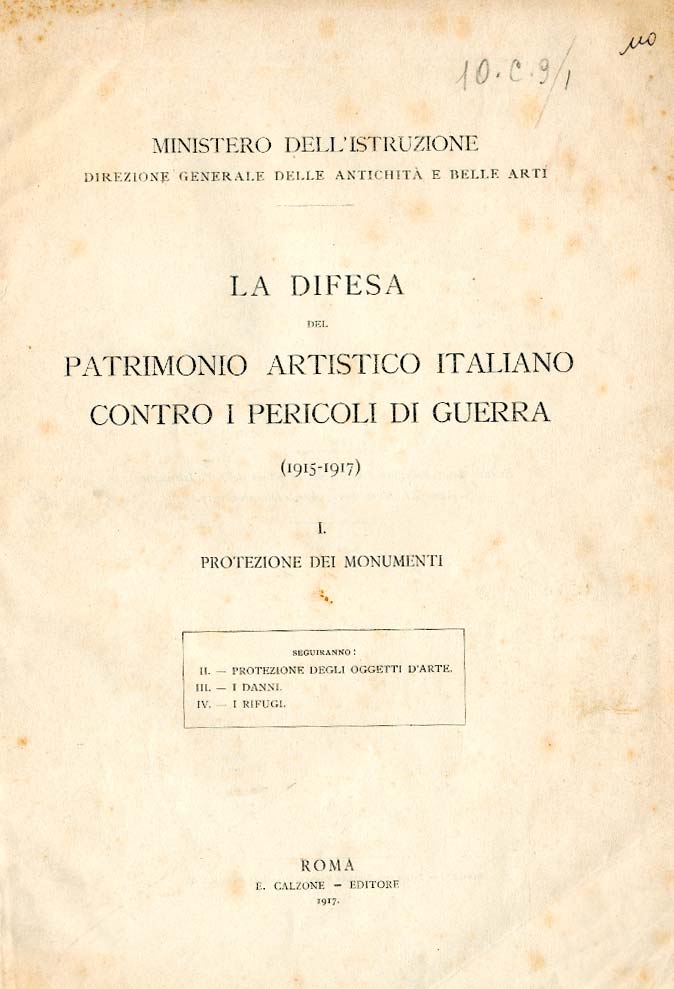

Ricci began his career in Bologna, where he was assistant librarian from 1882 to 1892, after which, in 1893, at the age of thirty-five, he was able to start his own career among museums: he first worked at the Pinacoteca di Parma (today’s National Gallery), of which he was also director, taking care of the new layouts, then from 1894 to 1898 he directed the Galleria Estense in Modena, while in 1897 he moved to the Soprintendenza di Ravenna, and again, between 1898 and 1903 he was director of the Pinacoteca di Brera before moving to Florence to lead the city’s museums (in particular, he worked to renovate the Uffizi and increase its photographic archives). His work enabled him to become, in 1906, director general of the Ministry of Education, which at the time was in charge of what we now call “cultural heritage.” Many were the results he achieved with his work at the ministry: A new general catalog of state property; the start, in 1907, of the journal Bollettino d’Arte, which is still published today; the hiring of staff exclusively by competition; and above all Law 364 of 1909, which for the first time in the history of Italy guaranteed an arrangement, within the ministry, of Italian cultural heritage (a law which, moreover, by also establishing rules on the trade in cultural property, greatly limited a scourge of the time, namely the illicit export of Italian goods). His tenure at the ministry ended in 1919: he resigned due to disagreements with the Nitti government and moved to the newly founded Institute of Archaeology and Art History, founded in 1918 and of which he became president in 1919 itself.

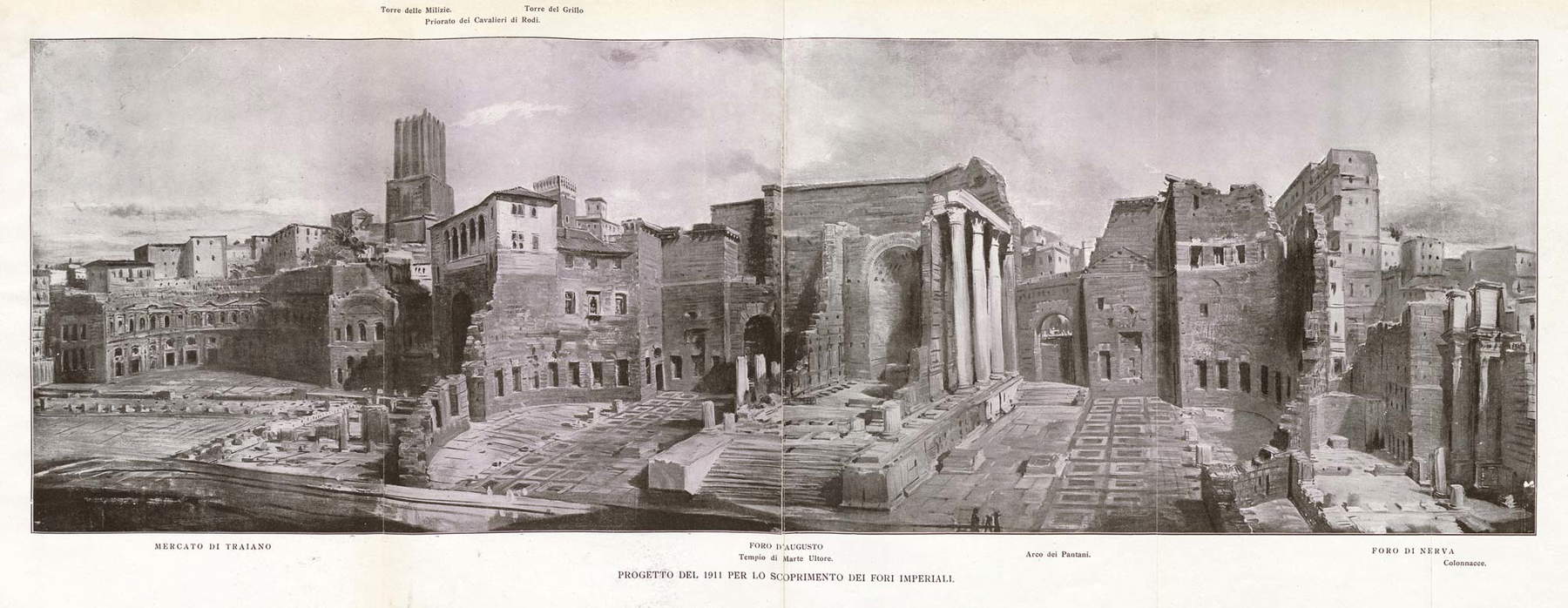

As a member of parliament, he spent himself mainly on the care and preservation of heritage (for example, it was he who managed the recovery of the ships of Nemi), and he played an important role in the arrangement that, in the 1930s, was given to the Imperial Forums (even today the largo in front of the Colosseum is named after him): however, it was precisely this last undertaking of his that weighed on his memory: “his restoration of the Fora, hailed at the time,” explains scholar Clotilde Bertoni in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani entry dedicated to him, “was later criticized profusely, particularly for its lack of attention to the urban context, failure to explore the ruins, and sloppy handling of the finds (he remained known primarily for his archaeological exploits, the scholar had no real expertise as an archaeologist).”

The Fund held at BiASA is not the only book collection dedicated to Corrado Ricci: there is another one at the Classense Library in Ravenna, which holds catalogs, books, journals, pamphlets, and an archive of correspondence now on display in three rooms of the Ravenna institution. BiASA’s Ricci Fund became part of the institute in 1934, after the scholar’s death: it was by his testamentary will that his bequest was divided between the Ravenna and Rome libraries. “The books and papers on the subject of Romagna and Emilia,” he wrote in his will, “go to Ravenna to the Classense. The latter may cede the duplicates to the Library of the R. Istituto di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte in Rome. Of the remaining books and pamphlets the said Institute will retain those that it lacks. Extracts from journals should not be put among these, for it is enough that it has them in any way. Everything, in short, the rest that constitutes the principal sum goes to Ravenna.”

Scrolling through the list of publications in the Ricci Fund, it is possible to get an idea of thecultural orientation of the archaeologist and art historian from Ravenna, an orientation that is indeed decidedly precise: “of Ricci,” wrote Maria Grazia Malatesta Pasqualitti, “the collection shows, like a reflection in a mirror, the biographical and cultural profile.” In addition to art books, auction catalogs, books dedicated to Dante Alighieri towards whom, a symptom of his age, he nurtured almost a veneration (Ricci also owned a monumental edition of the Divine Comedy illustrated by Amos Nattini), his library was rich in volumes dedicated toancient Rome, through which it is possible to read above all, Pasqualitti explains, “the sense of Romanity that for so many years had driven Ricci, a not improvised archaeologist, to the restoration of the Imperial Forums, to the study of the topography of the Trajan Markets and the Forum of Caesar, to the reconstruction of the Temple of Venus Genetrix, to the grandiose work of excavation that brought to light in his years the vestiges of the major temples of ancient Rome.” Ricci of the rest is also remembered for the recovery of Trajan’s Market, a project he conceived and which came to fruition between 1926 and 1934, when the modifications that had been made to the complex over the centuries were eliminated and the ancient Roman structure brought back to light.

Among the most important works that, according to scholar Amedeo Benedetti, best testify to Corrado Ricci’s archaeological interests are the book Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux mystères de Mythra by Franz Cumont, published in 1899 in Brussels, and then again by the same author the Études Syriennes of 1917, or the Studi e ricerche archeologiche nella Anatolia Meridionale by Roberto Paribeni and Pietro Romanelli, and again the book Monumenti antichi published by care of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, the volume Sculptures antiques en Libye by Rodolfo Micacchi, and Aristide Calderini’s Roman Aquileja: volumes that figured among the most up-to-date and innovative studies of their time. Ricci’s collection also included prints and drawings, including an album with original drawings by Ferdinando Bibiena, who was among the leading architects active in Italy between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A valuable fund, then, for understanding the choices of a figure who, although controversial in several respects, was among the most eminent in the field of conservation in the early 20th century.

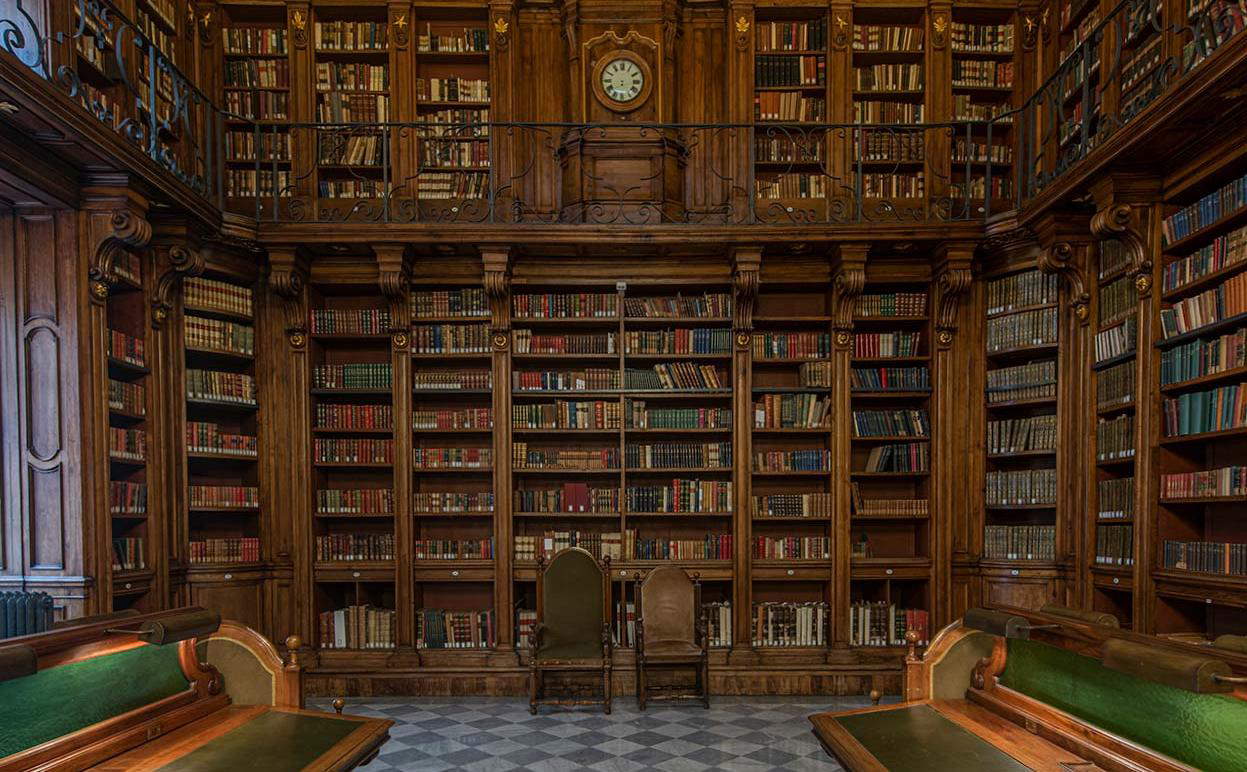

The Library of Archaeology and Art History in Rome

The origins of the Library of Archaeology and Art History (BiASA) date back to 1922, the year in which the Institute of Archaeology and Art History was founded, due to the initiative of Corrado Ricci. On that occasion, in fact, the Library of the Directorate of Antiquities and Fine Arts, which between 1915 and 1916 had been supplemented, at Ricci’s own behest, with funds from private collections, was transferred to the headquarters of Palazzo Venezia. The constituent nucleus of the library included a total of about 30,000 volumes, and from 1922 it was then gradually increased by donations and bequests, including that of Corrado Ricci himself, as well as by targeted purchases. In 1989, given the sheer volume of new acquisitions, a detached section was also opened at the Roman College Crossing. Meanwhile, the Library was beginning to develop its own autonomy from the Institute: thus, in 1967, BiASA broke away from the Institute of Archaeology and Art History to join the ranks of state libraries. A departure that was definitively sanctioned in 1995 with a name change: from “Library of the National Institute of Archaeology and Art History” to “Library of Archaeology and Art History.”

Today, BiASA is the most important Italian library specializing in archaeology and art history, and is recognized in Italy and abroad as a fundamental institute for study and research in archaeology, art history and contemporary art, architecture, decorative arts, collecting and restoration. The documentary holdings currently consist of about 370,000 volumes, 3,900 periodical titles, more than 20,000 units of graphic materials, manuscripts and archival collections, incunabula, sixteenth and seventeenth century books, theater posters and CD-ROMs.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.