The origins of the Romance languages pass through Sardinia: and here, on the island, at the University Library of Sassari, is preserved one of the oldest “’monuments’ of the Romance languages” (as the scholar Giovanni Strinna has defined it), namely the Condaghe di San Pietro di Silki, a precious manuscript codex (indeed: “the most valuable piece in the University Library of Sassari,” according to scholar Francesco Artizzu), consisting of 125 parchment papers (there were originally 143, however), containing four distinct registers of the monastery from which it takes its name, which in ancient times was home to a Benedictine women’s community. The Sardinian term “condaghe” derives from the Greek Kontaktion, Latinized into Condacium, and used to refer to the staff around which the volumen was wrapped: there is evidence of the introduction of this term in Sardinia at the time of Byzantine rule (534-698 AD), and it was used to refer to a regesto of an administrative nature, that is, a set of different acts (such as purchases and sales, donations, bequests, permutations, decisions of disputes), which concerned monasteries in particular. For German linguist Max Leopold Wagner (Munich, 1880 - Washington, D.C., 1962), the Condaghes are “a collection of deeds of gift, compre, bequests of provenance, which form the patrimonial holdings of the monasteries.”

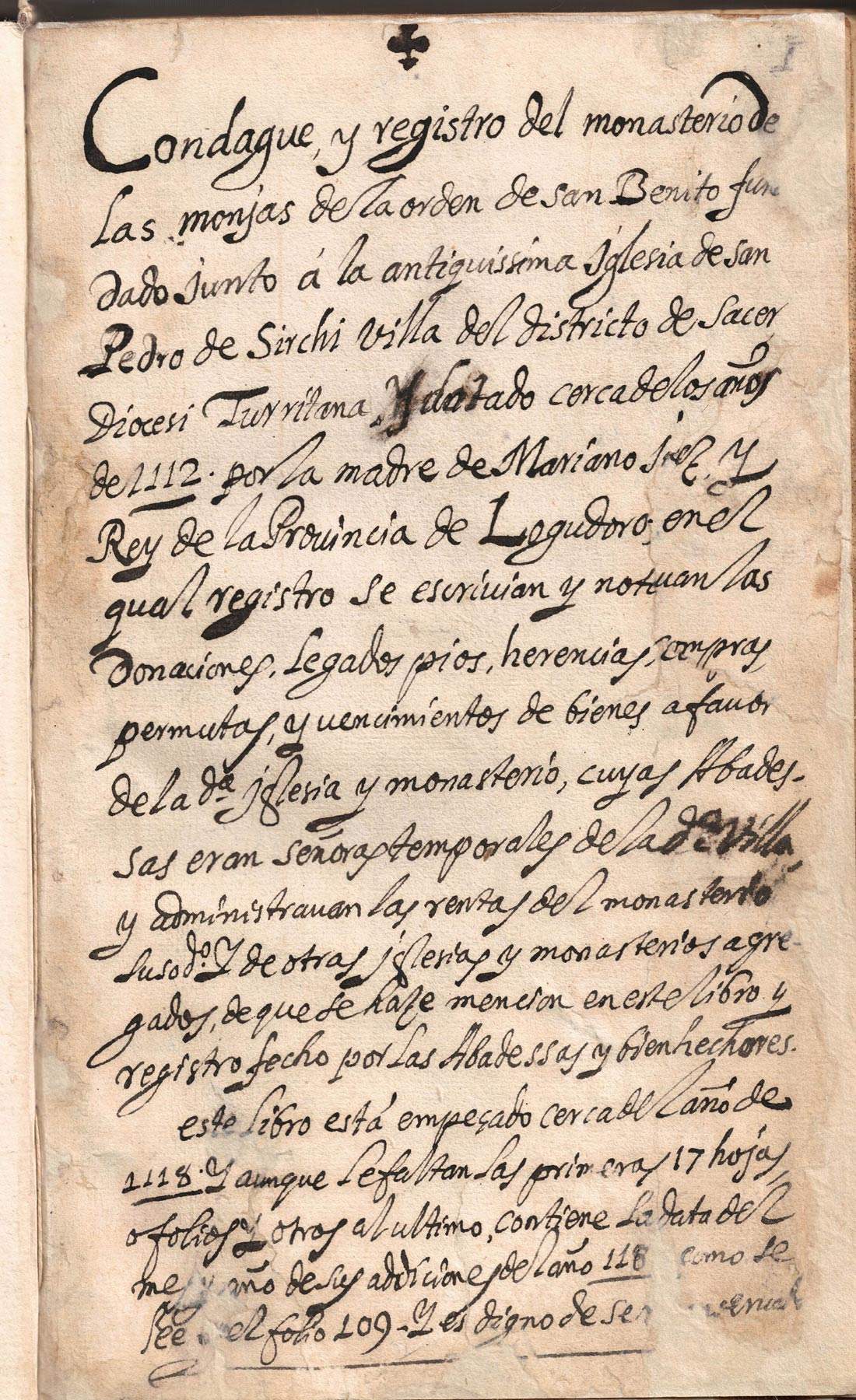

All the Condaghes that have come down to us belong to monastic entities that were located in the areas of the giudicato of Torres and the giudicato of Arborea (two sovereign states whose territories extended over northwestern Sardinia: the former lasted from the 9th century to the mid-13th century, when it came under the control of Genoa, and the latter from about the year 1000 until 1420, when the kingdom was sold to the Aragonese and Sardinia for the first time became united, albeit under foreign rule). They are all written in Sardinian Logudorese: the only exception is that of St. Michael of Salvennor, which has come down to us in a Castilian translation from the late 16th century. The Condaghe di San Pietro di Silki is the most important both in terms of the quantity of acts it contains and the time span it covers, since its documents range from the mid-12th century to the mid of the 13th, although the originals of some of the transcribed acts date from the late 11th century (there is, however, a guard sheet, the one located between the cover and the text to protect the latter, which contains a note in Castilian and dates from the 18th century: it is a decidedly important note because it represents the first known attempt at a bibliographical description of the codex). Not all the acts, however, refer to the monastery of St. Peter of Silki: some documents concern the houses of St. Quirico of Sauren, St. Mary of Codrongianos, and St. Julia of Kitarone. This is why di speaks more properly of a “composite” codex, that is, a collection of Condaghes referring to several places, even though they are uniform registers, set up in all probability in a single scriptorium.

Condaghe

Condaghe Condaghe

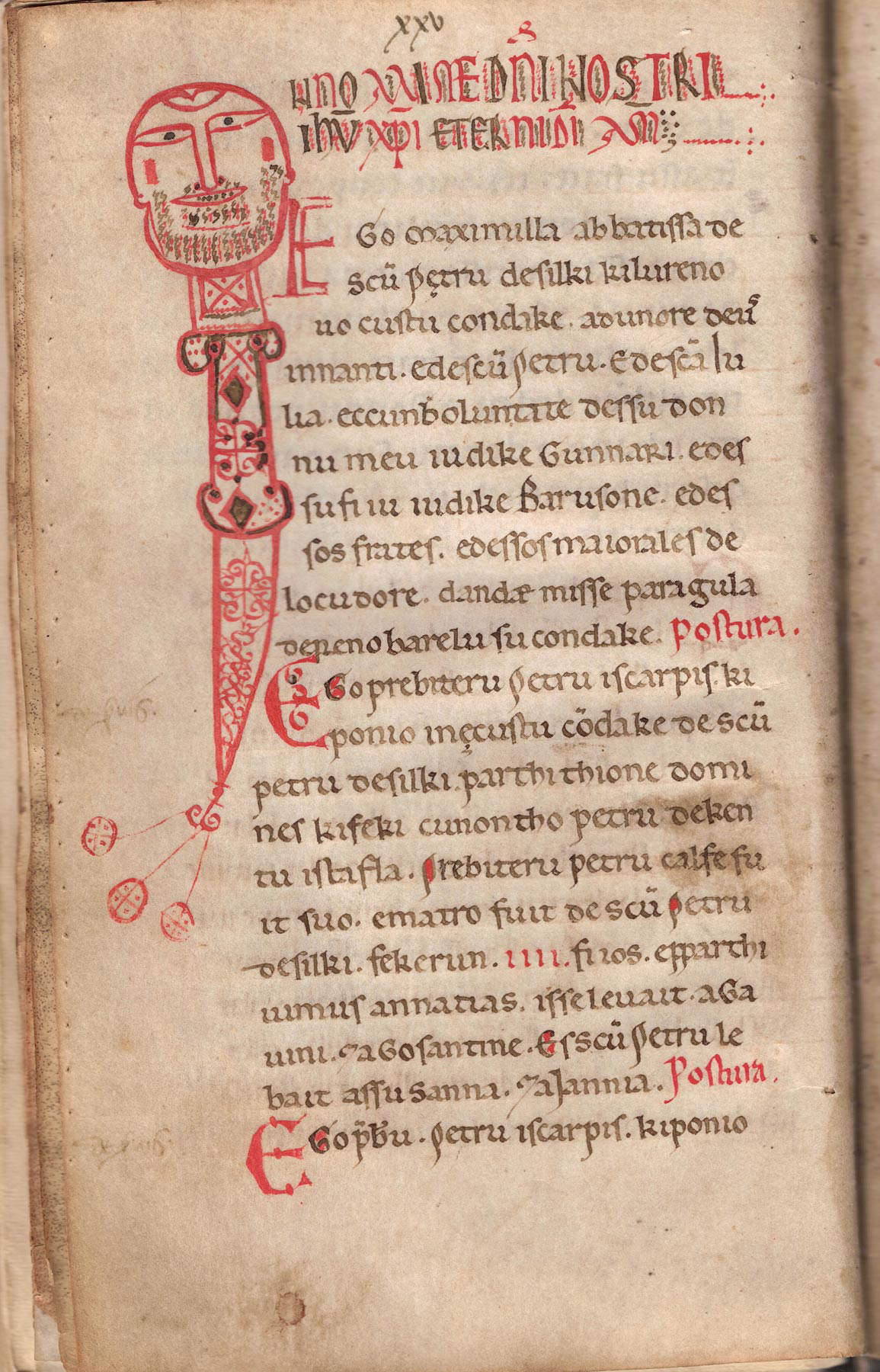

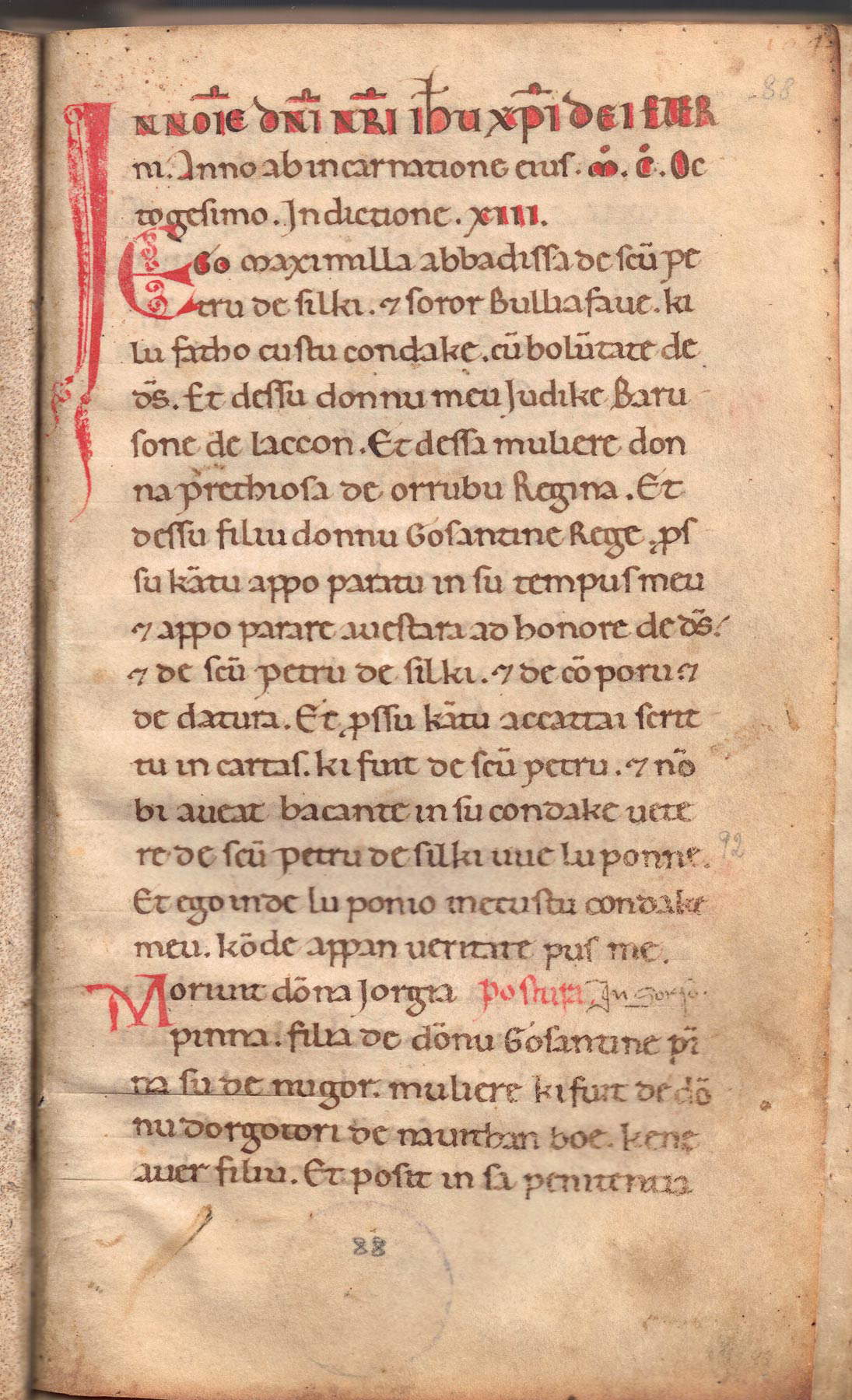

CondagheThe Condaghe of San Pietro di Silki is then particular because it conceals a partly female history. First of all, it must be premised that the recording of the acts was done on individual parchments which were then, with the permission of the judge of Torres, copied onto special quaternions (files of four sheets). And it is thanks to the rationalization work promoted by Abbess Massimilla, who lived during the 12th century, that much of the documentation of St. Peter in Silki has come down to us. Massimilla, having obtained the authorization to create a new Condaghe (so we read on folio 88r), had in fact transcribed the acts until then preserved in the Condaghe of San Pietro in Silki (which therefore must have been in a very poor state of preservation) to one of her nuns, known by the name of Bullia Fava (or Bulliafave): “it would be,” Strinna explains, “one of the rare attestations of female writings in the area not only Sardinian.” The Condaghe opens precisely with Maximilla’s declaration that she intends to have the codex renewed: “Ego Maximilla, abatissa de scu. Petru de Silki ki lu renouo custu condake, ad unore deus innanti, e de scu. Petru e de sca. Julia, e ccun boluntate dessu donnu meu iudike Gunnari, e dessu fiiu iudike Barusone, e dessos frates, e dessos maiorales de Locudore, dandem’isse paragula de renobarelu su condake.”

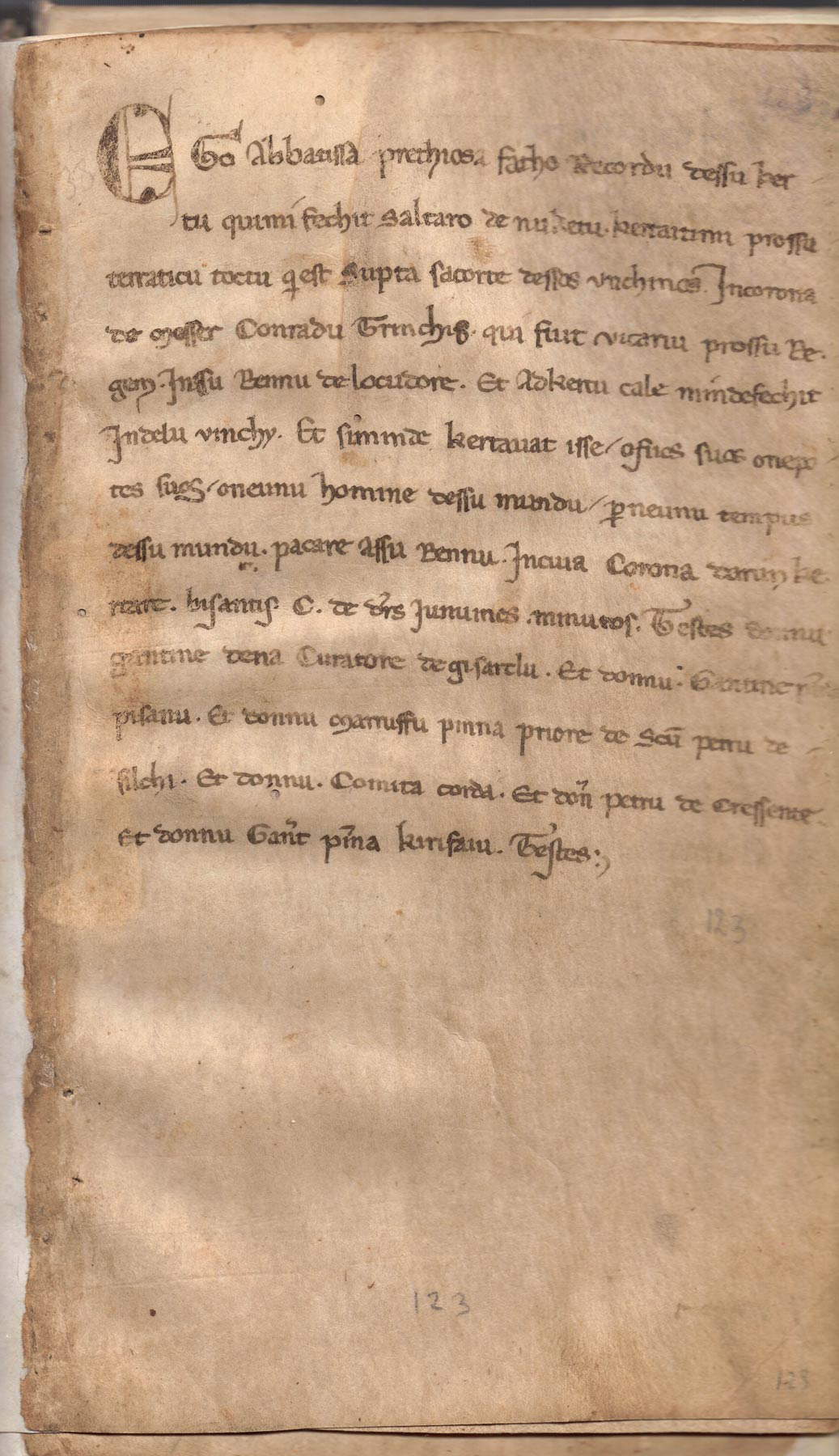

And it was precisely from the papers of the Condaghe that it was possible to derive the names of the abbesses who ruled the monastery sees from the 11th to the 13th century: Theodora I, Massimilla, Jena, Speciosa, Maria, Benvenuta, Theodora II, Preziosa, Agnese, and Susanna. “These are,” explained Francesco Artizzu, "women of strong commitment and character, who recognized how their office derived per issa gratia de Deum, directed not only to witness Christ with sas sorres manacas but also to defend the rights of the monastery and to defend and increase the patrimony of the landed property entrusted to the monastery."

The cards did not reproduce the originals in their entirety, but still preserved the authenticity of the recorded deed. It is difficult to find the date: however, the deeds are often marked with the day of the religious or civil holiday on which they had occurred. The structure was almost always the same: after an intitulatio, that is, a brief initial protocol, which sometimes might be preceded by an invocatio to Christ, the essential elements of the legal action were listed, namely, the names of the parties, the type of document, the subject matter of the document, the characteristics of the subject matter itself (e.g., the extent, location, and boundaries of a piece of land, the price, and so on), and finally the deed closed with a list of the witnesses who had taken part. The majority of the records that make up the Condaghe of St. Peter of Silki are donations in favor of the institution (150 documents), but there are also numerous judicial disputes (97 documents), mainly concerning property, while immediately after that come deeds of purchase (87 documents). This is followed by exchanges (40 documents), partitions of servants (35), land confines (11), and authorizations for transcription of deeds (4). The Condaghe is then completed by an annulment of an exchange, an assignment of collateral, a grant of property, a genealogy of serfs, a manumission of serfs, and a restitution of pledged property. These are highly relevant documents for understanding the structure and functioning of society at the time of the giudicato of Torres: in particular, the role of the monasteries, which constituted communities with their own precise legal identity, but also important economic (they were organized as businesses) and political, as well as religious, centers, is of considerable importance.

The four registers of which the Condaghe is composed were written by different hands (about thirty have been recognized: the texts were in fact renewed at different times), by amanuenses who had been trained by observing Tuscan calligraphy: the handwriting is in fact a late Tuscan Carolinian of good quality. The original cover has not been preserved: the one that currently covers the Condaghe was adopted in 1969 to replace a modern-era cover.

The Condaghe of St. Peter of Silki remained until the nineteenth century in the monastery’s library, although it was no longer the same monastery that had seen the birth of the registers: in 1467, in fact, the archbishop of Sassari granted it to the Observant Friars Minor, who decided to erect a new building on the site of the older one (the Benedictine nuns had already abandoned it in the early thirteenth century). In the nineteenth century, the Condaghe was an object already known to local scholars and historians, and it is therefore curious to know that in 1867, at the time of the demanations that followed the suppressions of the monastic orders established after the Unification of Italy and that also affected the book heritage of St. Peter of Silki, which was therefore forfeited by the demanio, the manuscript was found to be missing. The friars, probably caring for the fate of the manuscript, in fact took it out of the monastery to secure it. Although it cannot be ruled out that the Condaghe had left the monastic library at the initiative of someone who wanted to sell it privately.

It reemerged only in 1897, when the director of the Library of the Royal University (as today’s University Library of Sassari was then called), Giuliano Bonazzi, unearthed the manuscript from a young watchmaker, and bought it for the price of 140 lire, corresponding to about 625 euros in 2022. According to Bonazzi, after the death of the religious man who kept the manuscript, the Condaghe ended up in a country house, hidden in a chest, which somehow (we do not know how) reached the watchmaker: the latter thought of selling it to a tobacconist who would make paper out of it to wrap cigars. The merchant, however, was fascinated by the strange handwriting that covered the sheets for him, and so, advised probably by someone who had guessed its antiquity, he went to Bonazzi to have it examined: this, then, is how the Condaghe came to us. Bonazzi himself edited the first edition of the text, published in 1900 and reprinted in 1979 and 1997. It was necessary to wait until 2013 to see the new edition of the manuscript, edited by Alessandro Soddu and Giovanni Strinna, revised and accompanied by a critical apparatus, with glossary and index of names and places. Today the Condaghe, completely restored, is preserved among the rare and valuable books in the Antique Collection of the University Library of Sassari.

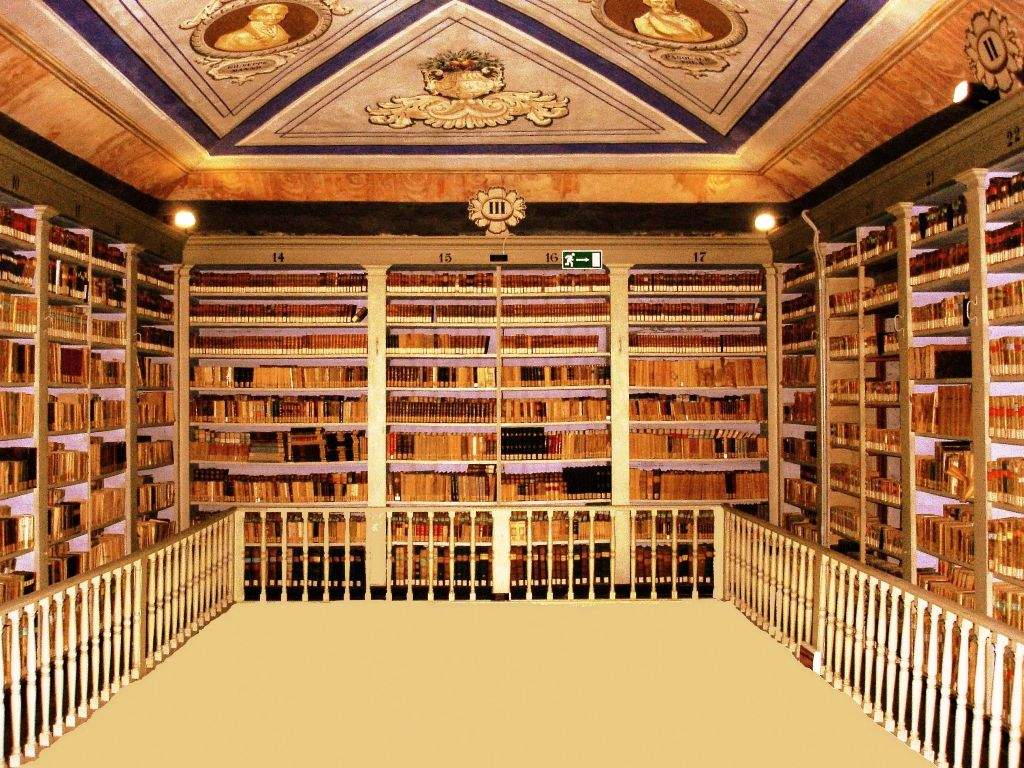

The University Library of Sassari has a centuries-old history: in fact, it was born in 1558, with the bequest that the jurist Alessio Fontana, an official of the imperial chancery of Charles V, destined for the foundation of a Jesuit College. Fontana’s book collection was then acquired in 1632 by the University of Sassari: from then on, the fate of the founding nucleus of the library became linked to that of the Sardinian university. The library’s holdings continued to increase over the following centuries, especially following the legislative provisions of 1855 and 1866 that suppressed religious corporations. The event allowed the library to take possession of numerous book heritages from the monasteries of Sassari. Particularly important was the direction of Giuliano Bonazzi, between 1896 and 1899: the increase in the collections experienced a significant boost (it was he who acquired the Condaghe di San Pietro di Silki, the institute’s most important manuscript), and the library itself was equipped with new facilities, such as reading rooms and catalogs by authors and titles.

Currently, the institute has about 300,000 volumes, including 74 incunabula, 3,500 cinquecentines, about 4,600 works from the 17th century and 3,300 from the 18th century. Among the most important pieces in the Sassari University Library are, in addition to the Condaghe di San Pietro di Silki, a nautical chart on parchment from the 16th century (it illustrates the Mediterranean basin and is decorated with sea monsters and symbols of cities), the Statutes of Castel Genovese, a membranous Bible, manuscripts by Domenico Alberto Azuni, Grazia Deledda and Salvatore Farina, a hundred maps of Sardinia printed from the 15th to the 19th century (about half of the latter were acquired in the 1970s under the direction of Maria Carla Sotgiu Cavagnis). Also worth mentioning are prints by important Sardinian painters such as Giuseppe Biasi, Mario Delitala and Stanis Dessy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.