The compelling story of Albrecht Dürer's Madonna of the Patronage, the marvelous panel from Bagnacavallo

In the choir of the Monastery of the Capuchin nuns of Bagnacavallo a small Madonna and Child of the highest quality was jealously guarded until 1969: the nuns kept it wrapped in a blanket and protected in a dowry case; those who wished to admire it could do so only through a grille. The fame of the work of art grew enormously, so much so that it became quite complicated for the nuns to keep up with those who declared their desire to observe that small but immense masterpiece, when the skillful hand of Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528) was recognized in the latter, thanks to the knowledgeable Monsignor Antonio Savioli and the confirmation of Roberto Longhi.

The history of this small panel known as the Madonna del Patrocinio, already so named by the Faenza artist Angelo Marabini (Faenza, 1818 - 1892) who made a mediocre engraving of it in the first half of the 19th century (although the attribution is debated, it could be the work of his father Vincenzo), thus testifying to the now recognized role of devotion and protection ( “patronage,” precisely), turns out to be compelling and at the same time exciting, considering that fifty years have passed since the painting is no longer kept in Bagnacavallo, but thanks to the long-awaited event that marked its return even to the same location where it was carefully guarded for decades by the Capuchin nuns, the people of Bagnacavallo were able to enthusiastically welcome back their Madonna and Child. Until February 2, 2020, the Dürerian work is on display at the Museo Civico delle Cappuccine, which is none other than the aforementioned ancient monastery, to be admired by as many people as they wish.

But how did a Dürer masterpiece come to be in a modest monastery in the Ravenna area and why has it now been kept for fifty years, albeit in total approval, at the Magnani Rocca Foundation in Mamiano di Traversetolo? The return of the Madonna of the Patronage to Bagnacavallo made it possible to take stock of the situation regarding up-to-date knowledge and critical contributions on the painting.

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Madonna del Pat rocinio or Madonna of Bagnacavallo (c. 1495-97; oil on panel, 47.8 x 36.5 cm; Mamiano di Traversetolo, Magnani-Rocca Foundation, inv. 581) |

|

| The Convent of the Capuchin nuns in Bagnacavallo, now the site of the Capuchin Civic Museum |

|

| Vincenzo Marabini, Beata Vergine del Padrocinio (1832?; burin, 120 x 78 mm) |

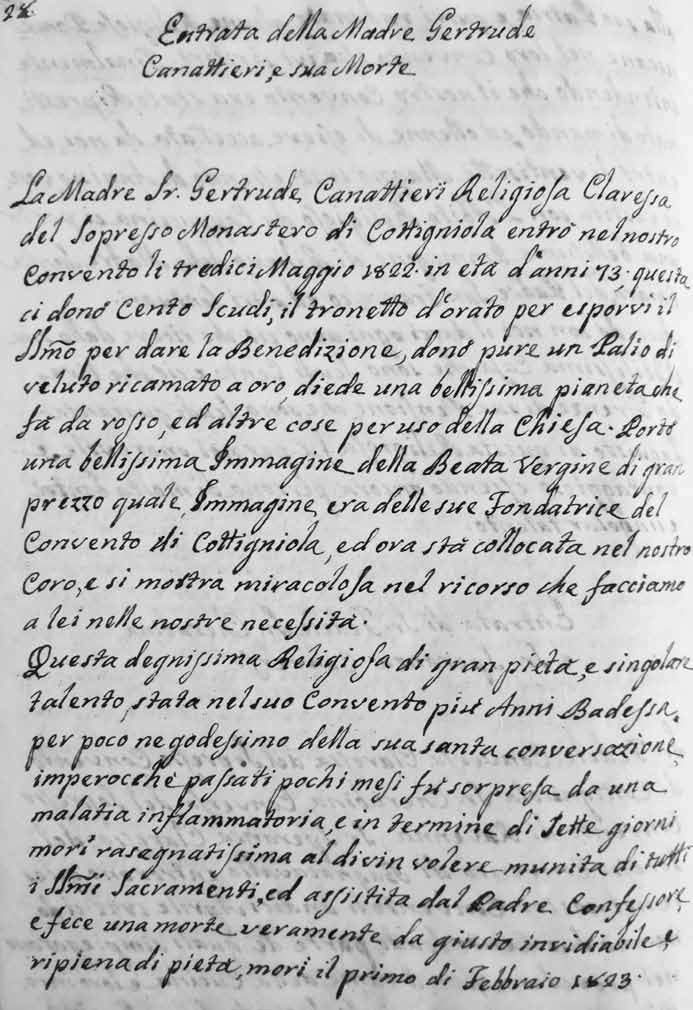

The Capuchin nuns remembered that they had always guarded and venerated that Beata Vergine del Patrocinio, but in reality it was an asset that had arrived there through one of their sisters, from one cloistered convent to another cloistered convent: it was Don Antonio Savioli who, in the course of his research to discover the true provenance of the table, read in the book Campione delle monache di Bagnacavallo: “La Madre Sr. Gertrude Canattieri Religious Claressa of the suppressed Monastery of Cotigniola entered our Convent there May 13, 1822 at the age of 73 years [...] She brought a beautiful image of the Blessed Virgin of great price which Image was of her Founders of the Convent of Cottigniola, and now it is placed in our Choir, and it shows itself miraculous in the recourse we make to her in our needs.” The convent mentioned in the annotation was the cloistered convent of the nuns of Santa Chiara in Cotignola, established in 1659, whose foundresses were Sister Dorotea Felice Certani and Sister Giovanna Maria Scapuccini. In the Lives of the Venerable Blessed Saints and Servants of God of the Diocese of Faenza collected by Romoaldo Maria Magnani in 1742, however, it is found that Sister Dorothea was “most devout of the B.Virgin, before an image of whom, believed to be by Guido Reni, she was many hours in prayer: And she had a vision of it one day through this one, to which she made warm supplications. ”A manuscript Life of Sister Dorothy was also found in the Convent of St. Clare in Ravenna compiled by a Poor Clare who, intrigued by the biography of the nun without, however, having had the opportunity to know her personally, gathered news from the older sisters who had known her. Here we read that “she had as a gift from her Lord Father a beautiful image of this Virgin” before which “the good Mother was kneeling many hours a day” for the “graces she desired both for her, as well as for her Daughters and their relatives”; but above all we have news that the sacred image “brought her from Ravenna to our Monastery.” Documents attest that Sister Dorotea, born Isabella, entered the cloister in 1621 with a balance of scudi 500 made by her father and, according to the regulations for becoming a nun in the Monastery of St. Clare, had been obliged to bring with her a painting depicting a sacred image, probably precisely Our Lady of the Patronage. Her father, Giovan Filippo Certani, traded silk in Bologna, but he was also an artistic-literary patron: he founded theAccademia dei Selvaggi, in which artists such as Guido Reni or the Carracci participated, so owning paintings was not complicated for him; perhaps he had purchased the Madonna del Patrocinio on the Bolognese art market or perhaps in Venice through entrepreneurs who traded for luxury manufactures. Or, since many members of Sister Dorothea’s family were monks or nuns, the painting may have passed between them. In any case, it is known that when Dürer arrived in Venice in 1506, the artist communicated in a letter addressed to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer in Nuremberg that he had sold five of his six small panels of which all trace has been lost.

As mentioned earlier, the Dürerian masterpiece arrived in the Monastery of the Capuchins in Bagnacavallo thanks to Sister Gertrude Canattieri of the Cotignola monastery, and it remained there until 1969, ten years after Monsignor Antonio Savioli discovered that it was a painting by the Nuremberg master. Some priests who frequented the convent had learned of the existence of the small panel, without associating it with its author, even before 1959, and rumors spread, reaching the ears of Savioli, who, intrigued, began to ask the nuns for a good photograph of the work in 1958: the year before, in fact, the nuns had distributed the first photographic images of it to the faithful. However, the live meeting between Savioli and the work took place in September 1959, but only through a double grate. “I expressed a desire to study it, and was sent a dull postcard, old and faded photo,” he declared. The painting had also been targeted by Antonio Corbara, honorary government inspector for mobile works of art in Romagna, who wrote to the Capuchins in 1961, “Do they know the value the work has? Do they have data on its provenance? It is extraordinary that such a piece is there, it is a case of unprecedented rarity,” adding that “it would be advisable that, for the time being, they do not authorize anyone to reproduce or publish it.” In addition, Corbara asked to be allowed to see the work up close in order to draw up the ministerial card to later report to Superintendent Cesare Gnudi. The work ’s card and the publication of the first study on the painting, however, fell to Savioli, in the January 1961 issue of the Bollettino Diocesano di Faenza: here the attribution to Albrecht Dürer appears for the first time, attributable to the German master’s second Italian period , that is, between 1505 and 1507, during which he stayed in Venice. “The work, which is reported for the first time through the present card, will certainly be the object of study by critics and historians,” it reads; and after describing the painting, it states, “At first I sought, without result, the painter among the Lombards of the Leonardo diaspora. But a pale photograph was enough for Prof. Longhi to discover the hand of the great Dürer, a name pronounced by him and as if blown under the impulse of a disturbing intuition.” Indeed, in July 1961 Roberto Longhi’s unpublished text dedicated to Dürer ’s Madonnain Bagnacavallo came out in Paragone Arte, where the Nuremberg master’s authorship was confirmed.

This incredible discovery soon caused quite a few problems, however: first of all, special permission was needed to go and admire the painting, as one had to enter a cloistered place, but, having overcome this, it was realized that the Capuchin nuns, with their limited means, were the custodians of a work of inestimable economic value, and in addition the latter did not know how to respond to the numerous requests that came to them from all over Italy and abroad. There was an imminent need to make the work accessible to the public, and if at first a possible restoration was thought of absolutely within the monastery so as not to make the painting leave that location, ministerial officials convinced Savioli that it was necessary to think about a safe transfer to a suitably equipped laboratory: in Gnudi’s opinion, in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna.

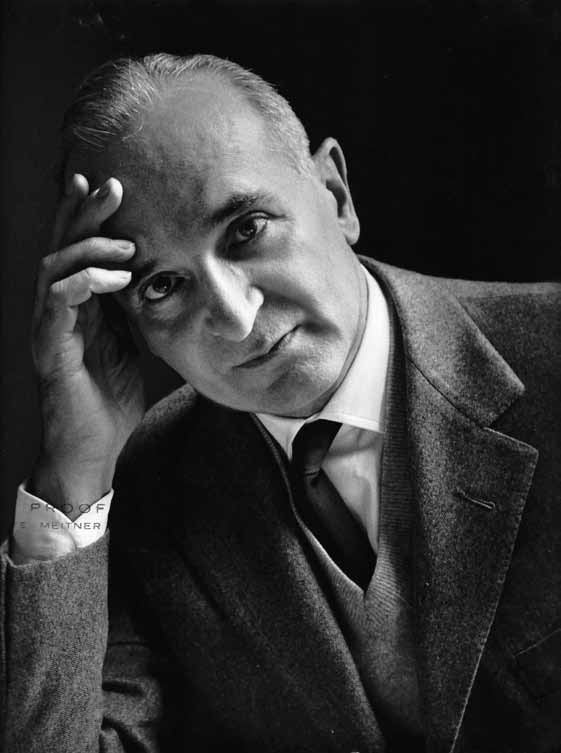

Faced with all these hypotheses, the nuns also presented the idea of selling the work, aware that the Bagnacavallo monastery was in a state of decay and that, rather than face renovation, they were willing to move to another location; with the sale of the work, their project would be possible. Gnudi was totally opposed to the sale to a third party mainly as a matter of cultural heritage protection and appealed to the law that required the minister’s authorization in order to sell a protected property belonging to a church institution. Optimal condition was to find a buyer agreeable to the General Directorate for Antiquities and Fine Arts who could give guarantees of preservation and public enjoyment of the work: a condition that arose in 1966, when Luigi Magnani (Reggio Emilia, 1906 - Mamiano di Traversetolo, 1984), a musicologist and collector from Reggio Emilia, visited the Madonna del Patrocinio for the first time in an interested way. Often the same ministerial officials in charge of the protection of the artistic heritage fully supported Magnani’s desire to “save and recover to Italy masterpieces threatened by obscure destinies,” partly because of the fact that the latter provided guarantees of subsequent devolution to the state or public enjoyment of the works. All agreeing to sell the work to Magnani, the contract was signed in December 1968, even overcoming the unexpected ending of the nuns’ surprising refusal to give the painting to him. These, to conclude, in addition to the amount of money, demanded a reproduction of theDürer masterpiece as faithful as possible to the original.

|

| The recording of Sister Gertrude Canattieri’s entry into the convent. |

|

| The 1957 image (photo by Giuseppe Zauli) |

|

| Luigi Magnani |

|

| The image of Our Lady of the Patronage before the 1970 restoration. |

Instead, the people of Bagnacavallo reacted worried about the loss of the painting: the municipal administration did not want the painting to be transferred to another town, commenting that there was a Museo Civico in Bagnacavallo that could have housed it, but in fact the museum existed only on paper, since it was not a real museum, but simply a room set up in the local library, unsuitable for housing a work by Dürer. The panel left town in secrecy in February 1969 to reach Rome, where it underwent a delicate restoration at theIstituto Centrale del Restauro to restore it to its original state.

Of restorations the work had undergone substantially two, “one,” Longhi wrote in his essay, “perhaps intended to remedy the effects of an old burn, includes the entire lock of hair falling to the right of the Virgin’s face and for the remarkable skill of execution shows that it was conducted by a hand ’philologically’ trained and therefore, I would say, not before the century of the ’’Enlightenment’’; the other, rather than a true restoration, is an addition that, by providing to disguise certain parts of the Child, shows that it was induced by post-Tridentine moralistic scruples.” So, in Rome, in addition to the consolidation and cleaning of the surface, they intervened by removing thepictorial integration on the lock of the Madonna’shair made in all likelihood between the 18th and 19th centuries following a candle burn and the small loincloth added in the late 16th century to the Child for moral reasons.

It is a work of extraordinary value and beauty, and Antonio Savioli was already aware of it when he first described it in the Diocesan Bulletin of Faenza: "Iconography of Mater Christi. The holy Child holds a small strawberry branch in his right hand, gazes into his Mother’s eyes, and clings to her left hand as if to secure his own balance. He is lying sur nappy-white, he is all naked except for the loincloth that is a late addition, perhaps. The Virgin looks softly and almost contemplates the divine Son. She wears the red robe. The blue mantle folded over the head leaves the white cap sheathing the opulent braid visible. The backdrop, to the right of the viewer, by a nineteenth-century engraver was interpreted as a window, and the monochrome flourish as the terminal decoration of a parapet. If, on the other hand, it were, as it seems, a door, one would have to think of a closing gate, beyond which, in any case, one sees a wall of bricks bound by white lime. On the left, however, the bottom is occupied by a wooden frame or cornice pillar. The main light diffuses from a source on the left with an incidence of 45° to the plane of the painting."

Savioli associates it with the iconography of Mater Christi, but in reality, as Raffaella Zama commented, we are dealing with a Compassio Mariae, that is, a reflection and devotion to the pain that Mary experienced in experiencing the passion and death of her Son. The Child’s small left hand clinging to the Mother’s hand hints at the latter’s tragic thoughts prefiguring her son’s hand being pierced by the nail of the Passion, but other elements hint at this: the dark color of the Virgin’s mantle suggests mourning; her gaze is tender and sweet toward the Child but at the same time it is sad and melancholy; and again, the Child interrupts his play with the sprig of red strawberries, which allude to his Passion, to search in vain with his gaze for his mother’s eyes. In a single image, Dürer has managed to condense the tenderness between the Virgin and Child and the Passion of Christ, leading our minds to the revelations of St. Bridget of Sweden, according to whom, whenever Mary looked at her son and saw his hands and feet, she was seized with intense grief, because her foreboding thoughts led her to the sufferings and death on the cross.

From a technical point of view, the Madonna of the Patronage absorbs Nordic elements, from the Nuremberg master’s origins, and Italian elements into a single work: an aspect that has been debated regarding the identification of the period of the work’s creation. Longhi, in his essay published in Paragone Arte, confirmed the painting’s association with Dürer’s second Italian journey between 1505 and 1507, arguing that the master had reached his maturity and thus was more conscious inassimilating Italian formalisms and recovering the art of his Nordic origins. In contrast, other critics argued that the work dated to his first Italian sojourn, in the mid-1590s, asserting an earlier encounter with the Italian Renaissance. However, many of the examples of Italian artists that Longhi cites in his essay hark back to the 1590s: “The layout dl divine group is, at the first, of Bellinian and Antonelloesque cut [...] A calm, ’pyramidal’ calibration, with almost no heteroclite strokes; a very sweet oval in the Mother; a vivacity, but regulated and almost of calm gymnastic exercise in the body of the Child that approximates, more than to other Italians, to the Vicentine Montagna: an artist whom Dürer may have seen on his way down from the Trento Alp before setting out for Venice”; and after a few lines he comments that “the Virgin’s cap, which has just been said to be Montagna-like, descends to cover almost the entire forehead in the guise of a northern ’béguine’ monk’s blindfold as Dürer had insistently used in engravings prior to the second journey. The domed shoulders of the great and noble Italian bodies become narrow and missing; the shining copper-stranded hair spreads out in an asymmetry that is incomprehensible to us, with no longer any relation to Italian syntax.” However, he concludes by stating that “this deliberate contradiction even in linguistic mixture is of such subtle engagement that Dürer can only have experienced it in the years of his second Italian journey between 1505 and 1507, between Venice and Bologna.”

However, comparing the Madonna del Patrocinio with other works of the late 15th century, one finds elements in common, as Diego Galizzi argues. First of all, the work’s pyramidal composition suggests the motif of the seated Madonna looking out from a low parapet typical of theMantegna and Bellini circles, such as Giovanni Bellini ’s Madonna of the Red Cherubs (Venice, c. 1433 - 1516). The backward flap of the dark mantle on the Virgin’s head, with the rust-colored lining, harks back to many Madonnas of the 1490s by Cima da Conegliano (Conegliano, 1459/60 - 1517/18), such as the Madonna and Child in the Petit Palais in Paris. And again, Bartolomeo Montagna (Orzinuovi, 1449/50 - Vicenza, 1523) used to depict the central fold dividing the Virgin’s white bonnet in half , a motif of Nordic origin that in fact Dürer often used in his Madonnas, including the Washington Haller Madonna of about 1498.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Madonna of the Red Cherubs (1485; oil on panel, 77 x 60 cm; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

|

| Cima da Conegliano, Madonna and Child (1495-97; oil on panel, 71 x 55 cm; Paris, Petit Palais) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Haller Madonna (c. 1498; oil on panel, 50 x 40 cm; Washington, National Gallery of Art) |

|

| Martin Schongauer, Madonna of the Parrot (c. 1470-75; burin, 155.8×107 mm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Sheet with Various Studies (c. 1495; black and gray ink pen on paper, 370 x 255 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, inv. 1049E) |

Moreover, Savioli had already noted the “northern syntax of the figure of the Virgin,” and indeed the face of the Virgin in the Madonna del Patrocinio reflects a late Gothic model from southern Germany: the oval contour of the face, the arched eyebrows, the downward-sloping eyelids, the tapering nose, the small mouth; these are features found in the works of Martin Schongauer (Colmar, c. 1448 - Breisach am Rhein, 1491), one of them being the Madonna and Child with Parrot made by burin between 1470 and 1475.

In the figure of the Child , on the other hand, a Verrocchio model had been recognized: a drawing by Dürer preserved in the Louvre and dated 1495 testifies to his knowledge with respect to a model attributable to Lorenzo di Credi (Florence, 1459/60 - 1537), one of Verrocchio ’s most notable pupils (Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488). And a sheet dating from about 1495 kept in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe at the Uffizi, on which the Nuremberg master had practiced some studies of Italian Renaissance art, reveals precisely in the lower left corner of the sheet a small seated Baby Jesus taken from a prototype by Verrocchio or Lorenzo di Credi. The small Baby Jesus turns out to be very similar to the Child depicted in the Madonna of the Patronage, although the artist modified it to fit the particular iconography of the painting: the Child’s left hand joins that of his mother and his other hand clasps a sprig of red strawberries.

It is a painting that reveals much deeper iconographic and sacred meanings than the mere depiction of a Virgin and Child, and it is therefore evident, in light of all this, the deep connection that this work had with a prayerful environment such as that of the Monastery of the Capuchin Poor Clares of Bagnacavallo, where now, fifty years later, it has returned to be admired by all in its full splendor.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.