One of the most interesting and comprehensive collections of prints by Rembrandt (Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn; Leiden, 1606 - Amsterdam, 1669) to be found at the State Library of Cremona is housed in a public institution. There are 108 in all and they have been in Cremona since 1824, the year in which what was then the Cremona Governmental Library, of which the state library is a direct descendant, received by bequest the collection of Rembrandt prints from Abbot Luigi Bellò (Codogno, 1750 - Cremona, 1824), born Giuseppe Antonio Belò, who was a refined scholar, Latinist, and art collector. Bellò left his engravings to the library on the condition that they be kept in excellent condition. Bellò, who had studied at the Jesuit college in Cremona, had a vast literary culture and was also a good writer, and he also became politically involved in the administration of his city, especially in the last thirty years of his life. Highly esteemed by the people of Cremona, he was also responsible for the expansion of the library collection, which Bellò considered insufficient for the needs of the city, and he therefore worked to have his library holdings replenished (although he did so at the expense of the ancient collection, part of which was sold: this was, however, a practice not blameworthy for the mentality of the time, as the sale of the ancient core was considered necessary to equip Cremonese students with modern, up-to-date instruments).

The collection of Rembrandt engravings that Bellò had collected and that is now part of the collections of the Cremona State Library “is of a remarkable consistency,” wrote Luisa Cogliati Arano, “such as to allow a precise idea of Rembrandt’s graphic art.” Rembrandt’s engraving activity was conspicuous and of great significance: his ability “to overcome color,” Cogliati Arano further states, “in favor of light finds in the black and white of graphic art the most timely expression and reaches unparalleled heights with him. Whether it is a portrait, a landscape or a sacred or profane scenic representation always the work reveals the interpretative wisdom of light [...]. With the graphic medium Rembrandt expresses himself exactly as in painting.” But it is not only the intense use of light that makes Rembrandt’s etchings masterpieces: the Dutch artist knew how to use the graphic medium to render images with a dramatic charge, psychological acuity and depth of feeling equal to those of his works on canvas. What’s more, prints were a means of spreading the fruits of his art throughout Europe. There are about three hundred prints that the artist made throughout his career, roughly from 1626 to 1665, and his career as an engraver was conducted in parallel with his career as a painter, and above all, it had an autonomous character: in fact, Rembrandt hardly used the medium of print to reproduce paintings. On the contrary: Rembrandt was one of the first artists to abandon the concept of print as a means of reproduction.

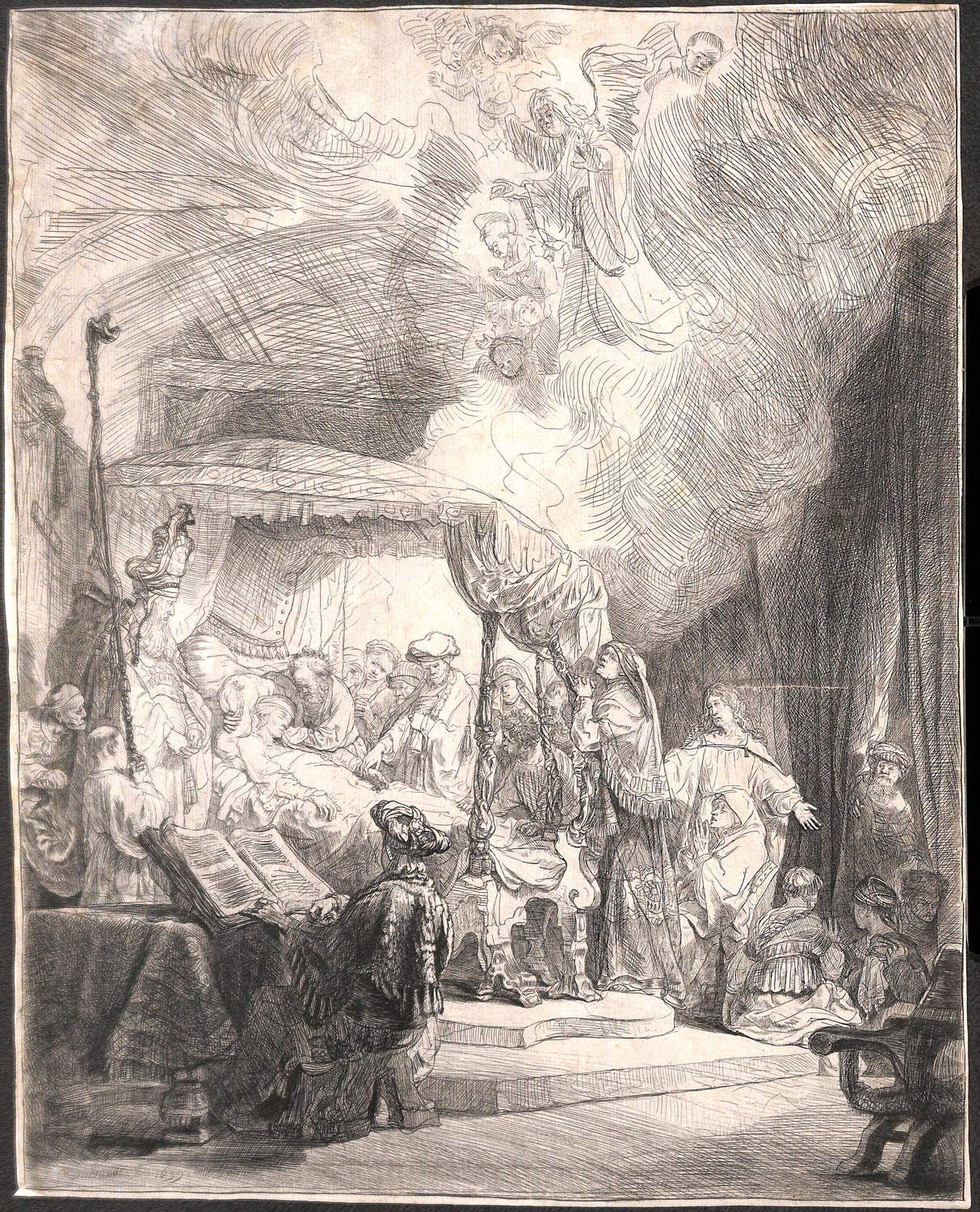

Rembrandt,

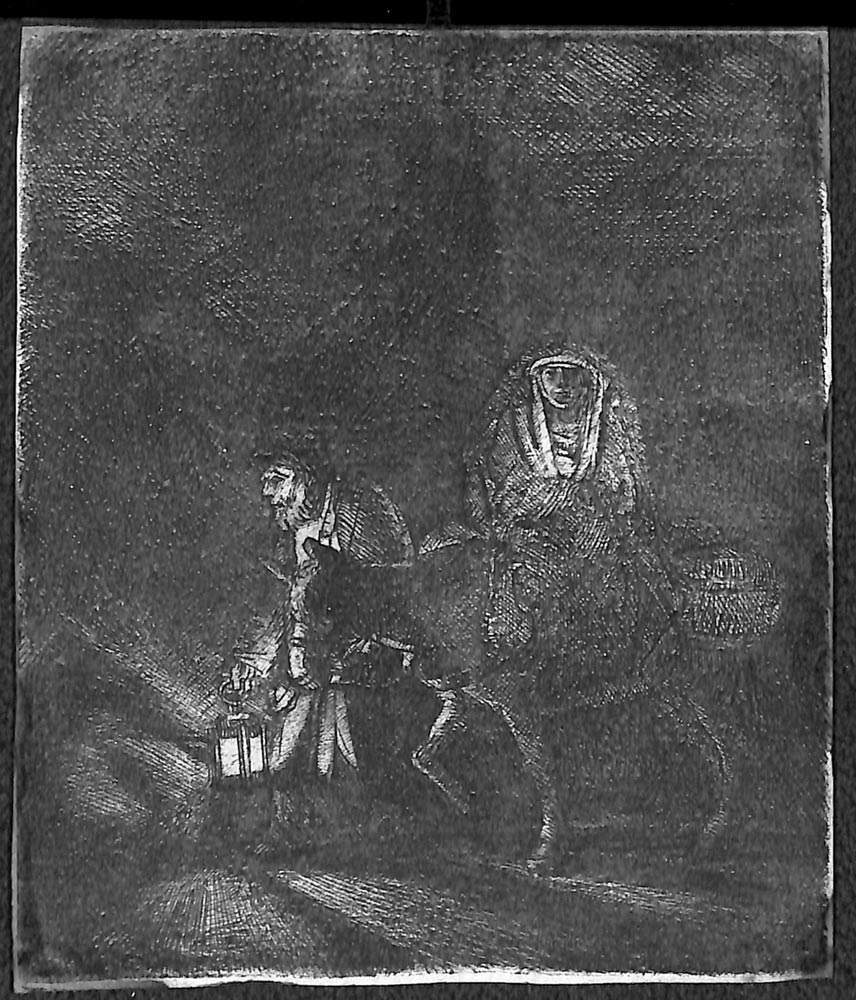

Rembrandt,

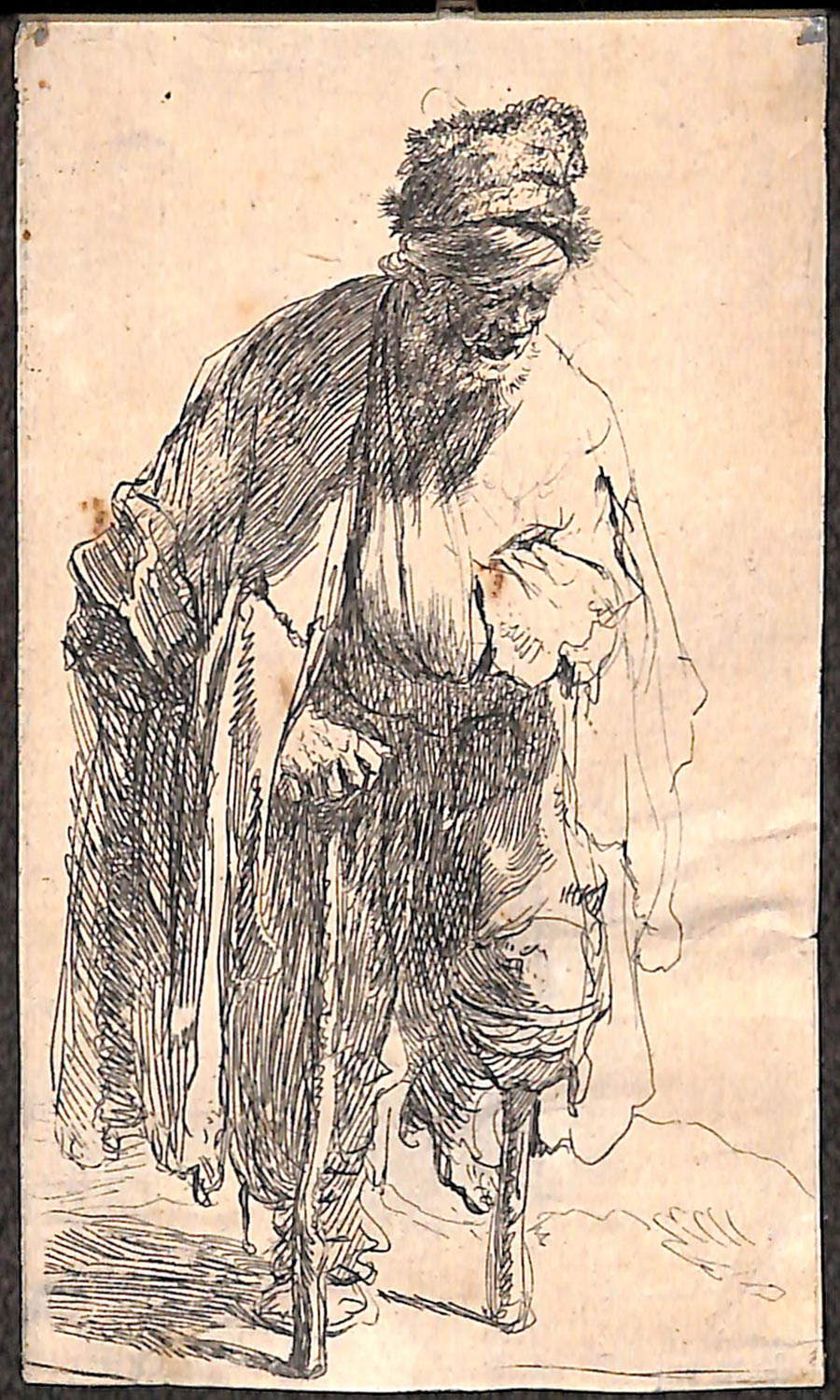

With prints from the State Library of Cremona, it is possible to take a journey through Rembrandt’s entire career, since the prints from the Lombard institute start from Rembrandt’s beginnings as an engraver to his most extreme stages. The earliest prints seem to look at what was being realized in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in Italy and France: in particular, Rembrandt looked to two masters of graphic art such as Antonio Tempesta and Jacques Callot, drawing from the latter very useful insights into an expressive evening of light even with the poverty of the graphic medium of expression. In particular, the relationship with Callot is evident when Rembrandt chooses to refer to the Frenchman’s Beggars, a series published beginning in 1629. However, the flavor of the representation changes: if for Callot it was mainly a matter of investigating the subjects to return almost genre scenes, in Rembrandt the figure of the beggar becomes a means to study the relationships between light and shadow. They are thus, at the same time, exercises that a Rembrandt new to etching performs in order to become familiar with the medium, and pretexts for investigating the reality of the time: these trials will later lead the artist to the creation of the Portrait of the Mother, the first dated work in the Cremonese collection (it is dated 1631), which is notable for its remarkable expressive force and for the life that the artist manages to instill in the mother even with the simplicity of etching.

Rembrandt’s interest in the humble transcends what he had learned from studying Callot: the Dutch artist, Ottolini further writes, “sees the pitocchery in an epic and at the same time caducous dimension and participates with great humanity in the fate of his heroes.” The first genre subject, as well as among the most famous of Rembrandt’s graphic production, is the Rat Poison Seller, depicted trying to offer his product to poential buyers at the threshold of a door. A work that met with great success, given the high number of copies that were made of it. It is evident how in this sheet, dated 1632, we see a kind of evolution of the early studies of beggars, with a more pronounced attention to detail and psychological rendering. These are qualities that Rembrandt would refine not only in later genre scenes (such as the intense Beggars Receiving Alms at the Door of a House of 1648), but also with a view to the making of portraits, since in portraiture the rendering of feelings is fundamental. Rembrandt is famous for his painted self-portraits, but his prints also abound with depictions of his image: in the Cremona collection there is, for example, theSelf-portrait with his wife Saskia of 1636, in which the artist, in the foreground, depicts himself looking at the viewer with his consort just behind, or theSelf-portrait leaning against a parapet in which there is a reflection on the very famous Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione by Raphael Sanzio preserved in the Louvre. Then there are very evocative portraits such as that of the goldsmith Jan Lutma, a work of 1656 in which the effigy is depicted in an armchair while holding a statuette in his right hand: with a certain economy of means (note the hatching of the face), Rembrandt succeeds in this portrait in suggesting to the viewer the absorbed dignity of the personage. Remarkable then, again, is the attention to detail, of which Rembrandt in this engraving gives an example, for example, in the buttons on Jan Lutma’s jacket, or again in the objects on the table, in the decorations on the back of the armchair.

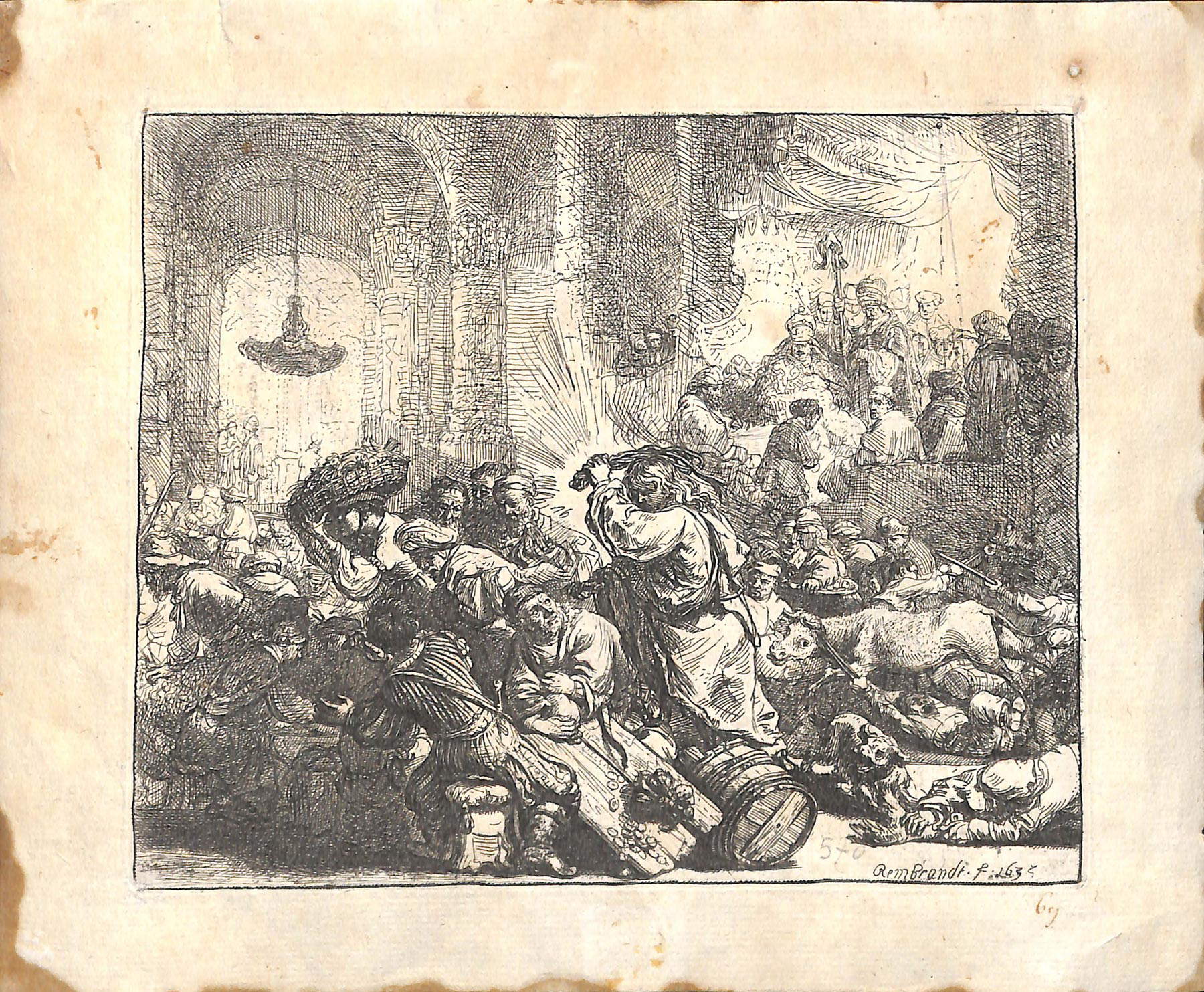

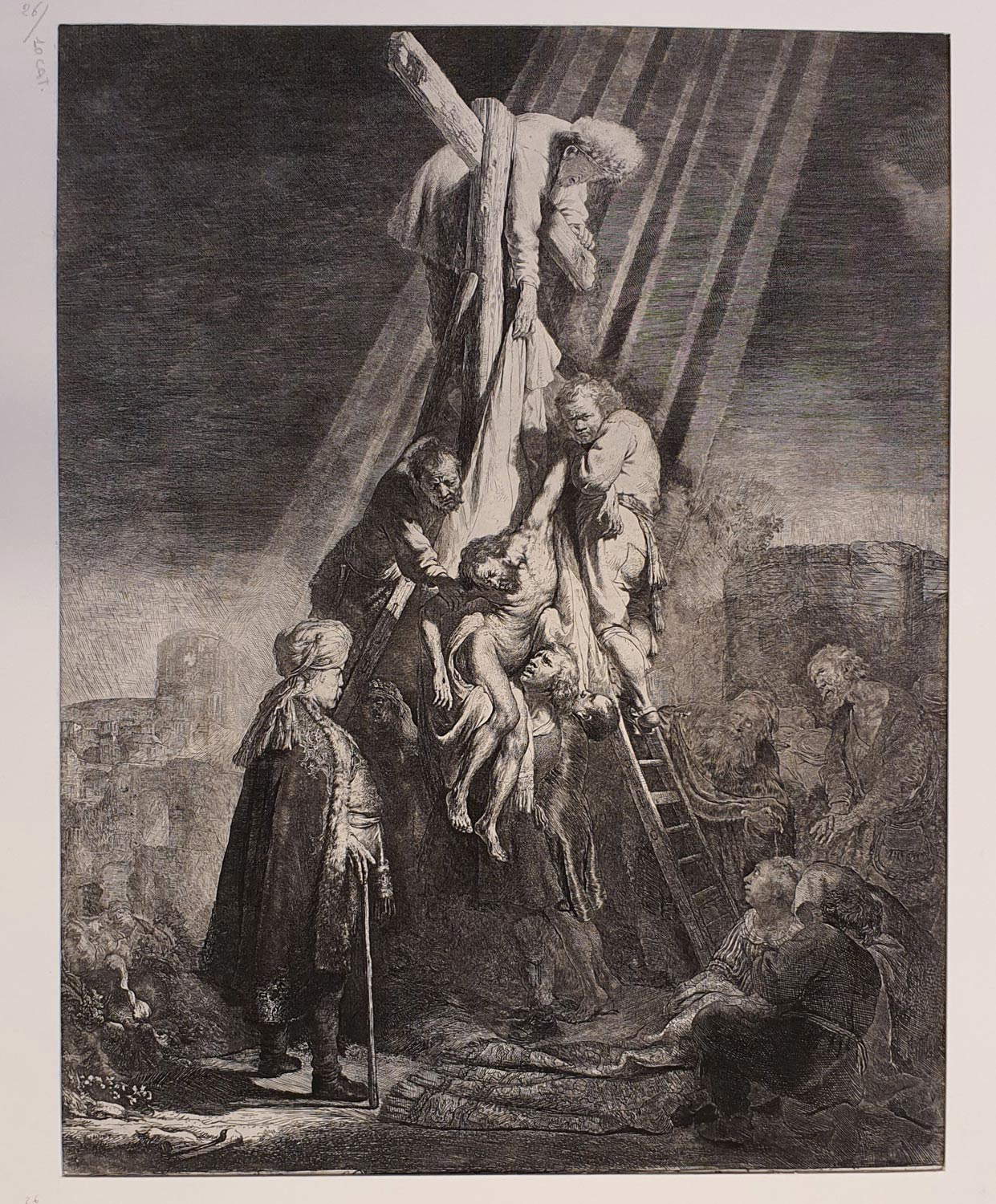

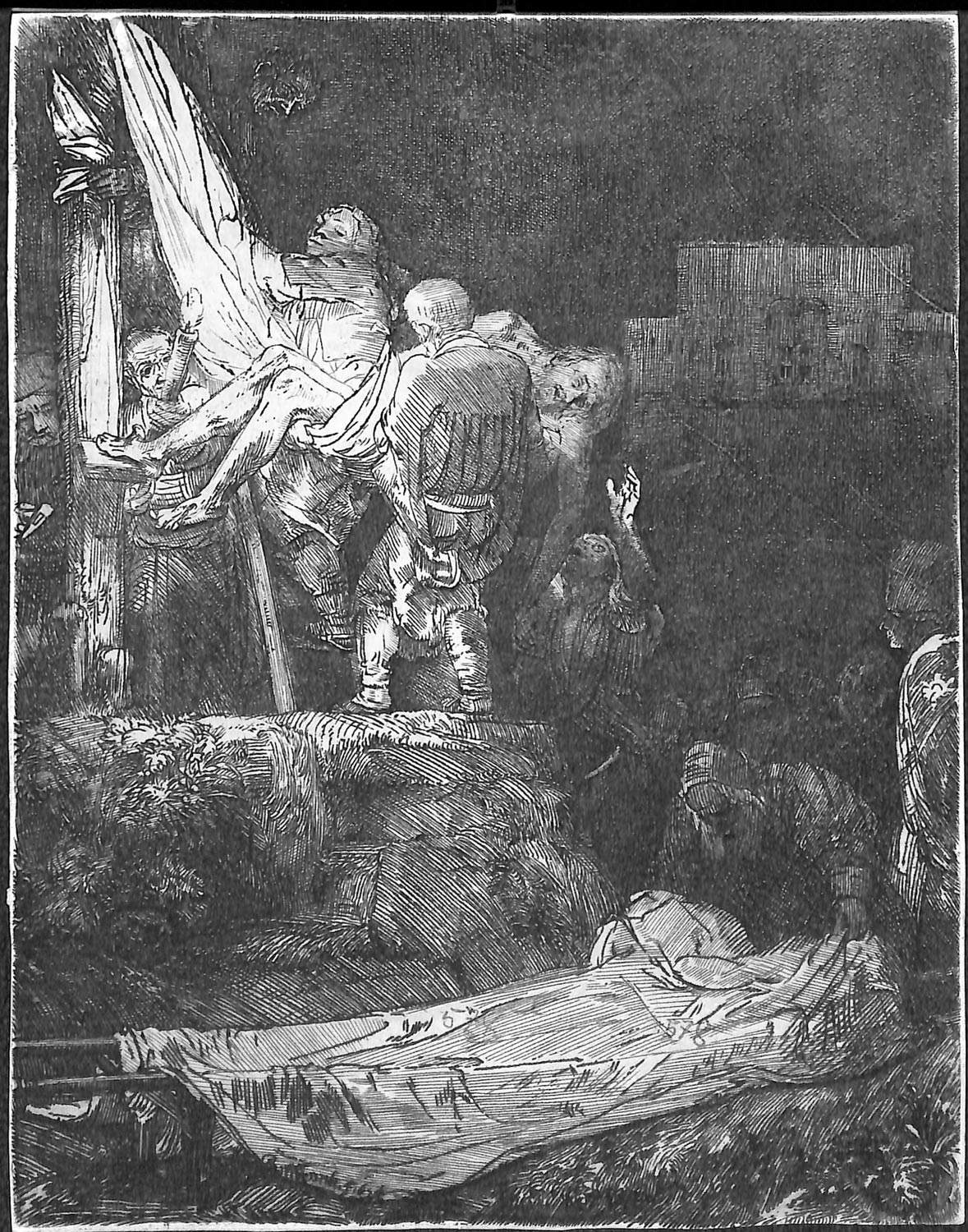

After all, Ottolini wrote, “it is only through a systematic and punctual analysis of the details that one can approach the complexity of Rembrandt’s world,” with an attention that can also make one understand how “even when he seems to conform to the Baroque taste of his patrons, in reality he hides, behind the apparent desire to emulate for acclaimed models, the ability to consistently pursue his stylistic research.” This can be seen, for example, in the 1635 Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple, which, despite its Baroque layout, “shows the agitation of the scene in the foreground almost blocked stiffened by the severe architectural structure of columns, which with great contrasting effect isolates the upper part of the Temple where a sacred rite is taking place and from where the priests corruptly observe the wrath of Christ.” The work is probably inspired by a painting by Jacopo Bassano kept at the National Gallery in London, while it looks to Rubens for an engraving with a much more solemn layout, the Deposition from the Cross of 1633, where the scene is charged with sincere drama (note the participation of the figures below) that is further highlighted by the divine light coming from above, which, in one of the most intense pieces of Rembrandtian graphics, dazzles the figure on top of the cross, who is holding back the cloth so that Christ’s body does not slide down. The print echoes, albeit with modifications, the canvas preserved at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, where the light, however, comes to invest the body of Jesus much more directly than in the engraving. Similar intense light effects are what we see in the later Deposition in the Light of a Torch, from 1654, where we notice a decidedly more vigorous stroke, a much more daring with the cross cut off and the main scene all shifted to the left, and with the detail of the flashlight that illuminates the base of the cross to cast light on the men intent on detaching the body of Jesus, which finds its geometric counterpart in the shroud on the ground, with Joseph of Arimathea caught preparing it. It is a work that not only reveals an extremely original construction, but also denotes a distinct narrative taste, with the light tending to highlight only a few details of the figures.

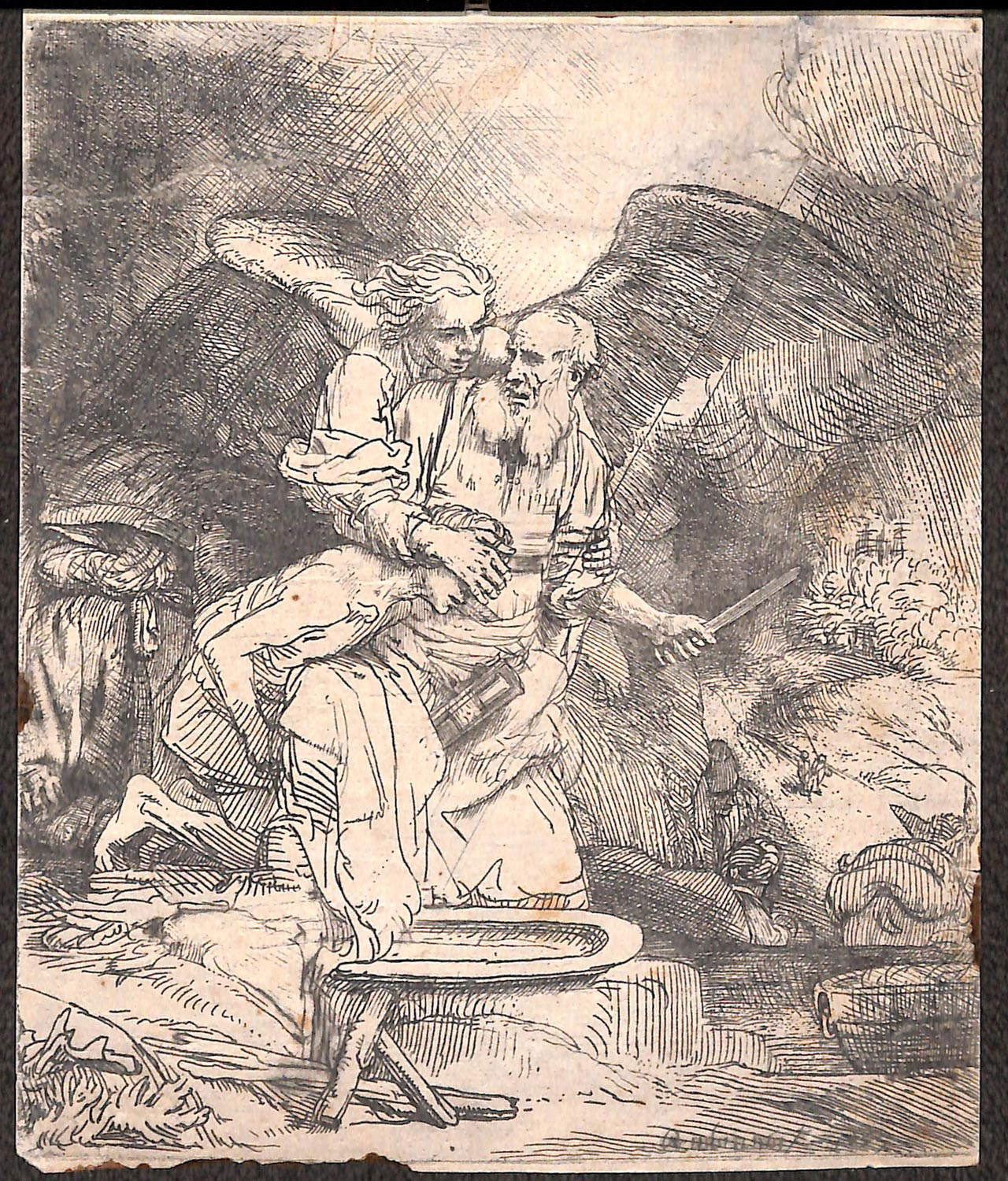

Among the many prints with a sacred subject, it is possible to mention first of all Christ before Pilate, which is notable for its monumentality, probably reminiscent of Titian’s Pesaro Altarpiece, and again for its highly dramatic accents, and then again the Death of the Virgin, which originates in works on the same subject by Martin Schongauer and Albrecht Dürer and which also cites Andrea Mantefna in the male figure with outstretched arms that can be seen immediately near the canopy. Rembrandt, in this etching, masterfully reconciles the human and divine elements with the skillful juxtaposition of the elaborate architecture of the bed and the figures arranged around the lifeless body of the Virgin, and the swirl of clouds above: a “free sky,” Cogliati Arano called it, “depicted with unusual light-illuminated hatching,” where “the angelic presences that will welcome the dying woman move. Rarely has a happier effect been achieved in a graphic work.” Again, pathos reaches one of its climaxes in the delicate Madonna with Child in the Clouds, a work where Rembrandt seems “to want to simultaneously affirm that motherhood in itself is sacred and worthy of veneration” (thus Ottolini), while among the peaks of luministic effects must be included the 1651 Escape to Egypt, one of Rembrandt’s best nocturnes, worked densely with interweaving cuts in different directions to achieve the desired darkness and the consequent light effect, with the Child shining by his own light and illuminating the Virgin and St. Joseph. By contrast, the Sacrifice of Abraham is an interesting essay in plastic sensibility, with the figures of Abraham, Isaac and the angel standing out sculpturally against the background, almost as if they were made of marble, in one of the most monumental pieces of Rembrandt’s graphic work, also charged with drama.

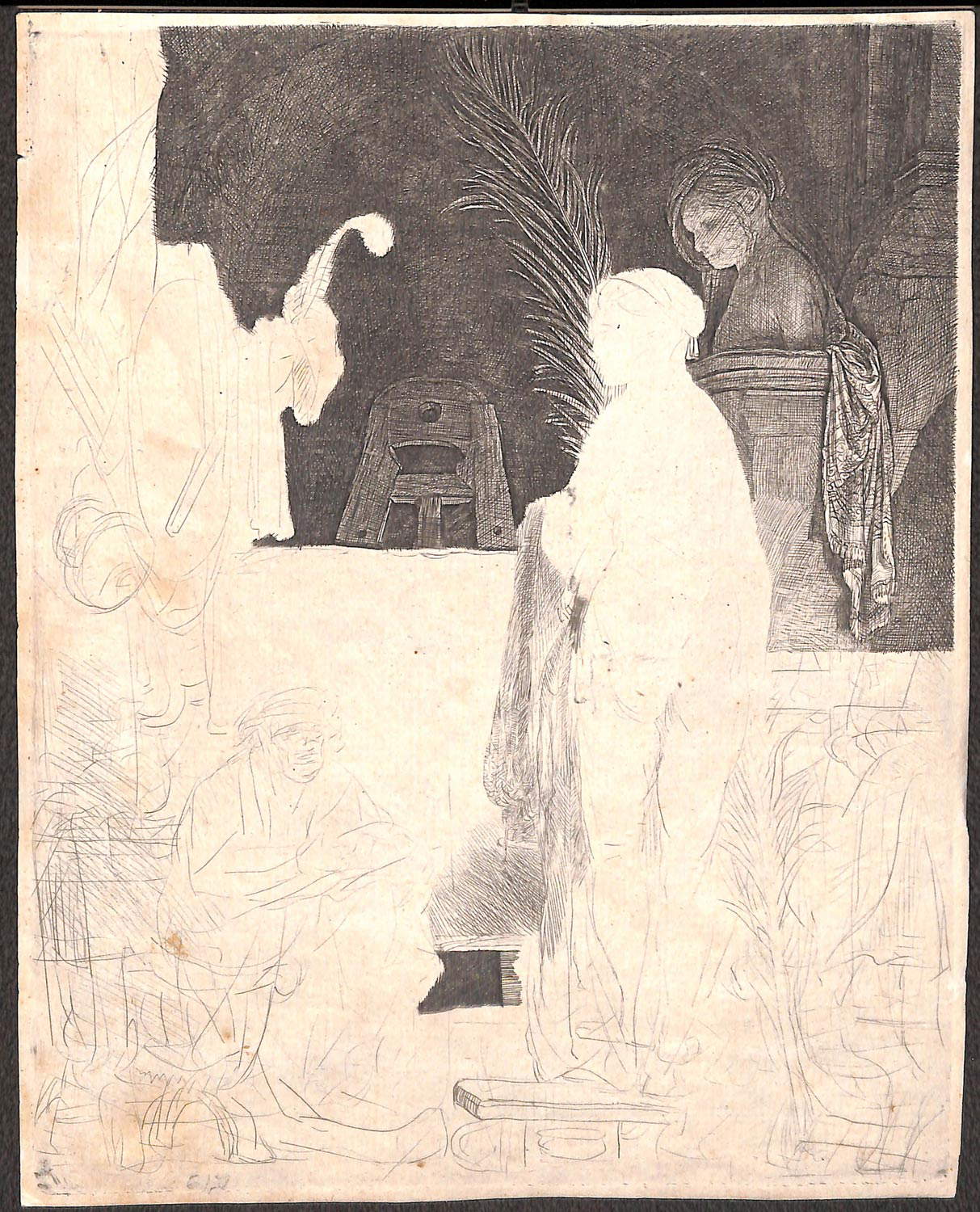

Finally, a very particular drawing, which is difficult to date, is of great interest: known as the Draughtsman with Model, it is of great significance because it is unfinished, so it is a fundamental testimony to understanding what Rembrandt’s execution technique was, from the initial sketch to completion. It is, moreover, a work that circulated while Rembrandt was still alive, thus proving to be a more unique than rare case in which an unfinished work, probably without the artist’s intention, achieved success and excellent feedback. Rembrandt therefore traced an initial drypoint sketch, which could, however, be modified since some afterthoughts are noted, and then moved on to a subsequent working of the plate with much denser interlacing and hatching in order to ensure plasticity and solidity to the figures, to work out the details and to create the effects of light, relief and depth: it has been speculated that the artist deliberately left this etching of his, perhaps to make it a suitable tool for illustrating the technique to his pupils.

A collection of great importance, Rembrandt’s print collection at the Cremona State Library has only rarely been shown to the public, since it is normally kept in the institute’s storerooms, where it is guarded with the care that Abbot Bellò had requested as a condition for donating the collection to the library: the most important exhibition dedicated to the prints was the one organized in 1989, and immediately followed by the critical catalog edited by Angelo Ottolini, which represents to this day the main tool for approaching this collection, which for its importance, consistency and completeness deserves to be widely known.

Rembrandt,

Rembrandt,

The State Library of Cremona traces its origins to the Library of the Jesuit College, which found its place in Cremona in 1600, and the order’s library in turn grew out of the personal library of Bishop Cesare Speciano, who left his books to the Jesuits with the commitment that the library would be open not only to the students of the order, but to all scholars in the city. After the Jesuit order was suppressed in 1773, the library became public, and in 1780 it was opened to the public. Empress Maria Theresa (Lombardy was dependent on Austria at the time), in order to grow the library’s holdings, ordered that duplicates of the Braidense Library be placed there. The major income to the State Library, however, came from the disbursement of funds from the libraries of suppressed convents dating from 1798 onward. Later, the largest accreditation came in 1885, when the State and the City entered into an agreement to deposit at the State Library the Cremona Civic Library, which had been established in 1842 as a result of the legacy of the noble Ala Ponzone family.

Today, the library has a holdings of 2,573 manuscripts (including 200 Latin manuscripts dating from the 12th to 15th centuries, some of them beautifully illuminated), about 550,000 volumes and pamphlets (including 374 incunabula, 6300 sixteenth-century books and 2109 prints, drawings and maps) 5,494 periodicals, including 968 current ones, including 15 daily newspapers. The Library publishes the periodical “Annals of the State Library,” which is now number 56, and the series “Exhibitions” and “Sources and Aids.” Among the treasures preserved in the Library are, in addition to 108 engravings by Rembrandt, a terrestrial globe from 1541 and a celestial globe from 1551, among the very few copies in the world made by Flemish astrologer Gerhard Kremer, lavishly decorated with lapis lazuli, gold and silver.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.