The Cifra 5 electromechanical clock: the Solari revolution

Our “differently young” readers will surely remember the old clocks in train stations: before modern digital monitors, the hours were marked in railroad yards with electromechanical devices that were characterized by fixed digits that changed by clicks. Millennials, if they haven’t experienced them firsthand, have probably seen them in some movie. For decades, those clocks were familiar to those who had to take the train: then, in the 1950s, a company and a designer, both from Udine, wanted to get that particular type of clock into every Italian’s home. Thus was born, between 1954 and 1955, the Cifra 5 electromechanical watch, a creation of Gino Valle (Udine, 1923 - 2003) produced for Solari, a watch manufacturer since 1725, in collaboration with his sister Nani Valle (Fernanda Valle; Udine, 1927 - 1987), an architect by profession, illustrator and graphic designer Michele Provinciali (Parma, 1921 - Pesaro, 2009), and Belgian inventor John Myer.

Solari intended to put into production a watch that would be completely different from those with hands , which at the time were the only solution for those who wanted to have a timepiece in their homes. The idea of replacing the hands with numerals came to Remigio Solari, founder of the Udine-based company: the intuition came a few years earlier and was applied precisely to station display boards and clocks, such as the one at Santa Maria Novella station, designed by architect Nello Baroni, and installed in the 1930s. Solari patented his click system of digits, and then, in the 1950s, thought of bringing it into homes as well.

The Cifra

The Cifra The Cifra

The Cifra The Cifra

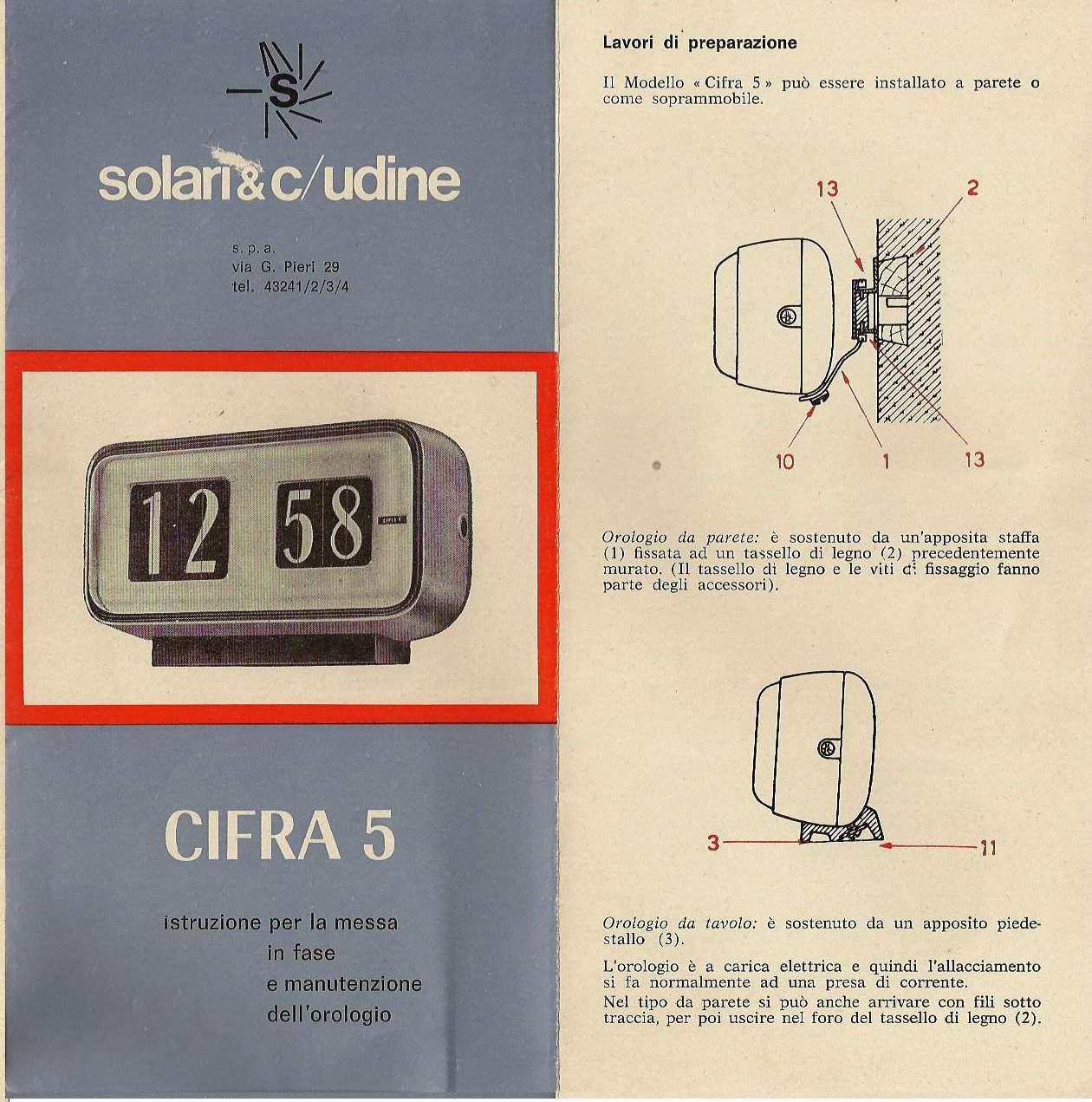

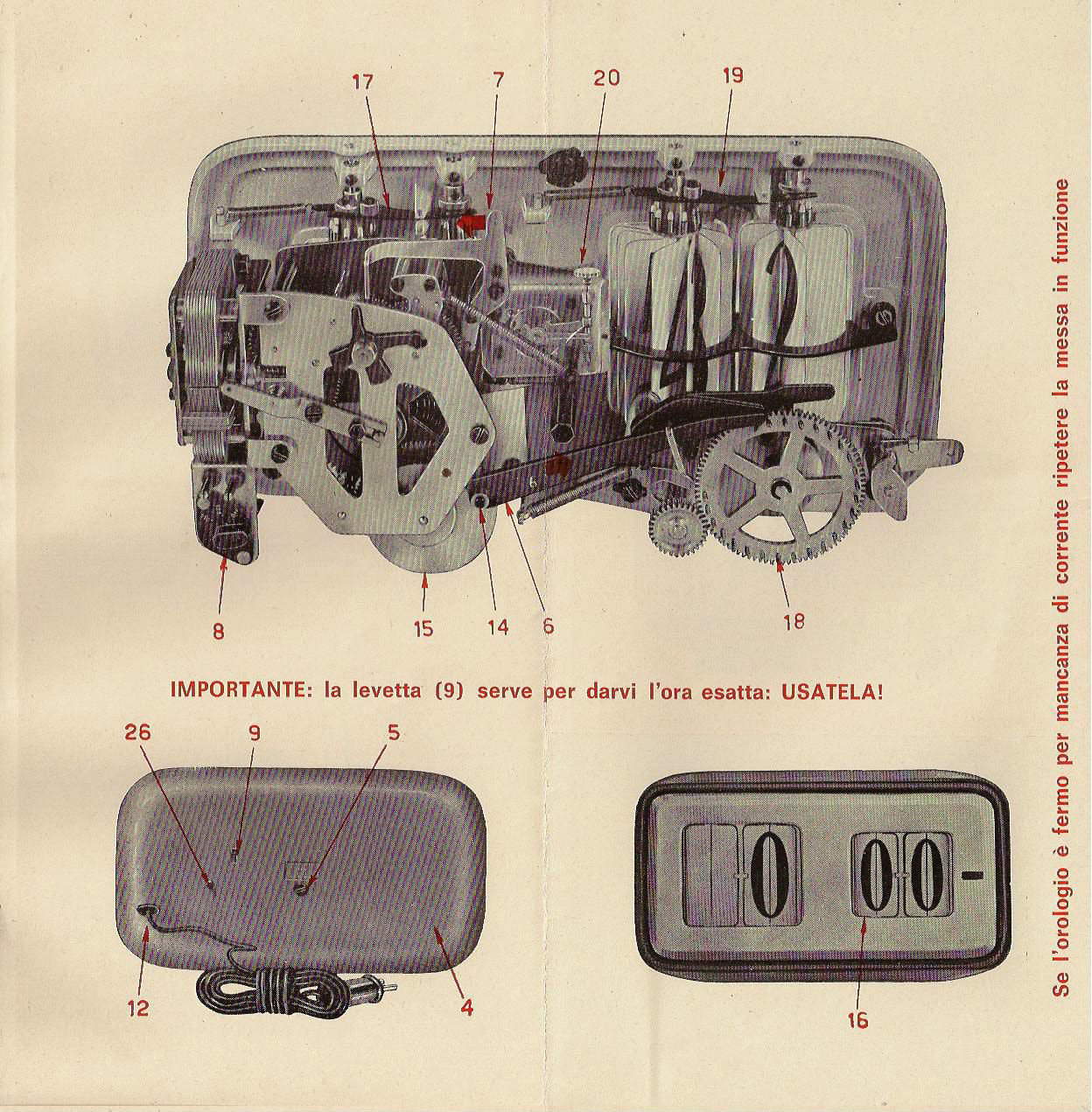

The CifraCifra5 marked the time with digits, exploiting a technology that until then had been used only in industrial or commercial settings. Train stations, for example. Valle therefore thought of a versatile, simple object that could be installed in the home without particular difficulty and that could adapt to different types of environments. The clock’s case had simple lines, and was slightly convex in shape, with the characteristic cream color. The dial showed separate hour and minute numerals. The numbers were engraved on vertical vanes that rotated thanks to a system of rollers inserted inside the case. In order to fit the necessary number of pallets into the watch, it being unthinkable to fit more than fifty for the minutes, Valle enlisted the help of Myer, who suggested the use of the two numbered rollers to take advantage of the number combinations. In the instruction manual for the Cifra 5 , Solari also explained the ways in which the clock could be used: as a wall clock, or as an ornament. In the case of wall installation, Cifra 5 was supported by a bracket attached to a wooden dowel that had to be walled in: both the dowel and the screws to mount it could be found in the kit sold with the clock. Otherwise, the handy pedestal could be used to turn Cifra 5 into an original table clock.

Cifra5 was an electrically wound clock: it therefore had to be plugged in. In order to set the time when first used (or to correct any time shifts: in fact, the instruction manual warned of the possibility of the clock moving forward or backward) it was necessary to operate a special lever (for the minutes) and a harpoon (for the hours), positioned behind the case, which brought the rollers into the correct position. There was also a lever on the back of the watch that allowed the advance of the hour to be stopped. Curiously, a resounding imperative was used in the manual to urge Cifra 5 owners to set the time by taking advantage of the lever (“lever 9 is used to give you the correct time: USE IT!”).

The Cifra

The Cifra The Cifra

The Cifra The

TheThis was an unprecedented innovation that introduced a new way of marking time, and for that reason it was patented, in 1957, in several nations. Before that, however, in 1956, Cifra 5 had been awarded the Compasso d’Oro, with the following motivation: “The Solari watch, which is awarded the ’La Rinascente Compasso d’oro 1956 Prize,’ is the most recent result of a production of electromechanical watches that for years has been concerned with achieving in a unified form the greatest evidence of reading. In this watch, the adaptability of the two positions (support and suspension), the solution of the connection between glass and plastic, the egregious quality of the finish, and the care of the lettering, are among the most evident and qualified aspects.”

From Cifra 5 would later descend a vast family of paddle clocks, starting with Cifra 3, perhaps Solari’s most famous clock, which also entered the MoMA collection, and which stood out above all because it renewed the aesthetics of Cifra 5 in a more modern key, becoming even more versatile and accessible (moreover, it was recently put back into production). Cifra 5 was in turn updated (versions with a calendar were also made: Emera 5, which marked the day of the week, and Dator 5, which also showed the date). A watch perhaps little known to most people today, but one that represents one of the most recognizable images of the 1950s, and above all one that started a small revolution. A product of the company to which we owe the existence of the station and airport tele-indicators that quickly became a widespread presence along communication routes around the world and changed the way the hours were marked. A revolution that started in Udine.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.