The Casanatense Library's collection of scientific instruments.

Astrolabes, compasses, magnets, quadrants, sundials. These are some of the ancient scientific instruments that are part of the collection of the Casanatense Library, which has operated since 1701 in the Dominican convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. The Casanatense Library began early on to replenish its collection of scientific instruments: indeed, it was normal in the eighteenth century for library collections to be enriched with works of art or instruments that had links to the bibliographic heritage.

But in reality, since the Renaissance, the director of the Casanatense, Lucia Marchi, explains, “the library institution was considered a museum of knowledge, in which the book heritage was connected with the various types of funds including artistic works, scientific instruments, archaeological finds, and archival documents so as to become a testimony of the era to be handed down to future generations to keep the flame of knowledge alive.” This virtuous propagation of culture would have been interrupted, Marchi continues, first and foremost by the “law on the suppression of the religious corporations of Rome, enacted by the Italian state in June 1873, in the aftermath of theadvent of Rome as the capital of the Kingdom, whereby the Roman libraries found themselves involved in the organizational arrangement leading to a principle of typological rationalization of content, so that book collections were distinguished from antiquarian, numismatic, and artistic collections,” and later by the “parcelling out of cultural heritage to improve valorization, only declared, but then rarely realized, due to bureaucratic problems and difficulties that the specific institutes have had away in the 20th century due to progressive and appreciable decreases in funding and endemic staff reductions especially in the cultural heritage sector, which have prevented over time the usability of the thousands of works placed in them, and currently often still kept in the countless storage rooms that are increasingly dusty and less and less provided with suitable personnel to bring them to light. Now with the Ministry’s new name, the terminology Culture makes clearer the mission before us, namely the construction of a network that inseparably connects the tangible and intangible testimonies of the past and the present, so that the marvelous beauties we keep in our renovated institutes, thanks also to the use of the increasingly innovative digitization and communication technologies, continue to stimulate the desire for knowledge in the visitors and scholars of the future.”

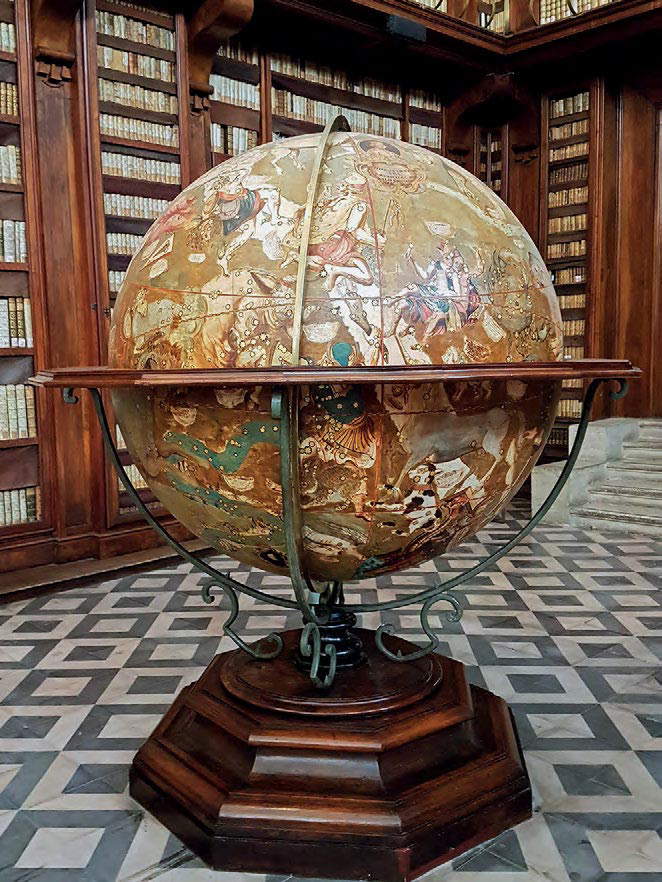

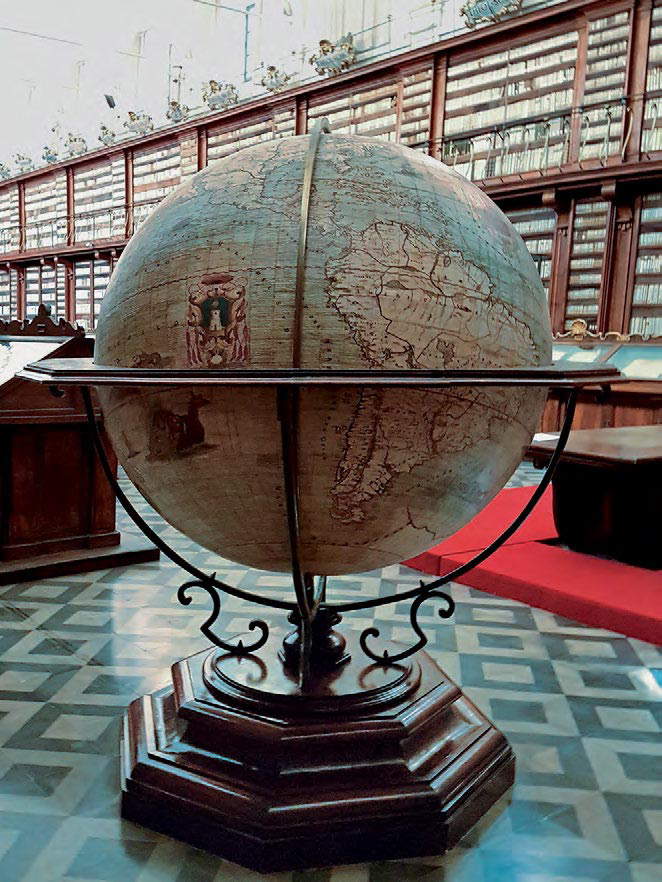

Returning instead to the time of the founding of the Casanatense, it was a widespread idea at the time that a universal library should reflect the trends of its time and at the same time should also project itself into the future: thus, even before March 1703, the master general of the Dominican order, Father Antonin Cloche (Saint-Sever, 1628 - Rome, 1720), who promoted an intellectual and theological revival of the order, had already arranged for the Casanatense to purchase a large armillary sphere from the scientific instrument maker Girolamo Caccia, and had it modified so that it became “more copious and of greater intelligence to make known li due sistemi di Ticone e di Copernico,” so as to be in line with the dictates of the Catholic orthodoxy of the time (the Casanatense sphere in fact takes into account the system of the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, which placed geocentrism in dialogue with heliocentrism: a solution that, still in the 18th century, was accepted by a Church that was interested in studies of the universe). Subsequently, in 1715, Cloche himself ordered the purchase of two globes, one terrestrial and one celestial, made in ink and painted in tempera by the cartographer and cosmologist Silvestro Amanzio Moroncelli (Fabriano, 1652 - 1719), abbot of the Silvestrini congregation of the church of Santo Stefano del Cacco: the purchase of the globes was to supplement the library’s existing holdings on astronomical and geographical themes. Incidentally, the globe also features a portrait of Cloche himself.

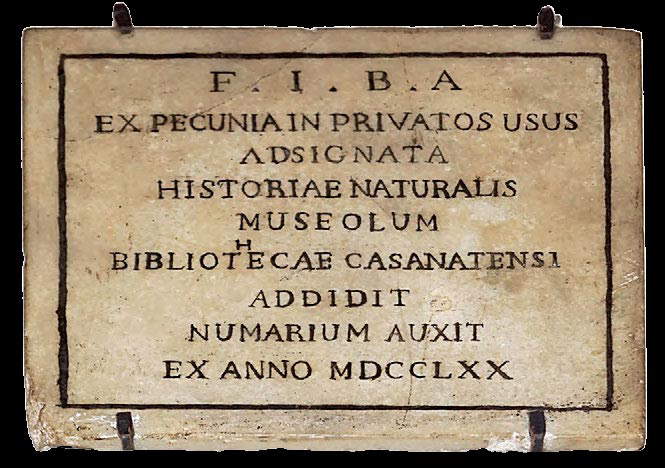

The Casanatense’s collection of scientific instruments was further enriched with Father Giovanni Battista Audiffredi (Saorgio, 1714 - Rome, 1794), astronomer, bibliographer and prefect of the Casanatense from 1759 to 1794: Audiffredi was responsible not only for the expansion of the bibliographic holdings but also for the acquisition of astronomical and scientific instruments, numismatic funds, precious gems and even works of art, according to the Enlightenment vision of the time. The scientific interests Audiffredi cultivated brought him close to intellectuals of the time such as Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Girolamo Tiraboschi, and Angelo Maria Bandini, and led him to make the Casanatense one of the most distinguished cultural institutions of the time: it was under his prefecture that the Casanatense was endowed with a “Small Museum of Natural History” (l’historiae naturalis museolum), the founding nucleus of the library’s current museum itinerary. Audiffredi also had a passion for the natural sciences, numismatics, antiquarianism and anatomy: “it is said,” Lucia Marchi explains, “that in a loggia of the Convent of the Minerva he had set up an astrological cabinet for his observations and studies on the passage of Venus and Mercury, eclipses and motions of the moon, the theory of comets and solar parallax, related in some of his works published between 1753 and 1770. And, despite the fact that he portrayed himself as an ancient dabbler in astronomy, and considered his works astronomical bagatelles, he was actually appreciated for his precision in calculations and accuracy of astronomical surveys to the point that the Jesuit Giuseppe Ruggero Boscovich, a supporter of Newtonianism at the Roman College and an astronomer of European renown, had described him as ’diligent observer of’ celestial phenomena,’ and the famous French astronomer Joseph-Jerome de Lalande, who had met him while visiting the Casanatense in one of his Roman sojourns, considered him a ’habile astronome.’”

The instruments that Audiffredi used for his research probably flowed into theastronomical observatory that had been built in the 19th century by Father Alberto Guglielmotti, Casanatense librarian from 1850 to 1859, in the College of St. Thomas Aquinas at Minerva: in fact, the Book of Reasons records the purchase of a lot containing also scientific objects with funds from the Casanate inheritance in 1770, presumably for the purpose of enlarging the museolum built at the Casanatense by Audiffredi, entirely at his own expense, of which modest evidence remains in the library.

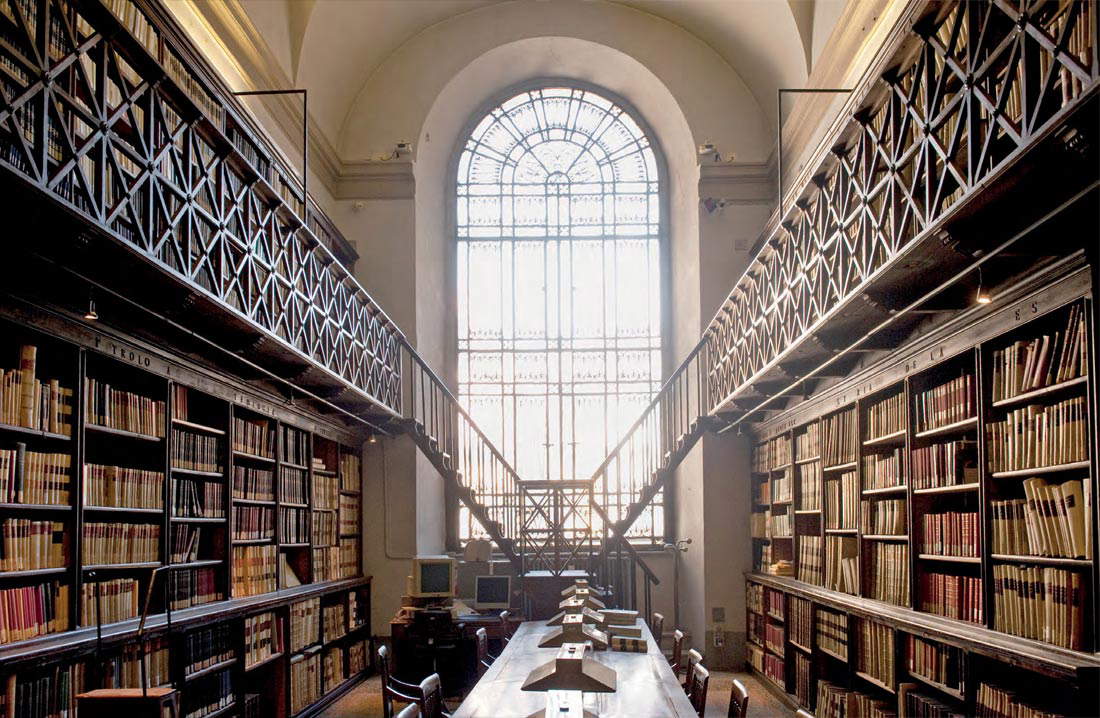

The visitor who enters the Casanatense Library today will find many of the scientific instruments collected since the foundation of the institute. These objects include, of course, the armillary sphere purchased by Cloche in 1703: it has a circumference of almost four meters and is a depiction of the celestial sphere according to ancient astronomy. In the private writing governing the purchase of the sphere, also preserved at the Casanatense, we read that the armillary sphere is “composed of two smooth iron half-circles with vn’iron rod attached to the said, quali cerchij et asta di ferro attaccata seruono per posamento e supporto di detta sfera sopra de quali cerchij è fermato l’Orizzonte d’ottone... in una con il suo meridiano e Zodiaco con li due Colluri e Legature li due Tropici, due Cerchij Polari e tre Cerchi de’ Pianeti Superiori.” Also exhibited then are Moroncelli’s two globes, the grandeur of which can easily be inferred from the phrase that the last Dominican prefect, Pius Thomas Masetti, uttered to recall that “to let them in it was necessary to widen the entrance door.” Both the armillary sphere and the two globes occupy today the spaces of the Monumental Hall of the Casanatense, designed by the architect Antonio Maria Borioni (documented between 1685 and 1727), and which we see today not too far from how it was set up in the eighteenth century, since in later times the curators of the Casanatense always tried to preserve its integrity.

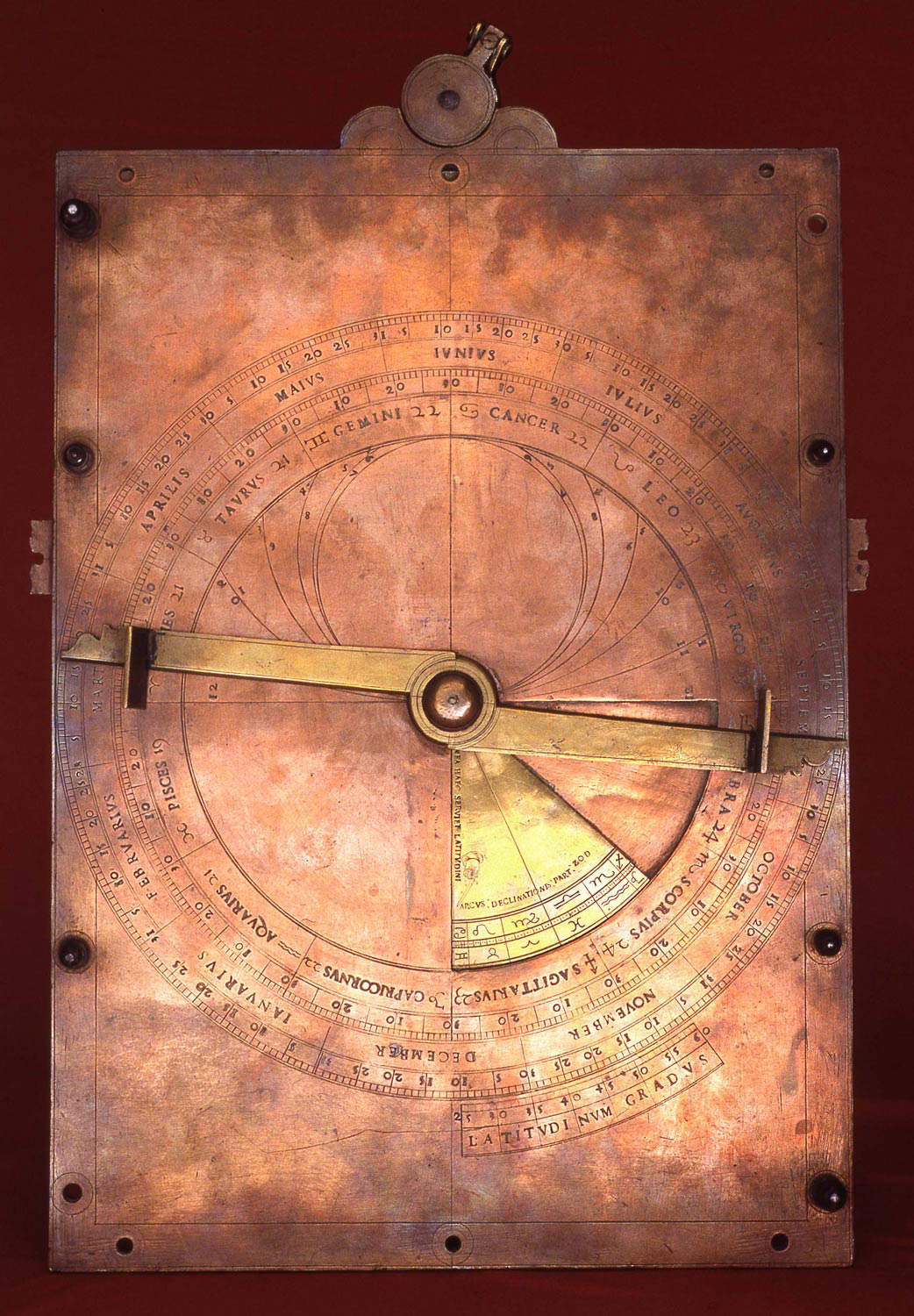

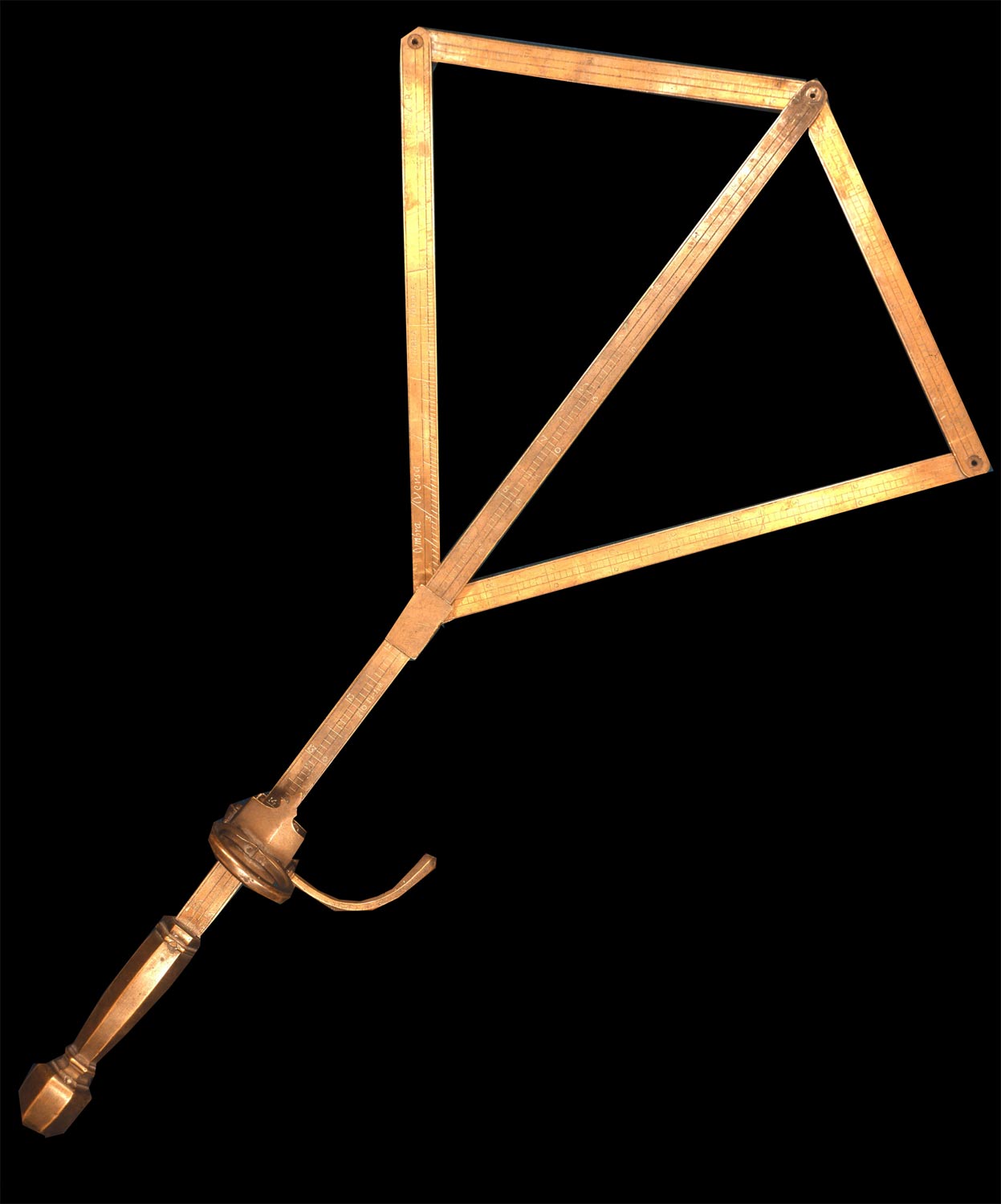

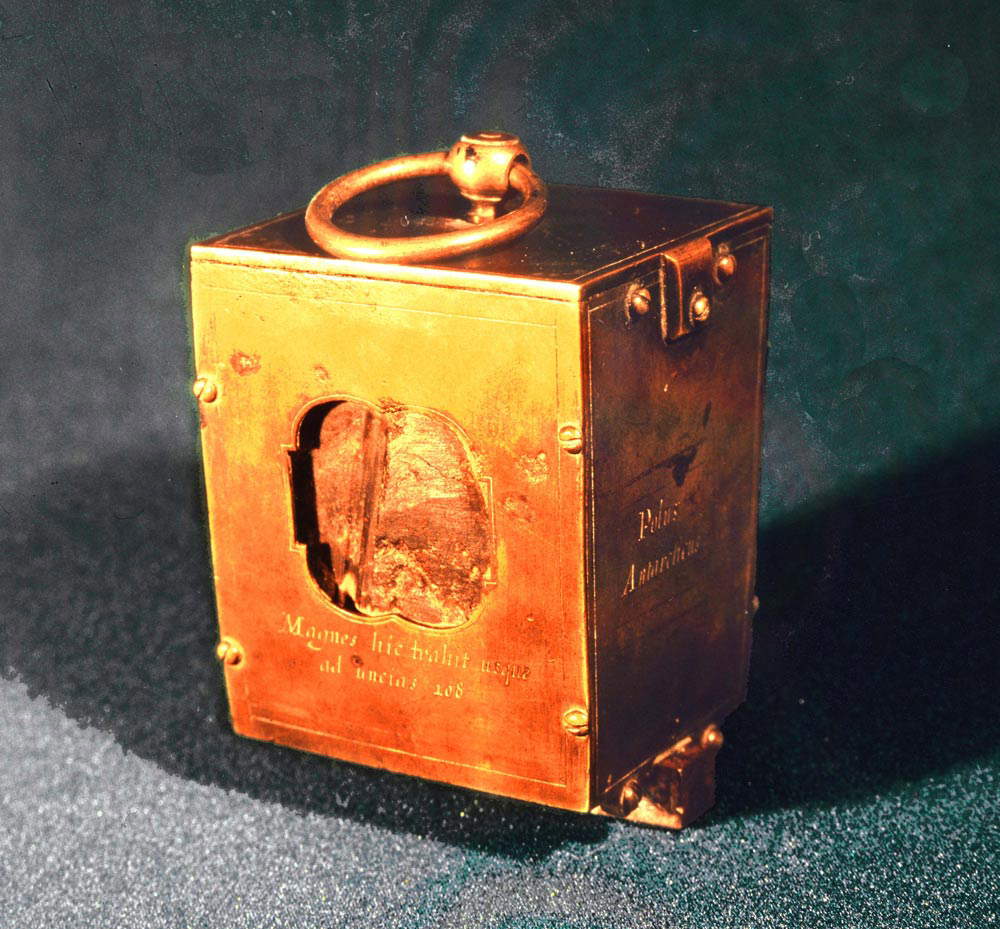

Still, the public, in the Casanatense’s museum itinerary, can admire a Latin radio (an ancient instrument for measuring distances and heights, invented in the 16th century by the condottiero Latino Orsini), in brass, from the early 17th century, and then again an original object in copper and brass with valuable decorative engravings, which was used to measure time, whose verso is the same as the verso of an astrolabe, presumably from the 16th century. Also, a brass cursor dial from the 14th century, of German manufacture; a brass sundial cup clock from 1626, of Italian manufacture; a brass topographic compass from the 17th century; three wooden dividing compasses with metal tips from the 18th century, of which the largest large could be identified as an instrument in use by the encyclopedic prefect, as it appears in Audiffredi’s oil portrait; and finally, a cosmoplane (i.e., a planar celestial globe) manufactured in Paris in 1768 to the design of Abbot Jacques Francois Dicquemare (Le Havre, 1733 - 1789). There is also documentation of the purchase in 1765 of a natural magnet included in brass casing. Completing the selection are a wheeled parallel ruler, manufactured in London by the renowned Dollond manufacturer and a coin weigher, both in the early 19th century.

Today, the Casanatense Library aspires to resume the never-ending thread of communication that exists between the various types of heritage, and rediscover interesting links that led to the essay published in the volume Rischiarare il vero, rilevare il bello. Histories and Models of Protection and Enhancement of Cultural Heritage in the series Notiziario del Portale Numismatico dello Stato: a study that, thanks also to the intervention of the Director General for Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape, Federica Galloni, and the Director General for Libraries and Copyright, Paola Passarelli, and to the availability of the Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, obtained the special print follow-up dedicated The Casanatense Library: the Museum Unveiled. A Guide to the Collections, and is presented as a fundamental essay thanks to which one can understand the various collections that are not purely book-related (thus the archaeological, numismatic, and scientific collections) present in the prestigious institution, and, in particular, the intimate links that inseparably connect them. “This new storytelling of the Library in the third millennium,” concludes Director Marchi, “has created an indissoluble link between the properly museum route leading to the Monumental Hall and the bibliographic route that finds its natural landing place in the three Reading Rooms of the twentieth-century section, currently updated in line with the needs of users of thedigital era, where one can also access them virtually thanks to the adoption of Minerva Access, and in which one has the possibility of studying indiscriminately from the oldest manuscripts to the newest databases, thanks to the special devices inserted in each workstation and to the network that is present throughout the entire surface of the institute.”

The Casanatense Library

The Casanatense Library opened in 1701 in the convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome: it was established by the fathers of the Dominican order at the behest of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate (Naples, 1620 - Rome, 1700). To realize it, architect Antonio Maria Borioni designed a special building in the area of the Minerva cloister: the library opened housing the cardinal’s rich book collection, which numbered more than 25,000 volumes. Subsequently, thanks in part to the network of connections that the curators of the Casanatense were able to build with the European book trade, the library was soon enriched with books, works of art, scientific instruments, archaeological finds, ethnological material, and coins. The greatest expansion of the collections occurred with prefect Giovanni Battista Audiffredi, who opened the museolum, the first nucleus of the museum itinerary that can still be visited in the library today. Management of the library passed from the Dominicans to the state in 1884: after having long been administered by the Ministry of Education, today the Casanatense is a peripheral institute of the Ministry of Culture.

Currently, the Casanatense holds about 400,000 volumes including manuscripts, incunabula and printed books: of these, about 60,000 are still preserved in the Monumental Hall. The manuscript collection, which was formed mainly through the acquisition work of the Dominican fathers (Girolamo Casanate in fact owned very few), covers a time span from the 8th to the 20th century, and consists of about 6,200 volumes of different formats. The collection of incunabula (about 2,000: among these of notable interest are the special illuminated incunabula, including an edition of the Divine Comedy) was also largely formed in the 18th century, thanks mainly to the work of Gian Domenico Agnani and Giovanni Battista Audiffredi. Then again, among the treasures of the Casanatense are the graphic collection (with many prints by German and Flemish artists, from Albrecht Dürer to Hans Baldung Grien, from Hendrik Goltzius to Lucas van Leyden), the scientific collection, the archaeological collection, the periodicals collection that includes 1.850 titles, the edicts and notices collection (about 80,000 documents), the music collection, which includes the manuscripts of Nicolò Paganini collection with 90 mostly autograph pieces, the nucleus of Ottorino Respighi’s papers, and a collection of printed music librettos with about 1,900 copies.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.