The Carta de Logu, the law in Sardinia in the late fourteenth century

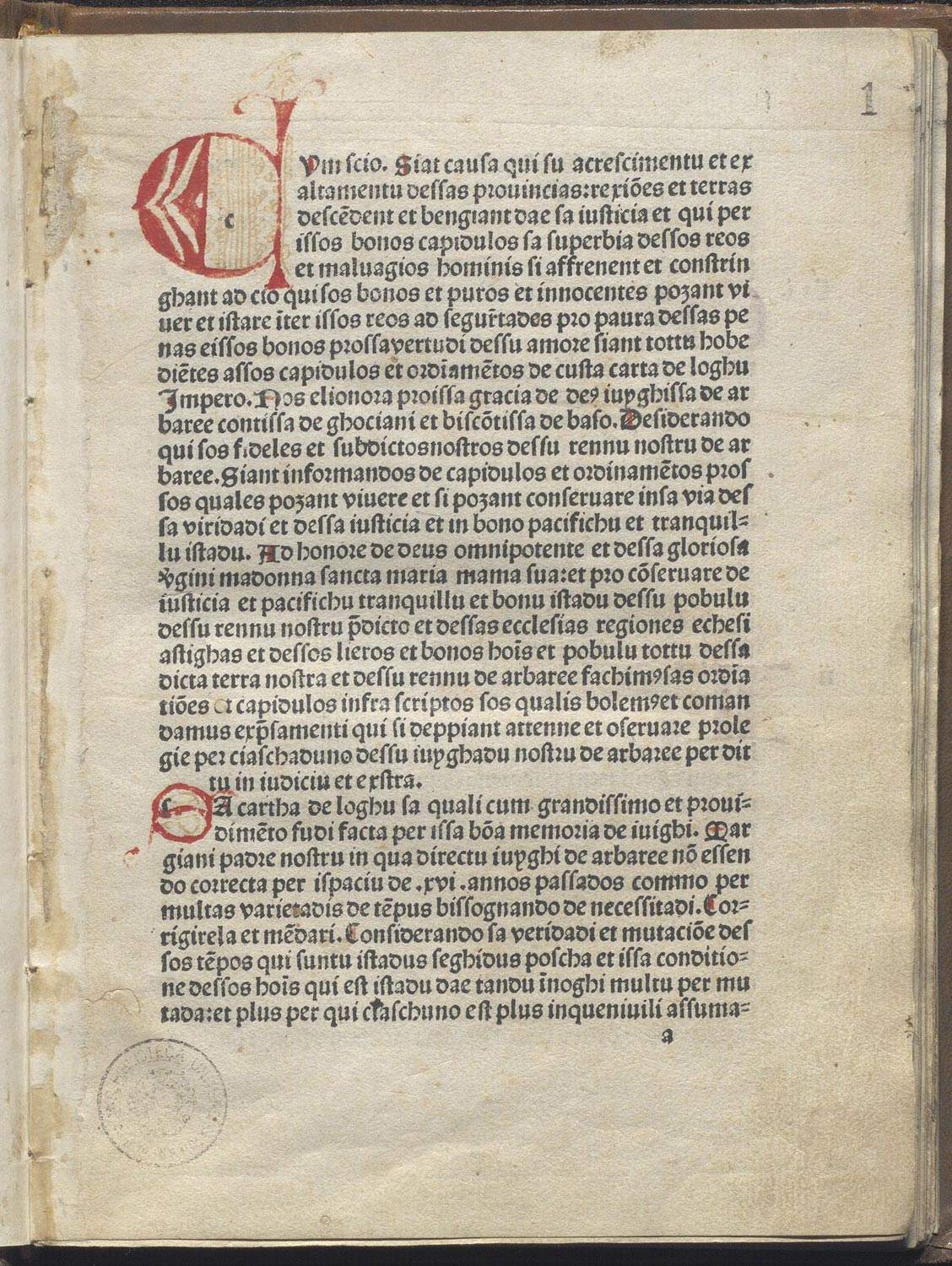

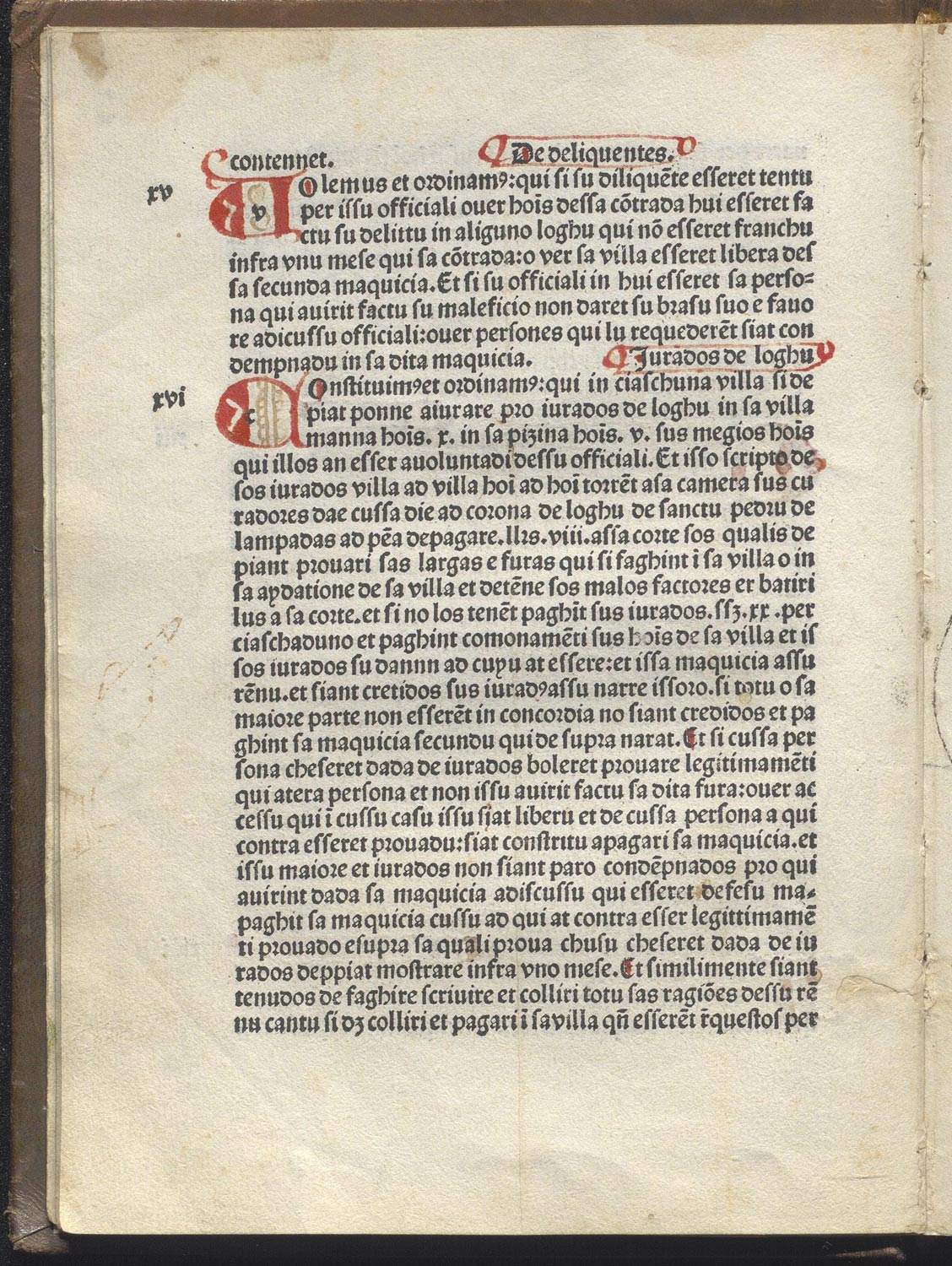

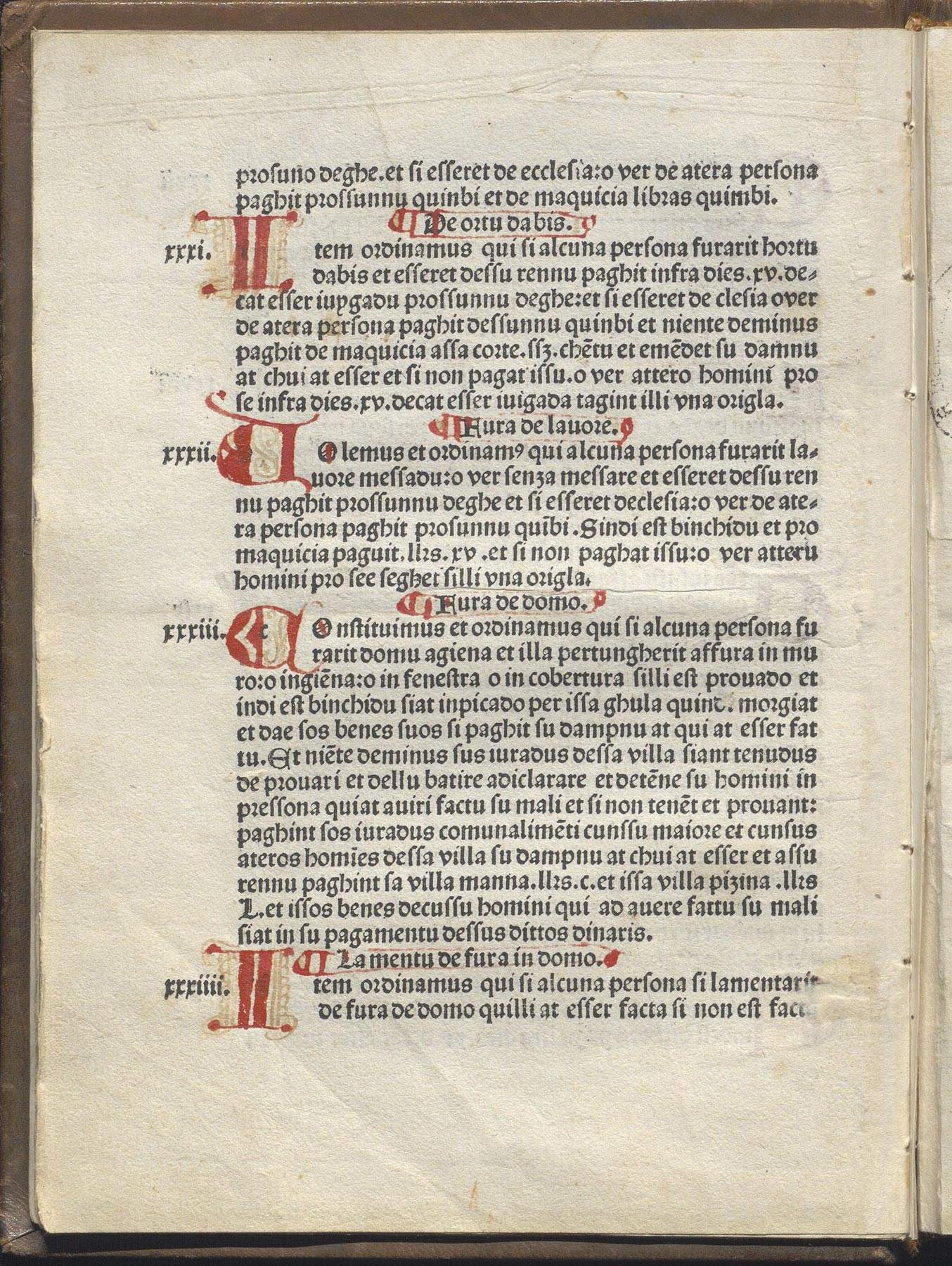

Few figures in ancient Sardinia are as well known as that of Eleanor of Arborea (Molins de Rei, c. 1347 - Sardinia, 1403), who was giudicessa regent of Arborea from 1383 to the year of her death: daughter of Mariano IV, himself one of the most important figures in 14th-century Sardinia (the giudicato of Arborea, under her rule, expanded to cover almost the entire Sardinian territory), is best known for issuing the Carta de Logu (“Charter of the Territory”), a legislative code whose validity was recognized and extended by the Aragonese, in 1421, to the whole of Sardinia, and which remained in force until 1827, when the Felician Code, which was to replace it, was issued. The legal and administrative rules contained in the Carta de Logu (its manuscript, incomplete, is preserved at the University Library of Cagliari, but there are also nine printed works and a Pisan translation: the Cagliari library preserves one of the two extant incunabula, the other is at the Royal Library of Turin) are inherited from Roman and Byzantine jurisprudence, and set laws derived from the orders issued by earlier island judges.

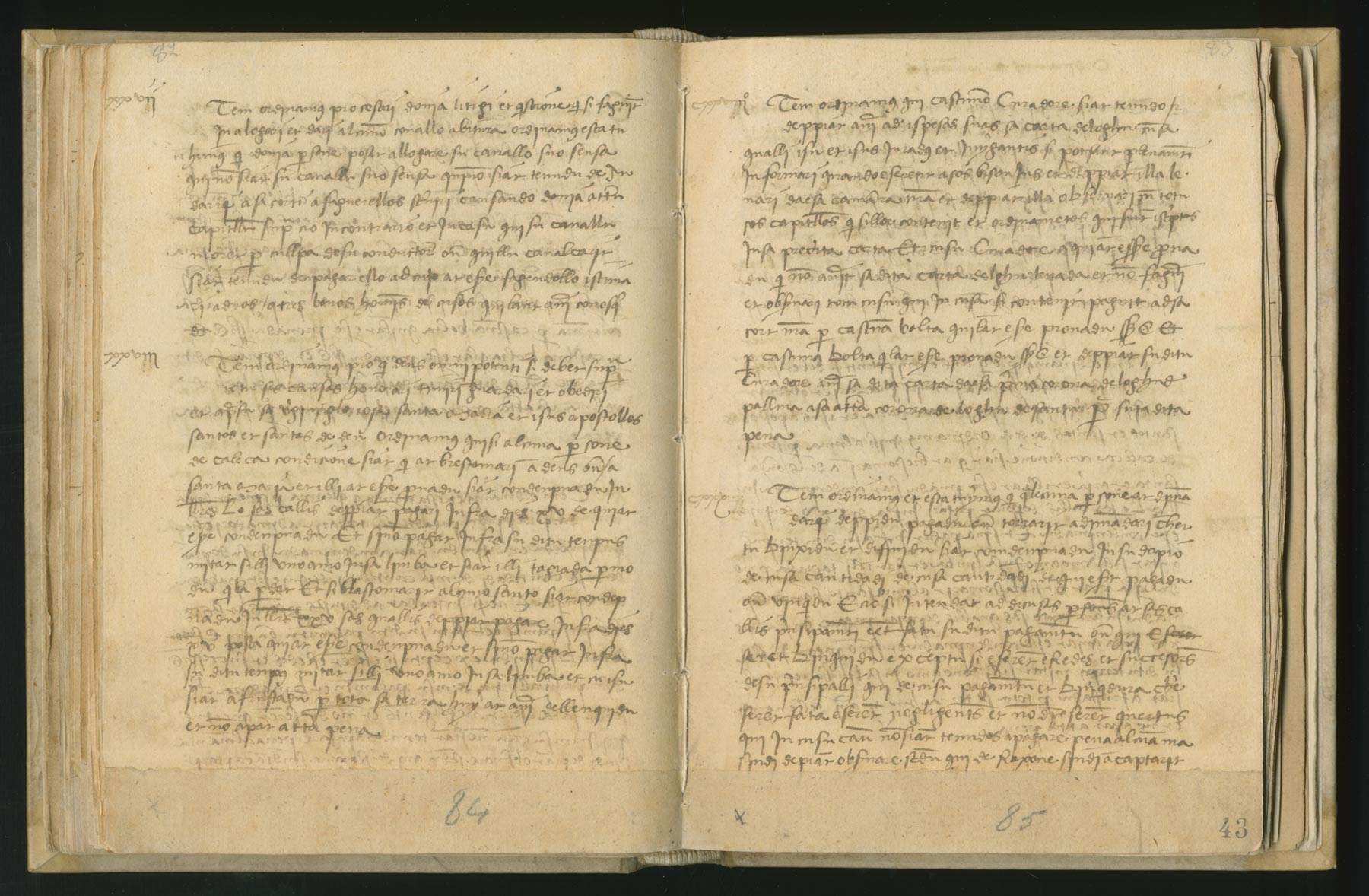

In particular, the primitive core of laws that make up the Carta de Logu was promulgated as early as Mariano IV, who issued a Rural Code in 1337, which was later renewed: it is a code of twenty-seven chapters with regulations on agricultural activities (vineyards in particular) and animal husbandry. A few decades later, between 1365 and 1376, Mariano IV himself had the Civil and Penal Code of the Judicature prepared, a set of regulations in 132 chapters (probably compiled by the jurist Filippo Mameli) that constitutes the largest part of the Carta de Logu. It was only with Eleanor, however, between 1388 and 1392, that Mariano’s two legislative cores were combined into a single Carta de Logu, updated, and promulgated.

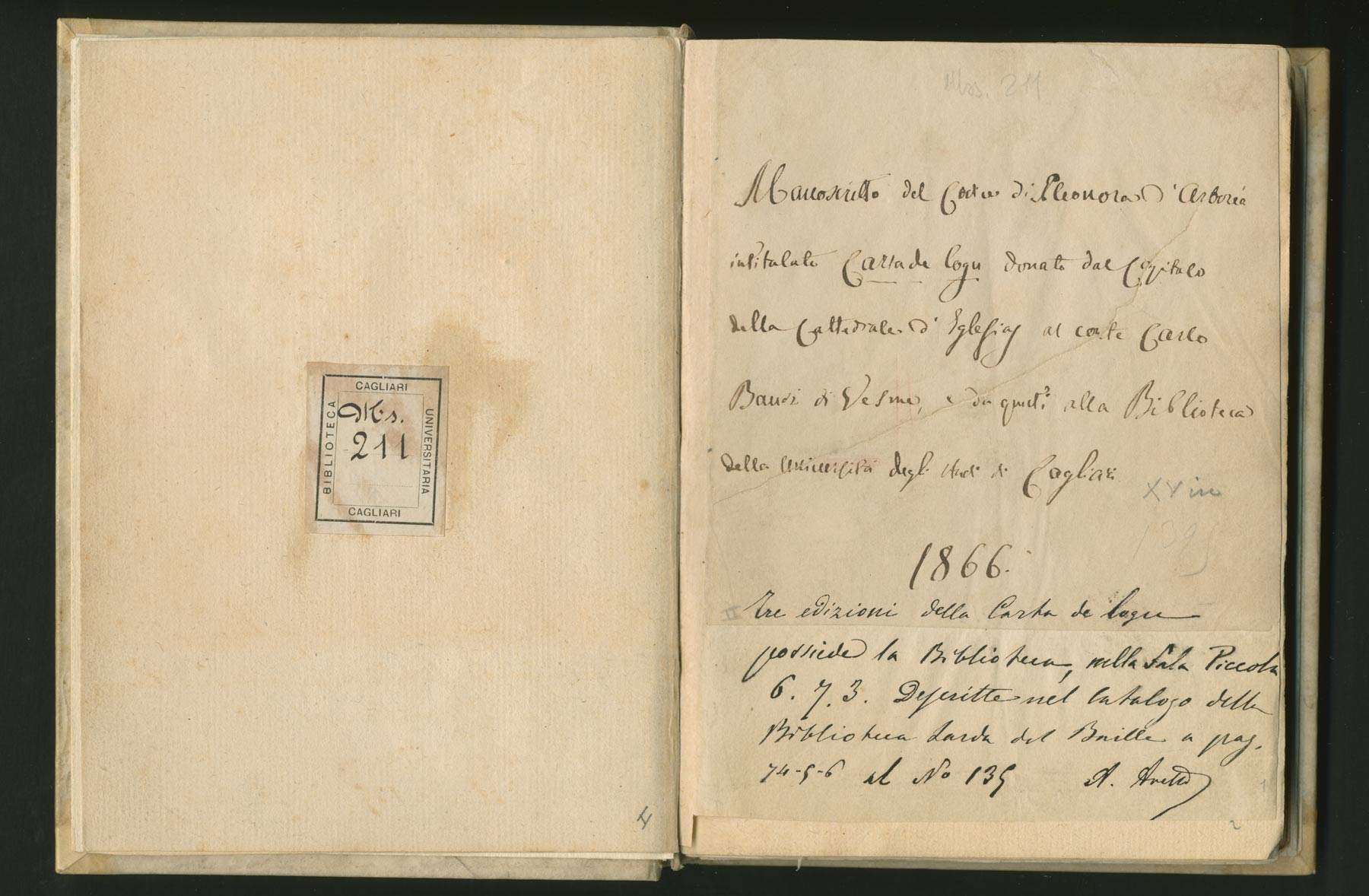

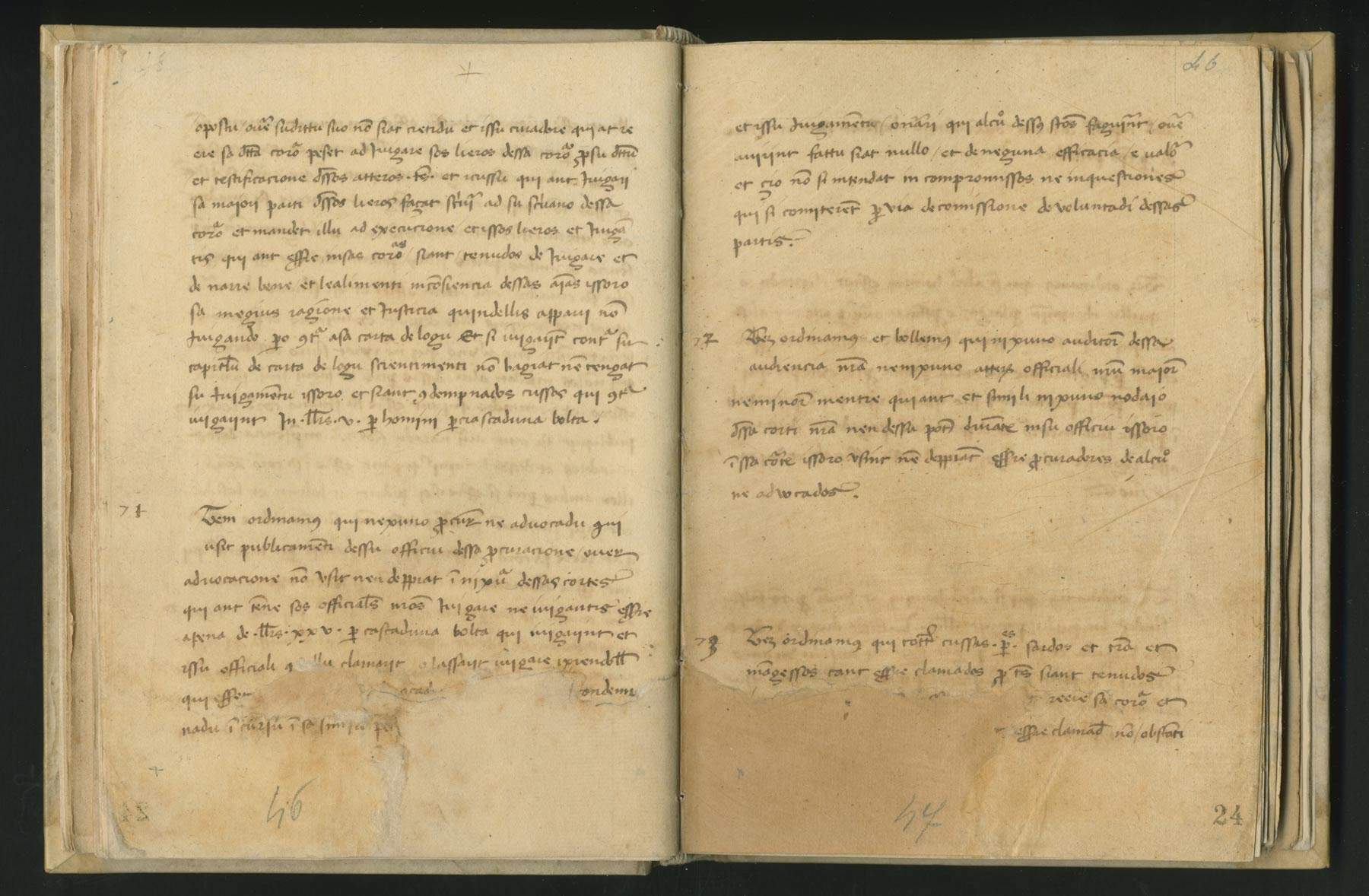

The manuscript preserved at the Cagliari University Library is said to be the work of at least two copyists, and before passing to the Cagliari University Library it was kept at the Cathedral Chapter of Iglesias. We do not know the original codex, nor have any coeval copies been preserved, although scholar Eduardo Blasco Ferrer has speculated that the Cagliari codex was drafted between 1376, the year to which the conclusion of the Rural Code dates, and 1392, the date of the last promulgation of the text. “The two hands that succeed each other in the witness,” wrote philologist Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, “would correspond to two scribes, officials of the Sulcitan municipality in charge of preparing a copy of the forthcoming Arborense legislation, perhaps to be compared with the Pisan norms already in force there [...], or previously applied in the extinct Giudicato of Cagliari.” According to a more recent study by Giovanni Lupinu, the codex in the Cagliari University Library was actually copied in the early 15th century.

However, the Carta de Logu has a multiple tradition, since it is known on the one hand through the manuscript and on the other from prints based on the editio princeps (the first printed edition). In fact, Lupinu writes, the code preserves "an earlier drafting than that given in the prints, which took shape only afterwards, integrating, without, however, fully harmonizing them, pre-existing normative sections, especially related to the life of the fields, for otherwise it would have to be admitted that the code hands down a later and foreshortened drafting of the Carta de Logu." The code in fact does not include the Rural Code, a circumstance probably attributable to the fact that Eleanor of Arborea did not want to include it entirely in the Carta de Logu.

The enactment of a general code had become necessary to overcome some of the problems that characterized the judicial system of the Judicature of Arborea: the often uncertain and arbitrary application of the law, the excessive legislative fragmentation due to the episodic nature with which certain areas were regulated (and where there was no law they proceeded according to customary usage), the need to ensure certainty of punishment, the need to endow the giudicato with laws that were easy to understand, so much so that the Carta de Logu was enacted not in Latin, but in Arborean Sardinian, in order to allow the widest possible understanding. So much so that the code immediately begins with Eleanor’s statement that, recalling how the first version of the Charter had been issued by her father Mariano V, the purpose of the laws contained in the charter was to “maintain justice” (“pro servari sa iusticia”) in view of the “accretion” and “elevation of the provinces, kingdoms and lands.” Therefore, noted scholar Giampaolo Mele, "from the very incipit of the Carta de Logu d’Arborea, emanates the noble sense of the ’public good’ that was breathed in the Giudicale court."

What are some of the legislative contents of the Carta de Logu? For example, the code regulates time off from work by listing vacation periods and holy days, days during which even public meetings had to be suspended (there was a vacation period from June 15 to July 15, one from September 8 to October 1, and then all religious holidays, including patron saints’ days). Penalties for different offenses are then listed: in particular, capital punishment was provided for the offenses of offense against the Lordship, murder, poisoning, robbery of houses, and burning of houses. In addition, the death penalty was provided for cases of recidivism. For other minor crimes, mutilation was also provided (the body parts affected were the right hand, foot, tongue, eye, and ear): for example, the ear was cut off for those who stole horses or oxen, while an eye was put out for those who were fined for stealing from church and could not pay. For those who blasphemed God or Our Lady and could not pay the relevant fine of 50 liras, there was provision for the cutting off of the tongue (the punishment for those who could not match the 25-lira penalty for blasphemy against the saints was milder, however: flogging and a hook driven into the tongue). Giampaolo Mele noted how “the harshness of the penalties” is “also well present in Eleanor’s Code to protect women and their property.” rape, in cases where a married or betrothed woman was raped, or where the rape involved the loss of virginity, was punished with a fine of 500 liras and, in case of insolvency, with the cutting off of the foot, while on the other hand for rape against an unmarried woman there was a fine of 200 liras with an obligation to marry the woman, but only in case the woman consented, and otherwise the offender was obliged to provide for the marriage according to his possibilities (in case of default, there was always the cutting off of the foot).

Since the Carta de Logu is one of the most interesting and wide-ranging legislative codes of the 14th century, attention to it has always been very much alive, not least because of its ability to bear witness to what life was like in 14th-century Sardinia, to give us a picture of the personality of Eleonora d’Arborea, and to be matter for those studying the Sardinian language.

The University Library of Cagliari

The origins of the University Library of Cagliari date back to 1764, when it was established in 1764 with the Constitutions for the reform of the University and housed, at the behest of King Charles Emmanuel III of Savoy, in the building above the Balice Bastion: designed by the military engineer Saverio Belgrano di Famolasco, the building was imagined to house the University, the Theater and the Tridentine Seminary. A special conservation and reading room called the “Sala Grande,” known today as the “Sala Settecentesca,” was reserved for the Library, furnished with elegant lacquered and gilded shelving. Instead, it dates back to 1792 when it was opened to the public. In later years the Library was granted new spaces, including the Chapel, equipped with a barrel vault and richly frescoed and now used as a room for the preservation and consultation of rare materials.

The original nucleus of the Cagliari University Library consisted of the sovereign’s private library, funds belonging to the suppressed Jesuit Order and copies of the works that professors were required to provide. Today, the Library holds more than 600,000 bibliographic units including 6,103 manuscripts and autographs including 568 codices, 238 incunabula, 5,318 cinquecentine, 5,227 newspaper and magazine titles, 6,500 drawings, prints, maps and postcards, more than 15.000 documents in non-print media, including microfilms of all 19th-century Sardinian manuscripts and newspapers, the largest and most complete collection of bibliographical material from Sardinia and about Sardinia, and a large and organic collection of highly interesting ancient Spanish material.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.