The collection belonging to Carlo Pepi is an immense collection of works, consisting largely of paintings and drawings, the outlines of which are certainly not easy or at least immediate to trace. It is arranged in two villas in the province of Pisa, in Crespina, amidst countryside and hills, there where you would not expect to find so much art, but which in fact has always been a destination for vacation and retreat, and its Arcadian landscape attracted countless artists as well, particularly the Macchiaioli and their heirs, including Silvestro Lega, the Tommasi, Adolfo and his brothers Angiolo and Ludovico, Francesco and Luigi Gioli (born nearby, Giorgio Kienerk, but also Anchise Picchi, and who knows who else). The collection is visited in the frequent appointments that the owner, Pepi, animates by taking visitors on a discovery of his home and the stories it brings.

A unique, alienating, disorienting and unconventional experience, adjectives that, after all, also match the creator of this immense collecting effort, that extraordinary and picturesque character who is Carlo Pepi, and one does not want out of malice to read the attribute “picturesque” as something derogatory, but anything but, and this will be understood later.

By now Pepi’s name is familiar to many: in fact, the collector has made a name for himself as a hunter of forgeries, with a self-taught education and apparently an innate talent, an attributionist’s eye that Pepi did not lend to connoisseurship, but employed to ferret out works that were fraudulently being placed in art circuits under high-sounding names. Long is the list of spectacular insights he amassed, debunking and spoiling the party for counterfeiters, greedy dealers and unscrupulous collectors, which earned him more than one accolade and much bitterness, as his competence was not infrequently questioned as well as his merits silenced or denied. But from memory, Pepi was always right, even when he was lashing out against important experts, esteemed curators, and imposing entities operating in the art exhibition sector, as happened often to defend one of his favorite artists, Amedeo Modigliani, of whose Birthplace in Livorno he was also president.

Pepi’s character is either loved or hated, hailed by many as a voice of the people who launched himself against giants and experts, hated and opposed by others, who disliked the forays into the field of art and the ostentatious confidence of one who had no academic qualifications. A multifaceted and complex personality that always ends up polarizing judgments, and that just as often catalyzes interest but ends up diverting it from his collection, which is just as fascinating, and which proves, if there was still a need, that Pepi is certainly no improviser in the art world.

This is probably the most voluminous art collection in Tuscany and beyond. But the numbers don’t seem to please Pepi too much, which is doubly absurd, first of all since one is usually sadly used to interface art, as indeed virtually all aspects of life, with purely quantitative interests: how many works are there? How much are they worth? Which one is worth the most? These are just some of the most frequently asked questions in museum circles. Moreover, Carlo Pepi is an accountant and is supposedly very familiar with numbers. But Pepi does not like to talk about values and prices; his collection is certainly valuable, but it was put together out of documentary scruples and pure enjoyment, and the collector’s admittedly not infinite capital, which has been financially troubled several times by his passion, has steered his choices toward more affordable works. This has not prevented him from putting together some masterpieces, many valuable historical records, interesting pieces of little-known painting, which with extreme naturalness are arranged next to even works of decidedly inferior quality by artists whom Pepi sometimes refers to as “imbrattatele.”

This endless collection has been put together by Pepi throughout his life. “My life motto? Buy one work of art a day,” said Peggy Guggenheim, but Carlo must have upped that daily number significantly.

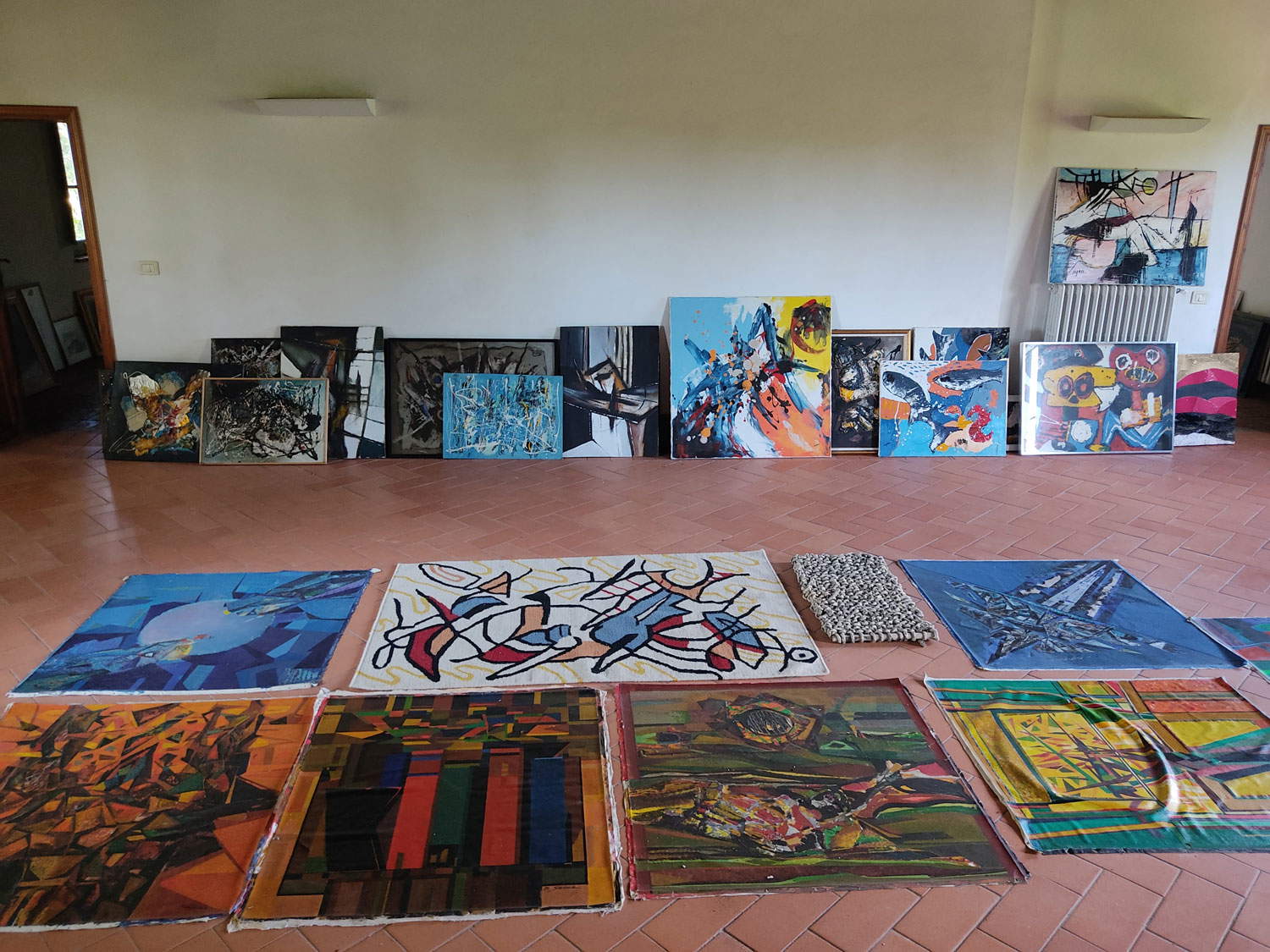

A visit to the Pepi Collection begins in an old and monumental farmhouse in the center of Crespina, Villa Montelisi. This is home to the twentieth-century nucleus of works; all the rooms are completely filled with paintings, some attached to the walls and some stacked in every piece of furniture and nook and cranny. Pepi bought most of these works directly from the artists, whom he frequented, becoming friends with them, supporting them even when ignored by the market and critics. Pepi was always attentive to the artistic movements and their protagonists in the Tuscan scene, but particularly in Livorno, a city that he said gave birth to great artists, even if most of them are still little known if not forgotten today.

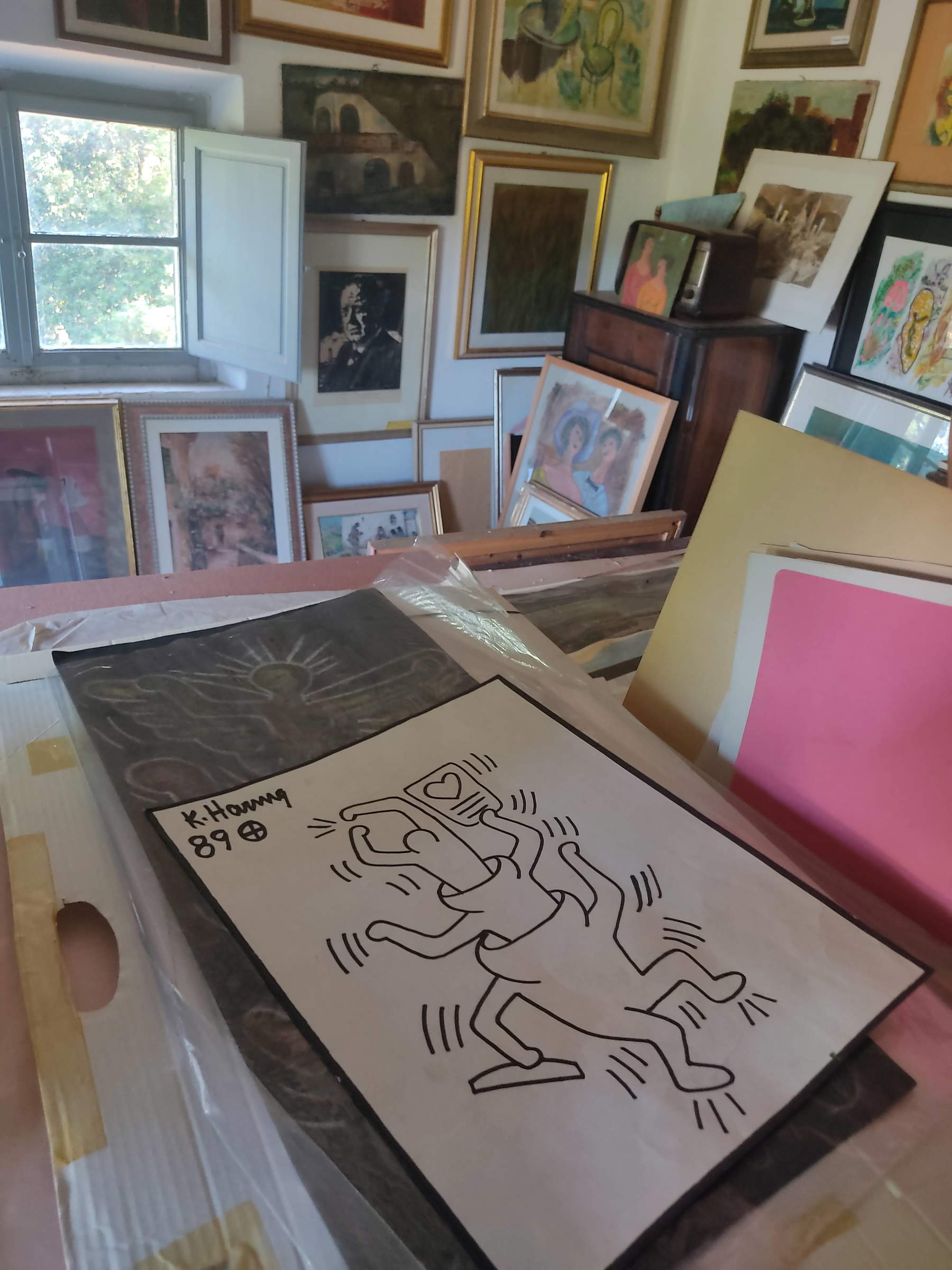

Of Mario Nigro, Pepi remembers being present at his bedside: he was the artist with a background as a chemist and pharmacist, who in his last hours consoled himself by being included in an art catalog along with the most important artists of the 20th century. Instead, with emotion Pepi speaks of Renato Lacquaniti, a politically committed artist affiliated with the Anarchist Federation, whose essays the collector has of virtually all his production, incredibly eclectic and often ahead of his time. Also of the same political persuasion is Renato Spagnoli, who is also abundantly present in the collection, as are the other protagonists of the Atoma group: works by Voltolino Fontani and the artists of the Eaista movement, who became the bearers of a poetics strongly impressed by technology and the nuclear threat, continually pop up in the rooms of the building. Also, some works by Zeb, the Leghorn street artist who mysteriously disappeared, Giovanni March, heir to the Labronian tradition, Bruno Secchi, Antonio Vinciguerra, Jean Mario Berti, Chevrier, Alvaro Danti, and Osvaldo Peruzzi. Labronians are numerous, but not the only ones: conspicuous are the graphics of Giuseppe Viviani, the works of Vinicio Berti, Paolo Scheggi, Mino Trafeli, but also Keith Haring, whom Pepi met in 1989 when he made the work Tuttomondo in Pisa. An entire bedroom, including the bedchamber, is completely cloaked in the shocking woodcuts of Lorenzo Viani, an artist from Viareggio, among the greatest protagonists of the first half of the 20th century, a proponent of an art of social denunciation and expressionist slant.

But some of the most valuable pieces are in the other building, the family villa, more secluded than the center. Here the 19th-century nucleus is preserved above all, which Pepi put together with great foresight, orienting himself toward the makers of the Macchiaiolo movement and its heirs, whom the market made accessible and in particular to drawings and graphic works, whose price was even more meager. Of these, Pepi appreciates the peculiarity of allowing one to see a work in the making, in its conception or study, far from certain easy effects that connote other more finished and commercial productions. Countless drawings, engravings, sketches and all other kinds of notes are arranged everywhere or hidden in drawers. Pepi owns much of the engraving work of Giovanni Fattori (although years ago he suffered a major theft) but also graphics by all the other protagonists: splendid ones by Abbati, Zandomeneghi and Signorini, even two drawings by Modigliani, one of which is the masterful lapis of Sitting Woman.

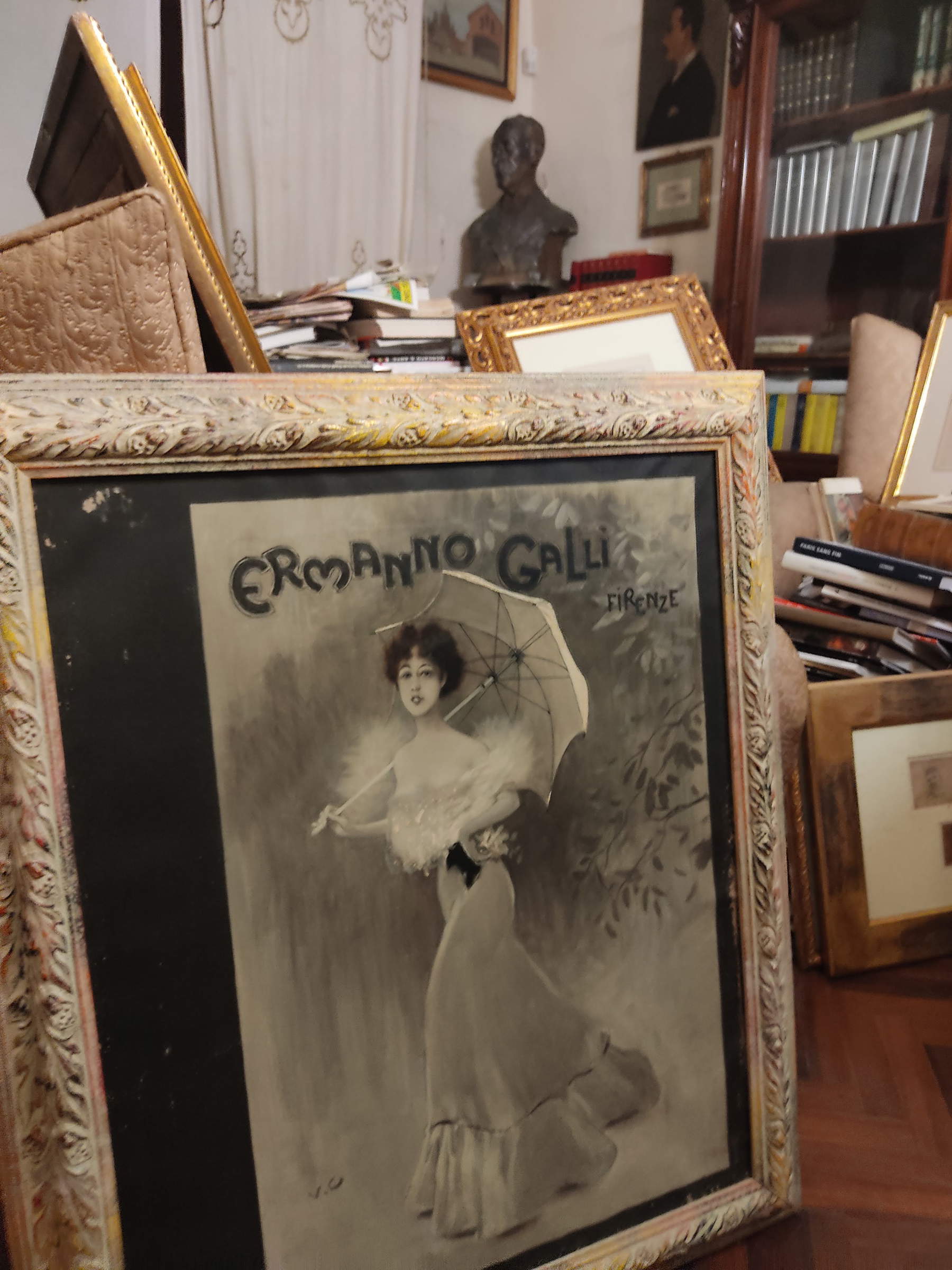

And then again documents and notebooks that belonged to the artists, an entire suitcase with all kinds of testimonies by Lorenzo Viani. In this house where Pepi lived for a long time, these works are mixed with even more disorder than in the previous home, in a chaos that is complemented by countless catalogs and art books, which show how solid Pepi’s self-taught training must have been anyway. In addition to these, of course, there are also important oils, those by Fattori, Cabianca and Borrani, Lega, including a splendid pastel with a woman caught reading, and even more numerous works by that multitude of artists too hastily lumped together under the name of post-Macchiaioli. Prominent among them are works by Augusto Rey, two exquisite operettas that came out of the hand of Eugenio Cecconi, the Gioli brothers, the Tommasi, a very limpid painting by Manaresi with Bathers at Quercianella, Ulvi Liegi, Renato Natali, Ruggero Panerai, Leonetto Cappiello, and Mario Puccini. In looking at the works one must be careful not to trip over a woman painted by Vittorio Corcos, not fail to see that splendid still life by Bartolena resting on the floor, and be shown where Oscar Ghiglia’s very powerful self-portrait is. Going upstairs between the bathrooms and the rooms, you will catch a glimpse of a few other gems: a Daniel Spoerri, Burri, and some lithographs and drawings with high-sounding signatures, Warhol, Picasso, Miró and others.

In this magma of colors, shapes and figures, the visitor is bewildered but Pepi like a new Virgil seems to remember every location, even if he cannot avail himself of any complete catalog.

“An entirely occasional supply and, in our opinion, made with chaotic conduct, such that a culturally plausible profile of aesthetic-historical value cannot be defined”: this is how the Pepi collection is defined in an expertise signed by leading experts regarding a judicial dispute over the veracity of some works.

An understandable, but summary and partial judgment, made following examination but without soul. A play on words, to say that facing Pepi’s collection, grasping its meaning, the choices and motives that animated and formed it, sharing its arrangement and organization is not immediate, nor plausible if we rely on the canons we have been taught.

What Pepi has made is not a museum because it seems alive to us: it may be that calculated chaos that distances it from the aseptic taxonomic norms that dissect the artistic fact, like a scientific phenomenon, or because it does not impose itself as a temple with the work to be worshipped on a pedestal, but as a home, where the work becomes familiar, something one can surround oneself with, fill one’s life with without reverence or devotion. Far from mystical auras and market values, the works become testimonies, pieces that impose themselves on the visitor with serendipity, who will structure his or her visit, perhaps ignoring something important, but will glimpse or rather discover something new, without the imposition of having to dwell or get excited in front of some work, whose celebrated signature we have been taught works as a mark of quality.

Pepi, far from glossy circles, in spite of established canons and clichés, eschewing power games, has always tried to make art an accessible thing, available to the many and not just for the benefit of the few. He never refused to collaborate with or make available part of his collection (check also the endless list of exhibitions and catalogs) even for exhibitions that were not of great echo but of sure value, aimed at enhancing the many artists in the collection even in the provincial towns where they were born or had worked. He had even proposed to the City of Livorno to exhibit a good part of his collection in the Giovanni Fattori Civic Museum on a long-term basis, a project that was later frozen.

But so tenaciously have his work and expertise often been questioned that even he sometimes with some bitterness wonders if this is really the case, if he has not done something wrong. Yet in spite of the academic titles, the successes achieved in his battles against forgers, the realization of a collection composed of works and testimonies of artists that only in recent if not very recent times are acquiring the proper consideration, and that have been saved from dispersion, the support of the artists themselves, the willingness to make his collection as accessible as possible without any economic purpose (one does not pay to visit the Pepi collection), might also seem sufficient to better define and consider the figure of Pepi.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.