“The valley was dominated by a feeling of emptiness, of vertigo, disappeared the magic that emanated from above. It seemed to you that they had kidnapped the two guardians, beneficent, who from their position guaranteed a balance. The two Buddhas who had protected the view for centuries had been erased, you looked at the two empty caverns with anguish.” The words to describe the sense of disquiet left by the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan are those of the great photographer Steve McCurry, collected in Gianni Riotta’s book Steve McCurry’s World. The U.S. photographer’s reportage has repeatedly documented what was happening in the Asian country, which has been torn apart by decades of wars that have devastated even its artistic heritage: the loss of the two rock giants is the most internationally known.

For the world, the destruction of the two Buddhas represented one of the most significant cultural losses since World War II, even considering the fact that it was a deliberate act. And to give an idea of the importance of these two monuments, McCurry uses an effective image: “Imagine going back to France and seeing razed to the ground the Gothic cathedral of Notre-Dame de Chartres, which they began building in 1194, when the Buddhas were already centuries old. You arrive from the highway, the cathedral towers in the distance, solemn, magnificent. It is gigantic, towering over the surrounding area, and you wonder what it must have looked like half a millennium ago, surrounded only by huts and villages. Wayfarers, peasants, merchants glimpsed it from afar, used its spires to orient themselves, they must have been captivated by it, the cathedral was a source of inspiration for all. The same charismatic function performed by the Buddhas, their destruction shocks, as if a negative cycle shakes our time.”

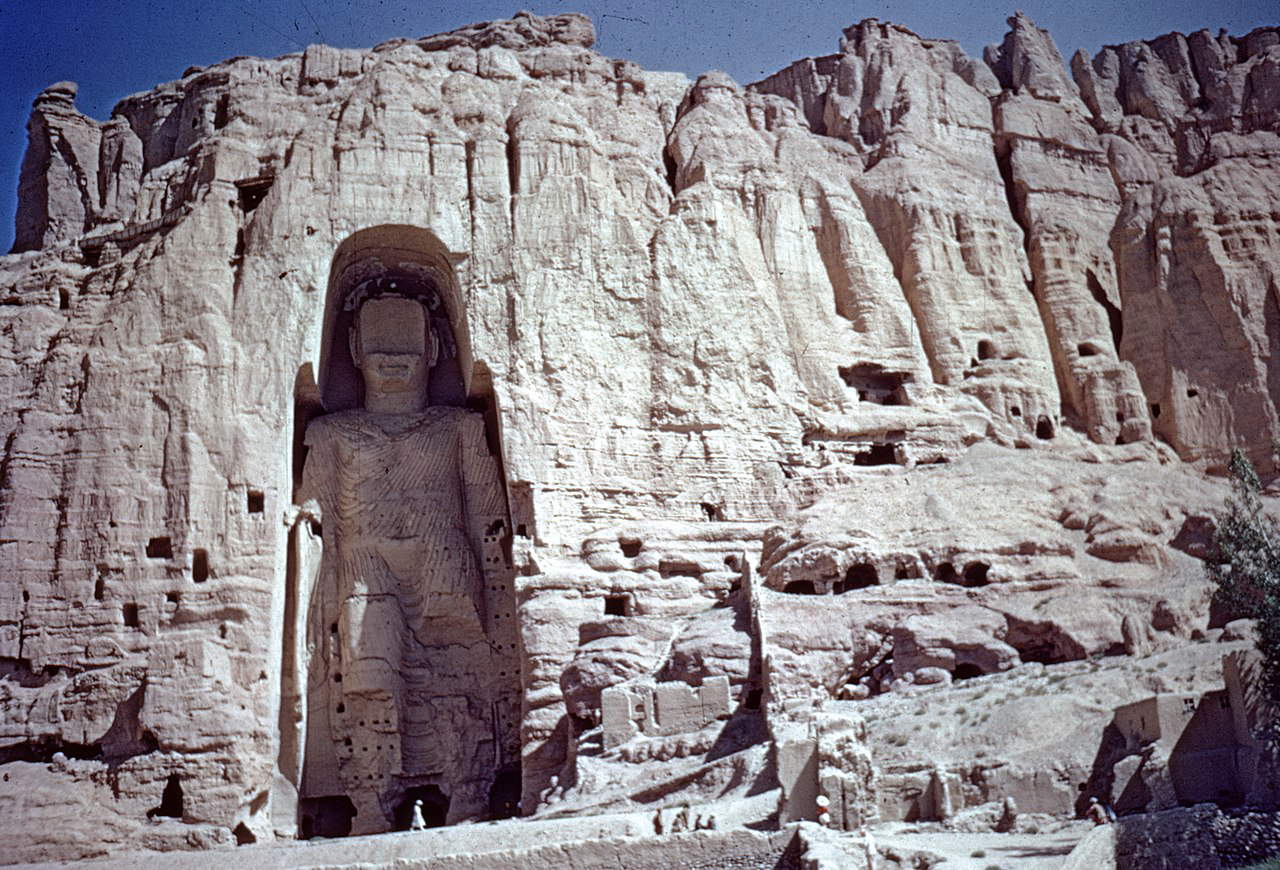

|

| The Buddha of greater Bamiyan. Photo by Françoise Foliot |

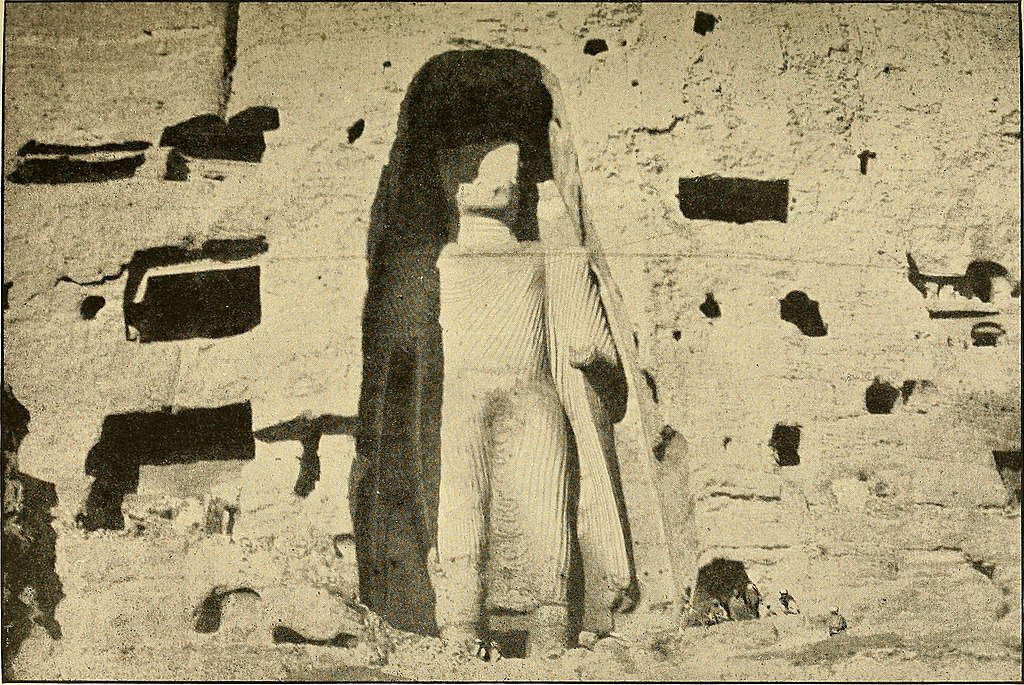

|

| The Buddha of Bamiyan minor. Photo by John Alfred Gray, 1895 |

March 2, 2001: Around the Bamiyan Buddhas, two monumental Buddha statues from the 6th-7th centuries A.D., carved into the rock of Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Valley, the Taliban, which came to power in the country during the civil war, placed massive amounts of dynamite. Until 1998, the area in which the Buddhas stood was under the control of the militias of Hezbe Wahdat, the Islamic Party of Afghanistan, one of the factions that were part of the Northern Alliance, or the coalition that, during the civil war, fought against the Taliban’s Islamic emirate. By August of that year, the Taliban had defeated their opponents in the battle of Mazar-i Sharif, securing control of the latter city, the fourth largest in the country and the capital of Balkh province, and the entire surrounding area. Already during the battle some Taliban leaders, fundamentalist followers of an iconoclastic Islam, had indicated their intention to blow up the Buddhas of Bamiyan, and operations had already begun to place TNT around the monuments.

It had taken the intervention of Mullah Omar to stop, at least for the time being, the destruction: the Taliban’s supreme leader had issued a decree in July 1999 to preserve the Buddhas, in which it could be read that despite the fact that there were no longer any Buddhists in Afghanistan, “the government considers the Bamiyan statues to be an example of a source of revenue for international visitors to Afghanistan. The Taliban declare that the Bamiyan statues should be not destroyed but protected.” The intention, however, will be very short-lived: not even a couple of years later, on Feb. 27, 2001, the Taliban officially declare that the statues will be destroyed, and international mobilization is to no avail: the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the body that currently represents 56 states (then 54) with the aim of protecting the interests of Muslim populations around the world, also moves. All OIC member countries are joining the protests of those calling for the Buddhas to be saved. Pakistan’s President Pervez Musharraf sends a delegation to negotiate with Mullah Omar to avert the destruction of the monuments. Journalist Steve Coll, in his book Ghost Wars, reported what Pakistani Interior Minister Minuddin Haider had said during the talks: that the Quran states that Muslims should not destroy the gods of other religions, that those statues are older than Islam itself, that thousands of Muslims of all ages had been to Afghanistan without ever having thought of destroying them. “Are you then Muslims different from them?” Haider allegedly asked the Taliban. However, Mullah Omar’s answer, according to Coll, is puzzling: “maybe they did not have the technology to destroy them.” Agence France Press reports of a conversation between then-U.N. Secretary Kofi Annan and the Taliban government’s foreign minister, Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil, during which Annan reportedly pointed out to Muttawakil the position of the other Islamic countries, all of which were against the destruction of the statues, adding that such an operation would draw away from Afghanistan the support of the international community during the humanitarian crisis the country is still going through after so many years of civil war. According to the deposed king of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah, the destruction goes “against the national and historical interests of the Afghan people.”India, even, offers to relocate the Buddhas on its national territory.

There is nothing to be done, however: the statues’ fate is sealed. And on March 2, dynamite begins to explode. Artillery fire is added to the explosives: bringing down two huge statues, 38 and 53 meters high, carved into the rock and then attached to the mountain, is not easy even for the most furious iconoclasts. Anti-tank mines are also planted, rockets are fired at the statues. Within a couple of weeks, the statues are destroyed, and all that remains of them are the outlines in the rock, now reduced to two shadows, but still recognizable nonetheless: the Taliban madness has not succeeded in completely wiping out what has stood in the mountains of the Bamiyan Valley for 1,500 years. And it has, however, sparked outrage around the world and among all religious communities, including Islamic ones.

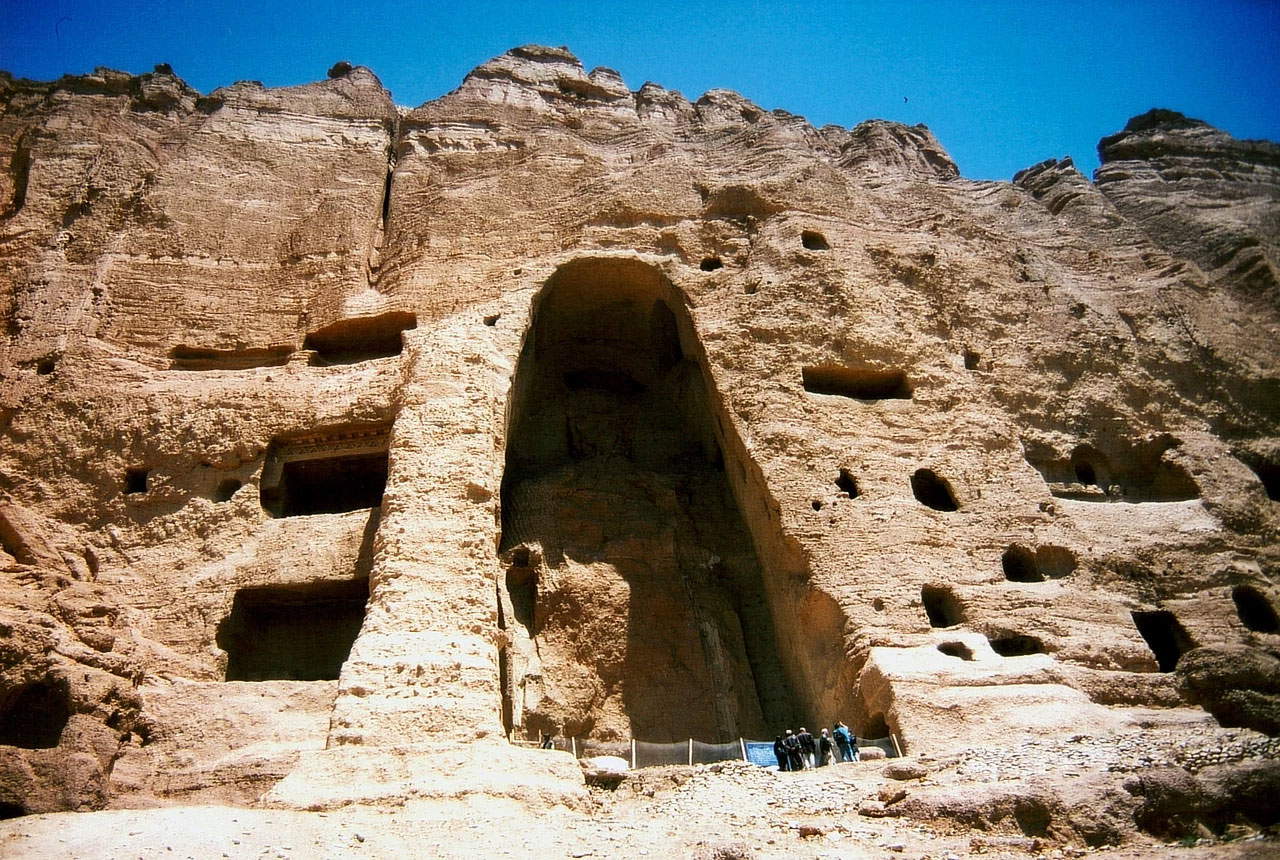

|

| The Bamiyan valley with the large statue before 2001. Photo by Françoise Foliot |

|

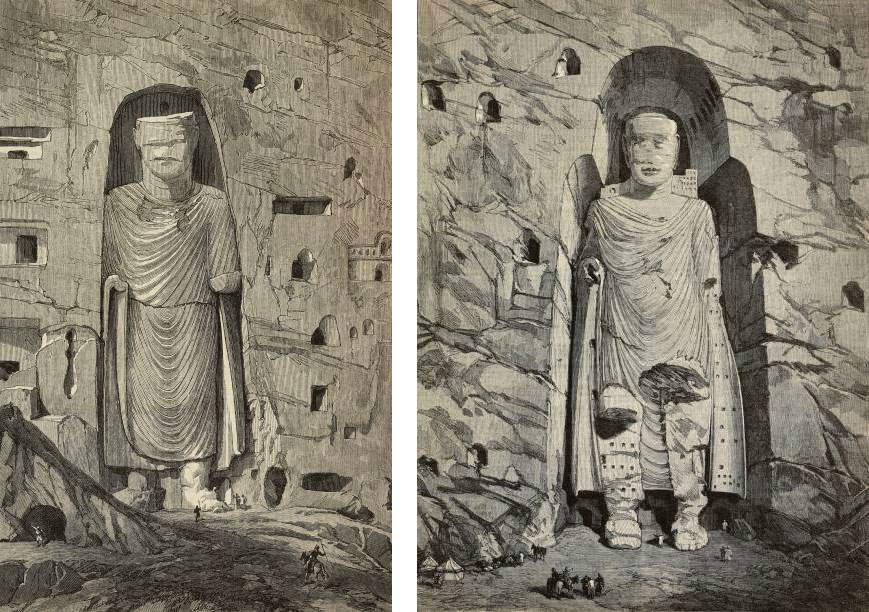

| The two Buddhas in an engraving by Alexander Burnes published in 1833 |

|

| The two Buddhas in an illustration by P.J. Maitland published in The Illustrated London News magazine (1886) |

Prior to their destruction, the Bamiyan Buddhas were among the world’s most impressive monuments and the largest extant examples of standing Buddha statues carved from rock (there is a larger one, the Giant Buddha of Leshan, which is located in China and is 71 meters tall, but is in a seated position). These were, as mentioned above, two colossal Buddha statues, one 38 and the other 53 meters high: however, we do not know who commissioned them, nor to whom the design is owed. They were, however, an important testimony to the presence of Buddhists in Afghanistan in ancient times. Indeed, the Bamiyan Valley lies on the road from India to Central Asia, thus configuring itself as a location near the Silk Road, the complex of trade routes that connected the Far East to Europe, with branches that also passed through the Indian subcontinent. The city of Bamiyan, which today has a population of about sixty thousand, located about 250 kilometers from today’s capital Kabul, was in ancient times a junction along the trade routes as it stood in the middle of a fertile plain lying around the banks of the river of the same name: it was therefore a frequent destination for merchants but also for Buddhist missionaries, who were long active in the area. A number of Buddhist monasteries stood around Bamiyan in ancient times, and the city itself, until the time of the first incursions of conquerors of the Islamic faith, was an important Buddhist philosophical and artistic center (the Buddhist religion, before the Islamic conquest of Afghanistan, which was completed in the 10th century, was the prevailing religion in the territory).

The statues, writes scholar Llewelyn Morgan, “were carved in high relief, attached to the wall of their niche from the height of the hem of their robes to the back of their heads, in an arrangement that facilitated the important Buddhist ritual of circumambulation: worshippers could walk around the statues either at ground level, behind their large feet, or on top of their heads.” (Originally it is thought that there was a ramp or pathway next to the larger Buddha to reach the top, which has since disappeared over time due to erosion that has always plagued the very friable conglomerate rock of which the mountain from which the two monuments were carved). The statues thus had ritual purposes: they were worshipped by Buddhists in a practice typical of Eastern religions of walking around an image or relic of the deity. According to art historian Susan Huntington, the two statues represent two manifestations of the Buddha: the larger one is the Buddha Vairochana, or the representation of the celestial Buddha, while the smaller one is the Buddha Shakyamuni, another name by which Gautama Siddhartha is known, i.e., the historical Buddha, the monk who lived between 566 B.C. and 486 B.C. and was the founder of the religion.

The statues were carved out of a rock that, as mentioned, is very delicate and therefore did not lend itself to very elaborate decoration: the two Buddhas were therefore roughly hewn, although the folds of the draperies of the samghati, the robe, were traced directly onto the rock. Clay linings were used for the more minute decorations: there are holes in the stone that housed wooden stakes to which the clay linings were applied, although by the 20th century the vast majority of these decorations had already been lost (by the date of destruction by the Taliban, however, it was still possible to see some traces of them). The two Buddhas are dressed in the traditional manner of Buddhist monks, with the typical attire known as tricivara and consisting of three garments: an uttarasanga, or robe for the upper part of the body; an antarvasaka, for the lower part; and the samghati, the robe that covered the shoulders and reached almost to the feet. The folds of the samghati were made with great precision, described to suggest the idea that the robe adhered to the body (and thus the anatomy of the figures could be perceived). The forearms of both statues (except for the left forearm of the elder Buddha) were projecting, as they were designed to move forward (the hands, however, were lost before the 20th century: already in 19th-century engravings the statues appeared stumped). The most striking physical peculiarity of the two Buddhas, however, was the absence of faces: again, as early as the 19th century two vertical walls of rock could be seen instead of faces. It is unclear whether they were removed by Muslim iconoclasts in ancient times or whether the two Buddhas were conceived without the facial features for practical reasons: however, Morgan reports that scholars are leaning toward the second hypothesis (“a groove between the horizontal and vertical planes on the face of each of the two Buddhas,” Morgan writes, “has been interpreted as an anchor point for wooden structures-i.e., masks in their own right-that represented their features.”). Looking at the elder Buddha one could see theusnisa, the protuberance on the top of the skull symbolizing his transcendent intelligence, and both statues had parts of their pendulous ears, as well as traces of their hair.

The time when the two Bamiyan Buddhas were executed is not known with certainty. For a number of indications (the style, radiocarbon dates, the period of greatest prosperity of the city of Bamiyan) their execution is thought to be between the mid-6th and early 7th centuries. The style is that ofGandhara art, also known as Greco-Buddhist art, a syncretic art form between the artistic expressions of ancient Greece and those of Buddhism: it flourished in northwestern India in the first centuries A.D. and is named after the Gandhara region where it appeared. It was an area that constituted a true bridge between East and West: in the first century AD, in fact, this territory, at the time occupied by the Kusana Empire (which stretched over an area where today North India and parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan are broadly located), was subject to widespread and entrenched Buddhist missionary activities, but it also maintained contact with the Roman Empire. The fusion of these two cultures gave rise to Greco-Buddhist art within which the Bamiyan Buddhas should also be counted.

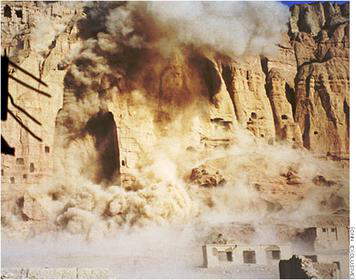

|

| Destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan |

|

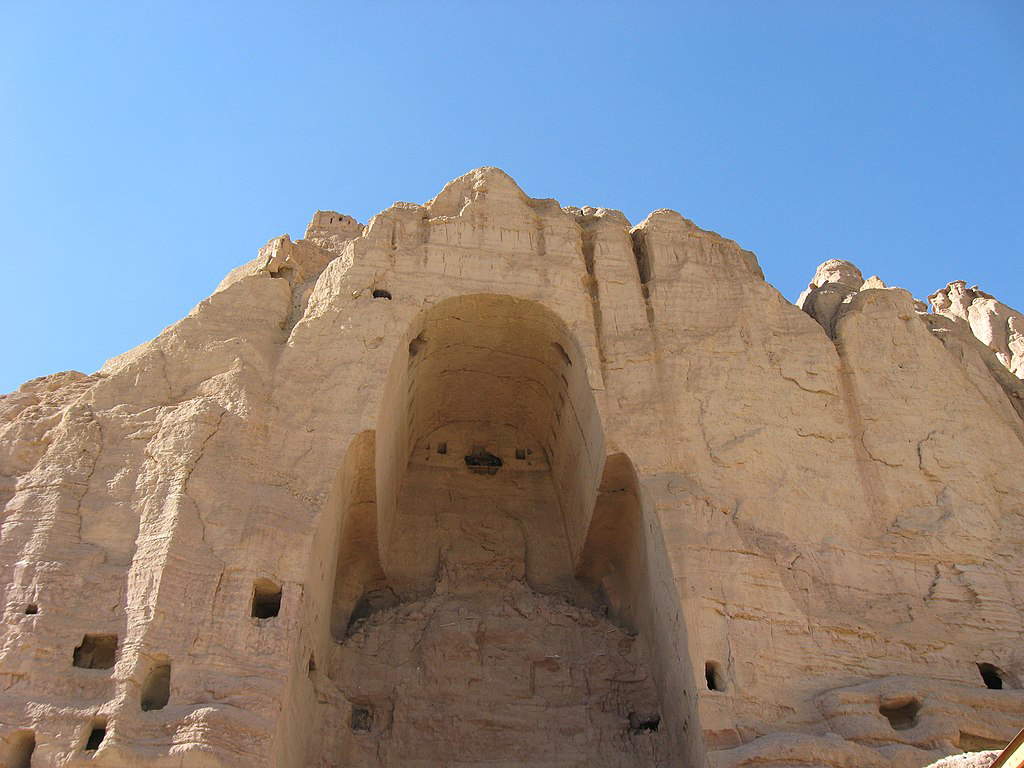

| The niche of the elder Buddha after destruction. Photo by Tracy Hunter |

|

| The niche of the Greater Buddha after destruction. Photo by Tracy Hunter |

|

| The niche of the lesser Buddha after destruction. Photo by Alessandro Balsamo |

|

| Bamiyan Valley with the town and, in the background, the empty Greater Buddha niche. Photo by Roland Lin |

Officially, the decision to destroy the Buddhas (which had survived the early Islamic conquerors, the arrival of Genghis Khan’s armies, and the 1979-1989 war in Afghanistan, the one that pitted the forces of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, supported by the Soviet Union, against the Sunni Mujahideen supported instead by the United States and other Western countries) was made for religious reasons. According to the fundamentalist interpretation of Islam practiced by the Taliban, the religion prohibits the depiction of the human figure and does not allow idols of other religions. “Muslims,” Mullah Omar is reported to have said at the time of the destruction based on the March 6, 2001, Times report, “should be proud of destroying idols. Praise be to Allah for destroying them.” In an interview with the Japanese daily Manichi Shimbun, the then foreign minister of the Taliban government Muttawakil said, “We are destroying the statues in accordance with Islamic law and it is a purely religious matter.”

However, such statements jarred with Mullah Omar’s decree issued just a year and a half earlier, in which the desire to protect the Bamiyan Buddhas was affirmed. What had changed then in the meantime, given the fact that the Taliban’s interpretation of Islam had not experienced significant changes? It is definitely more likely that the reasons for the destruction were related to the international political situation. An article published on March 18, 2001, in the New York Times, signed by Barbara Crossette, reports that the Taliban ordered the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas after a visit by an international delegation consisting of European envoys and a UNESCO delegate: according to the piece, the delegation allegedly offered economic resources to the Taliban to protect the Bamiyan Buddhas. The Taliban were reportedly outraged by the Western offer, since the fundamentalist government would have preferred money to feed the population, and decided to destroy the statues out of resentment. This version was provided to the reporter by Sayed Rahmatullah Hashimi, a Taliban ambassador who allegedly participated in the talks: “When your children die in front of you,” Rahmatullah declared, “you don’t care about the works of art.” In fact, the Western delegation could only offer resources earmarked for the protection of the two statues, according to the New York Times. “If you destroy our future with economic sanctions,” Rahmatullah later added, “it means you don’t care much about our cultural heritage. We could have destroyed the statues three years ago,” Rahmatullah later added. “Why didn’t we do that? In our religion, if something does no harm, we leave it alone. But if the money goes to the statues while our children there by the side are starving, then that makes them harmful, so we destroy them.”

Yet even in the face of such an explanation, the reasons may be deeper. Anthropologist Pierre Centlivres, in one of his scholarly articles in 2008, lists other possible reasons, in addition to the explanation that relies on the Taliban’s wrath over the economic bid for the statues at a time of severe humanitarian crisis. The first is related to the sanctions the UN imposed on Afghanistan in December 2000: the destruction may thus have been a Taliban reaction to the international community’s measures. The second is the failure of the international community to react following the measures by which Mullah Omar banned opium cultivation in Afghanistan (it was the country’s most flourishing economic activity). The third reason is another reprisal against the United Nations for letting former President Burhanuddin Rabbani, rather than a member of the Taliban, hold the seat of Afghanistan’s delegate, despite the fact that the Taliban controlled 90 percent of the country at the time. According to Centlivres, it is therefore more likely that it was a combination of all these factors that caused the Taliban to ripen the idea of destroying the Bamiyan Buddhas, rather than religious motives, despite official versions passing off the demolition of the two monuments as an internal religious issue. “Unspoken factors and reasons,” Centlivres wrote, “carry more weight for observers than official motives. Contextual factors seem to be more plausible than theological arguments.”

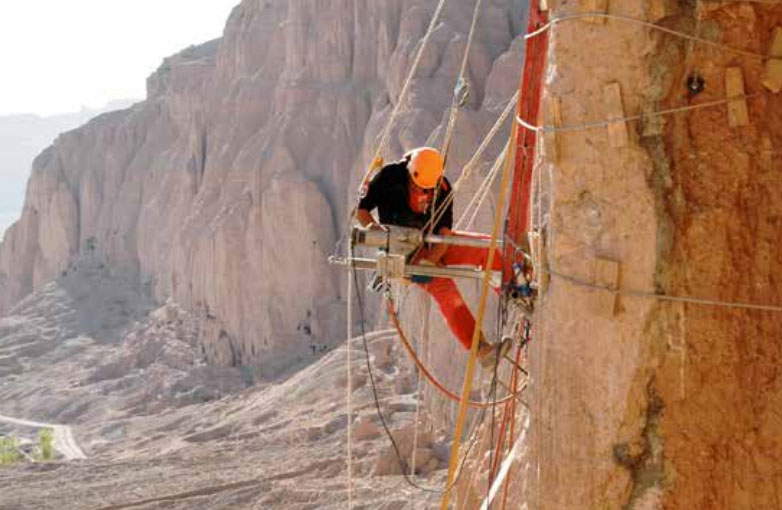

|

| Trevi S.p.A. worker at the site of the Bamiyan Buddhas (2003-2006) |

|

| Jason Hu and Liyan Yu’s hologram |

|

| Wall paintings on the wall of the Greater Buddha |

Since the fall of the Taliban regime, the international community has been working to try to preserve what is left of the Bamiyan Buddhas, partly because of the fact that the rock on which they were made is extremely vulnerable and subject to rapid erosion. Since 2001, that is, since Western forces returned to Afghanistan, projects have been put in place to preserve what exists. One of these bears an Italian signature, that of the Cesena-based company Trevi S.p.A., which took on the task of consolidating the niches after a Unesco study in 2003 aimed at identifying the parts of the rock face subject to the greatest risk of collapse. “The international team of experts,” reads a company document, “worked to stabilize the remaining structure of the statues and the rock face allow the subsequent safe intervention of archaeologists and restorers. It was a long intervention on a rock already deteriorated by natural causes and severely damaged by the explosions, implemented with numerous solutions that included the installation of a monitoring system of the most open cracks, the installation of anchors, nailing and the temporary fixing of some blocks with a network of steel ropes and with metal contrast beams. Thanks to the indispensable international economic support and strong support from the Afghan authorities, this project is an important example of the application of advanced technologies in one of the world’s oldest places of art and history.”

Reconstruction projects were then advanced: the German committee of ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites), for example, suggested reconstructing the Lesser Buddha with recovered fragments and new material where what was destroyed at the hands of the Taliban was no longer available. And in 2013, an initial reconstruction of part of the base of the Lesser Buddha was developed, but it was stopped by UNESCO because it was done without the body’s approval and probably in violation of the Venice Charter, which stipulates the use of original material in the reconstruction of destroyed monuments. In 2015, two Chinese film makers, Janson Hu and Liyan Yu, “recreated” Buddhas with 3D holograms. The fall of the Taliban has since given scholars from around the world the opportunity to study the site more closely: not only the remains of the sculptures, but also the wall paintings (in this case not destroyed by the Taliban), believed to be either coeval with the Buddhas or slightly later, and considered a formidable synthesis of Indian art with Sasanian and Byzantine influences. And since traces of oil have also been found on these wall paintings, it is likely that these wall paintings include the world’s oldest known examples of oil painting, some six centuries earlier than the development of oil painting in Europe.

At the moment, however, discussion about the possible reconstruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas is still ongoing, and given the political developments in the country, with the Taliban returning to power in August 2021, it is unclear what will become of the monuments. In 2017, a meeting of experts was held under the auspices of UNESCO, and it concluded that “any recovery and reconstruction project should be based on thorough multidisciplinary research and scientific analysis to ensure understanding of the structural, material and other characteristics of the damaged heritage asset.” Also in the same report, it states that “Bamiyan heritage should be considered a place of collective identity and memory, particularly for local communities; archaeological remains cannot be separated from their natural and cultural landscape.” After destruction by the Taliban, UNESCO in 2003 listed the Buddhas of Bamiyan, along with the surrounding archaeological area, as a World Heritage Site, with the following rationale: “The cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamiyan Valley represent the artistic and religious developments that characterized ancient Bakhtria from the 1st to the 13th century, integrating various cultural influences into the Gandhara school of Buddhist art. The area contains numerous Buddhist monastic complexes and shrines, as well as fortified buildings from the Islamic period. The site also bears witness to the Taliban’s tragic destruction of the two standing Buddha statues that shook the world in March 2001.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.