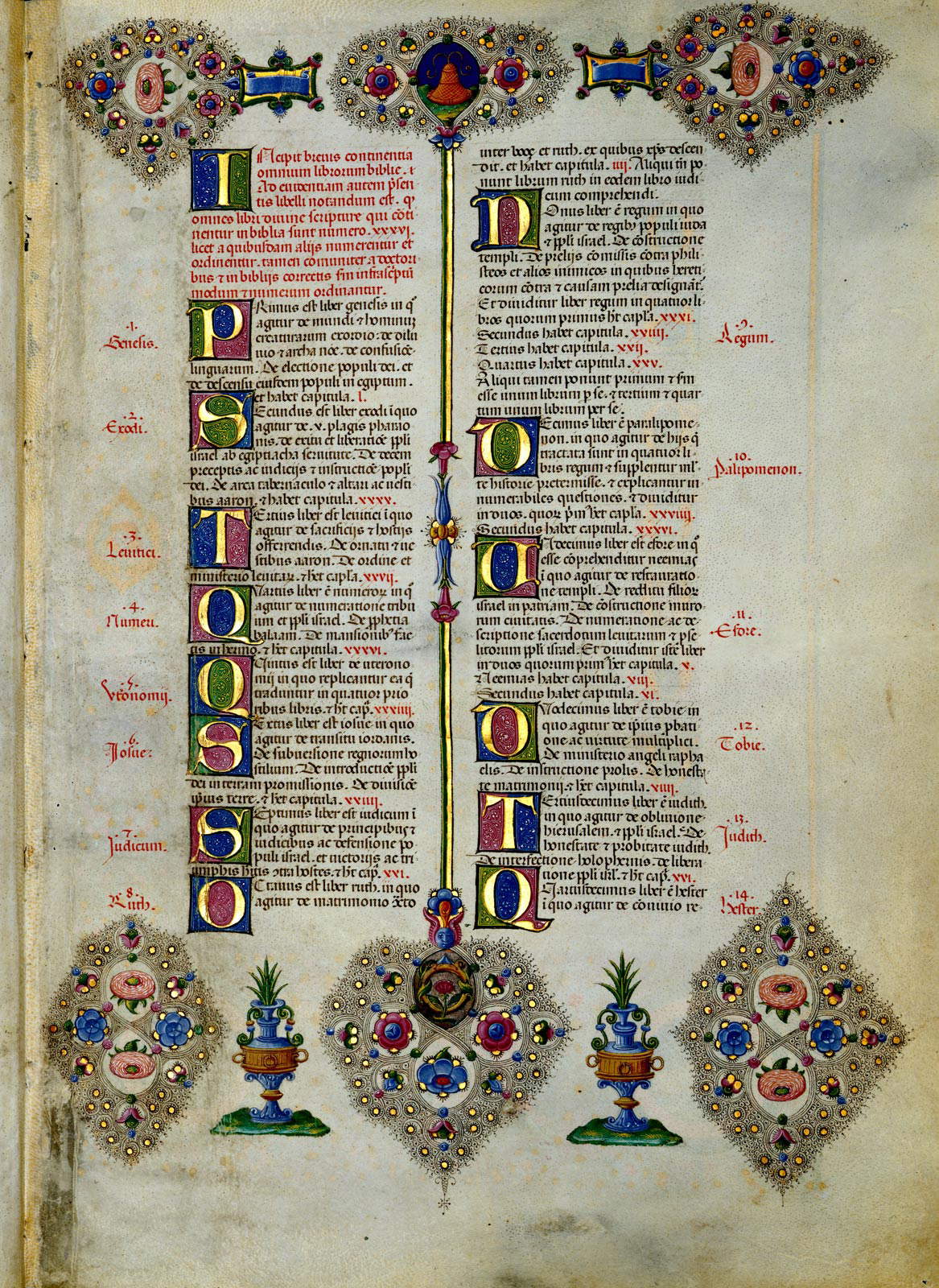

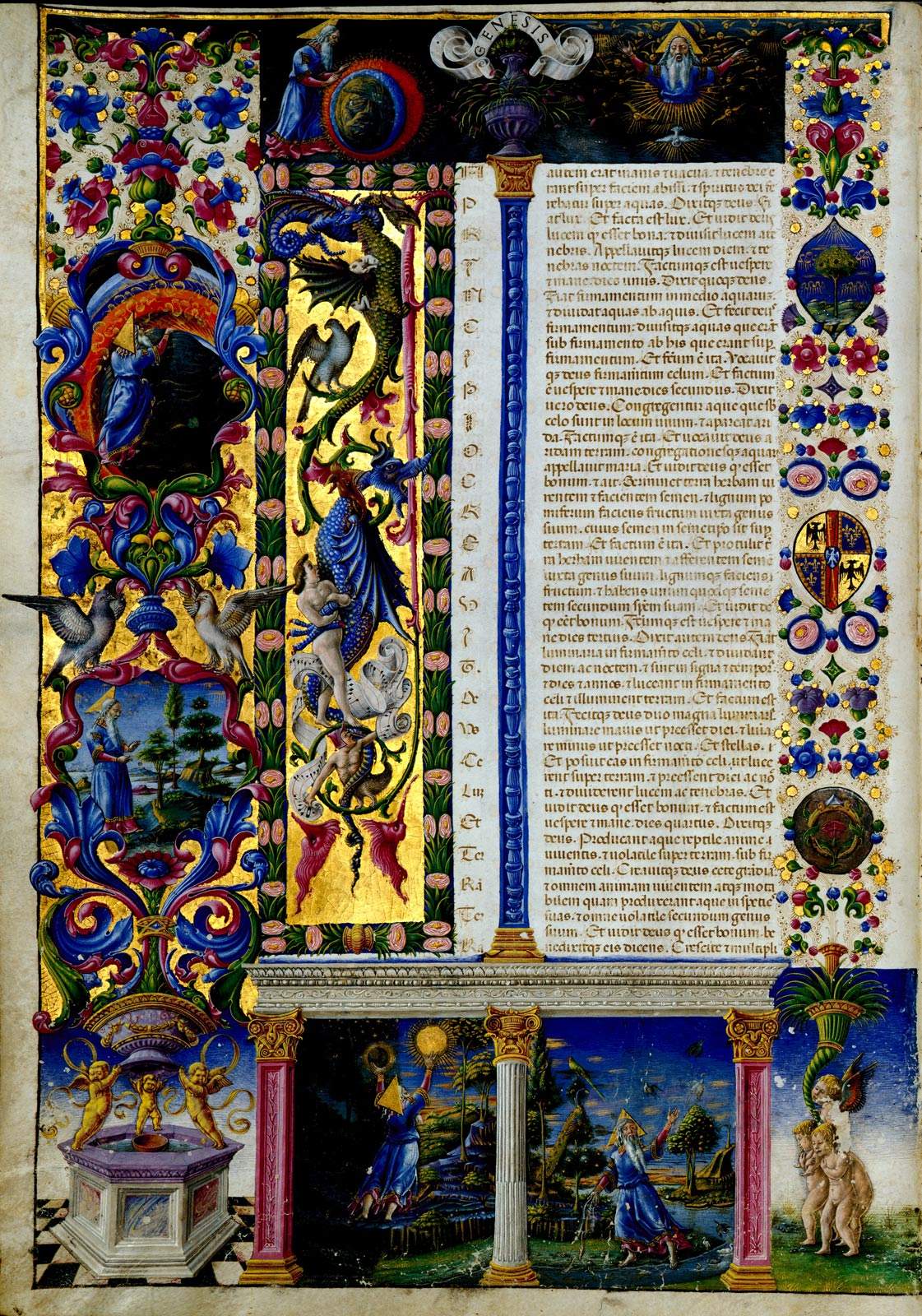

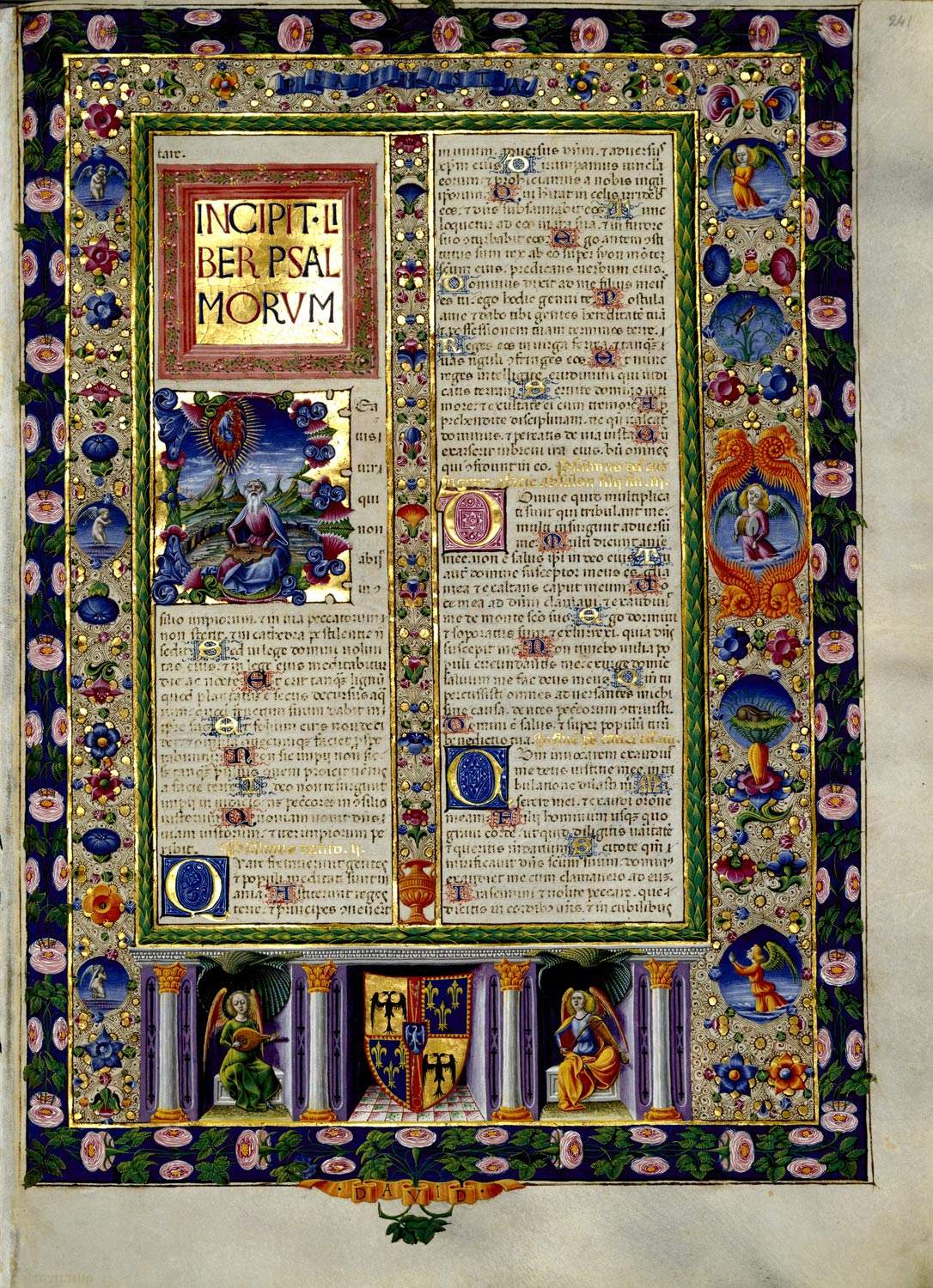

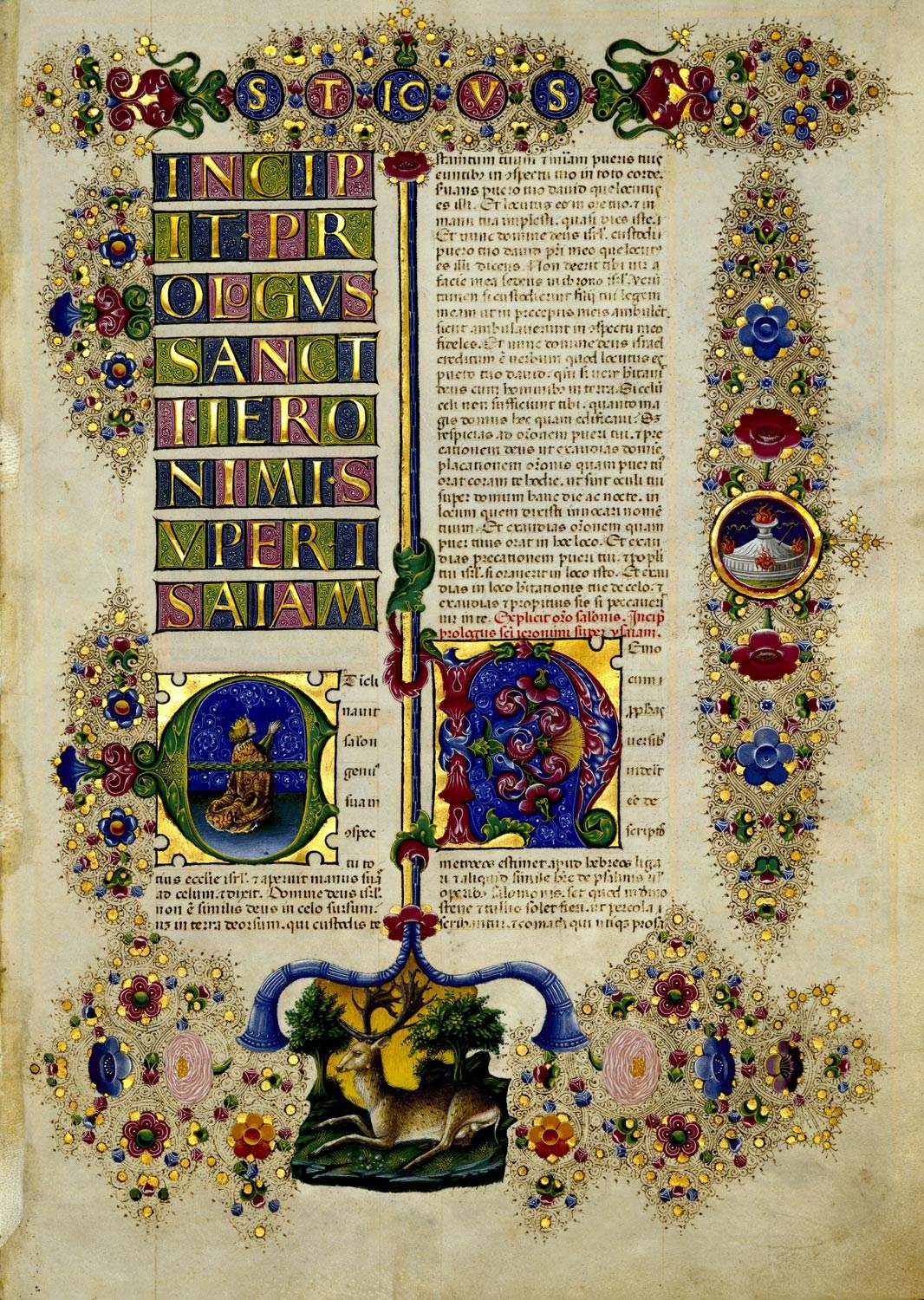

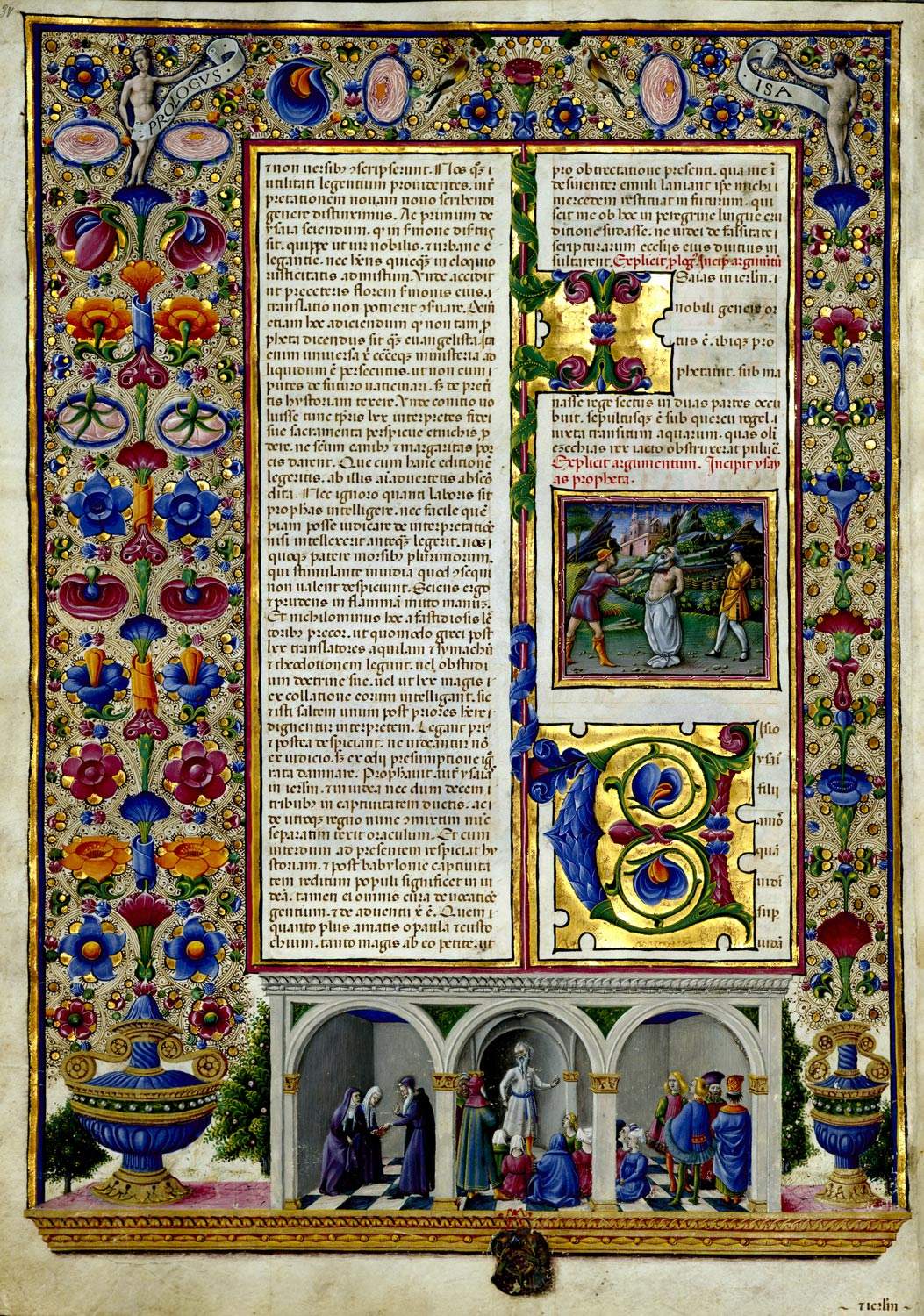

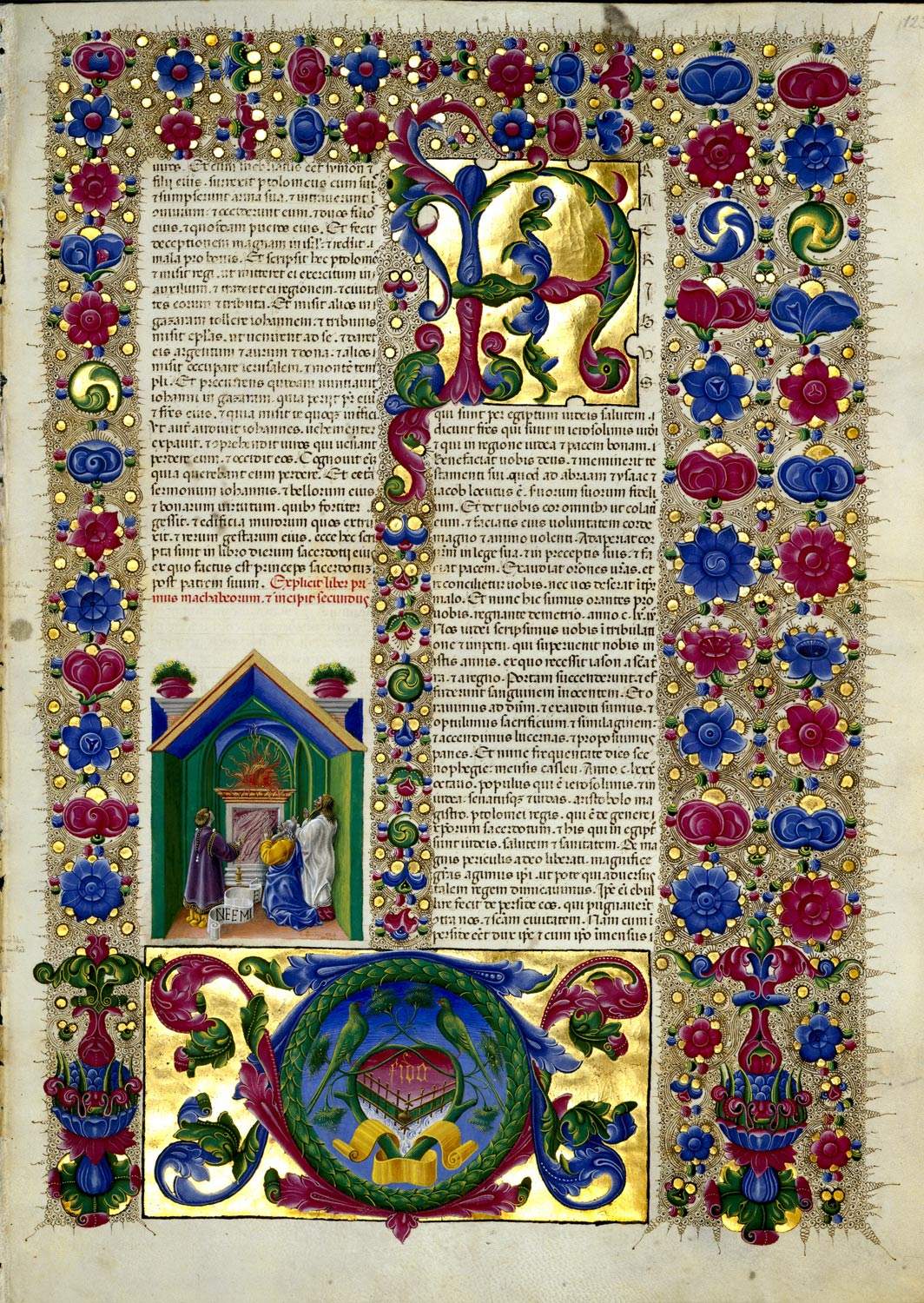

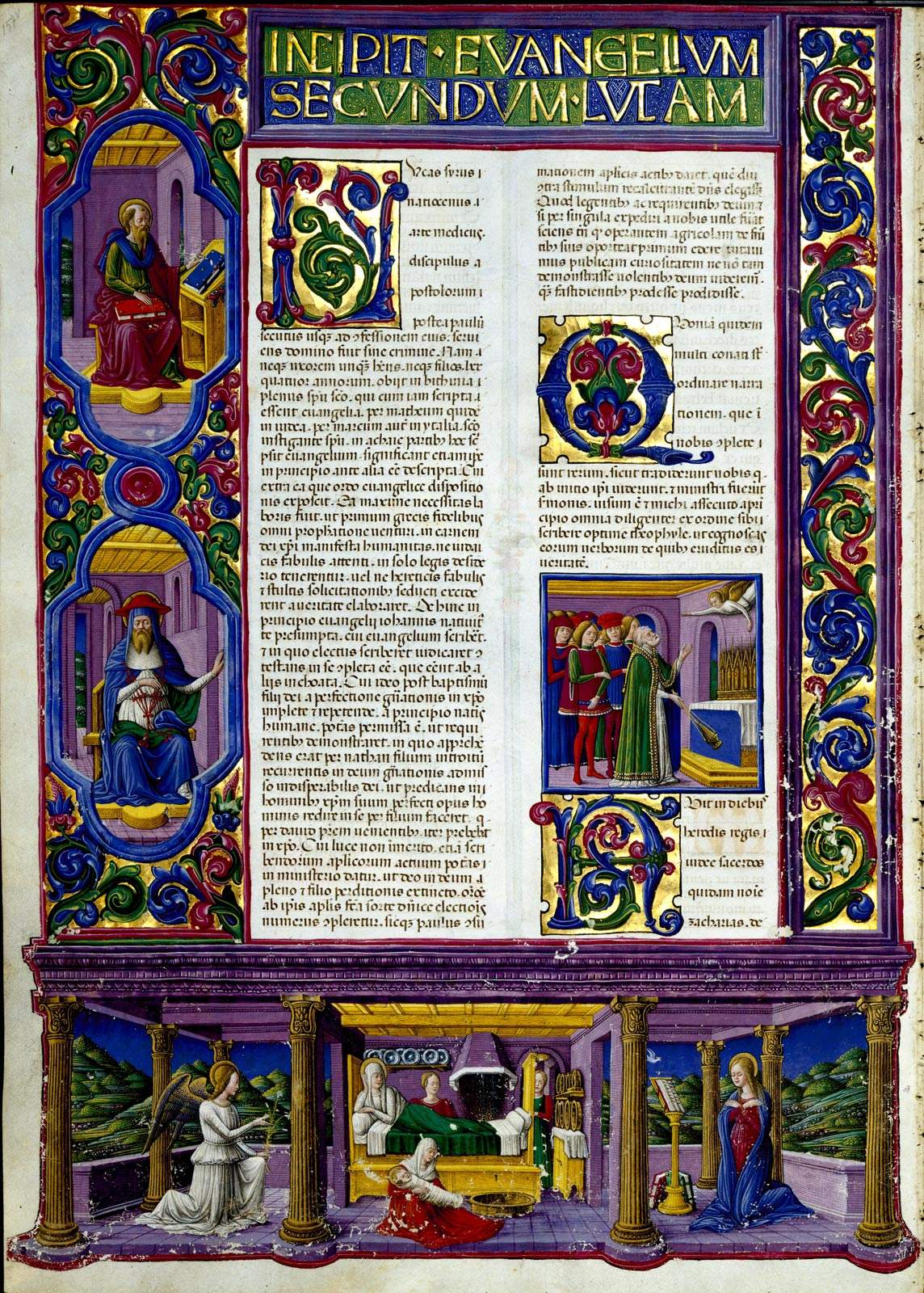

It can be said without too much hesitation that the Borso d’Este Bible, the most studied and well-known of the works preserved at the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, is the most famous illuminated codex of the Renaissance, whose fame is probably matched only by that of the Duke of Berry’s Très Riches Heures, or the Bible of Federico da Montefeltro. It is an extraordinary masterpiece on parchment that was the work of a team of illuminators led by Taddeo Crivelli (Ferrara, 1425 - Bologna, 1479), one of the greatest illuminators of the Renaissance, a pupil of Pisanello and one of the leading artists at the court of Borso d’Este (Ferrara, 1413 - 1471), and Franco dei Russi (Mantua, active between 1455 and 1482). Instead, the copyist Pietro Paolo Marone was in charge of the writing, while we owe the antique binding to the stationer Gregorio Gasperino.

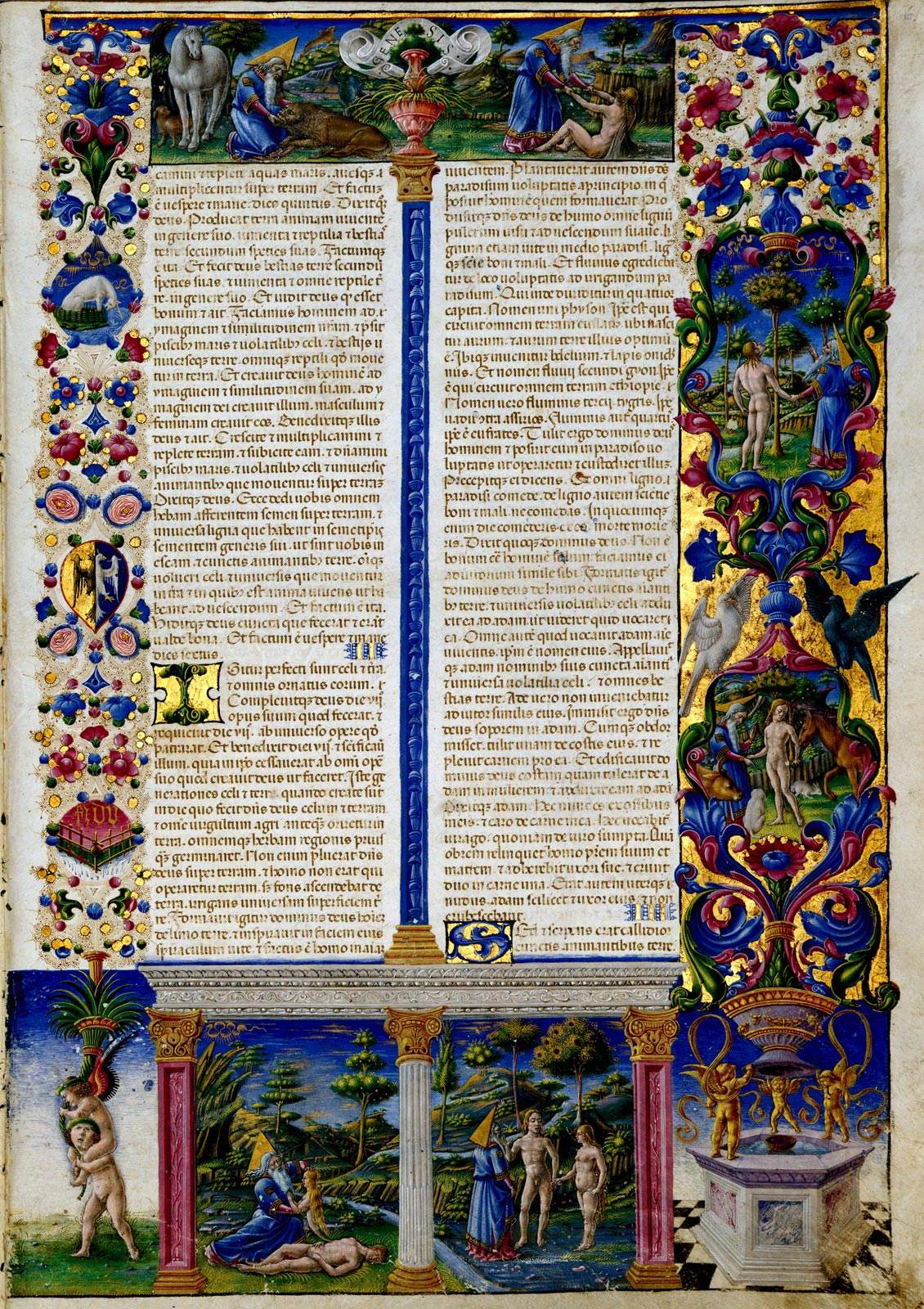

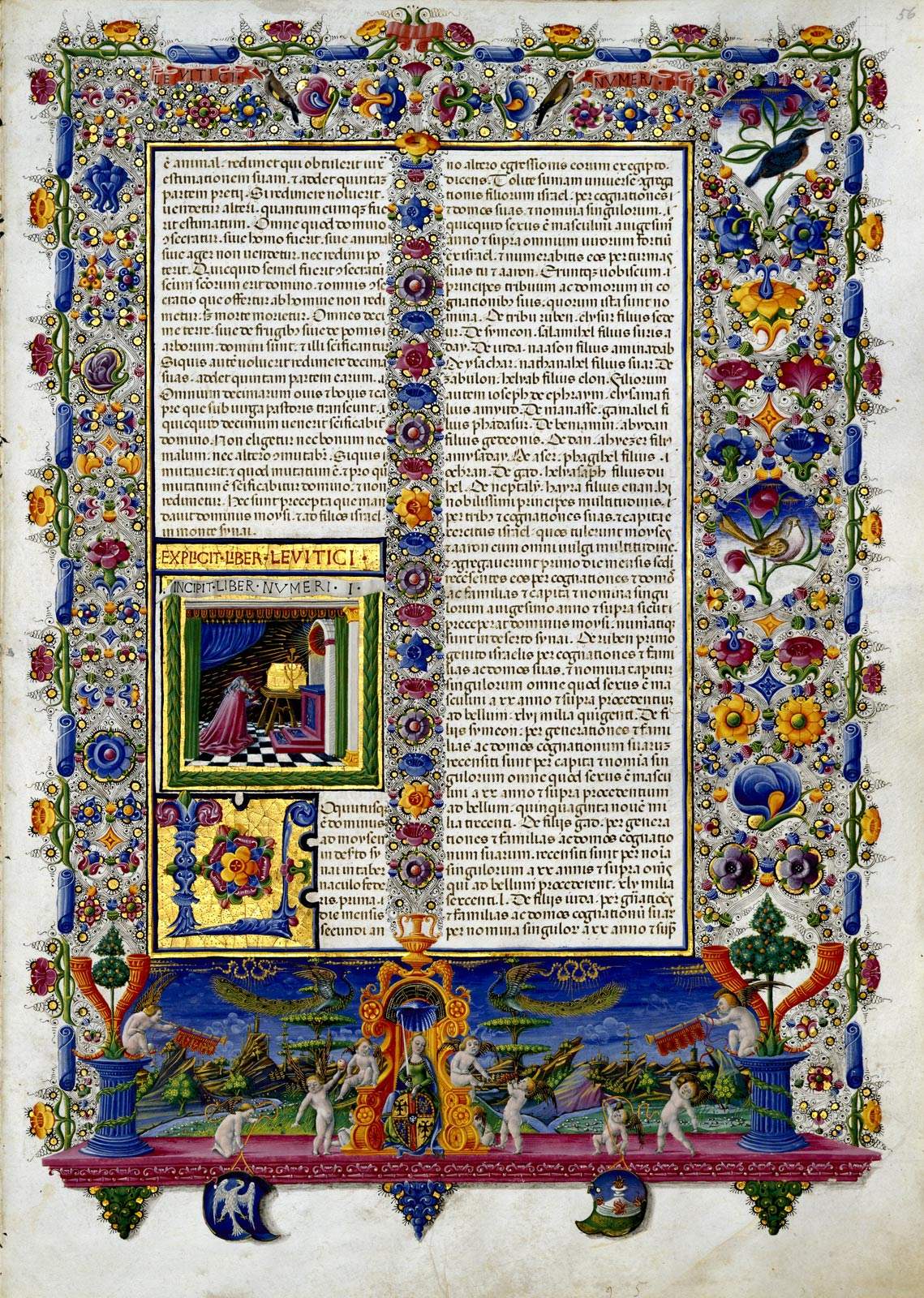

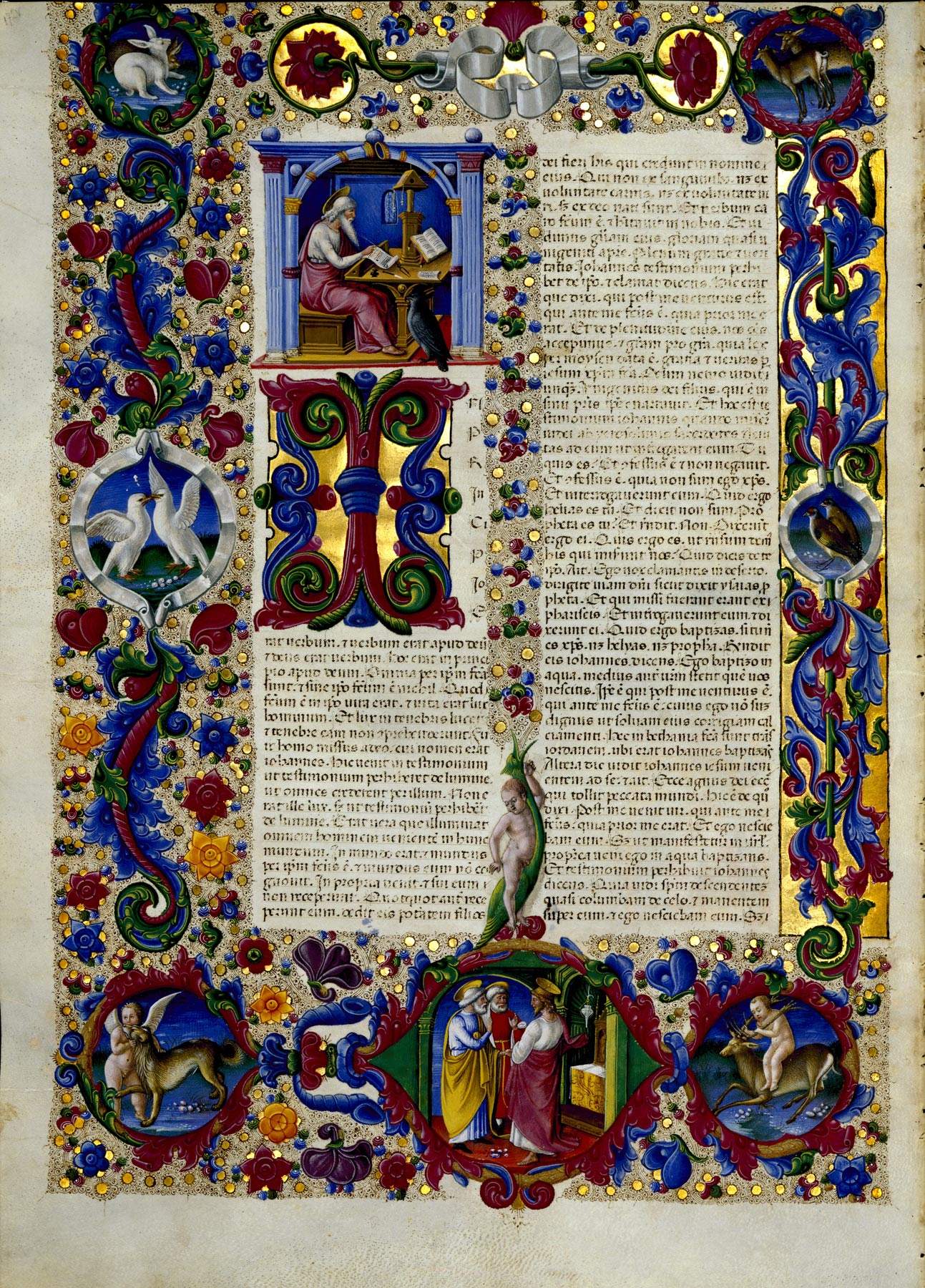

The team of the two illuminators certainly included Marco dell’Avogara and Giorgio d’Alemagna, as well as collaborators from Taddeo’s workshop. Among the collaborators, art historian Federica Toniolo, author of one of the earliest and most extensive studies of the Borso Bible in the 1990s, found from the documents the names of Giovanni da Lira, Giovanni tedesco da Mantova, Cristofolo Mainardo, Giovanni da Gaibana, Don Piero Maiante, Niccolò d’Achille, Malatesta painter and Giovanni Maria di Guiscardin de’ Sparri. To these are to be added eight other illuminators not mentioned in the payments, among whom the hands of Girolamo da Cremona and Guglielmo Giraldi have been recognized. The minor collaborators helped the two masters mainly in the preparatory stages, but some also took care of details (Malatesta, for example, was responsible for the making of some of the animals that appear in the vignettes). Duke Borso d’Este had expressly entrusted Taddeo Crivelli and Franco dei Russi with the realization of the illustrative apparatus of the precious manuscript, and apart from Giorgio d’Alemagna the other collaborators had been hired by the two responsible for the undertaking, which thus takes on the contours of an intense choral work, which moreover lasted quite some time: it took six years, in fact, from 1455 to 1461, to complete the Bible of Borso d’Este. The work consists of two large-format volumes (in-folio) with more than a thousand miniatures distributed on 604 illuminated parchment papers on both sides, for a total of 1,202 pages. The miniatures give a clear picture of the imagination and elegance of Taddeo Crivelli and his collaborators, as well as their imagination, with a style that is already modern and Renaissance but still imbued with courtly Gothic taste. The architectures, foreshortened in perspective, thus become the scene of encounters with an almost fairy-tale flavor, fights, and sacred scenes that fully express the Ferrara court’s taste for refined and elegant works, as well as the book culture that had spread in Este intellectual circles.

The Borso Bible is presented with pages inserted within refined frames decorated with plant motifs in whorls and the text arranged along two columns. In the frame, the illuminators inserted miniatures to illustrate the episodes narrated, but there are also detailed descriptions of plants and animals, as well as the Este coats of arms and emblems that always refer to exploits related to the duke and the Ferrarese state. A 2008 study took stock of precisely these latter elements of the Borso d’Este Bible, which were previously often overlooked by critics. On plants, for example, Roberta Baroni Fornasiero and Elisabetta Sgarbi found the presence of plant essences that describe episodes recounted in the biblical texts (e.g., wheat, barley, olive tree, and vine, all plants well known to people of the Renaissance and Ferrara since they also cultivated in Italy), but there are also plants that are not necessarily related to narrative needs, as well as fruits and flowers that often take on extravagant shapes, probably also of invention, and that have purely decorative purposes, to create colorful festoons around the frames within which the text is arranged.

As for the animals, the bestiary of the Borso d’Este Bible has been carefully studied by Ivano Ansaloni, Mirko Iotti and Marisa Mari, who have also come up with a census of the quantity of animals that pop up between the pages of the manuscript: there are in particular 1.450 real animals, that is, existing in nature (in the Borso Bible there are in fact also fantastic animals), including 91 invertebrates (in the totality insects) and 1,363 vertebrates, with mammals representing the most numerous group (791, more than 50 percent of the total), followed by birds (563, 39 percent), while few are the fish and reptiles that do not come to count twenty specimens. These are animals that, as in the case of plants, are included for illustrative purposes, but often simply respond to the need to offer Duke Borso, who was a great lover of nature and hunting, the animals that might appeal to him: hence the abundance of animals typical of the marshes and woods of Ferrara, in addition to those that were hunted. Many animals are characterized by a high degree of realism, a sign that the artists had firsthand knowledge of the animals they depicted. There is, of course, no shortage of exotic species, which the artists could see in the court’s menageries, or could simply reproduce based on drawings by those who had seen them from life. Among the emblems, one of the most interesting expressions of the courtly taste of the time, when decorations, not only in illuminated manuscripts but also in paintings and especially in the halls of official residences, included symbols that alluded to qualities of sovereigns or political events, that of the paraduro, a fence with an elongated gourd (known as a “viulina”), a symbol of the rising water level and thus, by reference, of the Este reclamation, stands out.

Borso d’Este’s Bible was one of the most expensive undertakings of its time: the duke’s final expenditure was 5,609 Marchesan lire, a sum that, scholar Anna Melograni pointed out, was “extraordinary and difficult to compare with that of other codices.” To give a term of comparison, suffice it to say that in 1469, when Borso entrusted the great Cosmè Tura (Ferrara, 1433 - 1495) with the task of decorating the chapel of Belriguardo castle, in addition to the expenses for colors and materials, the duke granted the painter a monthly payment of 15 Marchesan liras, plus food for him and two apprentices. Or one can take as a reference the sum offered to the copyist, the Milanese Pietro Paolo Marone, for the entire writing of the Bible: 360 Marchesan liras. The vast majority of the expense was due to the richness of the decorations, on which almost 88 percent of the total had to be spent (the miniatures, executed with an abundance of gold and precious pigments, required 4,924 liras, while 69 were used to buy the parchment, 138 for the sewing and gilding of the fascicles, 6 liras for the wooden case that was to contain the Bible, 14 for the cloth overcover, and 97 for the silver clasps).

Such an undertaking was obviously not intended for the mere production of a book for the duke to consult in private: if anything, Borso’s Bible must be seen as an essay and demonstration of his magnificence. “Sparing no expense,” Anna Melograni explains, “Borso had conceived and commissioned an artistic masterpiece that, fitting perfectly into Pontano’s definition, allowed him, through an apparent gesture of devotion to the pontiff, to actually celebrate the affirmation of his power and the birth of the duchy of Ferrara.” Indeed, it emerges from the contracts made in July 1455 that the duke intended to have a luxury book created. However, scholar Charles M. Rosenberg has pointed out that it was rather strange to give a display of magnificence through an illuminated codex, i.e., an object that was usually intended for a private dimension: in the 15th century, examples of demonstrations of splendor that had to do with books were, if anything, about the creation of sumptuous and rich libraries, or patronage toward the literati. However, manuscripts were conceived as objects to be sent as gifts, a practice that was also regularly enacted by Borso (one can cite, for example, the gift of Giovanni Bianchini’s Astronomical Tables to Emperor Frederick III). The action of demonstrating the prince’s magnificence, according to Rosenberg, could therefore operate on two levels: the first level was that of “public actions designed to publicize his splendor and generosity to the widest possible public,” and was expressed by great architectural undertakings, commissions for the decoration of churches or palaces, large handouts to ecclesiastical bodies, or festivals and shows for the population. However, there was also a second level of actions “much more subtle and calculated to impress a more sophisticated and limited audience through the sovereign’s taste and refinement.” A magnificent private chapel, an ornate study, or, as in the case of the Bible, the commissioning of a scholarly text or richly decorated manuscript could have served this purpose. “All of these more private acts of patronage,” Rosenberg explained, “were designed not only to procure delight for the sovereign (although certainly the aesthetic element should never be ignored in this kind of commission), but also to impress those who might have been privileged to enjoy them, by rank or influence.”

We do not know, however, to what extent the Bible of Borso d’Este fulfilled this purpose, because unfortunately no contemporary commentaries survive to assess the impact that the precious codex illuminated by Taddeo Crivelli and Franco dei Russi might have had at the time (commentaries are, after all, the most immediate means one has of assessing the contemporary fortunes of an illuminated codex). One can, however, try to make an estimate on the basis of the information that tells us how well known Borso’s Bible was at the time, which we know for certain was not commissioned for private use only. In fact, we know that in 1467 a certain Niccolò Piatese, an employee of the ducal secretary Ludovico Casella, asked to borrow the Bible to show it to certain “ambassadors from Bologna,” and in 1471 Borso took it with him to Rome to receive the title of duke of Ferrara from the pope, at the end of a very expensive and carefully prepared trip, probably because “he and/or his collaborators thought that the manuscript was an effective tool to convey the image of pious devotion and splendor that the duke sought to cultivate through his travels and his stay at the papal court.”

The historical events, especially recent ones, of the Borso Bible have been reconstructed in a recent essay by Luca Bellingeri. After the devolution of Ferrara to the Papal States in 1598, the fate of the Borso d’Este Bible was common to many other masterpieces of the Este court: the 15th-century codex followed them to the new capital of the duchy, Modena, where it remained until the 19th century. In 1800 it was taken away a first time: Duke Ercole III, in exile from Modena during the Napoleonic invasion, took the precious codex with him to Treviso. After the duke’s death, the Bible passed to his daughter Maria Beatrice Ricciarda d’Este, who later became the wife of Archduke Ferdinand of Habsburg. The Bible returned to Modena several years after the Restoration, in 1831, but it remained there only a short time, since in 1859 Duke Francis V of Habsburg-Este, before finally leaving the duchy that would shortly be annexed to the Kingdom of Italy, took three codices with him to Austria, including the Borso Bible. Ten of these were to return to Italy in 1869 following an agreement between the Italian government and the sovereigns of the preunitary states, but the Bible, the Breviary of Ercole I d’Este and the Officio of Alfonso were recognized as the legitimate property of the Habsburgs. In 1918 the last owner, Charles I, left Austria after World War I to go into exile in Switzerland, taking the Bible with him: after his death, his widow, Zita of Bourbon-Parma, decided to put the codex up for sale, entrusting it to a Parisian bookseller, Gilbert Romeuf.

Neapolitan antiquarian and bibliophile Tammaro De Marinis learned of it, who obtained an option from Romeuf for a sale in Italy, and arranged to inform the Italian government. However, Giovanni Gentile, who had been appointed education minister in the first Mussolini government a few months earlier, let it be known that the treasury did not have the sum to buy the work: however, the industrialist Giovanni Treccani (Montichiari, 1877 - Milan, 1961), who had become the celebrated founder of the Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana in 1925 and had already made himself a leading figure in Italian cultural life in 1919 with a conspicuous donation to the Accademia dei Lincei, came to his country’s rescue. In 1923 Treccani had proposed to Gentile to create a foundation for scientific studies and had already made available a substantial sum, but the minister suggested that he allocate it to the purchase of Borso’s Bible, in which the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York had already expressed concrete interest, declaring itself willing to buy it.

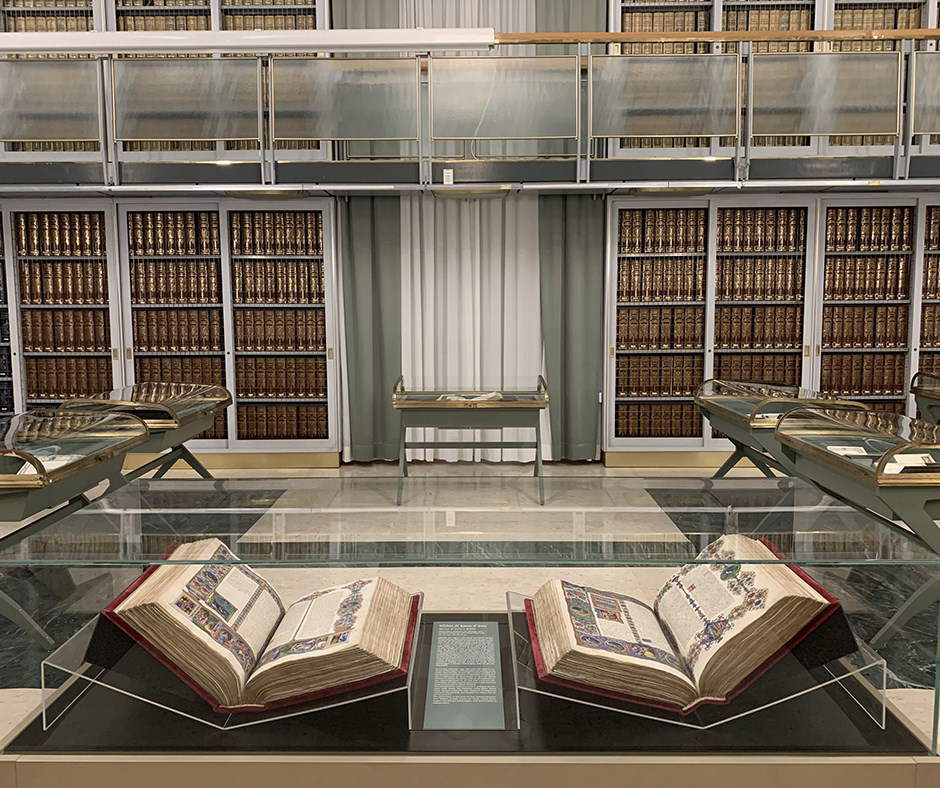

Treccani agreed, and after negotiations with Romeuf, in an act of great generosity, he purchased the Bible for three million three hundred thousand French francs, equivalent to about four million euros today (a commitment double that budgeted for the foundation). The Pierpont Morgan Library offered to buy it for one million francs more than he had paid for it, but Treccani, believing that the Bible should belong to the entire nation, informed Mussolini of his intent to donate the illuminated codex to the state. Four cities had applied to receive it: Modena (as the last place where the Bible was kept before leaving Italy), Rome (as the capital), Milan (as the city where the donor resided) and Ferrara (the city of origin of the Bible). It was the director of the Estense Library at the time, Domenico Fava, who arranged for the Bible to return to Modena: the government eventually decided in Modena’s favor. Only in 1924, however, was the donation formally accepted: in May the Bible reached the Biblioteca Estense, where work began on the “Exhibition Hall” where, Bellingeri recalls, “the permanent Bibliographic Exhibition, conceived by Fava to illustrate the ’treasures’ of the Library, among which, of course, the place of honor would be reserved for the Bible, and on April 19, 1925, in the presence of the two protagonists of the ’recovery’, Giovanni Treccani, who in the meantime had become a senator of the kingdom, and Giovanni Gentile, by then no longer Minister of Public Education, the two volumes were finally displayed in this Room in which, except for the wartime interlude and the 1962 adaptation works they would remain for the next eighty years and still stand today, a true memorable gift for Modena and its Library.”

The institute was founded as a dynastic library and houses the book collection of the Este family, whose origins date back to the 14th century. The original nucleus consists of volumes dating back to the time of Marquis Niccolò III, and was later enriched by the Renaissance rulers (Leonello, Borso, Ercole and Alfonso), who augmented it with very important manuscripts and valuable printed editions. Following the devolution of Ferrara to the Papal States in 1598, the Library was transferred from Ferrara Castle to Modena, which had become the Este capital. In the transfer the Library suffered numerous losses, but new acquisitions and additions succeeded in reinvigorating the institution. In particular, the original nucleus was enriched by the substantial manuscript and especially printed collections from religious suppressions. In 1764, Duke Francis III, in a solemn ceremony, opened the library to the public, and in 1772 he joined it with the University library, with its valuable philosophical, legal and scientific nuclei. After the unification of Italy the two institutions merged, creating what is now the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria.

The legacy of the Dukes of Este is expressed above all through the ancient nucleus of manuscripts, including illuminated dedication specimens, precious philosophical-scientific-literary miscellanies, autograph documents of the personages gravitating around the court, valuable specimens of the ancient art of printing. Also present are an extraordinary musical and cartographic collection. Monuments of the Este miniature include Borso’s Bible, the Genealogy of the princes of Este, Borso’s Missal, Hercules’ Breviary, De Sphaera, Cantino’s Map, and the part remaining in the Estense of the codices dedicated to the dukes, from Candido Bontempi’s Book of the Savior to the epithalamic odes and triumphs. In addition to the works produced within the duchy, the Este enriched the collections with numerous purchases in the markets of Milan, Venice, and Padua: thus, the Corviniani codices, illuminated in Attavante’s Florentine workshop for Matthias Corvinus, king of Hungary, procured by Girolamo Falletti for Alfonso II d’Este; the Greek texts of Giorgio Valla and Alberto Pio; and music repertories such as the codex collecting Italian and French traditions of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, stand out. Numerous acquisitions then interested the Library even after the move to Modena: funds entered, including the Obizzi del Catajo collection, rich in precious miniatures and the Olivetan liturgical codices, and many correspondences such as those of literati like Tiraboschi, Muratori, Cavedoni, Baraldi and those of many scientists, such as Giuseppe Bianchi, Giovanni Battista Amici, and Geminiano Rondelli. On the other hand, the acquisitions of the Formiggini Editorial Archives, the Bertoni collection, the Ferrari-Moreni collection and other heritages that complemented the local collections date back to the twentieth century, further sacing the link between the Bible and the territory.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.