Walking through the endless corridors of the Vatican Museums, now filled with visitors even on winter Tuesday mornings, it is not easy to focus on the most extraordinary works, to grasp the difference between wonder and masterpiece, between the particular and the general. And the signage that (with great care, without affecting now-historicized arrangements) has albeit recently highlighted 100 remarkable works, contributes only in part to orienting the eye of the visitor unaccustomed to modern, contemporary and, even more, ancient art. But we certainly don’t run the risk of not noticing, in the middle of the central corridor of the Pio-Clementino complex, dated to the end of the 18th century, a butt of a statue that for some reason will catch our interest, prompting us to wonder what it is, to bend down to read the caption-a question that has been running through the history of art and Rome for more than 500 years. That anonymous fragment is the so-called Belvedere Torso, and in our curious and amazed gaze is the gaze of so many before us.

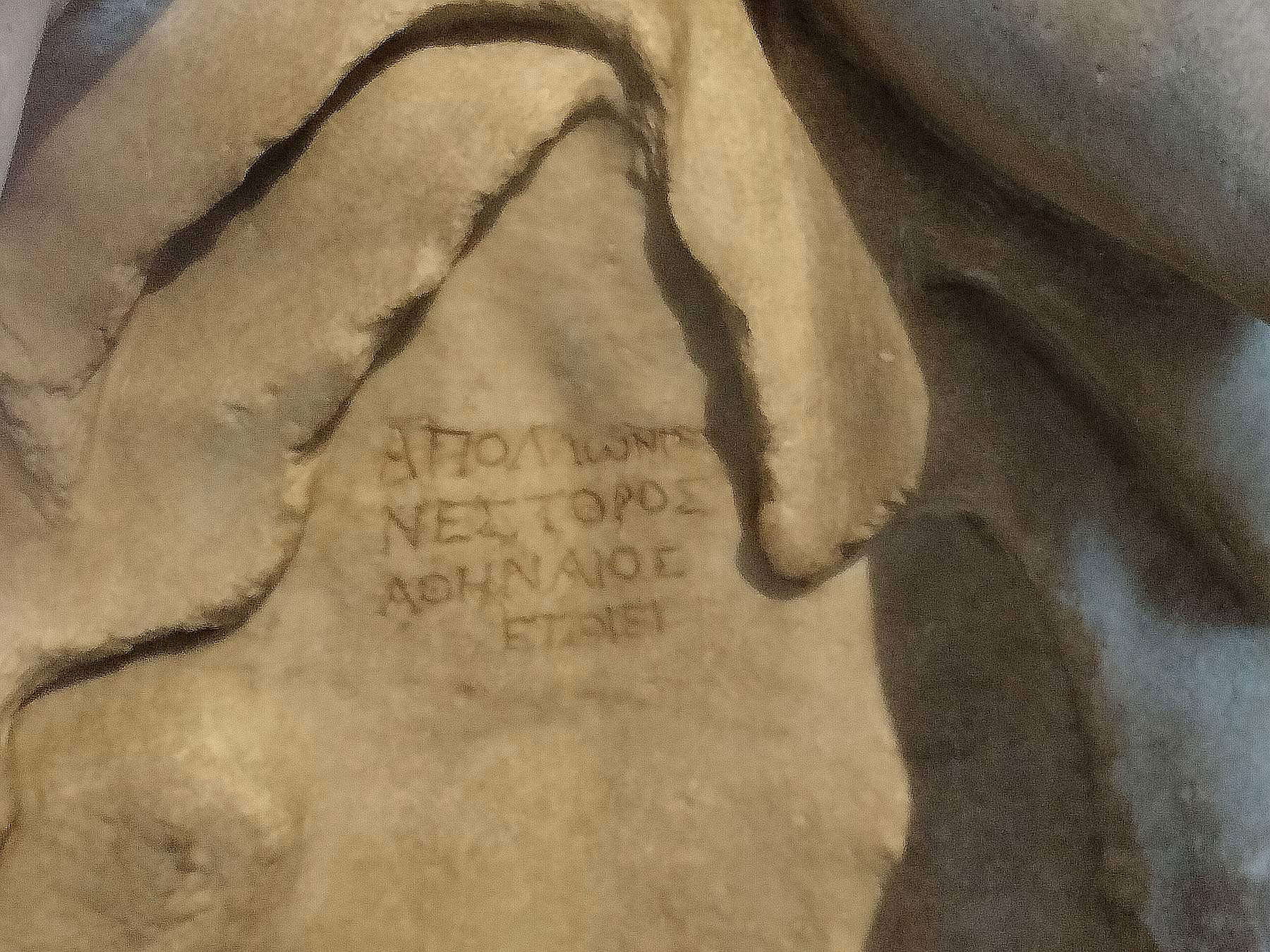

The Belvedere Torso is, in a nutshell, a mutilated statue, a torso and part of the legs. It depicts a man in the act of twisting, leaning on a rock, sitting on a feline (lion?) skin, bent forward. Dated to the first century B.C., it is signed, in Greek, by Apollonius of Athens: a signature that must have been a mark of quality (of workshop, rather than of artist in the modern sense), which indeed the sculpture confirms even at first glance. While entering the realm of subjectivity, we are not dealing with just any Roman-era statue, or even an average one. It is not clear who the subject represented was, although the currently most accepted hypothesis, as we shall see, inclines toward Ajax Telamonius. But in its modern history, the only one known to us, being fragment and being hypothesis has been as much a part of this work as marble.

Known in Rome since the 15th century (the first admiring mention is by Ciriaco d’Ancona, who saw it in Cardinal Colonna’s palace around 1430), the provenance of the Torso is unknown, nor is it known where it was found, although finds at the Baths of Caracalla or in Campo de’ Fiori were recounted by later authors, but the result precisely, it is now clear, of legends or invention. Around 1500, the torso turns out to be in the hands of the sculptor Andrea Bregno, and then, between 1530 and 1536, presumably under the pontificate of Clement VII, it arrived at the place that gave it the name by which we know it today: it entered the papal collections and ended up on display in the Cortile delle Statue originally set up by Julius II, the Belvedere attached to the villa of Pope Innocent III. Here the story of this anonymous marble hero knows the turning point, along with other sculptures that have entered the collective imagination, such as the Laocoon, the Hercules with Telefo, or the Apollo... of the Belvedere. Here the sculpture met on its path Michelangelo Buonarroti, who studied it in all its parts, calling it “the work of a man who knew more than nature,” and making it the model for so many of his figures, particularly in the Sistine Chapel, will give the fragment celebrity for several centuries. Which, mind you, it is by no means obvious to see even today in fragment form: the rule, in the Renaissance and even in later centuries, was to integrate ancient mutilated sculptures. But that did not happen to the Belvedere Torso. Michelangelo, the story goes, refused to integrate it, despite the demands of papal patronage, and no one would dare to do so after him.

The Torso is copied, studied, revisited by many, from Raphael to Rubens, Turner to Picasso, becoming the most cited fragment of ancient art in the history of modern and contemporary art. Winckelmann himself initially did not understand why so much interest in a fragment, but he too would later be converted to admiration of the work. Confiscated by Napoleon in 1797, it would not return to Rome until 1815, thanks to the mediation of Antonio Canova. Today, in the Pius-Clementine complex, thousands of discoveries and finds of Greco-Roman sculpture later, it continues to emanate that power, artistic and otherwise, that so impressed Rome coming out of the Middle Ages: few works succeed in the same way.

But who, then, is effigying that Torso, which became such who knows when and who knows how? The identification has kept artists and critics sleepless for centuries. Although long considered a Hercules (even by Michelangelo himself), given the feline skin, or lion, on which he sits, the iconography actually never persuaded scholars. In later centuries, identifications with Dionysus, Marsyas, Silenus, Philoctetes, Prometheus, among others, were speculated, always without luck. As mentioned above, now the most convincing hypothesis, elaborated a few decades ago from the observations of Raimund Wünsche, is that of identifying the Torso with the Achaean hero Ajax Telamonius, caught in the act of meditating suicide, after having received the humiliation of not receiving Achilles’ weapons, and having gone mad.

According to this hypothesis, the Mutilated Torso would show the hero with his head bowed, back arched, his right arm gripping the sword on which he would throw himself a little later. It is an image that recurs many times, according to what archaeologists have reconstructed, in vases, gems, pastes and paintings made by artists and craftsmen who were inspired by that tragedy back in antiquity. An iconography that would have been fixed by a funerary monument of the hero himself, a bronze statue dated between 188 and 167 B.C. and placed in front of Troy by the people of Rhodes, which is known to have been so famous and admired that Mark Antony took it to Egypt as a gift for Cleopatra. Augustus ordered a marble copy to be brought to Rome: the one that, according to Wünsche and others, would become the Belvedere Torso. A solid, broad hypothesis, even though it has not persuaded all scholars: the Torso, thus mutilated, may continue to be known as the Torso for centuries to follow. In a monument to the unfinished that Apollonius of Athens would never have thought of producing.

The author of this article: Leonardo Bison

Dottore di ricerca in archeologia all'Università di Bristol (Regno Unito), collabora con Il Fatto Quotidiano ed è attivista dell'associazione Mi Riconosci.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.