According to a famous anecdote reported by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives, today we no longer have the cartoon of the Battle of Cascina by Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) because it was allegedly destroyed by Baccio Bandinelli (Bartolomeo Brandini; Florence, 1488 - 1560), his rival, who hated him but tried throughout his life to imitate his art, without succeeding, and who preferred Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) to him. According to the account Vasari provides in the Torrentine edition of the Lives (withdrawn, however, in the Giuntina edition), Bandinelli, in 1512 during the events that led to the fall of the Florentine Republic and the restoration of the Medici family, allegedly sneaked into the Sala del Consiglio Grande (i.e., the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, where the cartoon was located) with the deliberate intent of tearing the work to pieces, succeeding. About the reasons, Vasari also wondered: “Frequenting more than all others the place Baccio et having the key forged, it happened at this time that Piero Soderini was deposed from the government lanno 1512 and put back in state the house of Medici. In the tumult addunque of the palace for the renewal of the state, Baccio by himself secretly tore the cardboard into many pieces; of which the cause was not known, some said that Baccio had torn it in order to have some pieces of the cardboard in his own way behind him: some judged that he wanted to give young people that commodity so that they would not have to profit and make themselves known in art; some said that the influence of Lionardo da Vinci, to whom the Buonarroto cartoon had taken away much reputation, moved him to do this; some, perhaps interpreting it better, gave the cause to the hatred he bore for Michelagnolo, as he then showed throughout his life. It was the loss of the cardboard to the city not small et the burden of Baccio very great, which was deservedly given him by each and every one and dinvidioso and malignant.”

Bandinelli’s (or whoever’s) action, however, was not so destructive as to prevent us from getting copies of Michelangelo’s work, which was part of the ambitious decoration of the Salone dei Cinquecento desired by the Republic a few years earlier: in fact, the gonfaloniere, Pier Soderini, intended to adorn the walls of the great hall where the Maggior Consiglio di Firenze (a kind of parliament composed of five hundred citizens, established in the Savonarolian age and then maintained even after the fall of the Ferrarese friar) met with scenes of battles won in the past by Florence. In October 1503, the Republic had commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to paint the Battle of Anghiari(full history of the work here): on October 24, the vincian artist, back home, took up residence in the Sala del Papa in Santa Maria Novella where he would work on the cartoon, while on May 4, 1504, he signed the final contract. Michelangelo was instead hired for the Battle of Cascina, which was to be painted on the opposite wall, between August and September 1504. For Michelangelo, too, the Republic provided lodging: “Michelagnolo,” Vasari recounts, “had a room in the Spedale de’ Tintori in Santo Onofrio, and there he began a very large cartoon: nor, however, did he ever want others to see it.” The young sculptor probably felt rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci, and it is Vasari himself who puts it on this level, narrating that “it was the cause that he made in competition with Lionardo the other facade, in which he took as his subject the war of Pisa.” The two paintings, as mentioned, were supposed to decorate the great hall built at Savonarola’s behest between 1495 and 1496, in just seven months, to a design by Simone del Pollaiolo known as il Cronaca and Francesco di Domenico.

The battle assigned to Michelangelo had a high symbolic value: it was a clash fought between the Florentines and the Pisans and won by the former, and in 1504 Pisa, although it had been annexed to Florence for almost a century, was a rebellious city. In 1494 the Pisans had tried to regain their freedom by taking advantage of Charles VIII’s descent into Italy: however, the French king held an ambiguous attitude, supporting Pisa so as not to be hindered in his own descent to Naples (the Pisans thus succeeded in ousting the authorities of Florence from the city’s dominion), except that he then worked to ensure that Pisa returned under Florence. However, the Pisans continued their revolt, reaching a clash with Florence in 1496: a stalemate ensued, partly because Pisa had obtained the support of some foreign powers. And it was precisely in 1504 that the Florentines thought of diverting the course of the Arno in order to weaken Pisa: it has been speculated that for the project, the so-called “Arno route,” which Florence believed would be decisive in defeating the rebellious city, the advice of Leonardo da Vinci had also been sought, at the very time when the artist was engaged in the Battle of Anghiari. Actually, we don’t know for sure: the long debate about his participation in the “Arno rout,” however, has leaned toward his probable non-involvement (Leonardo’s drawings on the channelization of the Arno therefore would have nothing to do with this project). In any case, the idea of diverting the course of the river failed, and Florence managed to get the better of Pisa in 1509 through a military reconquest. But at the time Michelangelo was asked to fresco the ancient battle between Florence and Pisa, the clash was still open. In any case, we know for a fact that in 1504 Leonardo carried out some surveys in the plain of Pisa, and the situation may have distracted him for a few weeks from the Salone dei Cinquecento assignment. And since the paintings had propagandistic intent, they had to be completed quickly: and it is perhaps also for this reason (or because of Leonardo’s slowness) that the Republic decided to pair him with the young Michelangelo.

|

| The Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Ph. Credit Targetti Sankey |

At the time, Leonardo was an accomplished artist of fifty-one, Michelangelo, on the other hand, was a twenty-eight-year-old who had already created a number of important masterpieces, so he had little to prove, and he had his young age on his side, which probably increased his cockiness. The two artists, after all, could not have been more different: Leonardo was a very handsome, pleasant and sociable man, of bourgeois origins although the son of an illegitimate relationship, open to the world, curious and eager to know, very generous. Michelangelo was the opposite: not very handsome in appearance, irascible and lonely but always with a ready answer, from a family of noble origins but which had fallen into decay over the decades, extremely proud and contemptuous, thrifty to a fault, prone to misanthropy but prone to overwhelming feelings for the people he loved. The two got to know each other shortly before the commissioning of the Salone dei Cinquecento, and corroborating the topos of their clash is an anecdote recounted by theAnonimo Magliabechiano (and not traceable in any other source) in a codex preserved at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, where we find this passage: “Et passando ditto Lionardo, insieme con G. da Gavina, from Santa Trinita by the pancaccia delli Spini, where there was a gathering of men of good, et where a passage of Dante was disputed, I called said Lionardo, telling him that I declared that passage to them. And by chance, at point Michele Agnolo passed by there, and called by one of them, Lionardo answered, ’Michele Agnolo will declare it to you.’ Whereupon, seeming to Michael Agnolo that I had said it to mock him, with wrath he answered him: ’Declare it as well you, who made a design of a horse to cast it in bronze and could not cast it, and for shame you left it alone.’ And having said this, he turned his kidneys to them and went away. Where remained Lionardo, who by the said words turned red.” In short, Leonardo had been asked by some friends to recite some verses of Dante, and the vincian, seeing Michelangelo passing by, told them to ask him: whereupon the sculptor, thinking that Leonardo was making fun of him, allegedly answered him in a nasty way by holding the fiasco of the equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza against him.

Even Vasari lets it be known that there was “very great disdain” between the two, to the point of motivating, on the basis of this disagreement, Leonardo’s departure for France in 1516. In reality, beyond the anecdotes, reported only by biographers (the topos of clashes between artists in any case fills the pages of Vasari and the art writers of the time, reasoning that some episodes could be highly charged), there are no documented reasons that could suggest a clash between the two. The only possible (and documented) reason for a disagreement (although we do not actually know how Michelangelo might have taken it) might be the proposal that, in 1504, Leonardo da Vinci, called to join, along with all the great Florentine artists of the time, the commission that was to decide on the placement of the young rival’s David, put forward for the sculpture, proposing that it be placed against the back wall of the Loggia dei Lanzi. A position that might have been considered unfortunate (the statue would have had little visibility), but which was consistent with Leonardo’s artistic choices, as scholar Edoardo Villata has explained: “Leonardo seems to have wanted to translate into painting, in full consistency with what he was writing about the effect of relief as the highest end of pictorial activity, his proposal to place the David against the back wall of the Loggia dei Lanzi, not dissimilarly to the visual effect.”

Leonardo and Michelangelo were, yes, characteristically very different, and probably not even compatible: but about their relations we cannot make too detailed assumptions, and since biographies of the time tend to exaggerate for narrative purposes certain aspects of the artists’ lives, it is also likely that the portraits that emerge from Vasari and the Anonimo Magliabechiano exaggerate an antipathy that is perhaps not invented, but which we do not know how much it affected their respective careers (as one might intend by reading Vasari instead). What we can say with certainty, however, is that the works that Leonardo and Michelangelo executed for the Salone dei Cinquecento, although both unfinished (Leonardo because of technical problems, Michelangelo because he abandoned the project), were held in very high esteem by their contemporaries, and judged to be extraordinary masterpieces: it will suffice to recall how another great artist of the time, Benvenuto Cellini, had written that the two cartoons were “the school of the world,” because all the artists in Florence at the time went to train by observing them, as is also attested by the various copies and takes from Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s ideas, from Raphael to Sodoma, from Marcantonio Raimondi to Fernando Llanos, thus contributing to the great diffusion of the models of the two artists.

|

| Daniele da Volterra, Portrait of Michelangelo (c. 1544; oil on panel, 88.3 x 64.1 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

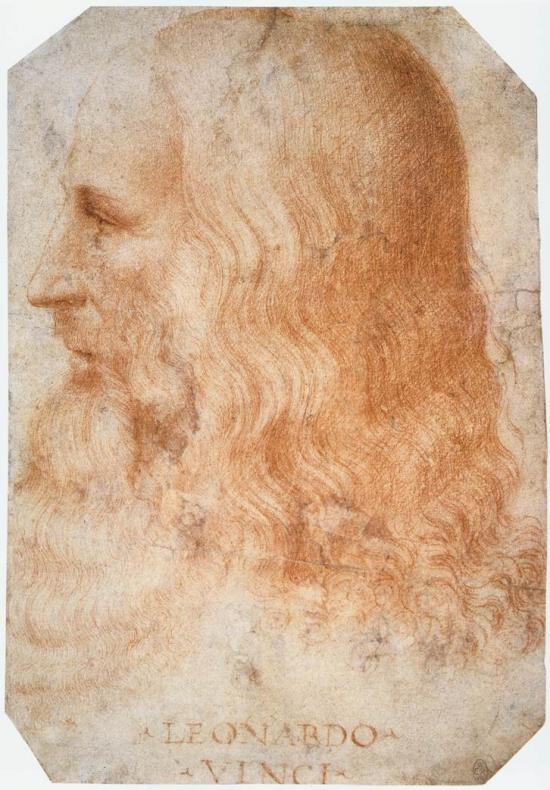

| Francesco Melzi, Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1510; sanguine on paper, 275 x 190 mm; Windsor, Royal Collection) |

|

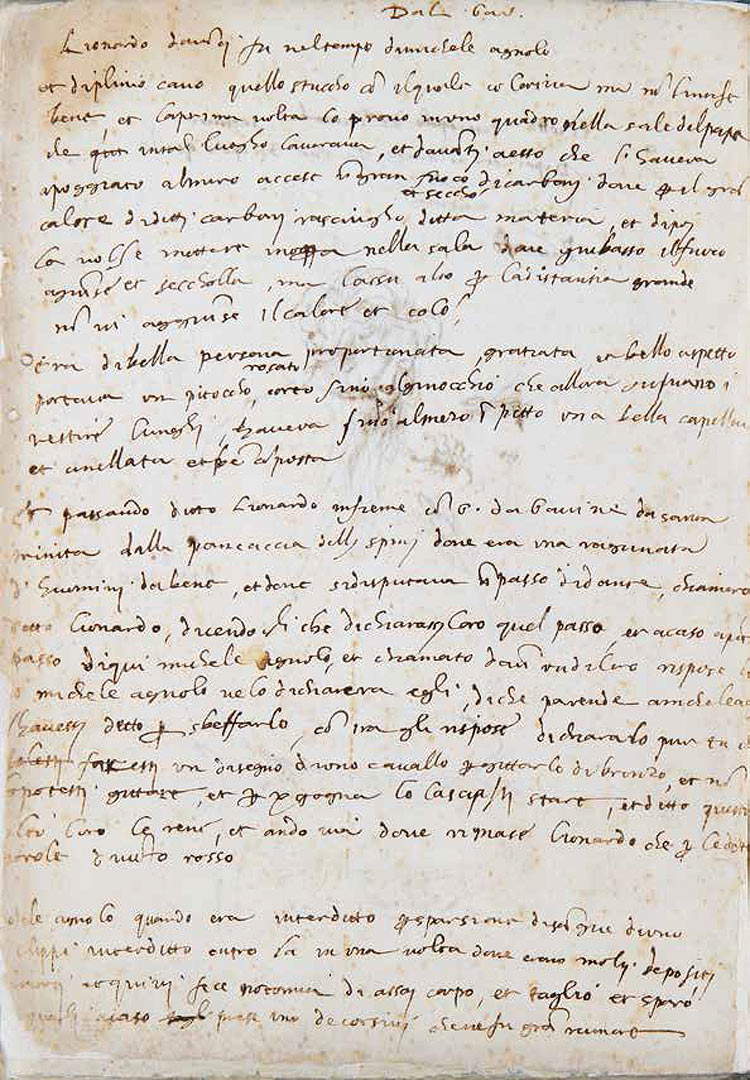

| The anecdote of the clash between Leonardo and Michelangelo reported in the codex dellAnonimo Magliabechiano (Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. Magliabechiano, XVII, 17, 121v) |

|

| Michelangelo, David (1501-1504; marble, height 517 cm including base; Florence, Galleria dellAccademia) |

The Battle of Cascina was fought on July 28, 1364 between Florence and Pisa, at the time of the war between the two Tuscan cities. The Pisans were led by two strong captains of fortune, the Englishman John Hawkwood (Sible Hedingham, c. 1320 - Florence, 1394), or the “Giovanni Acuto” who would pass with the Florentines at the end of his career, buried in Santa Maria del Fiore and eternalized in Paolo Uccello’s equestrian portrait, and the German Hanneken von Baumgarten (? - 1375), known in Italy as Anichino di Bongardo. Prior to the Cascina clash, the Pisans captained by Hawkwood and Baumgarten had inflicted several defeats on the Florentines, who decided to reorganize the army by entrusting its command to the Romagna condottiero Galeotto I Malatesta (Rimini, c. 1300 - Cesena, 1385), who could count on the help of the Marquis of Soragna, Bonifacio Lupi (Soragna, 1316 - Padua, 1390), an ally of the Florentines. The clash took place, in the middle of summer, on the banks of the Arno on a very hot day: according to the chroniclers’ account, the Florentines, halted near Cascina, had allowed themselves a moment’s rest on the banks of the Arno, and many soldiers took to bathing in the waters to refresh themselves from the heat. Malatesta, too, decided to rest and entrusted the organization of the defenses to Bonifacio Lupi and Manno Donati, who placed some soldiers on the road to Pisa, who were immediately attacked by the Pisans to test the resistance of the Florentines. Hawkwood waited until the sun was in his opponents’ faces to have an advantage in the clash, and tried to organize a surprise attack, which was, however, foiled by the Florentines: the Pisan army, composed mostly of German and English soldiers unaccustomed to the heat, could not sustain the clash, and Florence won a clear victory, with one thousand fallen in the enemy army and two thousand prisoners (the foreigners released, and the Pisans taken to Florence). Michelangelo depicted the moment when the Florentine soldiers, still intent on bathing in the Arno, are suddenly called back to battle because of the oncoming enemy.

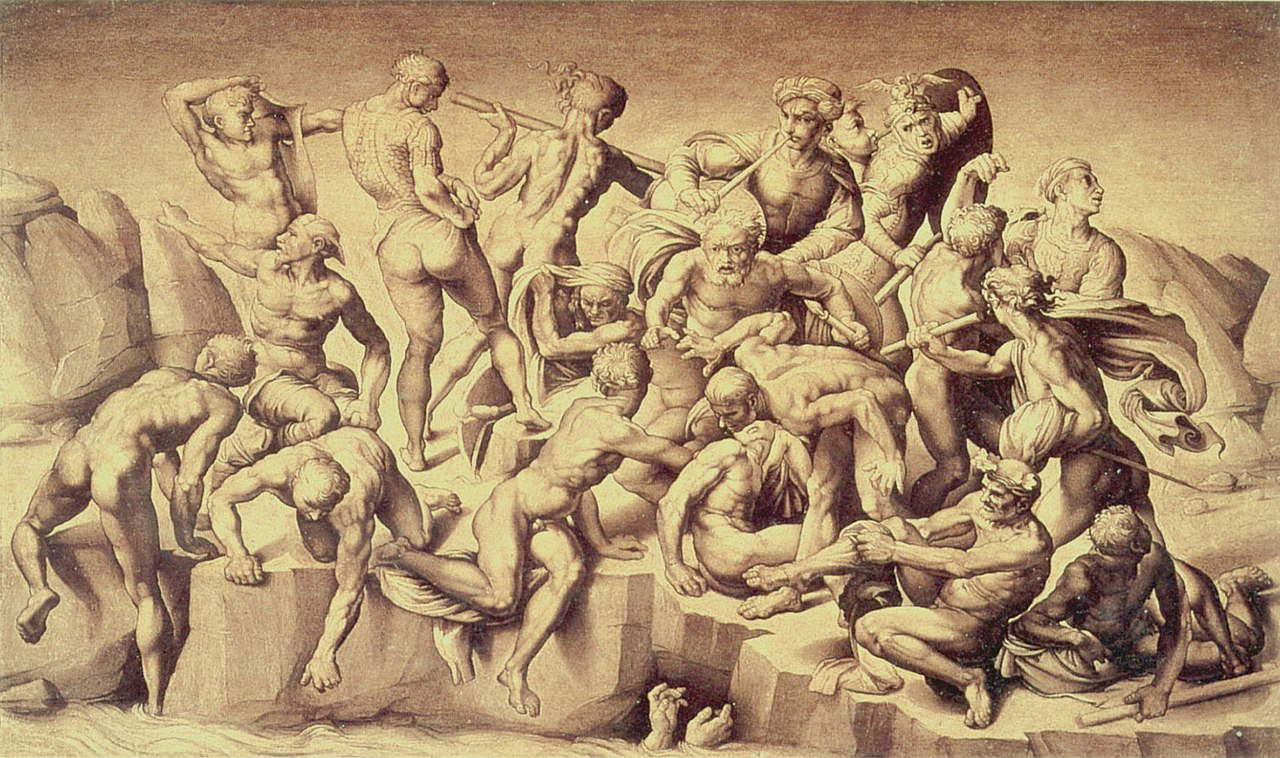

The particular iconography allowed Michelangelo to produce a depiction of finely anatomically studied nudes: the artist got to experiment with a great variety of poses and attitudes, among soldiers lying down, others who are getting up, one who forces his arms to hoist himself onto the riverbank, one who raises his arms to slip on his armor, one who is already unsheathing his sword, one who runs, one who leans out, one who is still submerged in water and whose hands are only visible, and an old man who tries to slip on his stockings but succeeds poorly in his intent because his legs are wet after bathing in the river. This last detail was much appreciated by Vasari, who gives us an extensive description of the work: "E lo empié di ignudi, che bagnandosi per lo caldo nel fiume dArno, in quel stante si dà a larme nel campo, fingendo che gli inimici assalissero li; e mentre che fuori delle acque uscivano per vestrsi i soldati, si vedeva dalle divine mani di Michelagnolo chi affrettare lo armarsi per dare aiuto a compagni, altri affibbiarsi la corazza e molti mettersi altre armi indosso, et infiniti combattendo a cavallo cominciare la zuffa. There was among the other figures an old man, who had on his head to shade himself a grill made of ivy, who, when he sat down to put on his stockings, and they could not fit him because his legs were damp from the water, and hearing the tumult of the soldiers and the shouts and the roars of the drummers, hastening pulled by force a stocking; et oltra che tutti i muscoli e nervi della figura si vedevano, fare una storcimento di bocca per il quale dimostrava molto quanto e pativa e che egli si durava fino ai punte de piedi. There were drummers again, and figures who, with wrapped cloths, unclothed, ran toward the baruffle; and of extravagant attitudes one could see some standing upright, some on their knees, or bent or suspended to lie, and in the air attached with difficult iscourses. There were also many figures grouped together and sketched in various ways, some outlined with charcoal, some drawn with strokes and some shaded and highlighted with white lead, wanting to show how much he knew in this profession.

The work is reminiscent of a youthful masterpiece by Michelangelo, made when the artist was little more than 15 years old, namely the Battle of the Centaurs now at Casa Buonarroti(more on that here), and exactly as was the case with the Battle of the Centaurs, "the historical datum , scholar Angelo Tartuferi has written, “is used above all to imagine a fantastic brawl of naked bodies with stupendously delineated anatomy, once again reconfirming the primacy of drawing that characterizes all Florentine Renaissance artistic culture.” The effect, undoubtedly intended, Cristina Acidini also reiterated, is that of "a tangle of bodies agitated by violent motions, consistent with research pushed to the limit of virtuosity in the youthful relief of the Battle of the Centaurs." Compared to the youthful Battle of the Centaurs, however, there is an extra element, namely precisely that strong narrative dimension that motivates the dynamic sequence “despite the apparent frenzy,” as Cristina Acidini noted again: “from the foreground, where it is the nudes ascending the rocky prod, helping each other, one’s gaze is drawn to an intermediate plane where there are those who are drying and those who are dressing, those who are raising the alarm and those who are responding, while toward the back the nudes are alternating with soldiers wearing their weapons or already in battle gear and the trumpets incite the troop by blowing into their instruments.” Another reference is given by the nudes that populate the bottom of the Tondo Doni and thus constitute another important precedent for the Battle of Cascina.

Michelangelo’s work is known to us today from copies taken from the cartoon: the most famous and probably closest to the lost original is the one executed around 1542 by Bastiano da Sangallo (Florence, 1481 - 1551), a pupil and collaborator of Michelangelo’s, now preserved at Holkham Hall in the collection of the Earl of Leicester. On an artistic level, too, Michelangelo’s work is very different from Leonardo’s: both were meant to be frescoes of political propaganda, but while Leonardo resolves the theme with sophisticated allegories, cloaking the subject with his own personal ideas and without renouncing cultured classical references, Michelangelo focuses instead on a kind of physical heroism, that of the soldiers who, called to battle, immediately get out of the Arno and rush to fight, without any particular metaphorical subtleties. On the contrary: Michelangelo’s language makes exclusive use of body, muscle, power. An unusual bodily vigor for Leonardo as well: both artists had approached the theme proposed by the Florentine Republic in innovative ways, but using different languages that exerted a remarkable fascination on all the artists who were fortunate enough to see their works.

|

| Bastiano da Sangallo, Battle of Cascina, copy from Michelangelo’s cartoon (c. 1542; panel, 78.7 x 129 cm; Wells-next-the-Sea, Earl of Leicester Collection, Holkham Hall) |

|

| Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs (c. 1490-1492; marble, 80.5 x 88 cm; Florence, Casa Buonarroti, inv. 194) |

|

| Michelangelo, Tondo Doni (1506-1507; tempera grassa on panel, 120 cm diameter; Florence, Uffizi Gallery). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

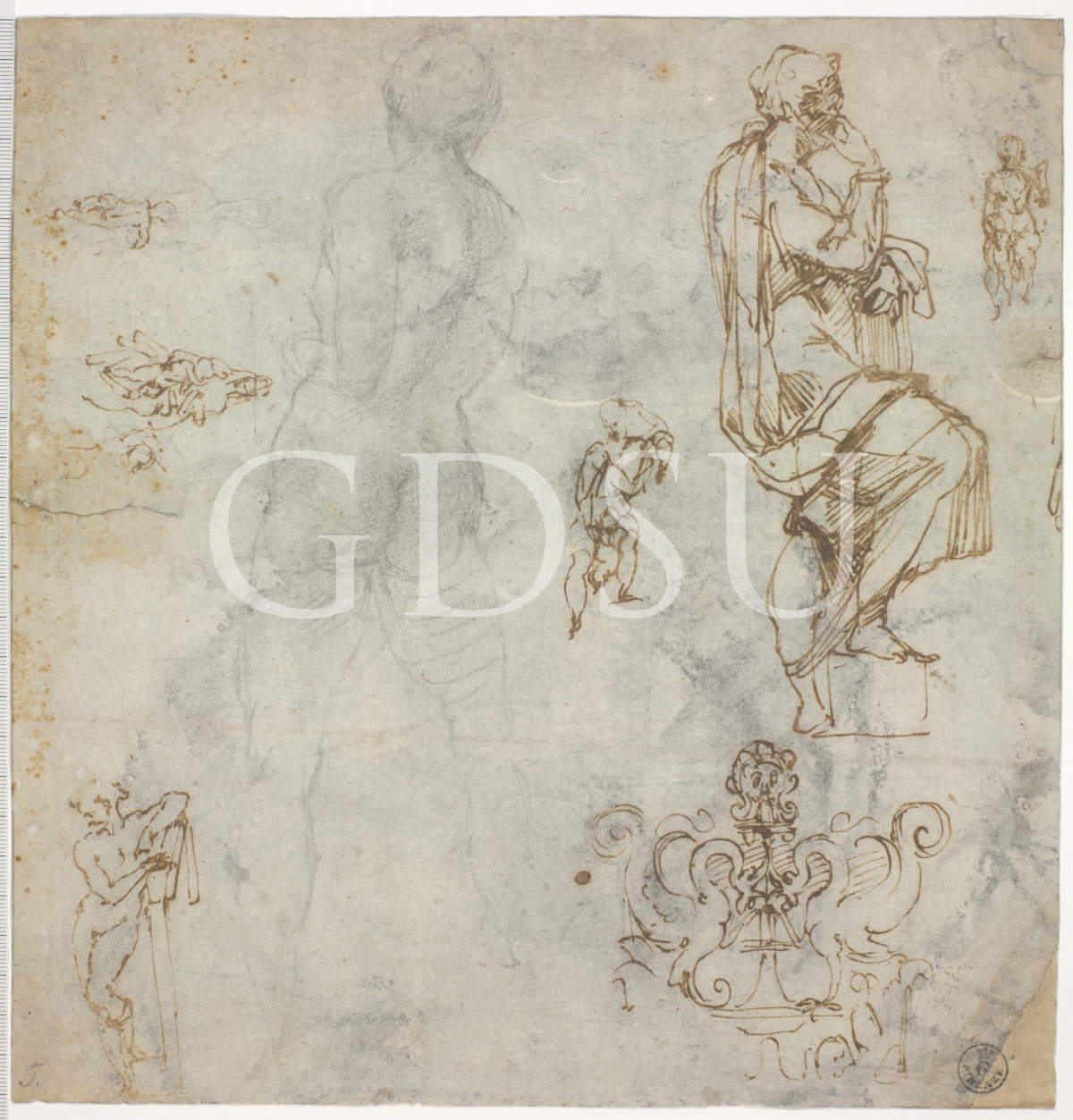

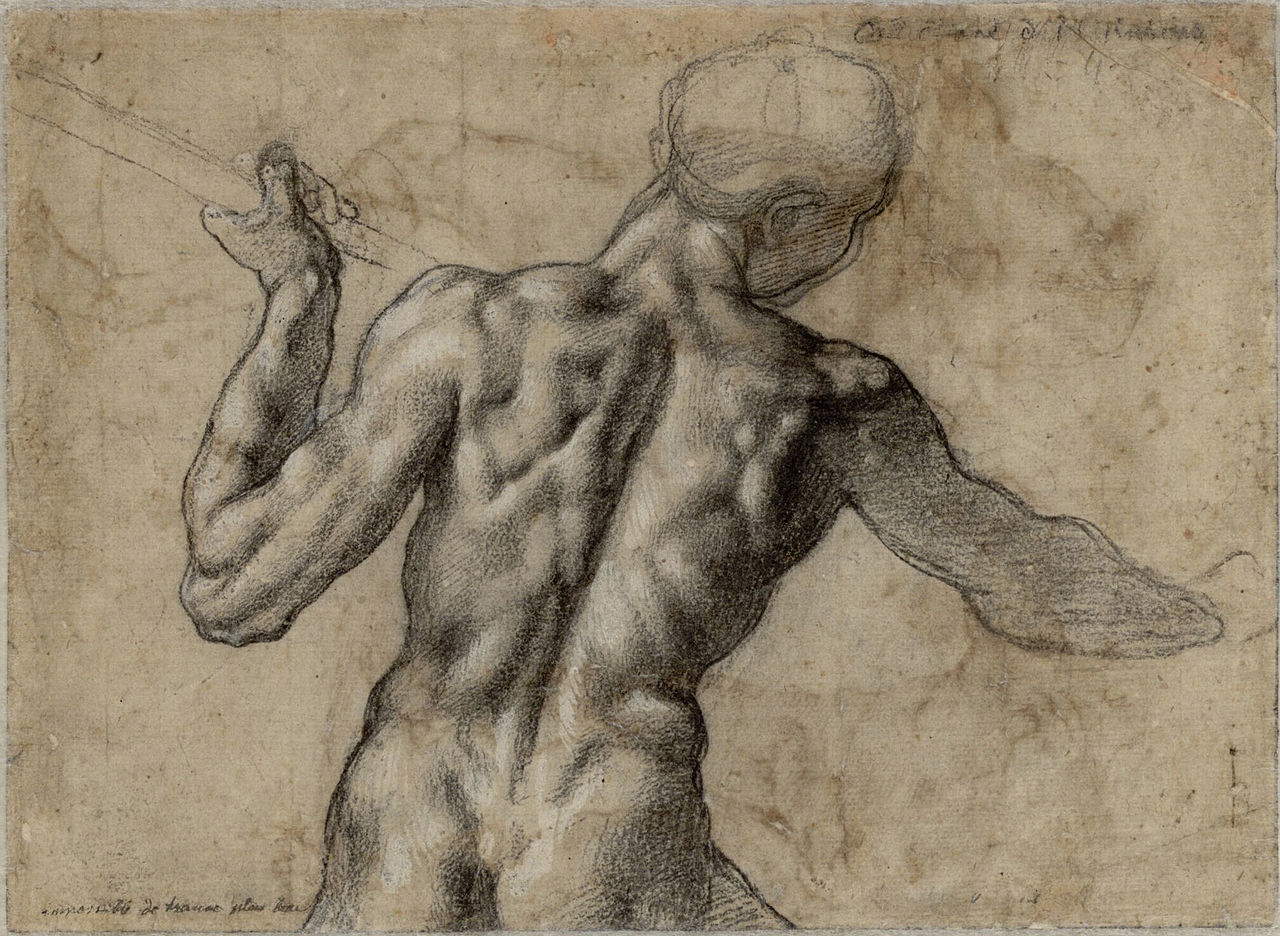

We have lost the Michelangelo cartoon, but we preserve several drawings and sketches that Michelangelo made to study the composition. However, points of contact with Leonardo emerge from these studies, beyond the choice of subject (the Vincentian was going to paint a scuffle between soldiers on his wall, and Michelangelo would paint another scrum on the opposite wall). The sheets made in preparation for the Battle of Cascina, scholar Antonio Mazzotta has written, demonstrate Michelangelo’s “insistence on the study of the male human body”: in the drawings for the never-realized fresco, “the artist practices a skill of black pencil blending and chiaroscuro that harks back to Leonardo’s drawing technique.” Other drawings, however, reveal typically Michelangelo-like constructions, with large, vigorous figures marked by a very pronounced outline, detailed anatomical studies, and strong chiaroscuro. This can be appreciated, for example, in folio 233F in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi, identified as a “worksheet” by Michelangelo by Paola Barocchi: we find, in its center, a nude from the back, a preliminary study for a figure from the Battle of Cascina. It is a nude that also recurs in other sheets, preserved in the British Museum and the Louvre, although the artist later dispensed with it in the final cartoon. Another very famous drawing (perhaps the best known of the studies for the Battle of Cascina) is 73F preserved at Casa Buonarroti: it is another back nude, caught in the moment of momentum, and appreciable for the muscular tension that animates the male body, depicted with his leg about to take a leap and his right arm raised. It is perhaps from these studies that Michelangelo’s relationship with antiquity is also best appreciated: several cues were drawn from classical statuary, and in particular from the Roman sarcophagi that the artist was able to study in Tuscany and Rome.

The figure of 73F from Casa Buonarroti finds a timely match in folio 613 E of the Uffizi, where we see a study for the composition, different, however, from the drafting of the final cartoon known from the copies: in this sketch the confusion of the melee prevails, the tangle of bodies is denser, the poses seem almost more daring. Some solutions experimented with in this first proof will thus be abolished (including the figure caught in the act of soaring). However, there are also drawings where we see the figures that Michelangelo later uses in the final version: for example, the man seen bare-chested, from behind, wielding a spear, which we see punctually studied in a drawing preserved in the Albertina in Vienna, where we appreciate the muscles placed in relief, studied individually, highlighted even by slight highlights, to impart an additional sense of strength to the figure. Few other artists were able to create such powerful drawings.

|

| Michelangelo, Study Sheet for Apostles, Battle of Cascina, Madonna of Bruges and an Architectural Element (1503-1504; natural black stone, sfumino, pen and ink, traces of lead tip on paper, 273 x 262 mm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, 73 F) |

|

| Michelangelo, Back Nude (c. 1504-1505; pen and black pencil traces, 408 x 284 mm; Florence, Casa Buonarroti, inv. 73 F) |

|

| Michelangelo, Study of Composition for the Battle of Cascina (c. 1504-1505; pen and silver point on paper, 235 x 356 mm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, 613 E) |

|

| Michelangelo, Back Nude (c. 1504-1505; pen and chalk, 196 x 270 mm; Vienna, Albertina) |

What was the fate of the Battle of Cascina? We can assume that in the spring of 1505 the cartoon was ready, but on April 17, 1506, Michelangelo left for Rome to work for Pope Julius II, and would not return to Florence for the next ten years. The fresco, therefore, was never completed. It is likely, however, that the preparatory work was also unfinished: biographers, including Giorgio Vasari and Benedetto Varchi, refer to compositions hinting at a clash between Florentines and Pisans, and Michelangelo’s own drawings attest to figures of knights in combat. It is therefore likely that Michelangelo painted only one episode of the battle, without completing any other scenes. That single episode, however, had an extraordinary fortune that also spread thanks to the engravings that were made from it. It has already been mentioned that Cellini had called Michelangelo’s and Leonardo’s cartoons “the school of the world,” and Vasari attests that some of the greatest artists of the time went to study Michelangelo’s work: Raffaello Sanzio, Bastiano da Sangallo, Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Baccio Bandinelli, Francesco Granacci, Alonso Berruguete, Andrea del Sarto, Franciabigio, Iacopo Sansovino, Rosso Fiorentino, Pontormo, Perin del Vaga, and others.

We know that after Michelangelo’s departure for Rome, the cartoon was kept under lock and key: in fact, there are a couple of letters that Michelangelo sent to his brother in 1508 recommending that Alonso Berruguete show the work. Instead, it is from 1510 that Francesco Albertini ’s memorial attests to the presence in Palazzo Vecchio of “li disiegni di Michelangelo,” along with “li cavalli” by Leonardo da Vinci. However, the work was removed from Palazzo Vecchio in 1512, the year of the Medici restoration: in the seat of power it was not possible for a symbol of republican Florence to remain. Vasari thus relates that the cartoon “was taken to the Medici house in the great hall above, and such a thing was the cause that he too much a securtà in the hands of the artisans was put; for that in the infirmity of Duke Giuliano, while no one was paying attention to such a thing, it was, as has been said elsewhere, torn and divided into many pieces, such that in many places it disappeared, as some pieces that can still be seen in Mantua in the house of Messer Uberto Strozzi, a Mantuan gentleman, which are held with great reverence, bear witness to this.” According to the Aretine historiographer, it would thus have been Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours (Florence, 1479 - 1516), whose funeral monument, moreover, would have been made by Michelangelo himself (it is one of the masterpieces in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo), who had the cartoon removed from Palazzo Vecchio. At a later date, the cartoon would have been cut up: perhaps by Baccio Bandinelli, as Vasari suggests in the Torrentine edition of the Lives (withdrawing the information in the 1568 edition, however: it is, after all, well known that there was bad blood between Vasari and Bandinelli), perhaps by others, but it is a fact that at a given juncture in history all that remained were shreds of the original cartoon of the Battle of Cascina, perhaps torn apart by admirers who wanted to possess a piece of the work of that great artist so highly esteemed by his contemporaries. Vasari, after all, wrote that the things Michelangelo had drawn in the cartoon “a vedere e son più tosto cosa divina che umana.” And the astonishment of his contemporaries in front of that singular and powerful work are all revealed, again, by the words of the artist from Arezzo: “Per il quale gli artefici stupiti et ammirati restorono, vedendo lestremità dellarte in tal carta per Michelagnolo mostrata loro. Onde veduto così divine figure, dicono alcuni che le viddero, di man sua e daltri ancora non essere mai veduto più cosa che della divinità dellarte nessuno altro ingegno possa arrivare maiarla.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.