The Battle of Anghiari: from Leonardo's masterpiece to the landscape witness of the

The Battle of Anghiari, although a rather important historical episode, would not be a well-known fact to most people today if it did not tie its memory to Leonardo da Vinci and the famous painting that the genius from Vinci allegedly began and never completed for Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Of all the lost works in history, that of Leonardo’s Battle is an absence that has never given peace and to this day continues to cause consternation: professionals who cyclically swear they have found some original, whose memory had been lost or mistaken for a late replica, or those who persistently propose hyperbolic as much as redundant reconstructions, still others find alliance in politics, always careful not to lose whatever springboard might grant them some prestige and dispose themselves under intuitions imbued with Dan Brown-like imagery to chisel away at a fresco to free the prodigal son, because anyway, let’s face it, a Leonardo or even his feeble promise is well worth a Vasari. We are not ready to resign ourselves to the fact that works of art have a life like that of living things, sometimes certain it can last frighteningly longer, and fortunately so, sometimes fortuitous or otherwise reasons have arranged its termination.

So, how to cope with it? Study and research can ease our pains, but then if that is not enough there also remains the context, about which Quatremère de Quincy masterfully knew how to open Europe’s eyes, when the emperor of the day wanted to remove its wonders and lock them up in a gray museum: “The real museum of Rome, the one of which I speak, is composed, it is true, of statues, of colossi, of temples, of obelisks, of triumphal columns, of baths, of circuses, of amphitheaters, of triumphal arches, of tombs, of stuccoes, of frescoes, of bas-reliefs, of’inscriptions, fragments of ornaments, building materials, furniture, tools, etc. etc. but nevertheless it is composed of the places, the sites, the mountains, the roads, the ancient streets, the respective positions of the ruined city, the geographical relations, the relations between all the objects, the memories, the local traditions, the still existing customs, the comparisons and the comparisons that cannot be made except in the country itself,” and again: “What artist has not felt in Italy that harmonious virtue between all the objects of the arts and the sky that illuminates them; and the country that serves them almost as a background; that kind of charm that beautiful things communicate to each other, that natural reflection that the models of the various arts, placed in front of each other, procure for themselves in their native country?”

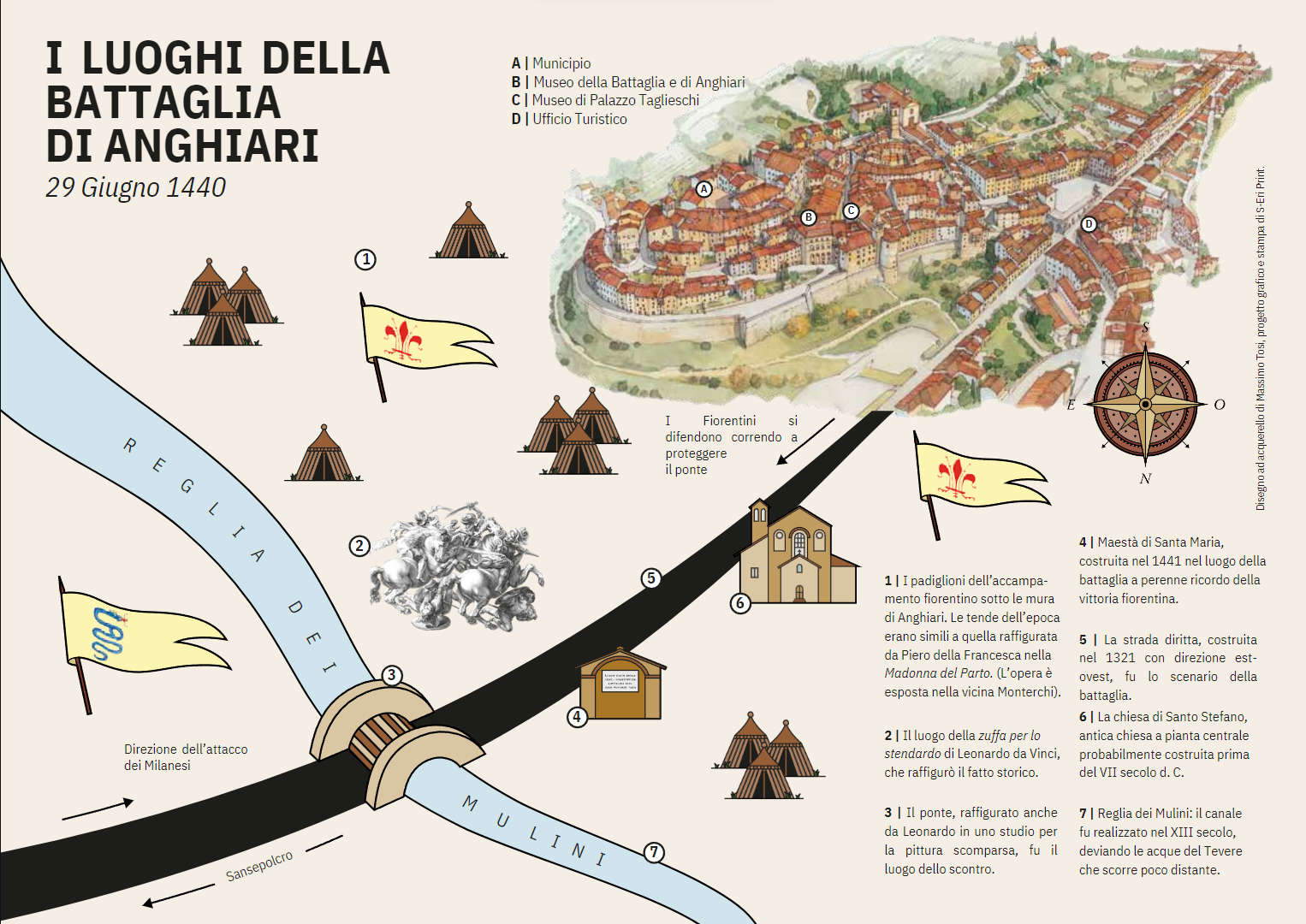

And so in what we call context we can perhaps find the balm to our wounds, and in the case of the Battle of Leonardo we certainly have more avenues for consolation-if on the one hand there is that well-known diffuse museum that is Florence, which awaited the feat of the Tuscan painter and inventor, on theother there is the no less significant landscape made up of inextricable references and stories that witnessed the infamous historical episode of the Battle, and that luck and perhaps a little foresight would have it not be lost, amidst splendid views and a heritage that is still extraordinarily tangible.

The Battle of Anghiari, which was fought in 1440, is a rather relevant event in Italian history, since it saw the army of the Visconti of Milan facing off on one side and a coalition led by the Florentine Republic on the other, but which also saw papal troops and those of Milan’s sworn enemy, the Serenissima of Venice, on the field.

Florence had an ambiguous attitude, not uncommon at that precise moment in history, switching sides, finding itself allied with the Republic of Venice and the Papal States, no longer led by Pope Martin V, of strong Florentine antipathies, but succeeded to the papal throne by the Venetian Eugene IV. This understanding had arisen under fear of the hegemonic aims of the Duchy of Milan.

Having failed in his ambitions to annex Brescia and Verona, Visconti resolved to attack the strategically important Florentine territories, since they were crossroads between central Italian possessions, and to simultaneously weaken the ally of Venice. In an age of profound wealth, wars in Italy were fought by soldiers of fortune, professional fighters in the pay of the powerful, who certainly did not shy away from changing their coats as needed. The Milanese availed themselves of the Peruvian condottiere Niccolò Piccinino, who crossed the Apennines on April 10, 1440, arriving in Mugello, where he severely sacked several towns and villages. The Florentines for their part had assembled a coalition army, whose leaders included Pietro Giampaolo Orsini, Micheletto Attendolo and Ludovico Scarampo Mezzarota.

There is still debate today about the number of forces fielded, but it is fairly certain that if many volunteers and mercenaries from Anghiari thinned the Florentine ranks, so did the inhabitants of Sansepolcro, replenishing the Milanese army, which nevertheless continued to be smaller. On June 29, the day of Saints Peter and Paul, Piccinino decided to attack the opposing contingent, even though it was a public holiday, which was certainly not usual in a society governed by chivalric values, hoping thus to achieve a surprise effect. But victory did not befall him, and at the end of the same day, the Milanese army gave up and beat a retreat.

As is well known, Leonardo came to translate through preparatory drawings, a monumental cartoon and a wall painting that soon failed, only the central group of a scene that instead should have occupied many meters. This is the episode of the “Dispute of the Standard,” which we can only reconstruct through his studies and several replicas that have come down to us over time. What has struck the imagination of the artist’s contemporaries and even posterity is the fury and excitement that he managed to give to the fighting group. Indeed, the formation composed of four mounted leaders and three foot soldiers proposes a frenzied melee, where the horsemen are fused with their horses, like monstrous centaurs. Every face and body is deformed in an almost grotesque manner, as if to heighten the drama of the war, so much so that even the horses themselves participate, biting each other. Although there are somewhat conflicting opinions, in the truth of the unfolding of the battle it is quite likely that the clash was much less fierce and bloody than Leonardo let on, perhaps in a desire to emphasize a war he blamed or perhaps, more easily, as a result of a request from the commissioners, who wanted to give greater emphasis to the heroic effort of the Florentine army.

Nonetheless, the clash was not resolved even with a single death, as Niccolò Machiavelli, always ready to mock the warlike events moved by mercenaries, would like to imply: “And in so great a rout and in so long a tussle that lasted from twenty to twenty-four hours, there died but one man, who not of wounds nor of any other virtuous blow, but fell from his horse and trampled to death.”

In order to immerse oneself in the places of those events that were fought just outside the walls of the charming village of Anghiari, it would be proper to start from the Museum of the Battle, which is located in the historic center and thanks to which it is possible to learn in detail about the battle through an evocative diorama and much other material between an in-depth study of Leonardo’s work through some well-known printed replicas. But Anghiari itself also smells of these exploits, a land of soldiers of fortune, many who became revered condottieri, of whom the sumptuous palaces they had built remain as evidence, and just in front of the previously mentioned museum is the Museum of Palazzo Taglieschi, now the Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions of the Upper Tiber Valley, but once the residence of important professional soldiers. But there are many condottieri born in these lands who also link their names to the local toponymy, such as Baldo di Piero Bruni, known as Baldaccio d’Anghiari.

Returning to the traces of the battle, it is said that, where today stands the sumptuous Theater of the Academy of the Ricomposti in late Baroque style, Attendolo encamped here saw the Visconti army’s offensive, thanks to the dust raised by the cavalry in the valley below, and thus nullified the surprise effect by sounding the alarm and launching himself to meet the enemy.

Leaving the Porta Sant’Angelo behind, and skirting the mighty walls of Anghiari, one travels along the dizzyingly straight artery, renamed Via della Battaglia, which has connected the village with Sansepolcro since the 14th century. Here in the distance the Milanese troops moved. One will encounter the very ancient church of Santo Stefano, a building with characters of Byzantine-Ravenna influence, which stands outside the city walls at the beginning of the plain that reaches Sansepolcro, and has some splendid elements, such as the columns with perusal Ionic capitals. And although there is a lack of evidence of this, we can imagine that in a religious era such as the one we are talking about, some soldier would retire in prayer in this sacred place.

From here we can admire the splendid town of Anghiari perched on the high ground from which it dominates the plain. In the countryside that still resists little urbanization and is colored with the changing seasons, there must have been the many tents of the coalition, calling to mind the one painted by Piero della Francesca in nearby Monterchi, which encloses the Madonna del Parto.

Continuing along the narrow street, one encounters the chapel known as the Maestà di Santa Maria or Chapel of Santa Maria della Vittoria, which was in fact built in 1441 as a perpetual reminder of the defeat inflicted on the Milanese. It was in this very area that the battle was fought, also played out in part on a stone bridge, no longer extant, that spanned the Reglia ditch, or Reglia dei Mulini, where Attendolo was able to slow down the Milanese army so that the allies could rally their forces. This canal was built in the 13th century, diverting the waters of the nearby Tiber, so that it could irrigate the surrounding area and feed the mills.

The bridge, as indeed the whole battle scene, is eternalized in that splendid testimony to the period that is the caisson in the National Gallery in Dublin, where on one side is vividly depicted in tempera the Battle of Anghiari.

The Florentine Republic was magnanimous with Anghiari, and to celebrate the town’s contribution, it wanted to exempt its citizens from paying certain taxes for the duration of ten years. In addition, for the occasion it was decreed that a contested race, the Palio della Vittoria, could be held every June 29, which in time was transformed into a horse race and then suppressed due to the occurrence of some bloody riots in 1827. Since 2003 it has been reinstated again and is run each year on foot from the Chapel of Santa Maria della Vittoria to Anghiari’s Piazza Mercatale.

This is “an example of what we try to call context: that vortex of past and future, of knowledge and beauty, of stories and encounters,” to use Tomaso Montanari’s words, “that indescribable set of nexuses and connections that is released when we decide, to see, to know and to love” down to the smallest fragment of our landscape and artistic heritage.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.