The art of stopping time: the portraits of Ugo Mulas

Since time immemorial, in human history, hands have made themselves eternal protagonists, ancient and irreplaceable tools that shape, transform, create and destroy by the mere force of gesture. In the photographic workshop of Ugo Mulas, these very skilled tools, etched by subtle traces of experience, perform a ritual of visual alchemy that unravels in the silence of the darkroom and, far from the intrusive light of day, become the epicenter of every action, the silent guide of a process that converts the image into tangible and eternal memory. Every crease, every wrinkle, every imperfection tells stories of assiduously reiterated gestures, of precise and measured touches that bring the photographer’s vision to life by dancing in balance between chemistry and delicate shadows.

It is in the controlled darkness of this intimate space that one of Mulas’ many experiments takes shape as he brings to life, with analytical rigor, the seventh of his Verifications, The Laboratory, dedicated to Sir John Frederick William Herschel, the discoverer of sodium hyposulfite used for fixing images. “It is my verification of the laboratory,” Mulas writes, “an operation in which the camera is excluded and the development and fixing are emphasized: an operation that I wanted devoid of all emotion and extreme dryness and clarity, such as can be grasped in the scientific note left to us by Herschel.” In these words lies the pure essence of photographic practice, devoid of emotion and unnecessary frills, abandoned naked in its extreme precision, but giving us a precise and lucid portrait of the artist.

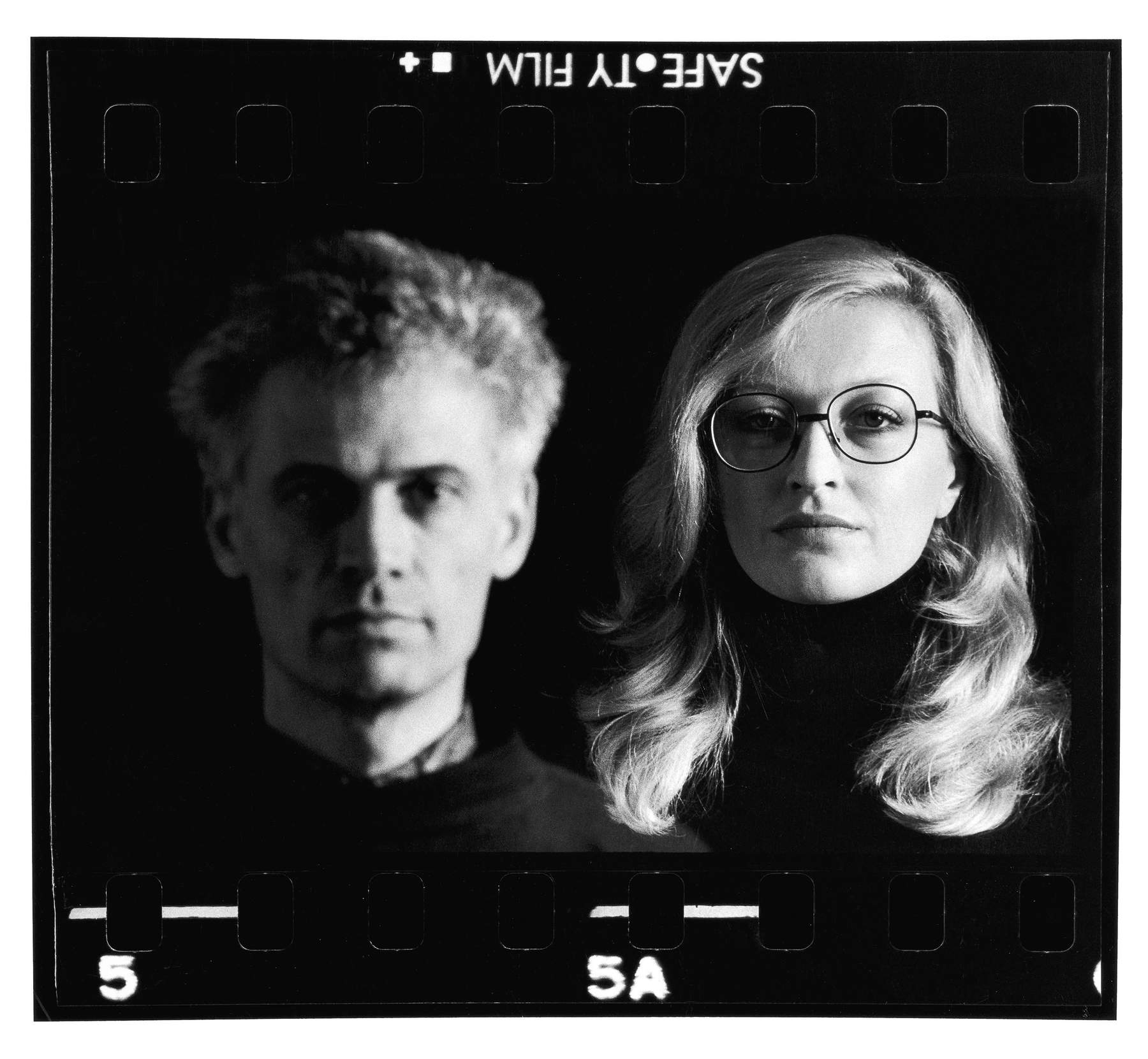

Mulas, in the coldness of this never-made shot, tells about himself even better than in any other self-portrait: he tells of a man estranged from himself, who never sees himself, but who looks at the world with an insatiable need to understand it. And, thus, in his workshop everything is accomplished with his hands: they lift the sheets by letting them take light, place them under the enlarger, adjust the focus with calculated movements, plunge them into developing and then fixing. There is no camera to guide this operation, and only the hands are the real protagonists tracing the imprint of the image on the sheet, and “that is why, in a pair of photographs, I wanted to make them a single subject: one hand immersed in development, the other in fixing, to divide the sheet into two hemispheres, each in its own stage of creation. The hand involved in the development appears immediately, in clear definition; the other emerges only later, when fixing makes the white half eternal and the dark half immutable.”

In 1970, Ugo Mulas was diagnosed with an illness that would lead to his death in just three years, and this event became only the first fuse that led him to quickly conduct a profound reflection on a path that had already been started but never brought to full fruition. The photographer, abandoning the work of documentation, devoted himself to the creation of autonomous works that culminated in the famous Verifications series. In this extreme research, each shot is an intimate investigation into the very nature of photography: here, the object is placed in direct contact with the negative, and the stages of development are reduced to the essential, stripped of all artifice. For Mulas, a self-taught artist with long experience, this turns out to be an urgent need for clarity in order to arrive at an objective truth, which results in a reflection on the photographic gesture as a pure act. Thus, in Verifiche (Verifications), each shot is freed from its mere documentary function to become an object of autonomous research, where elements such as the negative, the sensitive surface and the act of development are elevated to symbols of a poetic but authentic reality.

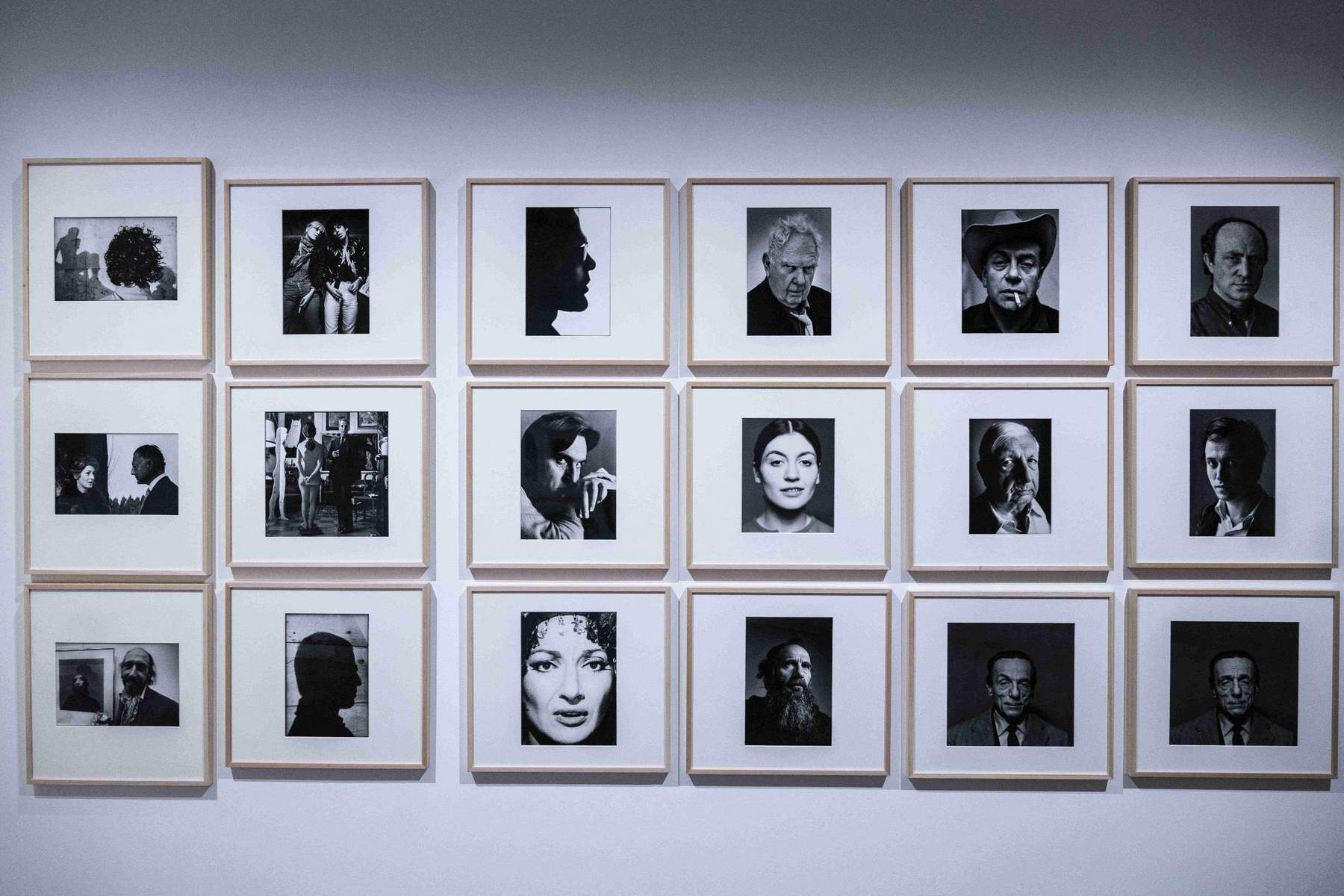

Part of such a series are The Photographic Operation. Self-Portrait for Lee Friedlanderand Self-Portrait with Nini. To Melina and Valentina (exhibited along with many other portraits, until Feb. 2, 2025, at the exhibition Ugo Mulas. The Photographic Operation at the Royal Palace in Milan). In the first work, the photographer shows himself, or rather his camera, to the viewer no longer as an impartial narrator, but as a storyteller of reality. He stands before a window where a mirror is placed; the sunlight creates the shadow of a pillar on the wall, and, at the same time, also projects the darkness created by the artist’s own body. The camera covers his face, concealing his features and turning into a tribute to the one who, more than any other, perceived the problem of the machine as a barrier, and tried to overcome that limit that the medium itself imposes in the process of knowledge and creation: Lee Friedlander. “Perhaps,” Mulas says, “here as in the later self-portrait with Nini, there is an obsession with being present, with seeing myself as I see, with participating, involving myself. Or, rather, it is an awareness that the machine does not belong to me, it is an added medium whose significance can neither be overestimated nor underestimated, but precisely for this reason a medium that excludes me while the more I am present.”

We will never know with certainty whether this incessant need to be there, becoming a spectator and voyeur of himself, hides the fear of an already written and imminent death; yet, it seems clear the will to give life to authentic works of art, which overcome the typical torment of the photographer and open up to extremely lucid thoughts, immersed in an intense haze and in the feverish urgency of creating. Thus, as a blurry and inaccessible face, simultaneously absent and present is represented inSelf-Portrait with Nini, in which his wife stands out brightly from the blackness that surrounds her while the photographer, in that darkness, seems to be totally immersed without any will to emerge. “She is in focus because I was the one photographing her, that’s how I saw her and that’s how I wanted to see her, because I always want to see with maximum clarity what is in front of me, and to photograph is to see and to want to see, first of all”, Mulas says with that forever smoky face, “because there is only one part of the sensible world that man, who can see himself as he looks, according to Merleau-Ponty, cannot see of himself: the face.” To that conundrum, the individual can only respond with fragmentary images: the memory of other photographs, the reflection in a mirror, some random detail, but it remains elusive, like a subtle shadow, a presence that he can never fully grasp and that is the self-image. Even the moment the photographer leaves the camera to stand on the other side of the lens, that reality does not change, for he continues to be unable to grasp himself entirely. When he adjusts the focus, everything in front of him appears perfectly sharp, he owns the world and understands it, but his face remains absent, as if to show that the act of knowing and looking at himself is by nature constantly incomplete.

Exactly like the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Mulas explores the indissoluble entanglement between seeing and being seen, between the body and the world. And while the Frenchman elaborates the concept of “flesh” to define the continuity between the percipient and the perceived, Mulas, through his Verifications series, seeks to unveil the essence of the photographic medium as a unique act of existence and vision. Merleau-Ponty very strongly questions the idea of the physical world as an objective, fixed reality and emphasizes how the original perception of each individual always remains fluid and never traceable to cold Cartesian rationality understood as res extensa, as distinct from res cogitans. He describes how, every time he blinks or moves his eyes, the world seems to change slightly, attributing such very rapid changes to himself rather than to the observed objects and suggesting a perpetual connection between perceived and percipient, without a foreign filter between the body and reality. The world and the subject, in Merleau-Ponty’s thought, as well as in the works of Mulas himself, remains intimately and inextricably intertwined in the “bond of the flesh,” highlighting how the body is part of the world and the point of intersection between the visible and the felt, and how all perception is inseparable from corporeality. And it is precisely because of this lack of clear separation between self and other, between inside and outside, that in the photographer’s works a relationship is constantly created that integrates proximity and difference, as happens with the very famous portraits to artists and the life that flows between the tables of the Jamaica bar in Milan.

The photographer always finds himself creating “pieces of memory” giving his images a perpetual sense of stillness, as in them living is transformed into absolute and rarefied stillness. Thus he becomes a critic and interpreter of the art of his time, succeeding in explaining, with full clarity, who all those artists are hidden behind their works.

Always driven to immortalize the banality of life, he portrays now Piero Manzoni at the bar in Brera in 1953, now the writer Luciano Bianciardi and the photographer Carlo Bavagnoli in a small bedroom, intent on discovering the photographer’s ill-concealed presence, and finally a Joan Miró in 1963 next to Pollaiolo’s famous Portrait of a Young Lady exhibited at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum. “When you take a portrait of a person,” Mulas reveals, “you can take an infinite number of attitudes toward the photographer. There is no more portrait than the one where the person stands there, posing, aware of the camera, this toward the photographer, as if to deceive them, to say: I am here, but I pretend not to know that you are there, so my fiction will be more believable.”

Photography, then, is not just a document, but must be a key to understanding, an act of understanding the world where the photographer’s task is to convey through the lens what he perceives, trying to decipher the work in a single shot. In this sense, Duchamp’s portraits are not merely portraits, but are meant to make visible his mental attitude toward art, that approach manifested in a silent rejection of the making of an artist who conscientiously chooses silence as a form of expression, who rejects the concept of incessant production, transforming his silence into a new form of creation. Photographing such a subject, then, becomes a contradiction since photography, by its very nature, implies an act of existence that Duchamp, with his detachment, rejects. Therefore, Mulas, prefers to capture him walking, since walking represents the very essence of life, a primordial act, free from the need to produce and capable of expressing the very essence of existing.

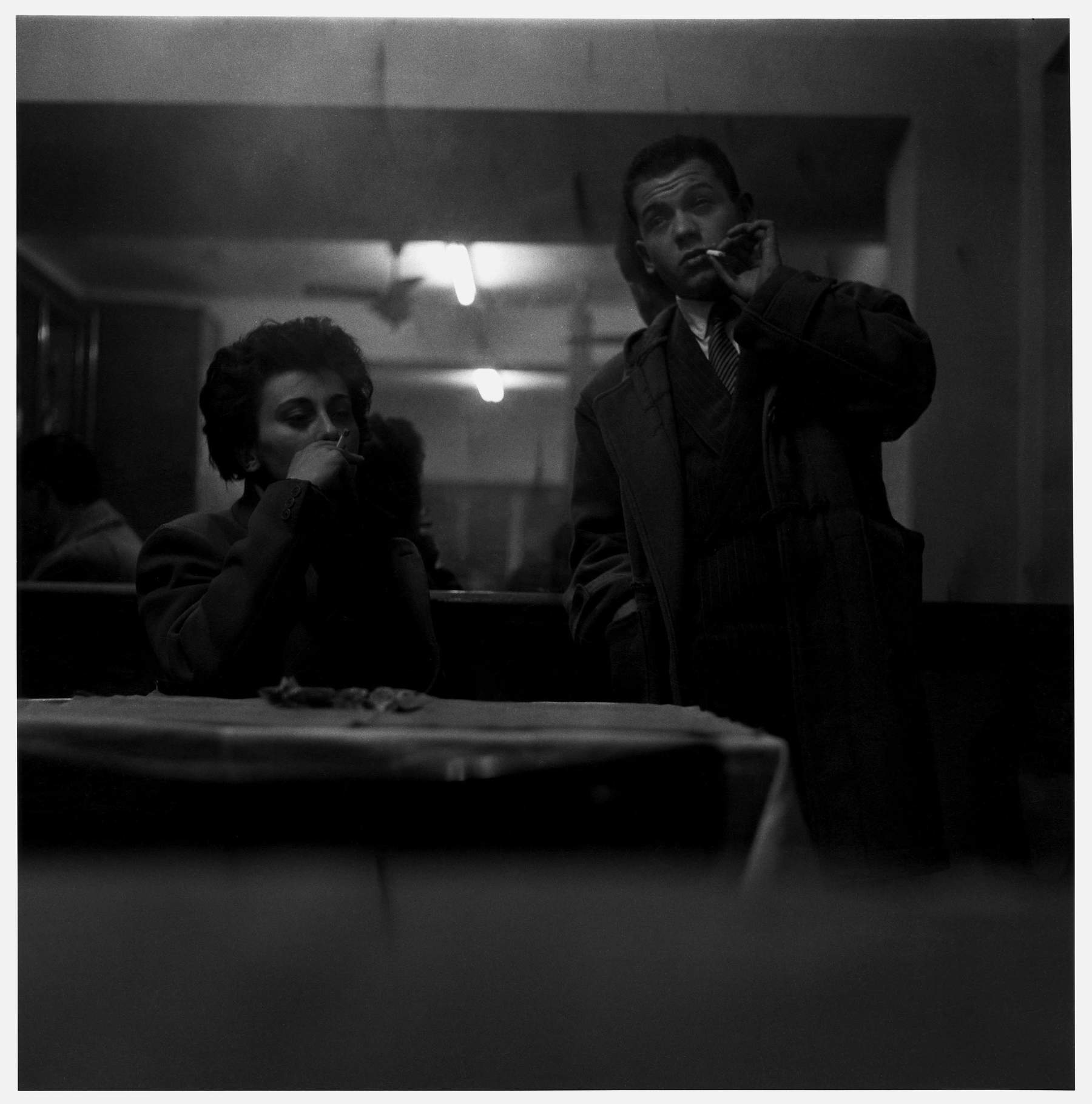

Among the most iconic shots is that of an elderly Duchamp, sitting at a concrete table in Washington Square, in front of a chessboard with no pieces. Duchamp does not even look at it: it becomes a symbol, a sign that transcends its usual context, struck by the light that illuminates a face that is serene but aware of the photographer’s presence. In these shots, Mulas seems to want to capture the nature of the artist, who observes his own existence from afar, more spectator than actor, as if to demonstrate that indifference to doing.

When he photographs him visiting the MoMA in New York, among his own works, Duchamp appears as a man out of time, suspended in a bridge between past and present, and those creations, which once belonged to him, now seem to be no longer his: Duchamp observes from afar, as if he had become part of the art he helped define.

In New York, Mulas, set out alone, with a desire to understand and witness by penetrating the studios without knowing the language, barely communicating, trying not to disturb, not to get in the way of the artists’ work. Each shot for him represented an opportunity to discover something deeper, to avoid that usual formal portrait in order to seek a more authentic view of the character: his intention was to grasp the link between the artist and his creation, trying to intuit what gesture or attitude was crucial in the process leading to the final result of the work. In Newman’s case, for example, the photographer realized that portraying him while he was painting would not be sufficiently revealing, since what struck him most was the ritual that preceded his painting: that meticulous order with which he prepared the studio and his fatherly way of protecting the canvas from the residue of color. Even the simplest and most mundane of gestures speaks of a rigorous and careful personality, from the elegance of his clothing to the precision of his movements.

Totally different is the actions of Andy Warhol, who from Mulas’ accounts “always seems to be doing nothing” in that studio of his where chaos reigns and in which the eccentric artist “moves with an indifferent manner. Yet it is clear that everything revolves around him.” For the first time, this accepting attitude, open to every proposal and ready to be manipulated, puts in the balance every certainty of the photographer who discovers himself trapped in the millions of possibilities. So, initially intimidated, he takes courage and uses the artist as a mannequin by first placing him in the midst of the Flowers series scattered in bulk in the Factory, then in front of a large mirror where the protagonist seems to be more the photographer himself than the subject to be represented. After all, art, like photography, has now become something different that does not refer only to the surface in which it is fixed, but appropriates mental and gestural spaces, renouncing a traditionally imposed form: it is the gesture that produces the work, and it is precisely those constellations of movements that Mulas forever imprints in history, creating sharp portraits of artists such as Fontana, Calder, Burri and many others.

Lucio Fontana’s portraits present us with evidence of a gesture that Mulas felt needed to be understood. What to a less attentive audience might seem like a quick, absent-minded cut on a canvas instead reveals the personality of a man who waits, sometimes weeks at a time, before opening the surface. It reveals the story of a man who fails to give away that action so intimate and personal to the eyes of his photographer friend, who is forced to create a calculated staging of it. “If you film me making a picture of holes,” Fontana reveals to the photographer, “after a while I don’t feel your presence anymore and my work proceeds quietly, but I couldn’t make one of these big cuts while someone is moving around me. I feel that if I make a cut, just like that, just to take the picture, it definitely won’t come ... maybe, it might even succeed, but I don’t feel like doing this in the presence of a photographer, or anyone else. I need a lot of concentration. I mean, it’s not like I go into the studio, take off my jacket, and trac!, make three or four cuts. No, sometimes, the canvas, I leave it hanging there for weeks before I’m sure what I’m going to do with it, and only when I feel sure, I leave, and it’s rare that I waste a canvas; I really have to feel fit to do these things.” Mulas then convinces Fontana to pretend to make cuts, and so the two of them place a new canvas on the wall, and “Lucio acted as when he is waiting to make a cut, with his stanley in his hand, leaning against the canvas, high up as if the work began at that moment: you see him with his back turned, you see a canvas where there is nothing yet, there is only a canvas and him in the attitude of someone who begins to work on it. It is the moment when the cutting has not yet begun and the conceptual elaboration is instead already all made clear.” Only after that first photo, in which Fontana observes the canvas in religious silence, and that staging of a cut that never happened, does Mulas understand with incontrovertible certainty how concentration, care, and waiting for the right moment defined the true meaning of his cuts, the Waiting. Soon after, they replace the blank canvas with a finished painting marked by a single large cut. Fontana places his hand at the terminal point of the cut, and, in one of the photos, Fontana’s hand is moved, “as if he had just at that moment completed the stroke: you can’t tell that that photo was specially created,” in which the cut already exists before the photograph.

This is the great game of art: telling without ever fully revealing all those subtle textures that are secretly hidden between the folds of a canvas. In a 1968 portrait, also of Lucio Fontana, the photographer creates a trace of his own biography by using a very close-up on the artist’s large right eye, which becomes a universe embedded in his time-scarred face, a horizon in which the chapters of his life are read and each line turns out to be the perfect sum of all expectations. In the deep blackness of that eye, the photographer appears as a reflected shadow, a visitor in an intimate and secret dimension, imprisoned in that well of past memories, as if the old eye had absorbed him for an eternal instant, holding him in limbo in a perpetual struggle between past and present. Photography, on the other hand, for Mulas lives in a suspended time and succeeds, more than any other art, in fixing and prolonging a gesture, a memory, a glance indefinitely, creating a motionless but never linear instant. An action that, as essayist Roland Barthes points out in The Clear Room, makes one think of death since the person being photographed “is no longer a subject nor an object, but rather a subject who feels himself becoming an object.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.