The art of Leonor Fini, sorceress and female icon

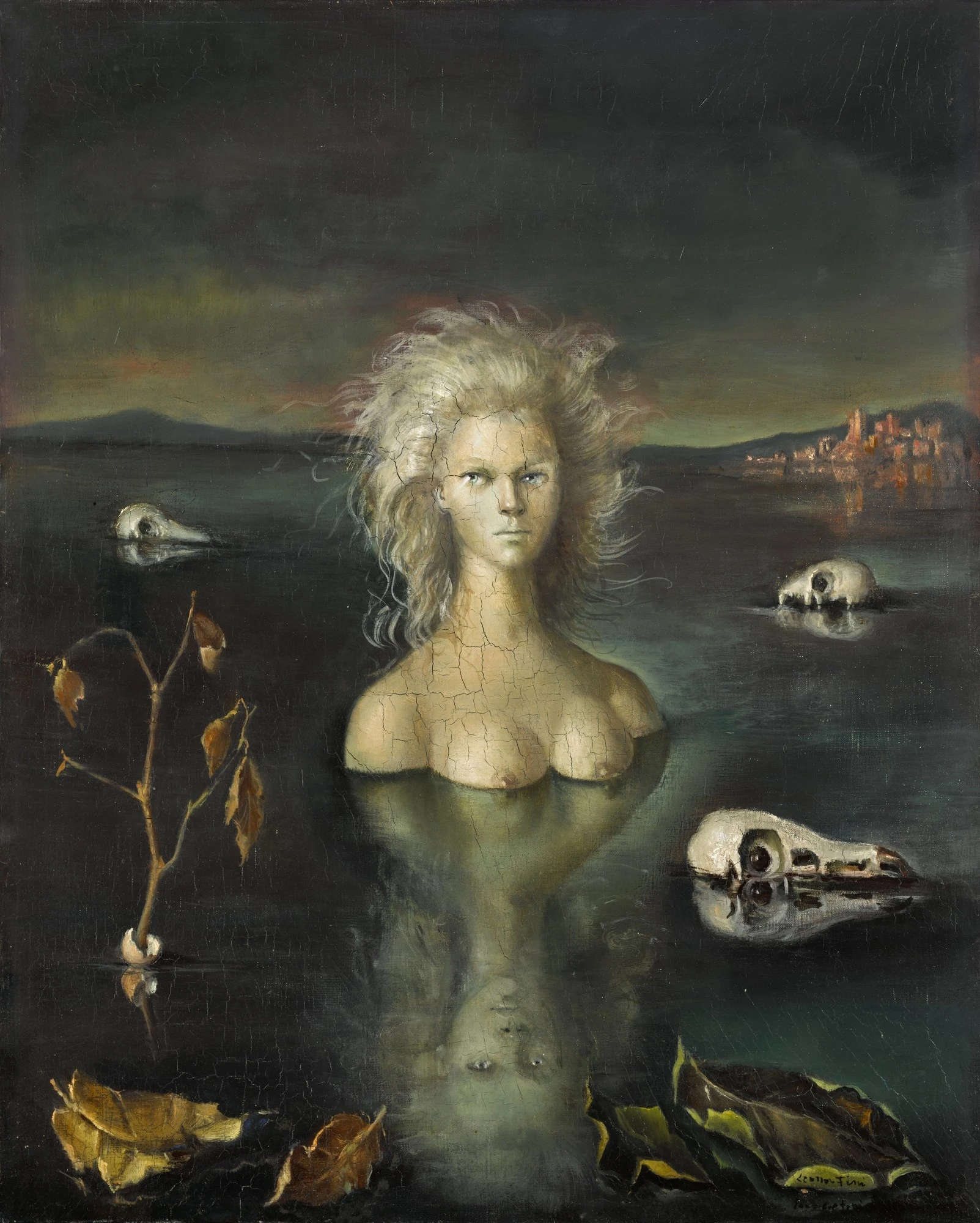

Sorceress, shaman, female icon, Leonor Fini (Buenos Aires, 1907 - Paris, 1996), with her seductive and disturbing works, has “frightened” respecters of all ages, reopening questions that remain unresolved even today. An unclassifiable woman and artist, she has always been talked about in contradictory ways, sometimes leaving a bitter taste in the mouth about the scope of her work and her eventful biography. Diverse and unquestionable, however, are her artistic gifts, from performance and painting to theatrical and playful disguise, and they are to this day the demonstration of a talent that needed to be understood even by herself in order to be able to explore, free, all possible languages to define a strictly personal worldview. Gifts not unlike those of haruspices or “guardians of the threshold,” capable of recovering forgotten and repressed original forces, arcane and obscure that refer back to the archetype of the Great Mother: a whole magical, imaginative universe that, in the end, became for Leonor a powerful “healing” rite, an invisible bridge between the dimension of reality and the spiritual dimension.

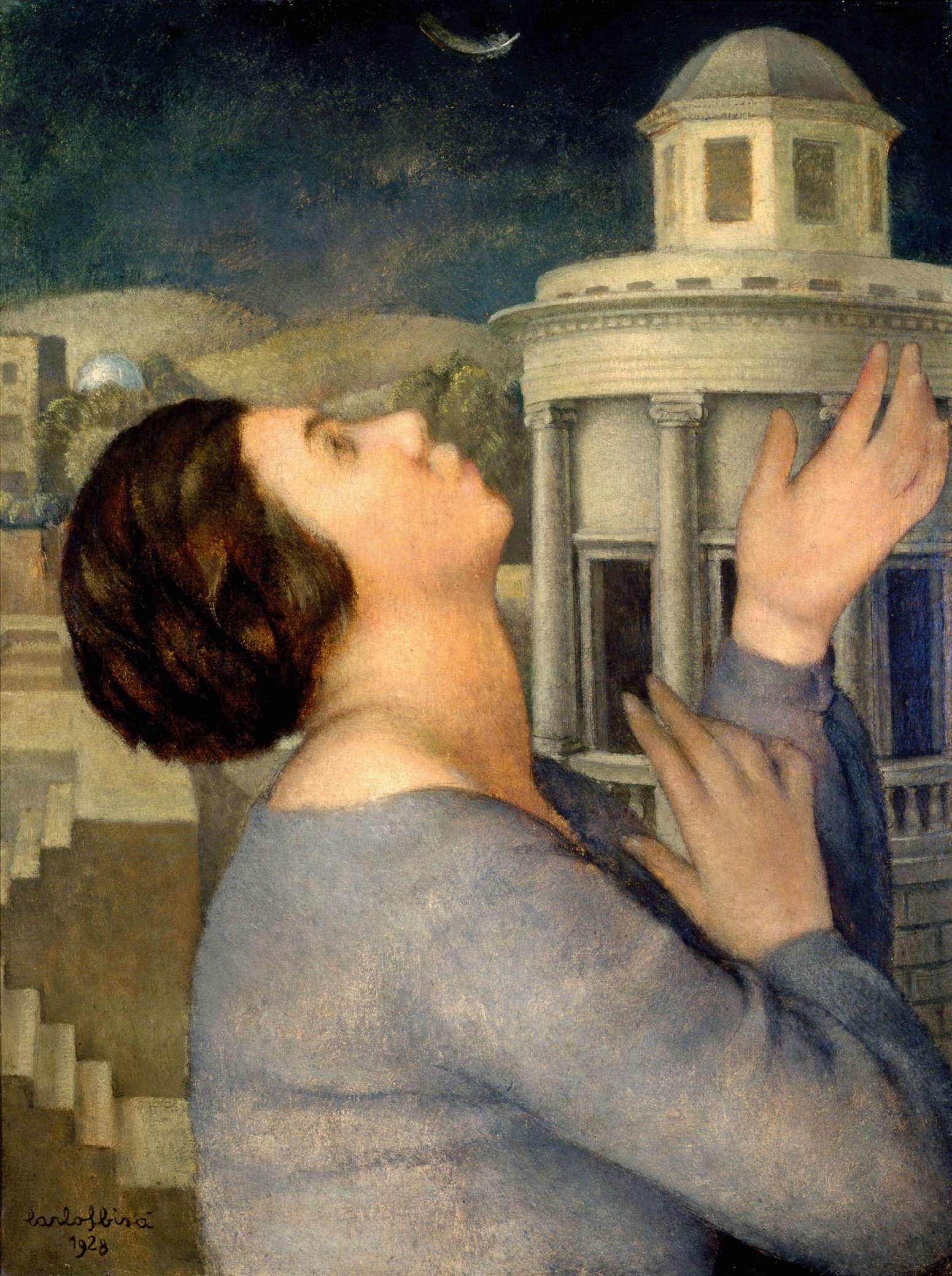

After all, one of the works that best pays homage to this fabulous nature of hers was created by Carlo Sbisà in 1928: Magia or Portrait of Leonor Fini . These invisible, feminine energies, Leonor Fini was able to stir them up brilliantly in her vast artistic production that began in the 1930s. Her biography and the characteristics of her temperament also concur to support the hypothesis of the shamanic force of her art: initiation, displacement, her essence as an outsider, and the misunderstanding of her work.

The initiation into her journey, in fact, begins from an early age, from the time when two “accidents,” with antithetical meanings, force her to look at the world with different eyes: the stumbling into the two male figures of her father and uncle. But compared to the “creative” and prolific presence of her maternal uncle (the lawyer and educated Ernesto), from the “long shadow” of an abusive and persecutory father, it will soon be her mother, Malvina Braun, who saves her with an original stratagem: the disguise as a male, since, since she is a child, she returns with her to the Central European city of Trieste. Leonor will take on disguise as a connotation of her artistic practice. A trait that will also mark her work with the work Voleur d’enfant, which traces, albeit with the delicacy of her early painting, her father’s attempts to kidnap her.

Many elements reinforce this shamanic attitude in her way of making art, which, moreover, allows her to “live her earthly existence in a continuous rituality consisting of elements related to representation,” the same with which Fini approaches her work. In addition to her constant travels-between Trieste (where she met Arturo Nathan, Gillo Dorfles, Umberto Saba, Italo Svevo), Milan (here she frequented the artists of the Novecento group), Paris (where she met in particular Elsa Schiaparelli and Max Ernst, who became her lover), Monte Carlo (fleeing in 1940 from theGerman occupation of Paris, where she met Stanislao Lepri, an Italian diplomat with whom she began a romantic relationship that she, together with Constantin Jelenski, a Polish writer, would love for the rest of her life) and finally Rome (from 1943, a city where she will forge important friendships with Anna Magnani, Elsa Morante, Mario Praz, Carlo Levi, and Luchino Visconti); signs of her particular charisma are her being anindefatigable outsider (despite frequenting almost all the avant-gardes of the century); and the insistent misunderstanding of her art, never quite recognized, indeed, sometimes debased, downplayed, because it was the expression of a feminine universe, therefore mysterious and indecipherable.

Then there is another factor to consider; the long, difficult and never-ending struggle to achieve women’s emancipation began around the years in which Fini appeared on the art scene. Although, in fact, many rights (work, gender equality, reproductive autonomy, and the right to the termination of pregnancy) were acquired for women in the twentieth century, in light of the controversial consideration of thework of Leonor Fini and with respect to an obvious regression of the current female condition and imaginary, it is questionable how real those “conquests” had been, or if nothing else, how preponderant their impact in society really was. Borrowing the Finnian affair, it is therefore necessary to reconsider the gaze with which her work was viewed.

If it is true, as Rosa Luxemburg wanted, that calling a spade a spade is a revolutionary gesture, it is also true that very specific names have defined the optics with which Fini and many other women artists have been evaluated: bourgeois respectability, tired patriarchy and extreme narrow-mindedness. Paying a price is necessary for advancement in the process of evolution, but the highest price is mostly paid by women, and Leonor Fini has not been outdone. With the exception, in fact, of an exhibition scheduled for 2025 at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, there has never so far been thought of a major solo exhibition that would consecrate even today and once and for all her artistic value through a careful study of her production. This is an inexplicable lack, since Fini was not only a formidable and all-round artist, painter, costume designer, illustrator, writer and performer, but in her lifetime she achieved many successes and exhibited in all the most important cities of art. So what has brought about this devaluation now? Is it a renewed macho ostracism?

Are we forgetting that her artistic “genius” rang whatever chord it touched, whether it was the strings of a trend of the period or an avant-garde, the techniques and themes of Surrealism or the language of Informal and Pop Art; because in her continuous artistic endeavors, Leonor Fini absorbed all the novelties of the 20th century, entering and leaving a group, advancing and retracting their theses. Fini dropped out each time, not only because she was hostile to artistic customs and consortia but nonetheless, because in none of those groups could she openly explode her creative personality as a magician, inventor of parallel, transfigured and irrational worlds.

Although “there was no other movement, apart from the specifically feminist ones, in which there was such a high proportion of active and participating women” (so Alessandra Scappini), it was mainly with the Surrealists and in particular with Bréton’s positions that she ended because in their imagery, women were to be limited to being muses and objects of desire, or, at most, were seen as sorceresses, seers, but in a negative sense, that is, as those who privilege the unconscious and irrational side, at the expense of the “more just” male rationality. “An ideal far removed from ours, closer [...] to recognize herself as seer, seeker in the existential path” (Scappini), and protector, if anything, of a “pan-erotic” universe, “winking” and constantly in search of a changing identity. In her artistic and expressive quest, Leonor has never forgotten, as in a “kaleidoscope of reflected icons,” even the pictorial tradition. Indeed, among her paintings, the sign of antiquity and neo-Platonic culture runs subtly: Van Eyck and Cranach, the Pre-Raphaelites, de Roberti or Piero di Cosimo, Arcimboldi, and these references, sometimes very close to the interests of surrealism, will be almost a constant and often, Alessandra Scappini always argues, “implemented mainly through the strategy of mimicry and metamorphosis of scripture.”

In her lifelong creative and alchemical experiment, Leonor Fini mutated herself and her painting several times. The plastic treatment of her early days (as in the Portrait of Judge Alberti, 1927) that was also Achille Funi ’s teaching was transformed into something very different when, in 1931, she arrived in Paris. There, his language is measured against the great foreigners and makes his palette clearer, his outlines softer. It was in this experience that she began that exploration of the dark sides of femininity that was to become a common thread in her future work and that would result in the use of animalia, especially sphinxes as in the work Sphinx Régine.

But this is not how her career ends because after Paris it is America’s turn. He will exhibit with Max Ernst at the Julien Levy Gallery and at the Museum of Modern Art with Salvador Dalí and Giorgio De Chirico. And after that again Rome. Where he arrives following Lepri. At this juncture he will also devote himself to universal themes such as the relationship between life and death, and it is then that he makes works such as Bout du monde and L’ange de l’anatomie.

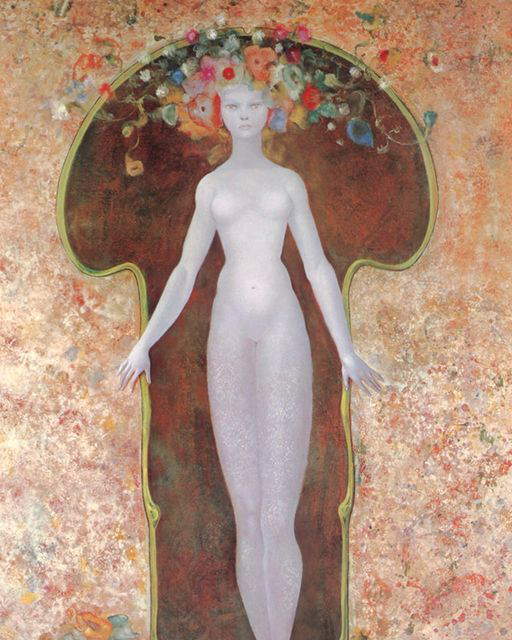

From the 1960s his palette rediscovers light with dreamlike works where the female presence almost completely dominates, of which La serrure and Le bagnanti are examples. Then something cracks, perhaps the death of her mother, Lepri and Jelenski will again obscure her vision. “I see in them something restrained, immobilized, theatrical still images that impose themselves on me, theatrical sometimes myself.” She died at the age of 89 in 1996.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.