We owe to a critical journey begun in the 1970s, preceded by an isolated and pioneering contribution by Emma Calabi in 1935, the rediscovery of a sensitive, fascinating and singular painter like Giuseppe Zola (Brescia, 1672 - Ferrara, 1743), one of the great masters of landscape painting of his time. The first critical reconnaissance bears the signature of an important art historian, Eugenio Riccomini, who focused on the artist in 1971 on the occasion of an exhibition he curated that year in Bologna(Il Settecento a Ferrara), which was followed by further chapters in other important reviews, such as that of 1979 dedicated to eighteenth-century painting in Emilia, to arrive, in 2001, at the first monographic exhibition curated by Berenice Giovannucci Vigi, based on the nucleus of Zola’s works coming from the Monte di Pietà in Ferrara, then owned by the Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara and now, after the merger of the Ferrara credit institution with BPER Banca, merged into the collections of the Modena institution. The most recent chapter in this rediscovery, exactly fifty years after Riccomini’s report, is the exhibition Paesi vaghissimi. Giuseppe Zola and Landscape Painting, curated by Lucia Peruzzi (December 10, 2021 to March 13, 2022 at the BPER Banca Gallery in Modena), a dossier exhibition focused on eight canvases from the BPER collection, which with thirty-two paintings by Zola holds the largest existing nucleus of paintings by the artist from Brescia by birth but Ferrara by adoption.

A very prolific painter, Giuseppe Zola, although little known today, was highly esteemed in his lifetime and was also held in high esteem by critics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: suffice it to say that Luigi Lanzi included him in his Storia pittorica dell’Italia, pointing to him as one of the architects of the rebirth of the “art of making villages,” or landscape painting, in eighteenth-century Ferrara. We do not know how Zola came from Brescia to Ferrara, nor when: the artist’s biography still has several gaps to fill. What is certain is, writes Lucia Peruzzi in the catalog of the BPER Banca Gallery exhibition, that “the masters of the local tradition could not help him in any way in inspiring his waterfalls, fords, ravines, and leafy trees that he manages to square a bit everywhere in the city’s palaces.” Zola may have consolidated his training and honed his sensitivity to nature, of which he was one of the finest interpreters in the eighteenth century, by studying in Venice where, in the latter part of the seventeenth century, one of the leading “paesisti” of the time, the Dutchman Pieter Mulier known as Cavalier Tempesta, and the Austrian Johann Anton Eismann, who, according to Riccomini, was perhaps even more important for the young Zola’s training, were active. Both Cavalier Tempesta and Eismann may have decisively enriched Zola’s cultural background, the former for the serene and Arcadian character of his landscapes as well as his atmospheric effects, and the latter for his ability to punctuate landscapes with presences (castles, ruins, harbors) likely to increase their scenic impact. And then, other suggestions surely came from the prints to which Zola surely had access.

In his paintings, Zola tried his hand at a wide variety of landscapes: views of idyllic countryside, seascapes with busy harbors, cliffs in the mountains, intricate forests, waterfalls. All, however, are characterized by a search for effect, unpredictability, and attention to detail, in a style that, Lucia Peruzzi wrote, is "easy and appealing, moderately rocaille, luminous in color and elegant in workmanship,“ and that was highly appreciated by his contemporaries. These are themes that met eighteenth-century taste, which was more inclined to lose itself in an animated and picturesque nature than to contemplate a balanced and harmonious nature. Zola’s is, for Peruzzi, a ”limpid and clear nature, fantastic yet everyday, where the eye flows over accurately described details in the calm spread of light." An interesting example of this poetics is one of the paintings considered to be Zola’s finest, the Port Scene with Ruins, which the erudite Cesare Barotti, in his publication Pitture e scoltore che si trovano nelle chiese, luoghi pubblici, e sobborghi della città di Ferrara, recalled among the paintings placed from 1756 onward in the offices of Ferrara’s Monte di Pietà as decorations. It is a fanciful coastal view, with a few large trees guiding the viewer’s eye, an expedient this typical of Cavalier Tempesta (Zola’s landscapes are always carefully constructed): on the left, this kind of fjord is enclosed by a high cliff on which a small tree stands solitary. In the distance is a turreted hamlet on top of a hill, while in the foreground here is the beach, the small harbor where a few characters are bustling about, mooring a sailboat, and some derelict classical ruins over which thick vegetation has grown. In the foreground, two men and two women are conversing with each other in a “gallant encounter during a picnic,” as Giovannucci Vigi wrote in 2001. Instead, the sky is crisscrossed by white and gray clouds, as is typical of Zola’s paintings: a work that conveys calmness but that incurs debts to the “ruinist” painting of the Venetian Marco Ricci, and among the highest expressions of Zola’s art “for the very high quality of the painting, which does not omit every detail, evoking a view of fantasy, together with a piece of reality experienced in everyday life,” as Giovannucci Vigi wrote.

From the cycle that decorated the Monte di Pietà come other paintings now in the BPER collection, for example the River Landscape with Washerwomen and a Child and Landscape with Waterfall and Ruins whose tenor is not unlike that which informs the Port Scene. These are broad views, fading into the distance, dominated on the neighboring planes by large trees and with a few figurines on the lower edge that capture the viewer’s attention and are painted with a descriptive meticulousness reminiscent of Flemish landscapes: Riccomini, speaking of Landscape with Waterfall and Ruins, called to mind Herman van Swanewelt and Jan Both, Zola’s closest references in this painting where many of the typical elements of his poetics recur, summarized in the eighteenth century by the erudite Cesare Cittadella as follows: “now roads interrupted by stones, now streams and rivers and falling waters, now meadows and rustic factories, breaks of architecture covered with piles of ivy, cliffs, trunks and trees now green, now dry,” contrasted with “a torchy sky torn by lucid clouds.” The River Landscape is a work of Arcadian taste, centered on a country view, complete with a hamlet on the banks of a river crossed by an arched bridge, in which Zola also inserts some tasty bits of everyday life (the washerwomen in the foreground, the fishermen at work in the river) that transport us to a dimension of serenity and tranquility, in front of which, Lucia Peruzzi observes, even “the old rural hamlet on the left, with its familiar and reassuring solidity, seems to offer protection and refuge to an existence conducted far from the cares and artificial rhythms of society life.”

The countryside thus becomes locus amoenus where nature is happy and contented, where the passions that disrupt city life do not exist, where existence is characterized by simplicity and tranquility. However, Giuseppe Zola’s landscapes are distinguished from the views of classicist taste of the seventeenth century by the unexpected elements that aim to create effects, to evoke, and to some extent also to make evident, the contrast between wild nature and human beings living in nature, taming it but without forcing its rhythms and times: a tension already palpable in several of his views and anticipating the great landscape painting of the late eighteenth century, marked by the aesthetics of the picturesque (Zola’s, Giovannucci Vigi wrote again, is “a mediated reality, indeed [....] meditated on the virgin and wild vision of the models of the Neapolitan Salvator Rosa, on the picturesque and scenographic character of the iconographies of Antonio Francesco Peruzzini from Ancona, on the arboreal and tonal colorism of the Venetian Marco Ricci.”) Zola is, in fact, a resolutely modern artist from his beginnings, and these tendencies constantly permeate his art, despite the fact that he is a basically provincial painter, who after settling in Ferrara in the early eighteenth century never left the city again: he had, however, traveled extensively (it is speculated that he was banished for some reason from his hometown), and during his travels he had taken many opportunities to broaden his culture. The provincial dimension of his figure is one of two reasons for his lack of notoriety: the second is the fact that, given the character of his art, he worked mainly for private patrons, and consequently there were not many (and still are not) opportunities to see his works in public (although, Riccomini informed as early as the 1970s, an activity of his for public commissions, though marginal, is attested: for example, the frescoes in the Hall of Landscapes in the Castello Estense in Ferrara, works that are in any case difficult to judge because they have been retouched, could be his, or those of his circle).

Landscapes then also became the scene of episodes from religion, myth, and literature that became almost pretexts for splendid views. One of the highest examples in this sense is theGoing to Emmaus, which can be counted among the most beautiful paintings of Giuseppe Zola’s production: the episode, taken from the Gospel of Luke, lent itself well to being painted with a view, since Jesus meets on the road, near Emmaus, the two pilgrims who are on their way to Jerusalem, and the journey is the moment of the story depicted by Zola, with Jesus in the foreground, illuminated by the halo of his halo, accompanying the wayfarers to whom he will later reveal himself during the supper. Here, too, Zola mixes passages familiar to him (a glimpse of the Po Valley where we see a forest crossed by a dusty road that crosses a stream) with fictional elements, such as the rocky walls on the right, on top of which we see the usual village with towers and bell towers. “This canvas,” Peruzzi acknowledges, “is among the subtlest and happiest of the artist’s vast production, where the juxtaposition to Marco Ricci is most evident and overt.” the effects Zola seeks in this composition of “wide and restless breath” (the wind stirring the foliage of the trees, the rosy reflections of twilight light reverberating off the clouds in the distance, the steam forming near the little waterfalls, so much so that it almost seems as if one can hear the sound of water, the perspective that is lost in infinity beyond the horizon) are among the most evocative of all his painting.

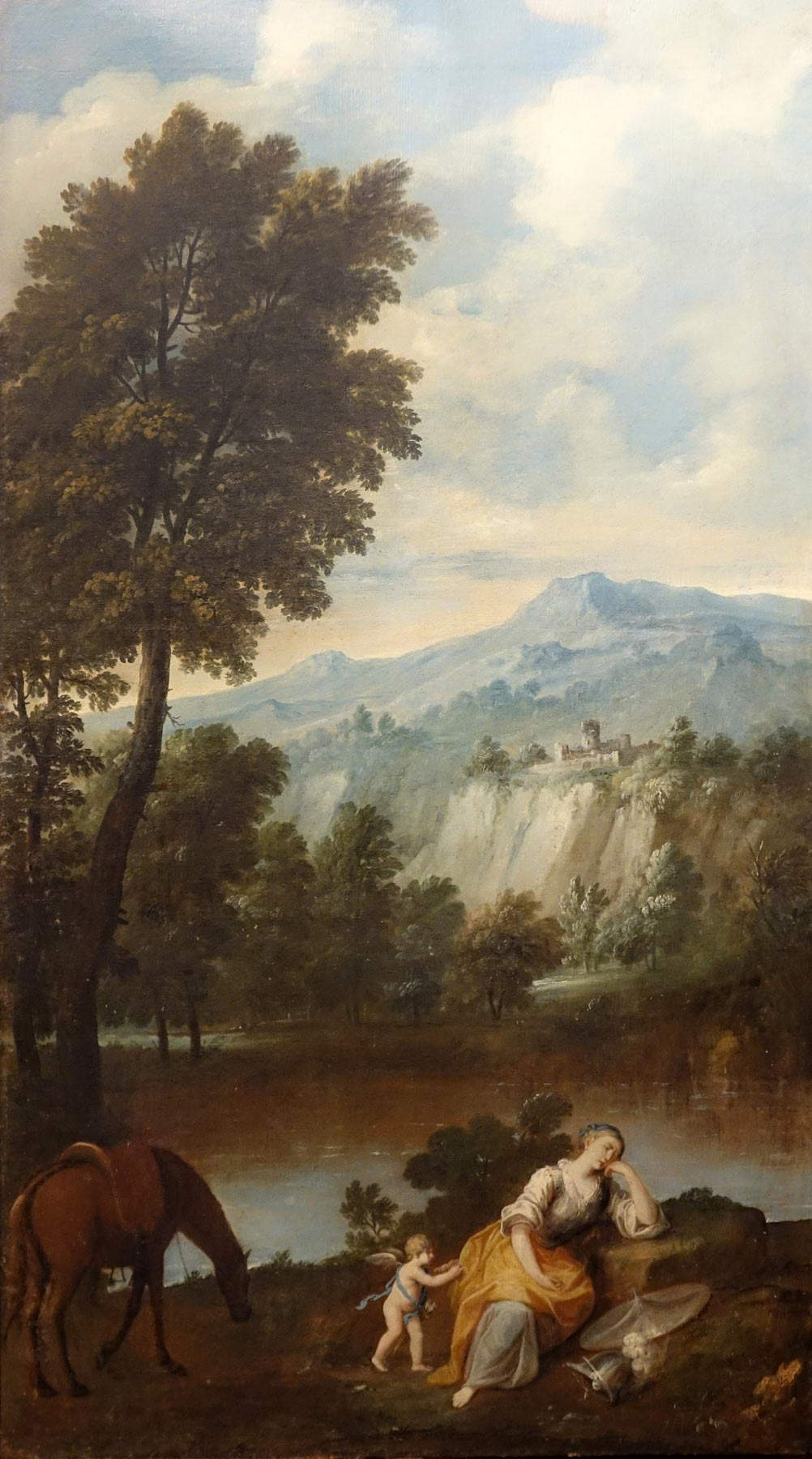

Zola being a Ferrara native in his own right, his art is not lacking in themes taken from Gerusalemme Liberata: in the BPER collection are preserved in particular a Rest of Erminia and an Erminia writing Tancredi’s name on the tree, vertical-format paintings that insert, in an Arcadian landscape with a Carraccian hint, the two episodes taken from Torquato Tasso’s poem. These are works of identical size that most likely originated in the context of a cycle dedicated to Gerusalemme Liberata: the view in this case, always enclosed on either side by a large tree, opens, as is often the case, onto a river enclosed on the horizon by a mountain, and the characters are arranged in the foreground. In the first scene, Erminia lies limply, and in a contrived pose, resting her elbow on a boulder, with a cupid pulling her by the robe to wake her up, while in the second she is caught again with the cupid helping her to write Tancredi’s name on the bark of the plant (both moments refer to Canto VII of Tasso’s poem). In this case, the countryside again becomes locus amoenus, and Giuseppe Zola’s reference, as mentioned, would seem to be Annibale Carracci rather than the aforementioned Salvator Rosa, partly because of the very balanced character of the landscape that frames it in Giuseppe Zola’s so-called “first manner.”

Scholars have in fact distinguished, since the 18th century, two precise moments in the production of the Brescia-born painter. The “first manner” is the one that, Cittadella wrote, is configured as characterized by “a very studied painting and [...] a sodo gusto learned from watching many good masters,” while in the second manner “to satisfy the many duties that were placed on him, he no longer cared for so much diligence and effort, safe in the stroke of his brush he accelerated the manner, using in his paintings greater vagueness of hues.” Or again, to use the words read in Girolamo Baruffaldi’s Vite de’ pittori e scultori ferraresi (the author who speaks of the “paesi vaghissimi” of the title of the BPER exhibition, where “vaghi” is to be understood in the eighteenth-century meaning of “enchanting, attractive”), “in the first years of his residence in Ferrara he painted with good taste, beautiful order and finesse, but his works having met with public approval, and grown to crowds of duties, he hastened his brushes, and changing his method, adopted vaguer tints, and more rested on truth than perfection.” There is indeed a rather obvious caesura in Zola’s art (the paintings of Gerusalemme Liberata and those once in the Monte di Pietà could be traced back to the first phase, while theAndata a Emmaus to the second), but one that appears to be motivated not so much by reasons of contingency as by a different orientation of the artist, who in his maturity approached more the scenographic painting of Marco Ricci, grasping above all its more “wild” aspects, so to speak, as Eugenio Riccomini also noted. In essence, in the second phase of his career Zola welcomed instances closer to the art of Salvator Rosa read through Ricci’s painting.

These are all characters highlighted well by recent critics and further emphasized on the occasion of the exhibition Paesi vaghissimi. Giuseppe Zola e la pittura di paesaggio (Giuseppe Zola and landscape painting ), which relaunched with a certain vigor the figure of the Ferrara artist, inserting him, moreover, in the path of enhancement of BPER Banca’s collection, which continues unabated, alternating significant exhibitions in the room of the Gallery in via Scudari reserved for temporary exhibitions, which since 2018 have successfully flanked the works of the collection on permanent display. The one that brought to the public the selection of eight paintings by Giuseppe Zola chosen by Lucia Peruzzi to provide an icastic summary of the artist’s career was, moreover, the BPER Gallery’s first exhibition on landscape painting, representing an important opportunity for in-depth study of a little-known artist who was, however, among the most modern and up-to-date landscape painters of the Italian 18th century.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.