The Arc de Triomphe, history of a symbol of Paris

It concludes these 33rd Olympics held in Paris, 100 years after the previous Olympic Games were held in the French capital. Athletes, before returning home, will be able to choose from a wide range of souvenirs with various references to artistic heritage. Eiffel Tower, of course, but also pins with a reproduction of the Arc de Triomphe. The national monument where the French state brings its grandeur to life (another 50 meters, with a width of 45 and a depth of 22 meters) is a quintessential patriotic symbol being a place of celebration of victories and battle deaths in France’s long history. In fact, here has been the tomb of the Unknown Soldier since 1920, with a perpetual flame revived every day at 6:30 p.m. in a solemn manner. The last miles of the Tour de France pass through here. With its majesty it represents that national spirit typical of the French.

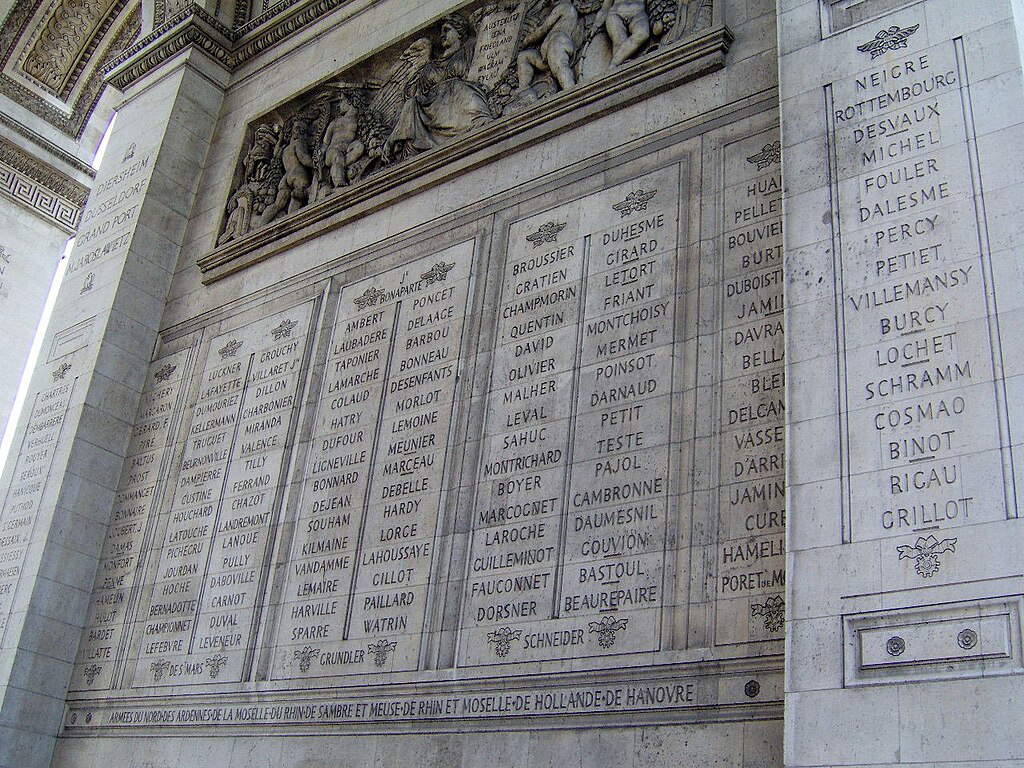

On the interior walls are engraved the names of the places of the great battles and the generals who led the French armies. On the outside, the 4 pillars have high reliefs evoking Napoleon, the young soldiers who went to war, resistance, and peace. There is the whole concentration of symbolism that outlines the nation that was built. Built in the neoclassical style, the Arc de Triomphe sits at the center of what is now called Charles De Gaulle Square, but which until 1970 was called Place de l’Étoile, meaning “of the star,” because of the twelve avenues that radiate out from this square. One of them is the famous Avenue des Champs-Élysées, the avenue of the Champs Elysees that conduits to the Place de la Concorde and the Louvre, while on the opposite direction, via the Avenue dela Grande Armée, one arrives at theArc de la Défense, in the modern business district. The location therefore is of extreme importance in the city’s urban planning map.

It was intended by Napoleon Bonaparte, who upon his return from the Battle of Austerlitz decided that this feat should be worthily celebrated: soldiers who fight for their country should be given proper honors. Inspiration was given by the ancient Romans who, with large architectural structures in the shape of gateways, such as the Arch of Titus, had created a symbolic place to pass through as a sign of prestige, where tribute could be paid to soldiers who had returned from battle. Napoleon, in 1806, then gave the order for construction, but to see the work completed would require waiting thirty years and the change of several monarchs. Today you can visit it with a paid ticket or with guided tours, costing slightly more, which last an hour and a half. You enter inside and can climb (284 steps) to the top, passing through the museum area, where there is a viewing terrace. A 360-degree view with in the skyline the other iconic monument of Paris, the Eiffel Tower, not far away.

The history of the Arc de Triomphe

What is now a large traffic island, was a mound in the late seventeenth century, and the surrounding area was involved in a project for a large green area. In the eighteenth century, the gardens that were created on marshy land below were christened “Champs-Élysées,” a reference to Greek-Latin mythology . When Napoleon took office, as mentioned above, he wanted the battle of Austerlitz of December 1805 to be worthily commemorated, and for the project he chose the architect François Thérèse Chalgrin, assisted by Jean-Arnaud Raymond, who proposed building the Arc de Triomphe to the west of the Champs-Élysées so that it could be seen from the Palais des Tuileries, which was the imperial residence at the time.

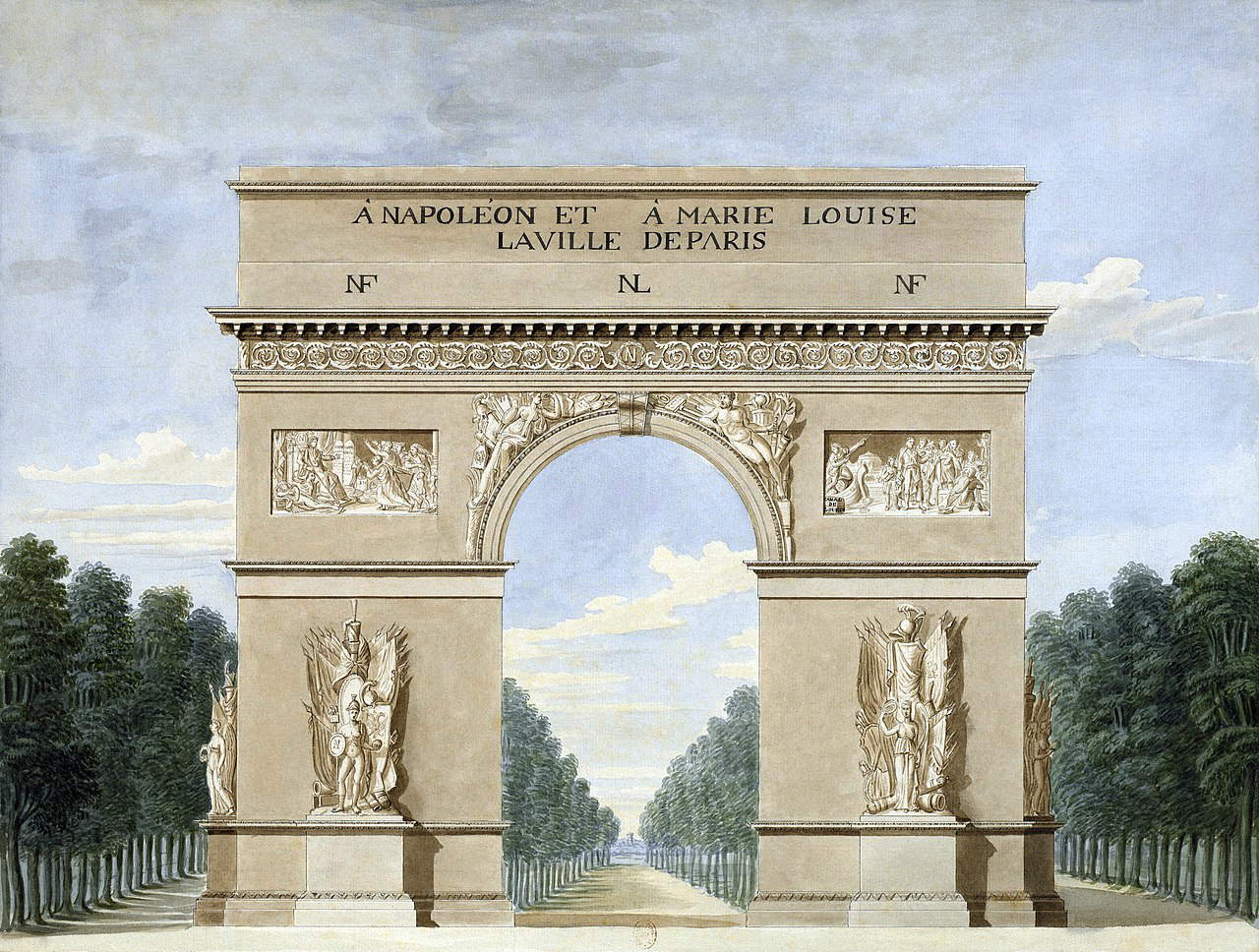

The foundation stone was laid on August 15, 1806, Napoleon’s birthday, but four years later, on the day of Napoleon’s marriage to Marie-Louise of Austria, the construction of the Arc was still in high gear: the base of the 4 pillars still only reached ground level, having sunk the foundations 8 meters underground.

Bonaparte’s desire to have a monument to parade under was high enough that he requested that a temporary arch be built, a temporary installation made of wood and canvas to greet Napoleon himself and his wife. The temporary version was prepared in full size following the original design model, costing 511,000 francs. The temporary installation was useful to the architect because it allowed him to study new solutions that brought changes to the design. Work continued but after the fall of Napoleon stopped until King Louis XVIII, on October 9, 1823, decided to restart it to honor, however, not Napoleon’s army but the Army of the Pyrenees, which had just reinstated Spain’s King Ferdinand VII on his throne. The kingdom of France claimed this victory as its own.

The commission was given to Louis-Robert Goust who was later joined by Jean-Nicolas Huyot: the two followed Chalgrin’s designs. When Louis XVIII died in 1824, he was succeeded by his brother Charles X who continued on this path. In 1830 Charles X abdicated and Louis Philippe I came to the throne and gave a mandate to finish the work, changing the dedication again: “To the Armies of the Empire and the Revolution.” The then Minister of the Interior, Adolphe Thiers, gave the order to make the allegorical decorations, high reliefs, frises, spandrels, shields and balustrades. And to get the work completed quickly he had many people put to work: Cortot, Etex, Rude, Lemaire, Seurre, Feuchère, Chaponnière, Gechter, Marochietti, Pradier, Bra, Valois, De Bay, Jacquot, Laitie.

On February 20, 1836, Lieutenant General Saint-Cyr Nugues proposed three lists of names to be engraved and remembered in future memory: 30 decisive battles of the Revolution and Empire for the top, 96 feats of arms and 384 generals to decorate the pedestals. A list over which controversy broke out after the 1836 inauguration: many began pointing out generals worthy of remembrance and equally important battles, so much so that it was immediately arranged to remedy the situation by engraving new 128 names of generals and 172 battles. Even the name of Victor Hugo’s father, Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo, was forgotten. A year later, Hugo wrote “À l’Arc de Triomphe,” a long poem that ends with these lines, "Whenmy thought, thus aging your attack, makes you a magnificent past, then under your greatness I bow in terror, admire, and, pious son, passing by that art soul, I regret nothing before your sublime wall than Phidias absent and my father forgotten."

The decorations

The walls of the four pillars on their outer sides have sculptural groups in high relief representing various specific historical events, and were made between 1833 and 1836 by François Rude, Jean-Pierre Cortot, and Antoine Etex. The first, on the side facing the Champs-Élysées, evokes The Departure of the Volunteers in 1792, when there was the conscription of 200,000 men ordered by the Legislative Assembly to organize the defense of France in the face of foreign armies arrayed against the revolutionaries. It was made by François Rude between 1833 and 1836 with the choice not to use depictions of weapons or clothing proper to the period, leaning toward a totally allegorical representation. The use of the Romantic style, explains the Arc de Triomphe guide, seeks to achieve a universal dimension and to symbolize the struggle of a people, whatever they may be, to defend what belongs to them. Then there is a high relief depicting the genius of Liberty, in the form of a winged woman who cries out in the face of enemy invasion, and invites the people to fight by brandishing her sword. Below this figure, a bearded warrior in armor drags a naked youth by the shoulder, waving his helmet as a sign of departure and recovery.

Another relief, by Antoine Etex, is devoted to the Resistance, specifically resistance to the invasion of foreign forces arrayed against Napoleon in 1814. Russia and the Austrians had in fact invaded France reaching as far as Paris. Resistance to invasion is a preeminently national theme: in the face of the enemy, all internal dissensions within a country must be erased so that the nation can regain its unity and preserve the integrity of its soil. A naked warrior, standing with his right hand armed with a sword, is about to set out to defend his country. To his right, an old man tries to hold him back. To his left, his wife, holding their child, is also trying to convince him to stay. The bearded knight without armor falls from his mount, as if struck by lightning. He symbolizes the sacrifice of a patriot for his country. The Genius of the Future, with wings spread and flame on his forehead, dictates the soldier’s duty of endurance."

Also facing the Avenue des Champs-Élysées is Jean-Pierre Cortot’s The Triumph of Napoleon . The artist chooses to illustrate the year 1810, the year of the expansion of Napoleon’s empire through numerous conquests and battles, but also through his marriage to Marie-Louise of Austria. Napoleon is here dressed in the old-fashioned way, crowned with a Victory. In the background to the right, a kneeling man with bound hands presents a prisoner at the feet of his victor. On the left, the allegory of a city also kneels before its conqueror presenting a protective hand. Behind her, the Muse of History engraves the Emperor’s triumphs on a tablet. A winged Fame towers over the scene, blowing a trumpet and brandishing a banner against a background of palm trees, a tree evoking Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt.

Also by Antoine Etex is the relief with Peace, which faces the Avenue de la Grande-Armée, and is a continuation of the sculptural group of Resistance. After the Treaty of Paris in 1815, peace returned to France, with the interlude of Napoleon’s return in the Hundred Days, and in the relief we see the soldier in the center of the composition putting his sword in its scabbard, with the war now over. The plow, bull, and plowman symbolize the return to flourishing agriculture after the vicissitudes of war. The mother and child represent the family and the return of education. All the basic activities of a prosperous nation are united. Minerva dominates the group as goddess of victory and inspirer of the arts and works of peace.

The Unknown Soldier

It was the tears over the huge number of soldiers who died during World War I that provided the impetus to find a worthy way to remember the sacrifice of more than 1.4 million who died during World War I. Many of whom fell on battlefields with no chance of being identified and brought home to their families. The government posed the question of whether those endless stretches of bodies in the theaters of war should be retrieved for burial by their families or whether it would be more appropriate to bury them in cemeteries raised at the sites of the fall in the field.

The idea of creating a place to pay honors to a soldier and with him symbolically to all the dead took shape, and they began to think about the most suitable place to bury this body. The Pantheon was discarded because of the religious origins of the building and also because the belief was that a place should be chosen to pay tribute not to a great man, great writer or scientist, but to the greatest of all, representing the French citizen who sacrificed himself for his country. Here then was opted for what was the equally impactful monument in town, secular, already used for funeral ceremonies and for the remembrance of those who had died in battle.

On July 14, 1919, the day after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, Georges Clemenceau organized the Victory Parade. The man known as the “Father of Victory” chose the Arc de Triomphe as the setting for the parade and to set up a specially constructed cenotaph to pay homage to the dead though without a body inside. It is an immense tomb eighteen meters high and weighing 30 tons, with the gilded sides of the cenotaph displaying winged victories and the inscription “To those who died for the fatherland.” Here a body of the soldier was buried under the Arch, it was covered with a stone slab inscribed “Here lies an unknown soldier who died for the fatherland 1915-1918.” At one end of the slab was placed the brazier where to burn a flame perpetually. The fire mouth was surrounded by a metal circle with 25 swords engraved on it with the tips pointing toward the center.

Solemn ceremonies

From that time, the Arc de Triomphe became the monument for France’s institutional ceremonies, but it was as early as the mid-19th century that the monument began to be considered as a suitable setting for solemn events and funeral ceremonies. The first was when, in 1840, Louis Philippe sent his son, the Duke of Joinville, to St. Helena to exhume and repatriate the ashes of Emperor Napoleon. On December 15, a monumental float crossed the Arc de Triomphe in front of a crowd of thousands. Also present on that occasion was Victor Hugo, who had the following to write about the feelings of that day: "A mediocre operatic set occupies the top of the triumphal arch, with the Emperor standing on a chariot surrounded by Fame, who has Glory on his right and Greatness on his left [...] This is a monumental gibberish." In fact, the last architect of the Arc de Triomphe created a crowning for the Arc de Triomphe in 1834 (which is no longer there now). Originally, it was the figure of France that was represented in the center. On the eve of the return of Napoleon’s ashes, Blouet replaced France with Napoleon in imperial dress.

Hugo himself was given a state funeral at the Arc de Triomphe when he died on May 31, 1885: thousands of French people flocked to the ceremony, and the body and a huge catafalque, in the shape of an urn, 22 meters high, were placed under the Arc. On August 3, 1842, the Arc de Triomphe again welcomed a funeral convoy, that of the Duc d’Orléans. Louis Philippe’s son had died a few days earlier in a carriage accident.

Between 1848 and 1852, the Arc de Triomphe was used for events related to civic worship and became a political and military rallying point, spontaneously contributing to strengthening its secular symbolic function. In 1848, for example, the government wanted to organize here the Fête de la Fraternité (the Fraternity Festival dedicated to the National Guard and the Army) by having bleachers erected under the vault. It was the first time that the Avenue des Champs-Élysées was decorated with the tricolor flag on both sides for the big military parade, at the edges of the avenue many women with bouquets of flowers also tied with tricolor ribbons. As evening arrived, 21 cannon shots were fired at 9 p.m. to greet the arrival of the provisional government at the podium. Always Place de l’Étoile was chosen for the spectacle with which the coming into force of the Constitution on November 19, 1848, was celebrated with a grand fireworks display. Same location for the military parade the following year for the important anniversary of the first anniversary of the proclamation of the republic

Equally important was the entry into Paris of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon III) after being proclaimed emperor, December 2, 1852. He entered by crossing the Arc de Triomphe with his troops. Napoleon III wanted to celebrate his uncle Napoleon I every year with a performance every August 15 in the Arc de Triomphe square.

In 1859 a law established the annexation of neighboring municipalities by enlarging the city’s boundaries and to enhance the city’s monuments, and a major redevelopment of the Place de l’Étoile was proposed by Baron Haussmann to Napoleon III. To enclose the square itself, Hittorff designed twelve star-shaped avenues connected by four-story mansions of identical architecture. On May 23, 1863, an imperial decree renamed the Promenoir de Chaillot Place de l’Étoile.

The history of the monument is told to the visitor in the museum set up in the hollow part of the monument. Entering through a door in the inner part of a pillar, one ascends a spiral staircase of 240 steps that leads to the room where the museum area is set up with the miniature model created by architect Georges Chedanne and sculptor Henri Bouchard, memorabilia, panels, photos, and various screens with historical explanations. Taking another 40 steps, we are at the top, with a view of the panoramic terrace over Paris and the proximity of 20 monuments on all sides. We can also see the Basilica of the Sacred Heart in the emblematic Montmartre district, the La Défense business district and its skyscrapers, the golden dome of Les Invalides, the columned dome of the Pantheon, but also the towers of Notre-Dame Cathedral in the distance, the great Tour Montparnasse, all the way to the Centre Georges Pompidou. All the best-known monuments of Paris.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.