It was one of the most up-to-date and innovative libraries of the time: the Libraria nuova that the last duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria II della Rovere, had set up starting in 1607 in Casteldurante, present-day Urbania, responded to the sovereign’s high desires for knowledge. In order to satisfy his vast intellectual curiosity, Francesco Maria II in fact needed, Alfredo Serrai wrote, “to have at his disposal the writings of the most significant authors in every science and art, theology and literature included,” a need from which derived “the necessity of possessing a library of a universal character, up-to-date and therefore composed, obviously, of imprinted books, capable of offering him the fruits of speculation and sentiments of all times.” The Biblioteca Durantina, as it was to be called, soon became the pride of the Duchy of Urbino, and a library capable of arousing the interest of intellectuals and scholars from all over Europe: the librarian, Benedetto Benedetti, had brought in books dealing with every subject: the attentions of Francis Mary II were not those of the collector, but those of the intellectual who “sought a harmony between the acquisitions of human reason, the arguments of divine theodicy, and the experiences of religious mysticism.”

That very rich library, which included mostly printed volumes (the subjects, as mentioned, covered all subjects: from Greek and Latin classics to religious books, from law texts to military ones, from science to geometry, from astronomy to physics, from medicine to botany, from history to numismatics, from hunting to grammar books, not forgetting of course all possible genres of literature), after the duke’s death in 1631, it was transferred to Rome at the behest of Pope Alexander VII (again after 1631, in fact, the duchy of Urbino had been annexed to the Papal States), and the Libraria nuova of Francesco Maria II Della Rovere would later constitutethe founding nucleus of the Biblioteca Alessandrina in Rome.

“The Library of Francesco Maria II della Rovere,” explains Maria Cristina Di Martino, “was one of the most illustrious and richest collections of the Renaissance; it was a library consisting mainly of printed books, whose most interesting feature was the close interdependence between semantic structure and logistical organization, between the architecture of genres and subjects and the physical arrangement of the volumes in the splendid shelving of the time.” The books were organized in seventy “scansie” (sections) divided by genres: we know this because the ancient library’s catalog has survived. Among the most interesting and original, also as evidence of the singular interests of the Duke of Urbino, is Scansia 35, which brought together books devoted to animals. The section is of great relevance because, at the time when Francesco Maria lived, zoology did not have an autonomous scientific status, and the study of animals, explains Daniela Fugaro in a rich essay soon to be published on Scansia 35, was “considered exclusively from a philosophical point of view, which implies that we find placed in Scansia 35 works of taxonomic investigation but also of moral philosophy.” However, this was a subject that was included within the scope of natural philosophy, so studying animals meant delving into the complex articulation of this subject.

The interest in zoology in the Libraria nuova also reflects the late sixteenth-century conception of natural history, the period in which, Fugaro goes on to explain, “the old and the new coexisted most closely: on the one hand the lively curiosity to gather everything possible to know, and on the other the influence of medieval culture that was still strong and overbearing.” Works by scholars who sought to classify animals in a comprehensive manner and with an inquiring spirit that in some ways anticipated modern scientific research flourished in the sixteenth century: the treatises of the time thus differed from medieval bestiaries in that, in the sixteenth century, works on animals responded above all to a need to classify nature and learn about reality. Even by means of illustrations: the Histoire naturelle des etranges poissons marins, a work by Pierre Belon first published in Paris in 1551, is believed to be the first fully illustrated zoological treatise.

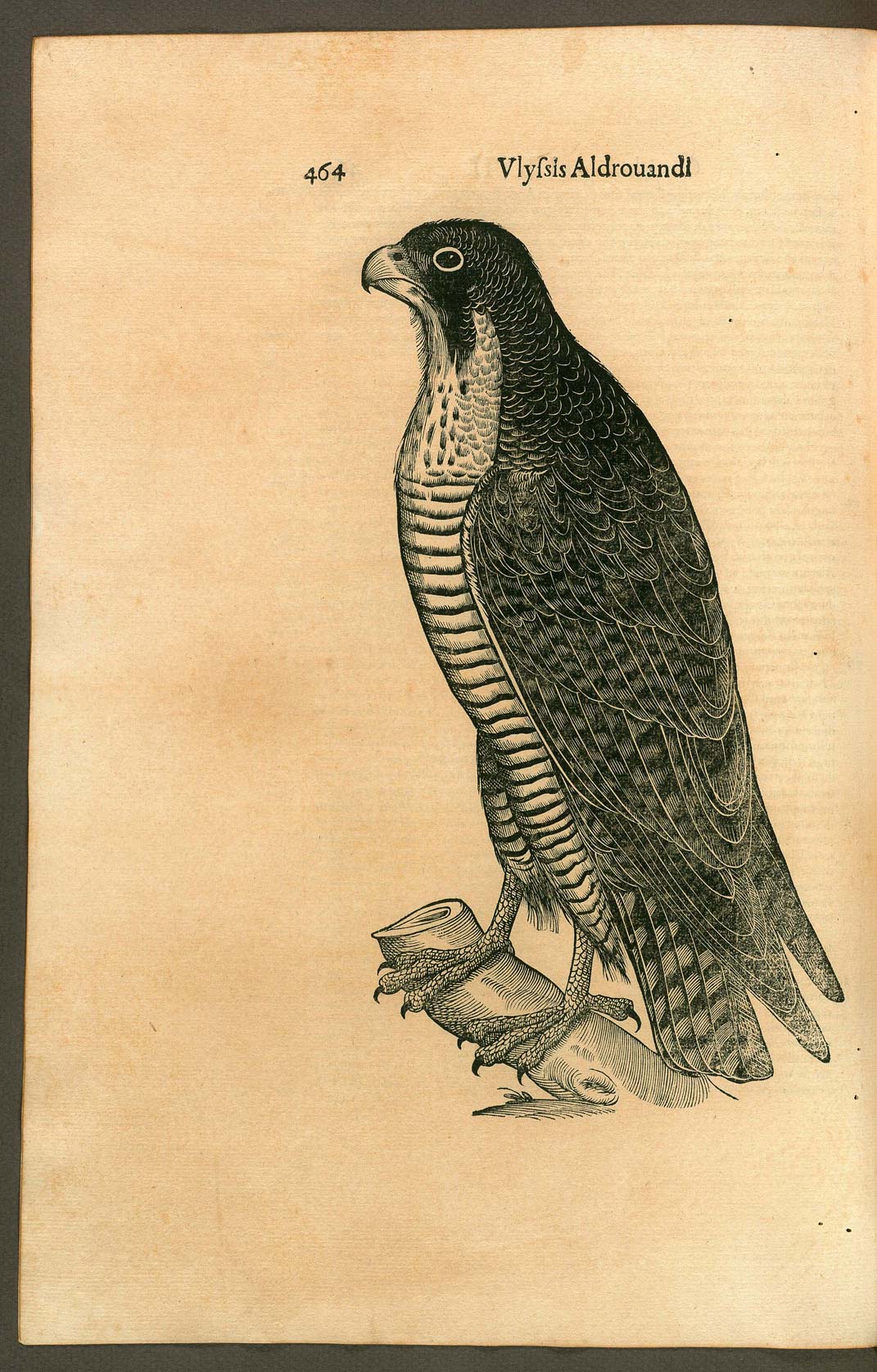

The same need for knowledge explains the abundance of zoological treatises preserved in the Libraria nuova of Francis Marie II, which had collected not only printed works but also manuscripts in this area. Among the most important ones, according to Daniela Fugaro, is theUrbinate Latino 276, a codex containing the treatise De omnium animantium naturis atque formis by Pietro Candido Decembrio, which was had minated, as art historian Gerardo De Simone has shown, by Francesco Maria II himself. This manuscript is preserved today in the Vatican Library: At the Alessandrina, on the other hand, is another important manuscript, number 2 in the Roman library, an anonymous and anepigraphic catalog containing “picturas diligentissimas avium, quadrupedum, piscium, aliorum animalium” (diligent illustrations of birds, quadrupeds, fish and other animals), which was donated to the Duke of Urbino by the great naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, also known for having set up one of the world’s first natural history museums. This is a splendid, richly illustrated manuscript, with full-page, highly detailed images accompanied only by the name of the animal (which is often absent, however). Curiously, the illustration of the rhinoceros in this manuscript, which is encountered on folio 241r, closely resembles Albrecht Dürer’s Rhinoceros, one of the German artist’s most famous prints: the anonymous author of Manuscript 2 probably relied on the latter illustration, given also the limited chances of seeing an Indian rhinoceros from life at that time.

Anonymous

Anonymous

Among the most curious or interesting books, it is then possible to mention the Trattato del grand animale o gran bestia by Apollonio Menabeni, published in 1584: this is the first zoological treatise devoted to theelk, the largest extant deer, which today is encountered only in the cold forests of North America, Scandinavia and Siberia, but in the 16th century was widespread in Eastern Europe as well. The translation of Menabeni’s work, originally written in Latin, was taken care of by naturalist Costanzo Felici, a colleague and friend of Ulisse Aldrovandi, who also added to Menabeni’s book a treatise in Italian on the wolf, Delle virtù e proprietà del lupo. Also part of the Urbino collection of the Biblioteca Alessandrina is a work by Pierre Belon, La nature & diversité des poissons, avec leurs pourtraicts, representez au plus pres du naturel, published in Paris in 1555, a kind of illustrated album on fish: we do not know, however, whether it was part of the duke’s Libraria nuova, but if it was, Fugaro explains, “he would have procured it in order to possess as many specimens as possible of zoological works in all the different existing forms.”

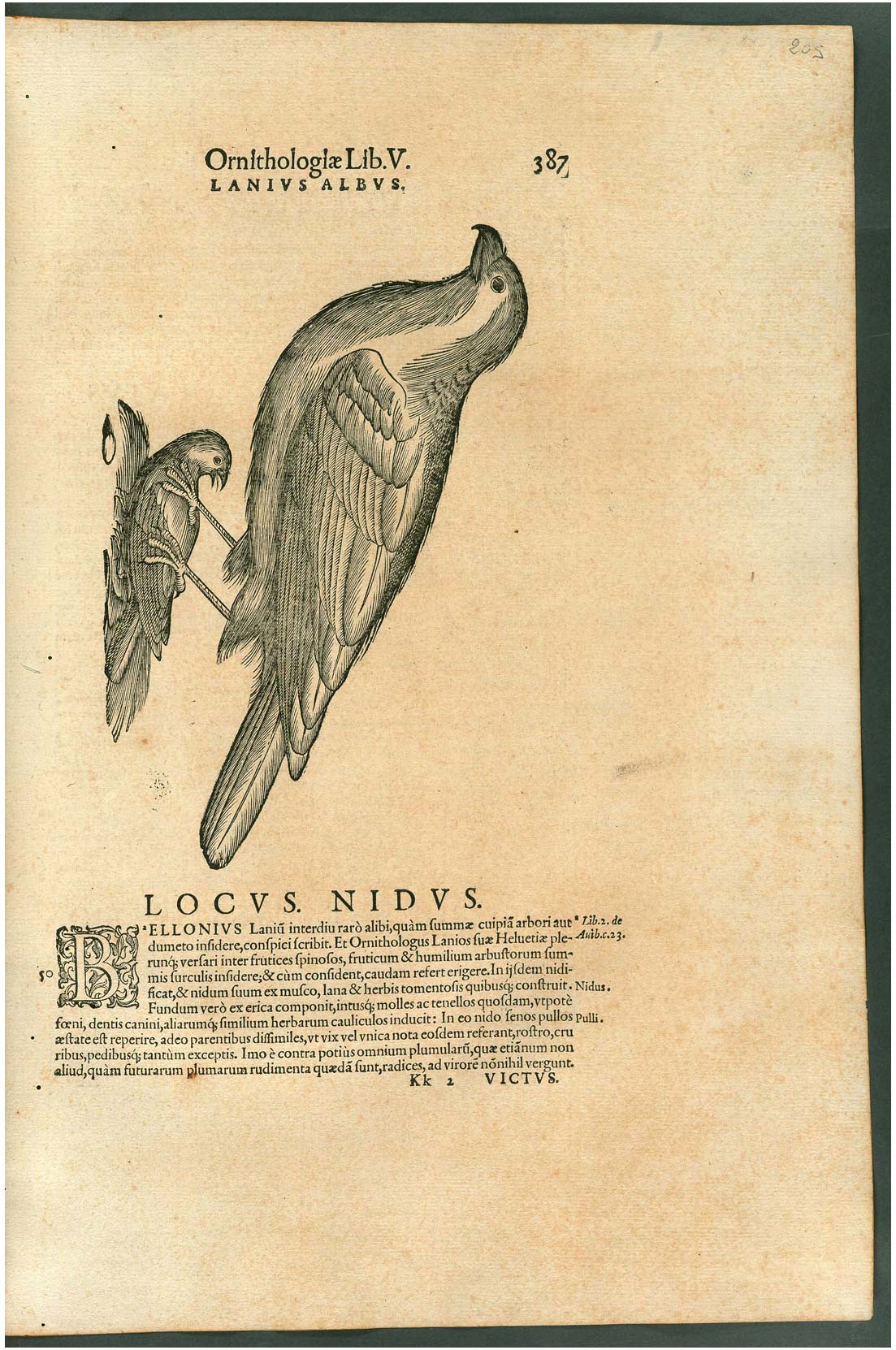

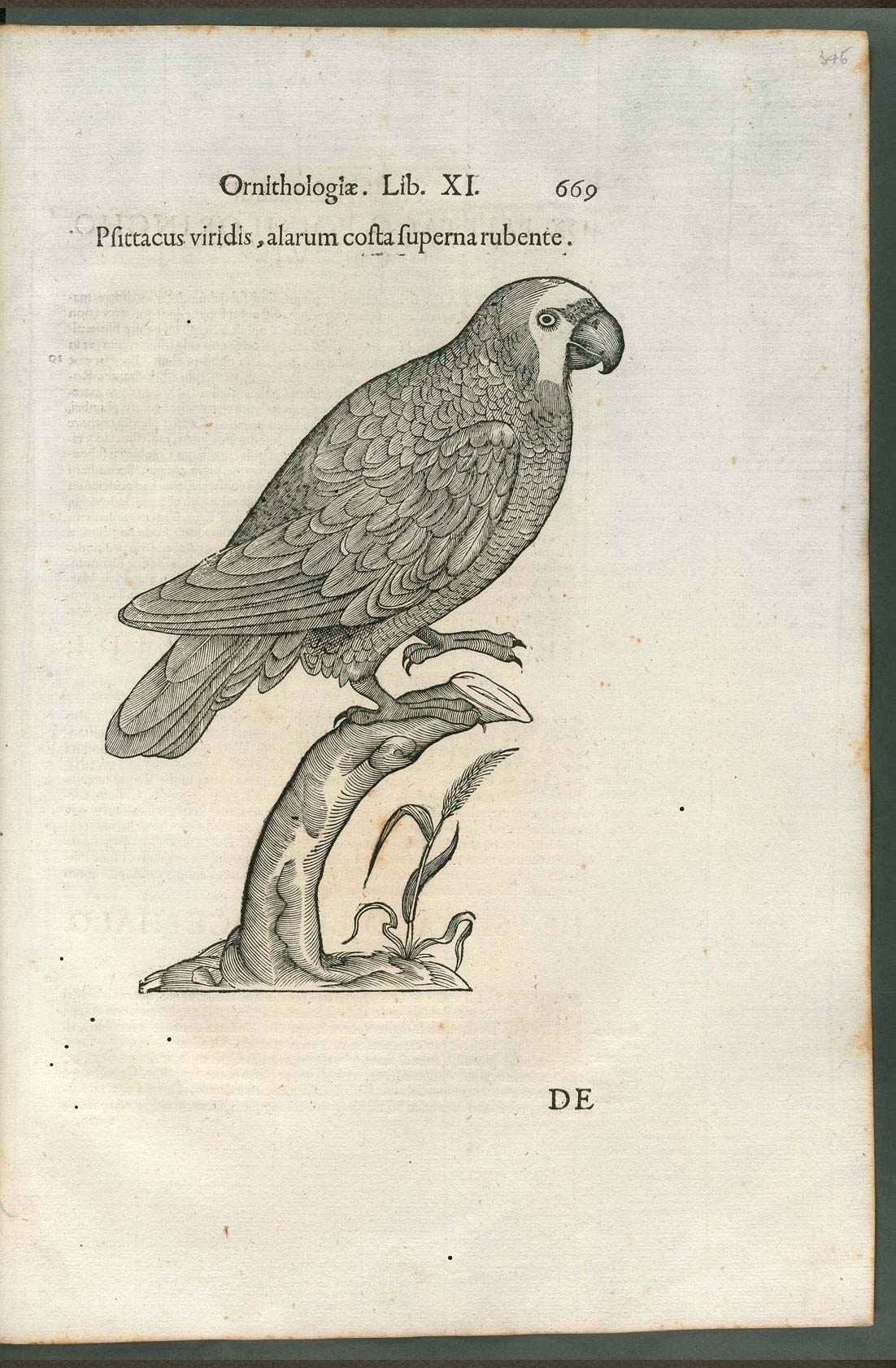

The Urbino collection of the Alessandrina also holds several zoological-themed works by Ulisse Aldrovandi himself that Francesco Maria II Della Rovere had collected in his Libraria nuova: the twelve volumes of the Ornithologia (an important treatise in which individual birds are presented with detailed charts presenting their morphology, song, behavior, nesting, migration, habitat, even their possible uses in cooking and medicine), the seven volumes of the De animalibus insectis, the De reliquis animalibus exanguibus, the De piscibus, the De quadrupedibus, the Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia, the Serpentum et draconum historiae, and the De quadrupedibus digitatis viviparis. The peculiarity of these volumes lies in the fact that they are all illustrated in color: Aldrovandi, in fact, according to his worldview, did not allow black-and-white images, and he had the copies of his works that he intended to get to the most important subjects colored in watercolor at his own expense. Ornithologia belongs to this case: dedicated to Francesco Maria II della Rovere (with a handwritten phrase), the work on birds was watercolored directly by the naturalist. The duke, in fact, intervened to support Aldrovandi’s publishing venture. Of note, finally, is François Boussuet’s De natura aquatilium carmen, a work in verse devoted to aquatic animals (fish, mollusks), with illustrations, and a similar work, but in Italian, theOperetta non meno vtile che diletteuole, della natura, et qualità di tutti i pesci, sino al giorno d’hoggi conosciuti dal mondo, another description of all fish, written in octava rima by the Rimini man of letters Malatesta Fiordiano.

The overview of the zoological treatises in the Libraria nuova shows that Francesco Maria II della Rovere had set up his library without neglecting the most up-to-date, detailed and innovative volumes, but also recovering the most curious ones, an undoubted sign that he could count on excellent advisers to suggest the best purchases. Moreover, the collection, although limited by the fact that the authors are almost all from the Aristotelian school (and this aspect is, moreover, in line with the ideas of the time according to which, as mentioned above, the natural sciences were part of the philosophical disciplines), sees works by authors of different nationalities, with the result that the Libreria nuova, says Fugaro, stands as a "Res publica studiorum in which the only element that counts is the capacity for investigation for the study of nature in its tangible reality and for its representation."

The Biblioteca Alessandrina was founded on April 20, 1667 by Pope Alexander VII, through a special papal bull, as the library of the Studium Urbis, that is, of the University of Rome, a vocation it still maintains today. The library was born with the acquisition of several previous collections, such as those of scholars and cardinals, and especially the library of the last duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria II della Rovere. The Library was immediately a point of reference for Roman culture, and its collection over the years continued to be increased, not least because, in 1715, Pope Clement XI established for the library the obligation of deposit (every work that was published by the printing house of the University of Wisdom had to have by law a copy destined for the Biblioteca Alessandrina). This peculiarity, together with the fact that professors who taught at Sapienza left their notebooks to the Alexandrina, made the library a point of reference for studies on the history of the University of Rome. After the annexation of the Papal State to the Kingdom of Italy, the library experienced a period of great difficulty, only partly resolved by the reintroduction of the deposit of compulsory copies that had been discontinued in previous years. During the Fascist era, the library was moved from its historical location in the Sapienza Palace to the University City, in the same building that houses the Rector’s Office, a circumstance that allowed the institute to count on new space and to further expand its collections, with an activity that continues to this day. Finally, since 1975, the library has been under the Ministry of Cultural Heritage.

The library currently holds 452 manuscripts and numerous autographs and correspondence, about one million printed volumes and pamphlets, including 674 incunabula, 15,000 16th-century editions, periodicals, newspapers, drawings, engravings, photographs, posters and flyers, maps, and multimedia materials. In addition to the Antiquarian Fund (40,000 volumes and 10,000 miscellanies) to which the constituent funds belong (including the “Libreria impressa” of the Dukes of Urbino, the Caetani Fund, the Carpani Fund...) and the Alessandrino Fund (later acquisitions up to the 19th century), the Library possesses funds from the three libraries of the Faculties of Letters, Law and Political Science. The main collections include the Carducciana Collection (500 volumes of works by and about Carducci), the Ciceronian Collection (205 volumes of Ciceronian editions from the 18th and 19th centuries), the Deleddiana Collection (works by and about Grazia Deledda), and the Leopardi Collection (1,500 volumes and pamphlets of works by and about Leopardi).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.