If we talk about restorations, there are not only those that are conducted in a masterful way, that restore a work to its optimal legibility conditions, that bring back lost colors, that manage to give a painting or a sculpture an appearance similar to what it might have had originally. As in any field, things can go wrong in restoration, so there can be restorations that are done badly, or whose results are strange and divide critics, or there can be disastrous restorations because they are conducted by personnel with no expertise. In this gallery we look at the ten worst restorations of recent times.

1. Elías García Martínez’s Ecce Homo restored by Cecilia Giménez.

This is surely the most famous clumsy restoration in history. It all began in 2012, when a fresco at the Sanctuary of Mercy in Borja, a village of five thousand inhabitants in Aragon, Spain, needed restoration. The work is an Ecce Homo by Elías García Martínez (Requena, 1858 - Utiel, 1934), a Spanish painter who was a proponent of a late academic art style. The fresco, in 2012, was in a heavy state of disrepair because it had never undergone conservation work: some pieces of plaster had detached and the painted surface appeared ruined in several places. So, in August of that year, an over-80-year-old parishioner, Cecilia Giménez, an amateur painter with no experience in restoration, decided to do the restoration herself: the result, however, ruined the work (probably irreparably), giving it a curmudgeonly appearance, which to many alternately reminded them of that of a monkey, a porcupine, or an animal in general (in Spain, many ironically dubbed the work “Ecce Mono,” or “here is the monkey”). Ms. Giménez’s restoration has become a viral phenomenon and the work thus reduced a kind of pop icon. And the Borja Monastery has also since experienced an unexpected influx of tourists, which has moreover fueled forms of merchandising about the work. The story has also inspired a play and a documentary. And of course, the fresco thus reduced has become a real star.

|

| Elías García Martínez’s Ecce Homo restored by Cecilia Giménez |

2. The Saint George of San Miguel in Estella

We are still in Spain, in 2018: the church of San Miguel, in the historic center of the small town of Estella (Navarre) is one of the most valuable in the area, and it is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site (it is located on the Way of St. James). The oldest evidence of the church dates back to the 12th century, but more recent works are also preserved inside: one of these is a polychrome wooden statue depicting a Saint George on horseback, most likely dating from the 16th century. Again, the work had lost its original coloring and was in urgent need of restoration. However, the inexperienced restorer (called directly by the parish), in an attempt to restore the work to its original colors, ended up spreading the backgrounds evenly, giving the poor Saint George the appearance of a cartoon. The story here, however, has a happy ending: concerned about the dreadful outcomes of the restoration, the local administration, which took over from the parish in the management of the affair, immediately ordered a new intervention, this time a professional one that remedied the errors of the previous one. And finally, a sanction, both for the author of the restoration and for the parish.

|

| The Saint George of San Miguel of Estella |

3. The wooden group from the sanctuary of El Rañadoiro.

Last year again, again in Spain, this time in El Rañadoiro, a village of a few souls located in the mountain range of the same name in the Asturias region. The village shrine houses a 15th-century wooden group depicting the Madonna and Child and St. Anne, and other sculptures also made of wood from the same period, such as a St. Peter and other saints. Again, the script was the same as in Borja: a local amateur painter, María Luisa Menéndez, took over the restoration of the works with the approval of the parish priest. The lady had the nice idea of covering the ancient statues with fluorescent dyes, eventually smearing the works, so much so that the education councilor of the Principality of Asturias had spoken of “a revenge rather than a restoration.” For her part, Ms. Menéndez defended herself by asserting that those colors seemed right to her, and people would like them. From the result...you wouldn’t know it!

|

| The wooden group at the shrine of El Rañadoiro |

4. Our Lady “Maggie Simpson”

The site of the misdeed this time is Canada, and it was preceded by another misdeed. We are in the town of Sudbury, Ontario, in 2016: the Catholic Church of Sainte-Anne-des-Pins houses a 20th-century statue, depicting a Madonna and Child, which has no particular artistic merit. The work, however, suffers an act of vandalism, and the head of the Child is severed cleanly. The cost of restoration is estimated at about ten thousand Canadian dollars (just under seven thousand euros). A local artist, Heather Wise, offers to do the work for free, and she is granted permission. However, the result is terrifying: the new head of the Child, made of terracotta, looks monstrous, and the crown is vaguely reminiscent of the hair of Maggie Simpson, the character from the hit television series (and, to make matters worse, the head is also beginning to melt in the rain: the work is in fact outdoors). Wise, in an attempt to defend his creation, explains that it is simply a temporary intervention while waiting to make the head in stone, but it is probably already too much as it is, and the story ends up in all the newspapers. The catastrophic intervention has a silver lining, however: the vandal, moved by the media coverage of the affair and perhaps also disgusted by the appearance the Madonna had achieved, gets the church the Child’s head back so that serious restoration could proceed. Heather Wise later asked for her “work” back: and to think that the parish priest, Gérard Lajeunesse, while stigmatizing the botched intervention, had declared that, by now, he had grown fond of the strange head.

|

| Our Lady “Maggie Simpson” |

5. Tutankhamun’s beard

Toward the end of 2014, something went wrong during the cleaning operations of one of the most famous artifacts in the Cairo Museum in Egypt: the mask of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. The employees in charge of removing the mask from its display case to proceed with the cleaning, inadvertently detached the beard from the pharaoh’s chin, and hoping to go unnoticed (and, of course, without saying anything to anyone) had the nice idea of reattaching it with quick-setting industrial glue, of the kind commonly found on the market. But that’s not all: to remove the glue drops that, due to the employees’ inexperience, had dripped onto Tutankhamun’s chin, the workers attempted to scrape them off but ended up scratching the work. Having noticed the damage in January 2015 (and thus the truth emerged), restoration with more suitable materials (i.e., fixatives used at the time of the pharaoh) was commissioned to a team of professionals. And of course, for those responsible for the careless restoration, the avenues of justice were opened.

|

| Tutankhamun’s Beard |

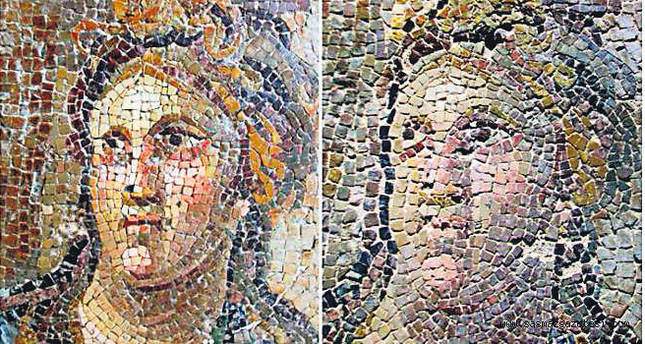

6. The mosaics of the Hatay Museum in Antioch.

In 2015, restorations were conducted on a series of Roman mosaics housed in the Hatay Archaeological Museum in Antioch, an ancient city in southern Turkey. The mosaics dated from various periods between the second and sixth centuries AD, but the interventions had a ruinous effect on the works.The case was raised by a local craftsman, Mehmet Daskapan, who called a local newspaper to let it be known that the mosaics had taken on a hideous appearance, since the original tiles had been replaced with tiles that had shapes, sizes, and colors that had nothing to do with the originals. It is not known exactly how things turned out, partly because there were attempts to downplay what had happened (the Turkish Ministry of Culture explained that these were pictures taken at an early stage of the restoration, when the work had yet to be finished), but the fact is that the restoration was suspended and soon a new operation was carried out to restore the mosaics to their true appearance.

|

| The mosaics of the Hatay Museum in Antioch |

7. The Castle of Matrera

The images of the Matrera Castle (near the town of Villamartín in Andalusia, Spain), a ninth-century fortress that underwent a highly controversial restoration in 2015, which instead of preserving the surviving portions of the ruined castle, built from scratch squared-off volumes to which the stones of the old fortress were applied. The architect in charge of the restoration, Carlos Quevedo Rojas, explained that he did not want to proceed with just a conservative restoration, but that he wanted to restore the volumes, shape, and tone that the tower originally had, making the difference between the additions and the old structure stand out. Opinions were divided between those who considered the restoration a disaster (in the pages of the Guardian, journalist and architect Oliver Wainwright spoke of a “Frankenstein restoration”) and those who praised the attempt to restore the castle to its original Moorish forms. And in some circles it was so highly praised that it ended up in the final of an architectural award, the Architizer A+ Award, and even brought back victory in the “conservation” category.

|

| Matrera Castle |

8. The Castle of Ocakli Ada

Another castle, but this time in Turkey: we are in Sile, a seaside town near Instabul, where the ruins of a fortress dating back some two thousand years, the Ocakli Ada Castle, can be found. Severely ruined, the castle in 2015 saw the end of a restoration project that lasted many years but completely distorted the image of the building. It was rebuilt almost from scratch: the walls were made smooth, battlements were added, and bizarre windows were added that looked like the eyes and mouth of a cartoon character, so much so that on social media the Ocakli Ada castle was renamed “the Spongebob castle,” due to its resemblance to the well-known cartoon character. But the local government defended the work of the restorers, arguing that the castle had been in heavy disrepair for more than a century, that the operations were the result of a long decision-making process, and that the criticism was not based on knowledge of the facts.

|

| Ocakli Ada Castle |

9. The Anyue Buddha

A work dating back to the 11th century, the Anyue Buddha sculpture in Sichuan province (southern China) underwent heavy restoration probably by an amateur restorer in 1995. However, the case only came to light in 2018, when Xu Xin, a tour guide and archaeology enthusiast, posted photos of the restored Buddha on his social profiles (acid colors had been applied to the stone that made the figure, again, look cartoonish, in total disregard of the work’s original appearance), which went viral and forced the authorities to take a stand on the matter. The city administration thus admitted that there would be a crackdown on the management of protective interventions on cultural property, and that in any case in recent years no intervention had been conducted in that manner since.

|

| The Buddha of Anyue |

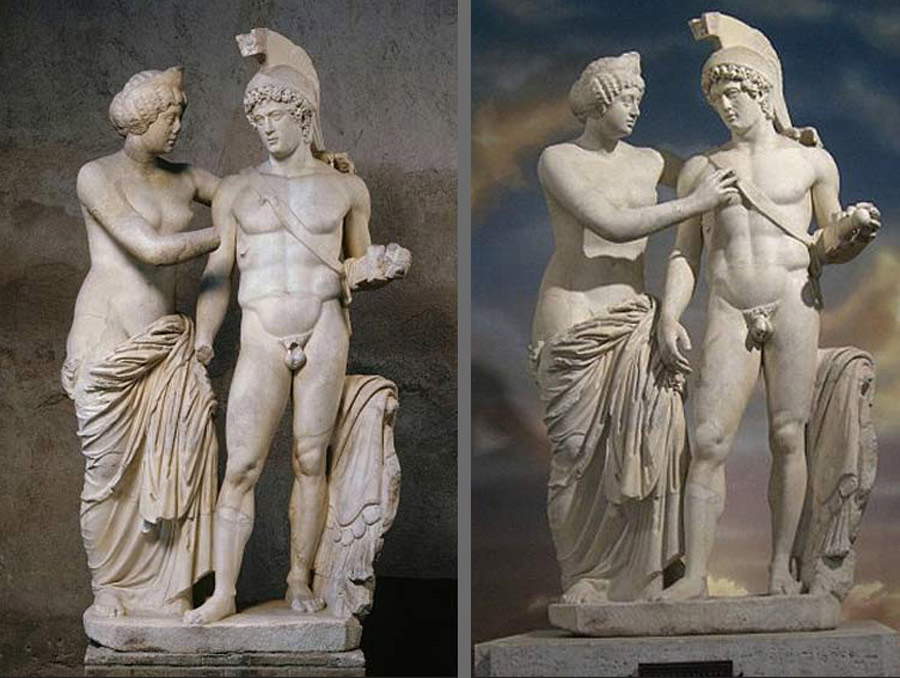

10. Mars and Venus with the “prostheses” wanted by Berlusconi

The roundup ends with an all-Italian case: it is 2010, Silvio Berlusconi is prime minister, and since that year a second-century sculptural group depicting and Venus has been temporarily loaned to Palazzo Chigi. However, Berlusconi evidently resents the fact that the group, found in 1918 in Ostia, is missing some portions (both hands of Mars, the right hand of Venus, the pommel of Mars’ sword, and the penis of the god of war), so he insistently asks that the gaps be made up. The presidency of the council allocates 70 thousand euros for the additions, and the intervention is conducted, in defiance of all criteria of scientificity, which, in modern restoration theory, does not want additions to ancient works that are missing some of their parts. An attempt was made, however, to intervene with as little damage as possible: the operation was presented by the then superintendent of Rome, Giuseppe Proietti, as a totally reversible aesthetic maintenance operation. And in fact the “prostheses” added at Berlusconi’s behest lasted just a little longer than the time he remained at Palazzo Chigi: as early as 2012 the removal was carried out, and the following year the statues were transferred to the Baths of Diocletian, without the additions. The director of the Baths, Rosanna Friggeri, told Corriere della Sera that that reintegration was an experiment, and should be considered as such. “It is a case that does not fit the scientific criteria of restoration,” she had said, promising a quick removal of the added hands and genitals. Which in fact happened.

|

| Mars and Venus with the “prostheses” wanted by Berlusconi |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.