by Redazione , published on 21/03/2021

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

In 1980, Mario Mariotti imagined a futuristic projection show that "opened up" the unfinished facade of the basilica of Santo Spirito in Florence. The work was the forerunner of modern video mapping.

“In Florence’s Piazza Santo Spirito, until Sept. 8, Ball Square. Game scene projection curated by Mario Mariotti and Sergio Salvi. ’Divertissement’ for young and old with music, dance, projections of projects for the facade of Santo Spirito and games of ’crazy ball’.” This brief had been published in a summer 1980 issue of the weekly magazine

L’Espresso and announced an operation that Tuscan artist

Mario Mariotti (Montespertoli, 1936 - Florence, 1997) had designed together with writer

Sergio Salvi (Florence, 1932) for the facade of the

Santo Spirito church in

Florence. The intervention was called

Piazza della Palla and is still considered a pioneering action in the field of

video mapping, very fashionable in recent years. Of course, it was not

video mapping in the current sense of the term, since Mariotti’s were simply slide projections, but it was nevertheless a futuristic action that was a precursor to the modern use of “enriching” the facades of buildings, and it had notable

novel features.

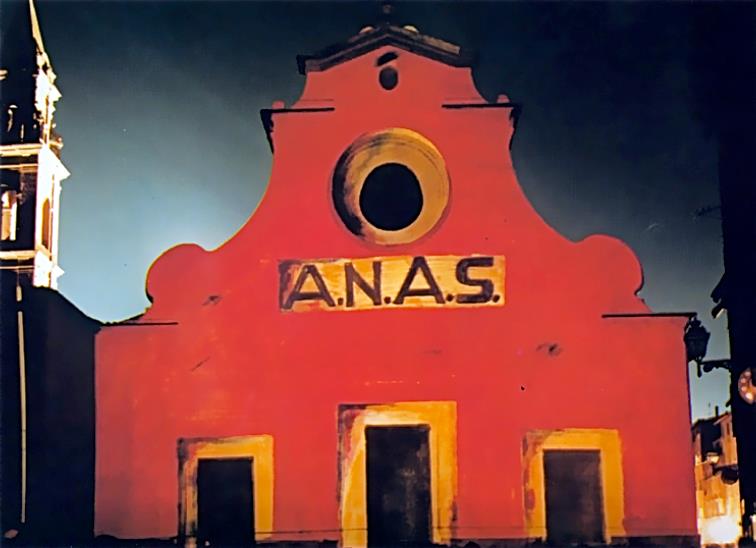

Mariotti’s idea was very simple: it was to “complete,” through video projections, the facade of the Florentine basilica, the best known in the Oltrarno district. The current building is the one designed by Filippo Brunelleschi (Florence, 1377 - 1446) in 1434: the building site, however, survived him, and with several tribulations (there was also a fire, in 1471, that destroyed illuminated manuscripts and works of the pre-existing medieval church) the consecration was achieved in 1481, but it took another few years before the church was truly finished. However, the facade was left unfinished, so much so that in 1791 it was decorated, by “un tal Baccini muratore del luogo pio”, with fake columns and architectural elements: in postcards and photographs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries it is possible to see this decoration, although severely degraded, so much so that in 1960, when the basilica underwent restoration work, it was decided to remove it and leave the church facade simply plastered, as we see it today. Mariotti sensed that that facade, so completely white and smooth, lent itself very well to “indulge” as a screen for video projections: in fact, no element would obstruct the images that would be projected onto the building.

Mariotti’s would not be the first video projection project ever, but it was perhaps the first time (the record is shared with the Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko) in which images were adapted to the surface of a building facade. Already in the 1950s experiments had been made on interiors(Bruno Munari, with his Direct Projections, created art installations created with video projection on walls) and in the theater (a pioneering figure in this regard was the Czech stage designer Josef Svoboda, who had the idea of creating the sets of some shows precisely through video projections). In parallel, architect Paul-Robert Houdin, curator of Chambord Castle in France, had conceived in 1952 the show Son et lumière, projections of lights on the facade of the building, with musical accompaniment. It would be a few years, however, before attempts at video projection mapping, that is, projections in which images were constructed from the mapping of the surface on which they would be projected, so that the image would integrate with the architecture, were developed. And the pioneers in this regard, as mentioned, were Mariotti himself, and Krzysztof Wodiczko, who in the 1980s was the author of numerous artistic video projections ( an interesting archive can be found on his website), mostly of a historical and political nature.

|

| The basilica of Santo Spirito in Florence. Photo Lucarelli |

|

| The facade of Santo Spirito. Photo Francesco Bini |

|

| The facade of Santo Spirito in an early 20th century photo by Alinari |

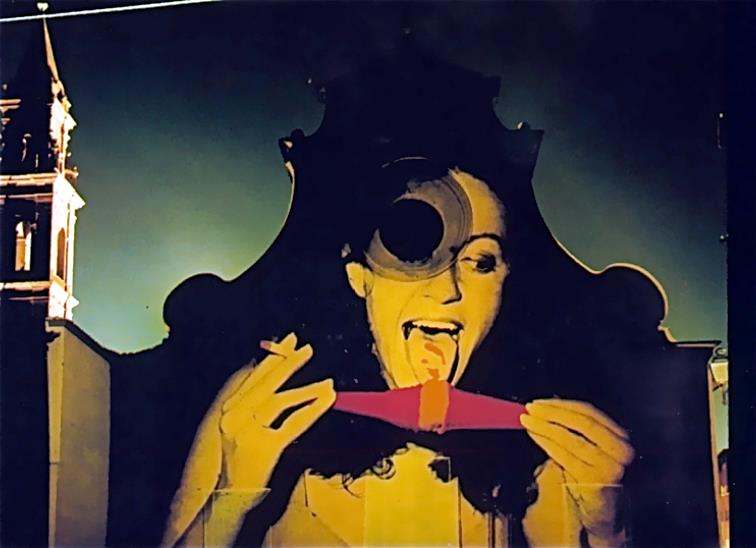

So, in 1980, Mario Mariotti launched a competition open to everyone: anyone could create a drawing to be projected on the facade during the videomapping show. When the contest closed, Mariotti received about four hundred drawings, which were then projected on the facade of Santo Spirito on the nights of July 21 to September 8, 1980. Artists (such as the photographer Gianni Melotti, who came up with the image of a fried egg yolk for the operation that echoed the shape of the rose window), writers, poets, designers, artisans, as well as citizens from outside the world of art and culture participated. And everything had arrived: children’s drawings, photographs, blue skies, famous works of art, advertisements, religious images, proposals for completion with drawings that imagined a real façade, ironic works (such as one that turned the church into a... cantonment house!), a large snake whose head came out of the rose window and whose coils were drawn at the volutes so that the reptile would look realistic, and then also some interesting works that “opened” the façade to show the interior of the basilica. One of these was simply a photograph of the interior, taken so that the interior parts of the church corresponded prospectively to the elements of the façade, and another was a kind of open hinge on the façade that, when opened, showed the interior of the building. The following year, the artist made an archive of the works that had come to him and displayed them in an exhibition at Bar Ricchi, accompanied by the catalog that reproduced them all. Many can be seen in a video on the artist’s official website.

For Mariotti it was a kind of way to fill a blank page in Florence’s history, as well as a great participatory work: one of the goals was in fact to make Florentines feel part of a living community. “The facade project, a cherished theme of the unfinished,” the artist explained with his usual irony, “took Santo Spirito as its model. In the night, the lunar facade of the church reflects the various figures of the collective imagination. The last Medici disappeared so quickly that they did not have time to finish the church facades. And the Florentines, still as full of pride as they were of misery, threw themselves enthusiastically into designing facades (a decent and cheap army at the same time); as soon as Florence was elected capital of the United Italy, immediately the Florentines pulled up from their facade contests the winning designs to be paid for by the nation, and, quick thinking, they managed to pull up two: Santa Maria del Fiore and Santa Croce. Fortunately the capital passed to Rome, the other facades were spared and my design for Santo Spirito saved. So in the night the clear surface of the church was the play and scene of its possible images, projections light years away from the nostalgic certainties of the restorers. As in a commedia dell’arte, the scenery lit up for an ’impromptu’ performance, where the erudite concepts of the lovers were succeeded by the ridiculous laughter of the masks. Now the comedians have withdrawn: the facade has been returned to moon projections (but when, I will be able to project on the moon?) and the Piazza della Palla has returned to being Piazza Santo Spirito.”

What the artist managed to orchestrate in Piazza Santo Spirito, scholar Massimo Mori wrote, was a “party-game-festival that transversally transgressed the rules of the game, the history of the Medici and the geometry of the square, recovering all three in a creative, culturally splendid reformulation operated by numerous artists and poets including Marino Vismara, Daniele Lombardi, Albert Mayr, Claudio Parmiggiani, Henri Chopin, Fabrizio Corneli, Emanuele Mennitti Paraito and many others. That ’facade’ splendor--referring to the well-known projective reconstructions of the front of the church with the use of slides--was due to the urban dissemination of creatives who have always constituted a fertile Florentine pabulum,” at a time when, Mori points out, a sense of disorientation and disintegration was widespread.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Theparticipatory aspect of Mario Mariotti’s work, in addition to its eminently playful character (the exact opposite, then, of Wodiczko’s works) is what most closely approximates his Piazza della Palla to today’s video mapping works, events that often draw large crowds and almost always constitute entertainment shows. Moreover, with his work, Mariotti had also wanted to create a historical connection to the centuries-old history of Florence, setting himself up almost as a kind of continuator of the great Medici festivals, for which huge and ephemeral scenic apparatuses were created, with which the great artists of the past who worked for the Medici decorated the city. And again, the idea of adapting images to the facade of the church places it as one of the first precursors (if not the first ever) of 21st century video mapping.

Today, the facade of Santo Spirito is still the scene of video mapping performances. On an almost annual basis, especially in the summer (but there is also no shortage of projections during the holiday season), artists continue to project images onto the building’s unfinished face. The basilica, for example, is one of the venues of choice for the F-Light festival, which every year enlivens the Florentine architecture precisely with video mapping and light shows. Practices that all take us back to that 1980 precedent, when the imaginative and imaginative Mario Mariotti first thought of transforming the facade of a church into a large blank canvas where the collective imagination could run wild.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.