A “grandiose monument, conceived for Via dei Fori Imperiali in Rome and never realized,” which “was meant to be a metaphor for Alighieri’s work”: with these words, Luigi Gallo, director of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino and curator, together with Luca Molinari and Federica Rasenti, of the exhibition City of God. City of Men. Dante’s Architectures and Urban Utopias (at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche from Nov. 26, 2021 to March 27, 2022) succinctly summarizes the project of the Danteum, the sumptuous building conceived by architects Pietro Lingeri (Bolvedro, 1894 - 1968) and Giuseppe Terragni (Meda, 1904 - 1943) to celebrate Dante Alighieri, and yet which would never come to life.

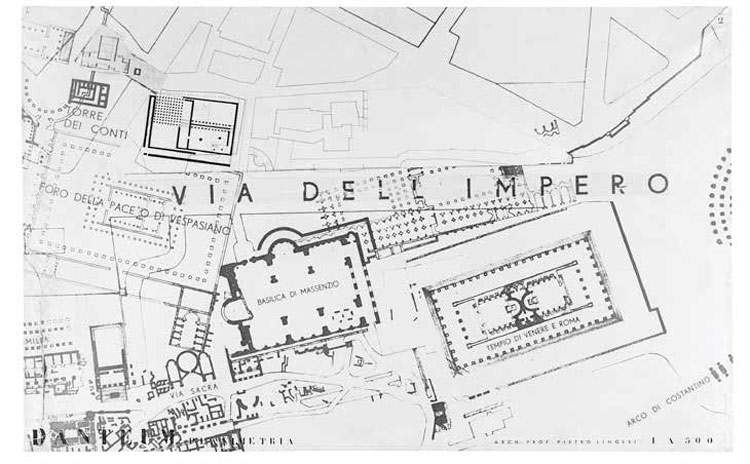

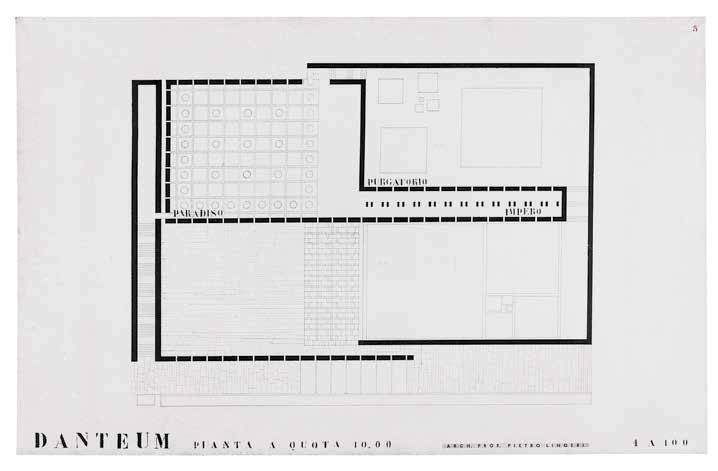

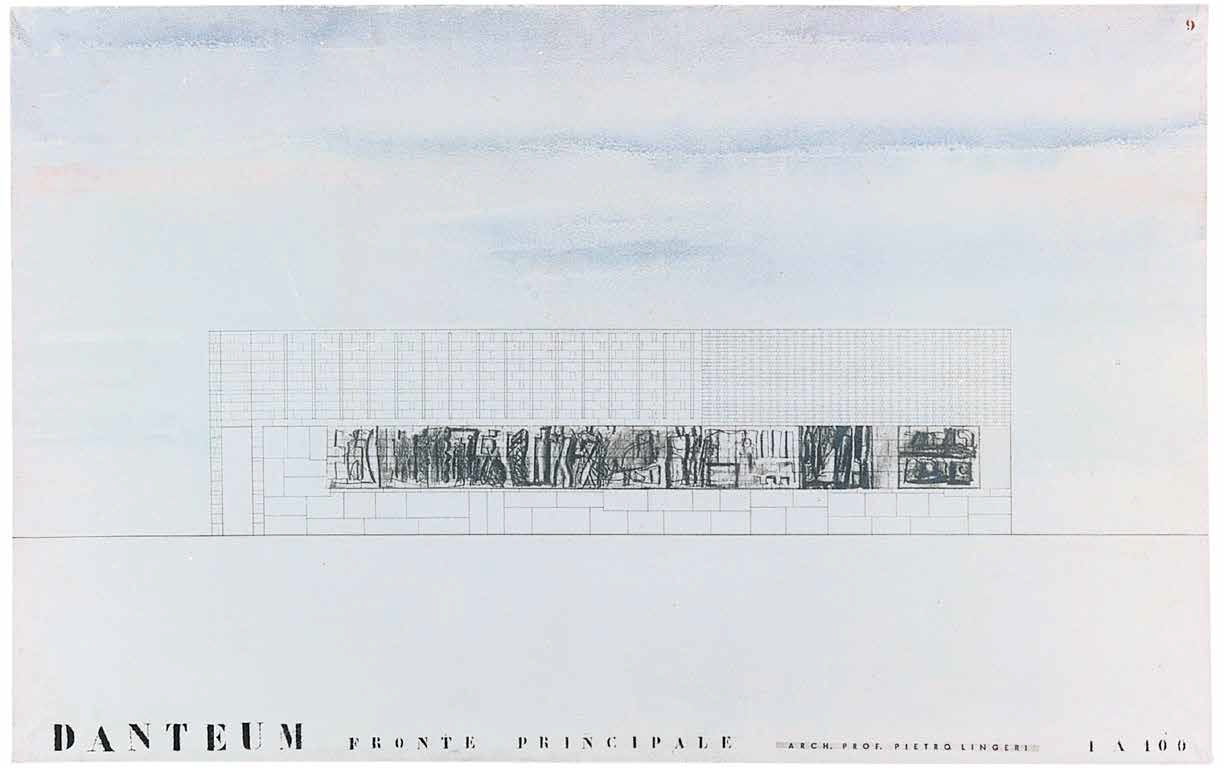

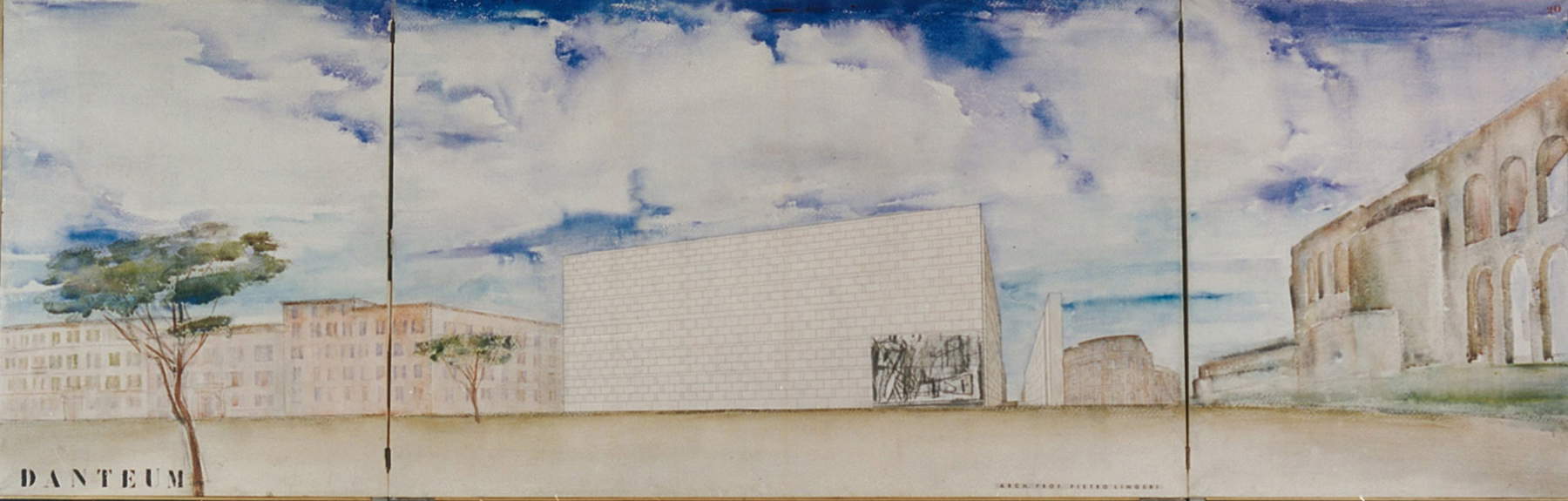

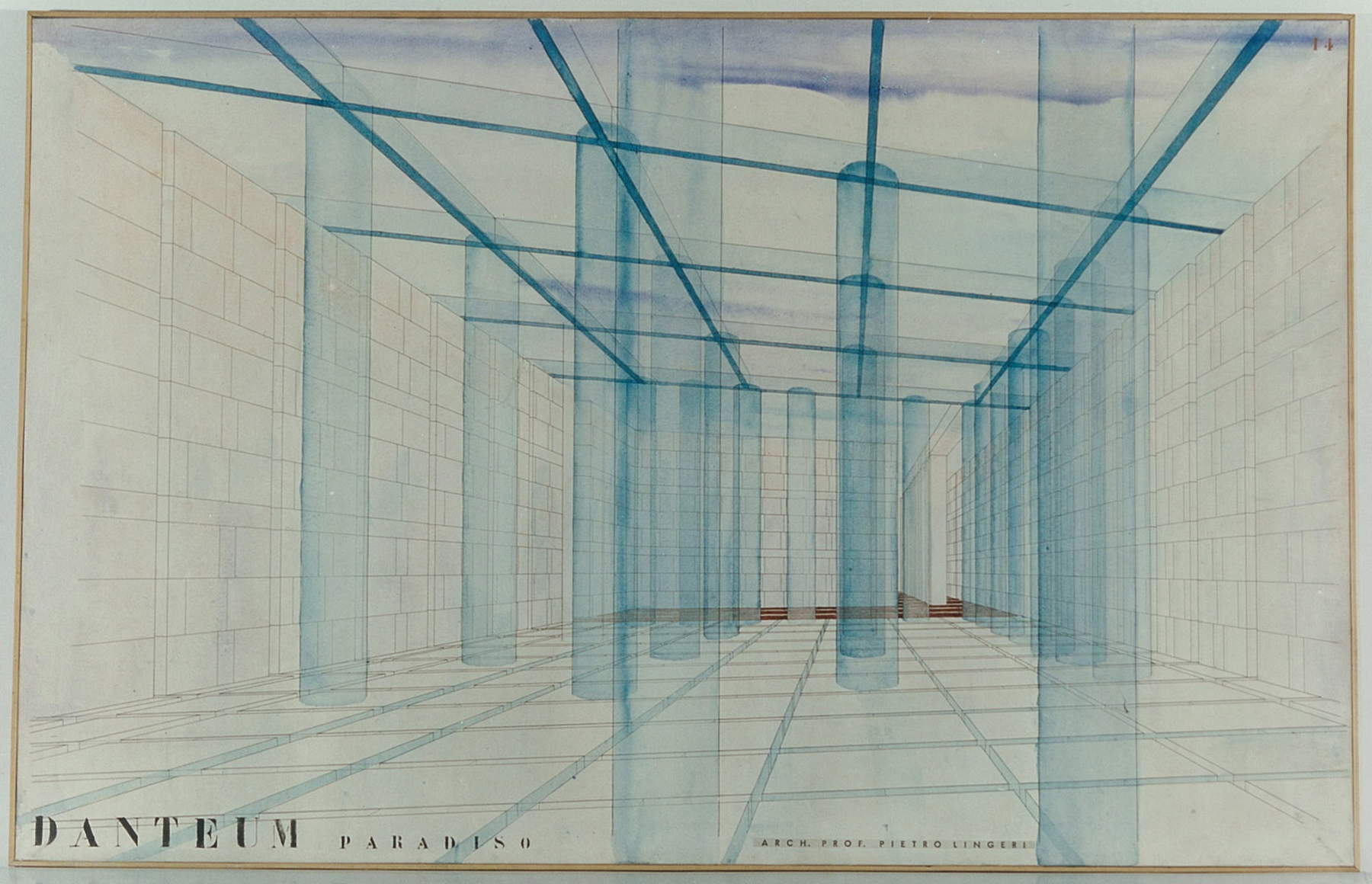

The idea had come to Rino Valdameri, director of the Brera Academy as well as president of the Italian Dante Society, who proposed it in November 1938 to the Mussolini government. A site had also been identified for the Danteum, a plot of land along what was then Via dell’Impero (now Via dei Fori Imperiali), which had already been identified for the 1934 Palazzo Littorio competition. The choice of site was strategic: the Danteum would in fact be built near the buildings of ancient and medieval Rome, placing itself, writes Luigi Gallo again, “as a symbolic hinge between past and present.” Benito Mussolini expressed appreciation for the project, which even in form was to recall the Divine Comedy, with rooms inspired by the three canticles (Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise) arranged along an ascending helicoidal path, and shaped by the poetic use of light, through materials that were to enhance the nature, function and suggestions of the individual rooms (for example, for Paradise, Lingeri and Terragni had imagined a transparent roof supported by crystal columns). The floor plan itself, based on the Golden Rectangle, was inspired by antiquity, with a major side identical in size to the minor side of the nearby Basilica of Maxentius: “it was a matter,” Gallo explains, “of fixing, through geometric forms, the relationship between the monumental scale of the marble building, related to the volumes of the classical ruins, and the esoteric Dantean path enclosed in the walls, devoid of openings to the outside, which seem to slip moon over moon. The purpose was fully symbolic: less than a third of the total area of the project, in fact, had a practical function, related to the exhibition rooms and the library. However, the interest in the metrics of the volumes, the concatenation of the rooms, the play of light and the use of innovative materials, return the authors’ thoughts on the form, on the specific function of a monument that, if realized, would have been one of the greatest achievements of the twentieth century.”

The Danteum was, in essence, a highly innovative project, the impact of which was returned in its entirety by the Urbino exhibition, which, for the first time, displayed the original materials of Lingeri and Terragni’s project, preserved in theLingeri Archive in Milan, in their entirety, and in dialogue with one of the masterpieces of the permanent collection of the Ducal Palace, the Ideal City, a painting symbolic of the Renaissance, of which we do not know the author. The Danteum was also a kind of ideal building: first, it was an unprecedented fact that architecture was called upon to give form to Dante’s imagery. Then, the language that was to support the building was also something never attempted before: it was in fact a matter of reconciling the demands of the avant-garde of architecture with, on the one hand, the celebratory needs of the fascist regime and, on the other, those required by the representation, in architectural forms, of Dante Alighieri’s repertoire. To use Federica Rasenti’s words, “anarchitecture born from the imaginary, the slab of Dante’s poem brought back to mathematics and geometry.”

The goal of the two architects, as Giuseppe Terragni himself had occasion to summarize in the report accompanying the project, was to “imagine and translate into stone an architectural organism that through the balanced proportions of its walls, its halls, its ramps, its staircases, its ceilings, the changing play of light and sunlight, which penetrates from above, can give those who walk through the interior spaces the feeling of contemplative isolation of abstraction from the outside world permeated with too much noisy liveliness and feverish anxiety of movement and traffic.” To give form to the Danteum, which for Terragni was a “plastic fact of absolute value bound to the characters of Dante’s composition,” the two architects imagined a scheme capable of making the architectural monument adhere to the literary work by making the two entities (“spiritual facts,” in Terragni’s report) share in an armionous way: and this coexistence, for the designers, would only be possible by setting the building according to the division of symbolic numbers such as 1, 3, 7, 10 and their combinations. This also explains the choice of the Golden Rectangle, so defined because its sides are in a golden ratio to each other (the smaller side is equal to the proportional middle segment between the larger side and the segment that results from the difference of the two sides): this geometric form can moreover be broken down into a square and another golden rectangle. Moreover, Terragni went on to explain, this was a shape widely used in antiquity (particularly by Assyrians, Egyptians and Romans): the example of the Basilica of Maxentius, which was also set on a plan coinciding with a golden rectangle, was there to prove it.

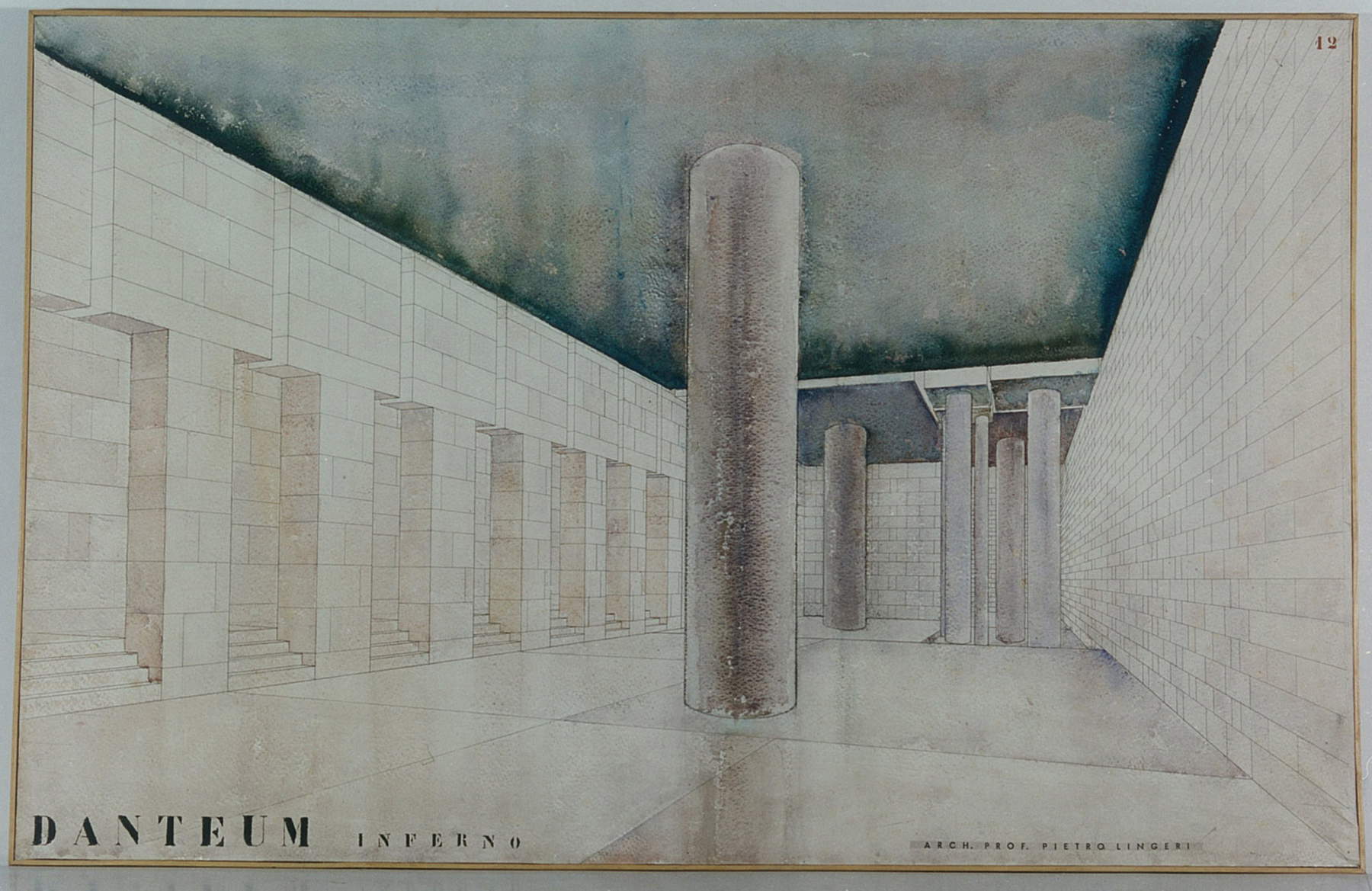

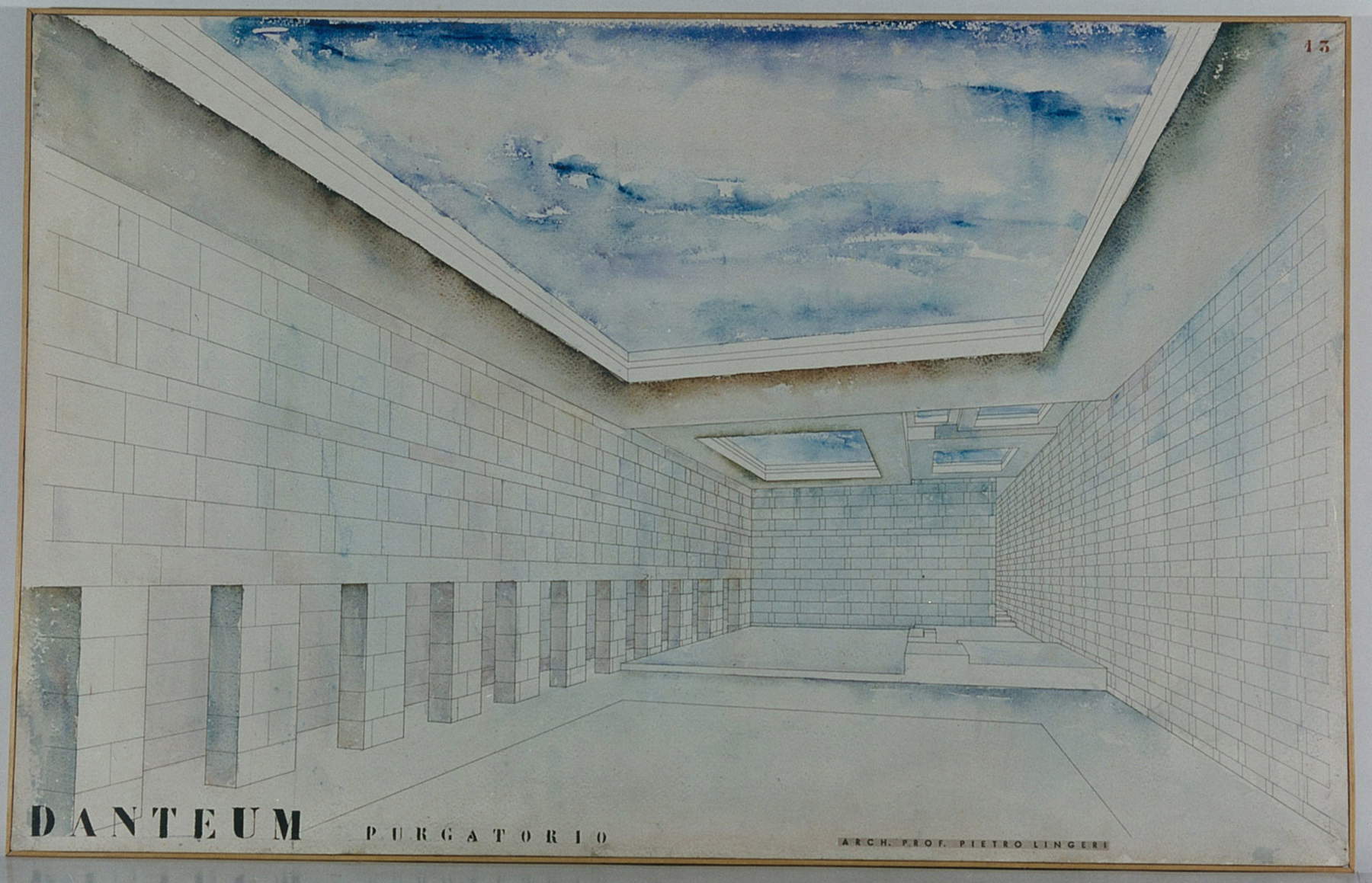

Translating Dante’s imagery into numerical laws, however, was not enough to transform the Divine Comedy into architecture: it was also necessary to suggest to the visitor the sensation of passing through the three places of Dante’s afterlife. Thus, for example, for the Inferno, it would have been necessary, the report goes on to say, “an atmosphere that would suggest to the visitor and seem to weigh down even physically on his mortal person and move him in the same way that the ’journey’ moved Dante in contemplating the misfortune of the punishments of the sinners whom in the sad pilgrimage he was gradually encountering.” Terragni recognized, however, that describing such a state of mind had already been difficult for Dante with words: with the means of architecture the task would be even more arduous. So, with visionary genius, Terragni and Lingeri thought of using the possibilities offered by geometry to seek the essentiality of Dante’s places: a dense colonnade takes us into the dark forest, an empty and heavy architecture supports the hall of hell, a room of solids with openings to the sky informs purgatory, an airy and bright hall takes the visitor into paradise. “Achieving the maximum of expression with the minimum of rhetoric, the maximum of emotion with the minimum of decorative or symbolic adjectification,” the two architects wrote. “It is a great symphony to be realized with primordial instruments.”

The Danteum was to be a kind of temple, surrounded by mighty walls, with a very studied spatial organization: even the elevations are all different and based on multiples of three (2.70 meters for hell, 5.40 for purgatory and 8.10 for heaven). Thus, recalling the canticles only with the building elements, which for Terragni “are the basis, the alphabet with which an architect can compose more or less harmoniously.” Larchitecture, according to the great architect, “is not construction or even the satisfaction of needs of a material order; it is something more; it is the force that disciplines these constructive and utilitarian gifts to an end of much higher aesthetic value. When that ’harmony’ of proportions has been achieved which induces the observer’s soul to pause in contemplation, or in emotion, only then will the constructive scheme be superimposed on a work of architecture.”

The building designed by Terragni and Lingeri, Rasenti further explains, “unfolds through an obligatory path, at once ascending and symbolic, that leads to the gradual discovery of the various spatial sequences placed at different heights. The visit through the halls starts from the street and leads back to it; the entrance breaks the Danteum’s introversion by creating a kind of gap between two straight lines, which opens through the high walls. Tracing the Dante poem, the discovery of the building takes place through the dark forest, a space dominated by the presence of a hundred columns, here the dense colonnade is contrasted with a wide contiguous courtyard, which anticipates and opposes it, evocatively, through the void.” The great protagonist of the building is light, which has the task of marking out the space: in the Inferno room, a few glimmers of light contribute, Rasenti further emphasizes, to “create the atmosphere of suspension and emphasize the presence of the seven monolithic columns of different thicknesses that define the space, while supporting the different portions of the ceiling, which is also composed of seven blocks.” Moving from Hell to Purgatory, the seven ceiling portions of Hell become openings to heaven, coveted by sinners who are atoning for their punishments while waiting to ascend to Heaven, where visitors would find a glass roof supported by crystal columns, to have a clear view of the vault of heaven. A walk through rooms that had no practical purpose, were not tied to any function other than the re-enactment of the Supreme Poet’s journey.

The goal of the fascist regime was, of course, propagandistic in nature: in the Statute prepared by Valdameri, the proposal was to erect in this era, in which the will and genius of the Duce are realizing the imperial dream of Dante, a temple to the greatest poet of the Italians, which would implement celebrations of Dante’s word, considered the prime source of Mussolini’s great creation, where there would also be a complete of everything that could be of use to scholars of Dante, and which would contribute to “suggest and help all those initiatives that foment and attest to the imperial character of Fascist Italy.”

Before the Urbino exhibition, only three people were able to see all the plates of the project together: the two authors, and Benito Mussolini. The Palazzo Ducale exhibition therefore opened the complete corpus of sheets for the Danteum to multiple eyes. Terragni and Lingeri’s project, as anticipated, would never see the light of day: at the end of 1939 it was definitively shelved due to changed political conditions and especially in view ofItaly’s wartime commitment, which shortly thereafter, on June 10, 1940, would enter the war alongside Germany, against France and Great Britain. The Danteum would thus remain represented, Rasenti explains, “only on paper, in a corpus of about thirty watercolor plates and drawings, accompanied by the model, the descriptive report and the estimated metric calculation.” Yet, even if it remained only on paper, the Danteum cannot but be considered, for the innovative and visionary characters that animate the project, one of the icons of Italian modernism.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.