Ten things to know about Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin is undoubtedly one of the most influential and controversial artists on the contemporary scene, capable of transforming her life into art with a raw, direct and deeply emotional language. Born in Croydon, England, in 1963 and raised in the coastal town of Margate, Emin has been able to channel personal experiences-often painful-into works that span painting, sculpture, installation, video and neon. Many of these are on display at the exhibition Tracey Emin. Sex and solitude, in Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, from March 16 to July 2025, the largest exhibition ever held in Italy on the artist.

Her art practice is inherently autobiographical: themes such as the body, sexuality, love, loneliness and trauma emerge powerfully in each of her works. Emin does not simply depict specific events in her life, but transforms universal emotions such as passion and melancholy into powerful visual metaphors. Tracey Emin’s career is studded with celebrated works that have shaped art in recent years. From intimate embroideries to the use of neon for phrases that mimic her handwriting to monumental bronze sculptures, each piece tells a personal story that becomes universal. Emin has also been a central figure in the Young British Artists (YBA) movement, standing out for her innovative and provocative approach. With a constant dialogue between vulnerability and strength, her art explores the limits of figuration and abstraction, relating to masters such as Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele.

Here are ten things to know about Tracey Emin to better understand her artistic universe.

1. Tracey Emin had a turbulent childhood

Tracey Karima Emin was born on July 13, 1963, in Croydon to a Turkish Cypriot father and an English mother of Romnichal descent, a Roma group settled in the United Kingdom beginning in the 16th century. He grew up in Margate, a coastal town in Kent, where he experienced a childhood marked by economic hardship and personal trauma. Margate, with its windswept beaches and decadent charm, leaves an indelible imprint on the artist’s imagination. At the age of thirteen, he underwent an experience of sexual violence that would profoundly influence his art. This traumatic event becomes one of the interpretive keys to her artistic production: the wounded but resilient female body emerges as a central theme in her works.

At fifteen, Tracey ran away from home, beginning a life path marked by rebellion and self-determination. Running away represents not only a break with her family environment but also a first step toward building her own artistic identity. Margate nevertheless remains a symbolic place for Emin: years later he would return there to open TKE Studios, a space dedicated to emerging artists. This deep connection to his roots shows how his turbulent childhood was not only a source of suffering but also of creative inspiration.

2. Her artistic training was extremely rich

Tracey Emin’s artistic training is characterized by a nonlinear but extremely rich path of experiences. After initially studying fashion at Medway College of Design, she abandoned this field to pursue visual art at Sir John Cass School of Art. She then graduated in fine arts from Maidstone College of Art and continued her studies at the prestigious Royal College of Art in London, where she specialized in painting in 1989 with a thesis dedicated to her idol Edvard Munch.

However, Emin’s painting career came to an abrupt halt in the 1990s due to two traumatic miscarriages that deeply marked his personal and artistic life. The artist then decided to destroy most of his earlier pictorial works and temporarily abandoned this medium to explore other forms of expression such as embroidery, installations and videos. This phase represents a crucial moment in his creative evolution: the abandonment of painting is not a definitive renunciation but rather a necessary pause to rework his artistic language.

During this period Emin creates emblematic works such as Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, a curtain embroidered with the names of the people with whom he had shared a bed (in both a literal and metaphorical sense). This work marks the beginning of his international fame and demonstrates how the artist is able to transform intimate experiences into powerful artistic statements.

3. His first masterpiece is Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995.

The work Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 is one of Tracey Emin’s most discussed and significant creations, a work that embodies her autobiographical aesthetic and her ability to transform personal intimacy into art. Made in 1995, the work consisted of a blue-colored camping tent, purchased in a military store, on which Emin had stitched with the appliqué technique the names of all the people with whom she had shared a bed from her birth until that moment. Importantly, the title of the work is often misunderstood: “slept with” does not refer exclusively to sexual relations, but includes anyone who simply slept in the same bed with her, including family members, friends and lovers.

The tent, then, became a symbolic place, a kind of intimate sanctuary that contained the artist’s memories and relationships. Names were stitched with different colored threads, creating a visual patchwork that reflected the complexity and variety of her experiences. The interior of the tent was illuminated, inviting the viewer to physically enter the space and engage with Emin’s personal history. The work raised questions about the concept of intimacy, female sexuality, and the relationship between art and life.

The choice to use a camping tent was not accidental: the tent is a place of temporary refuge, a shelter from external reality. Likewise, Emin’s work offered an intimate look at her life, revealing vulnerability and fragility. Moreover, the tent evokes the idea of nomadism and travel, suggesting an ever-evolving existential path.

Unfortunately, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 was destroyed in a fire in 2004, when a warehouse in London where it was stored caught fire. The loss of the work was a major blow to Emin, who considered the tent a key piece of his personal and artistic history. Despite its destruction, and although Emin has repeatedly stated that she has no intention of redoing it, the work continues to live on in the public imagination as a symbol of her art.

4. My Bed: Tracy Emin’s bed becomes the work of her consecration

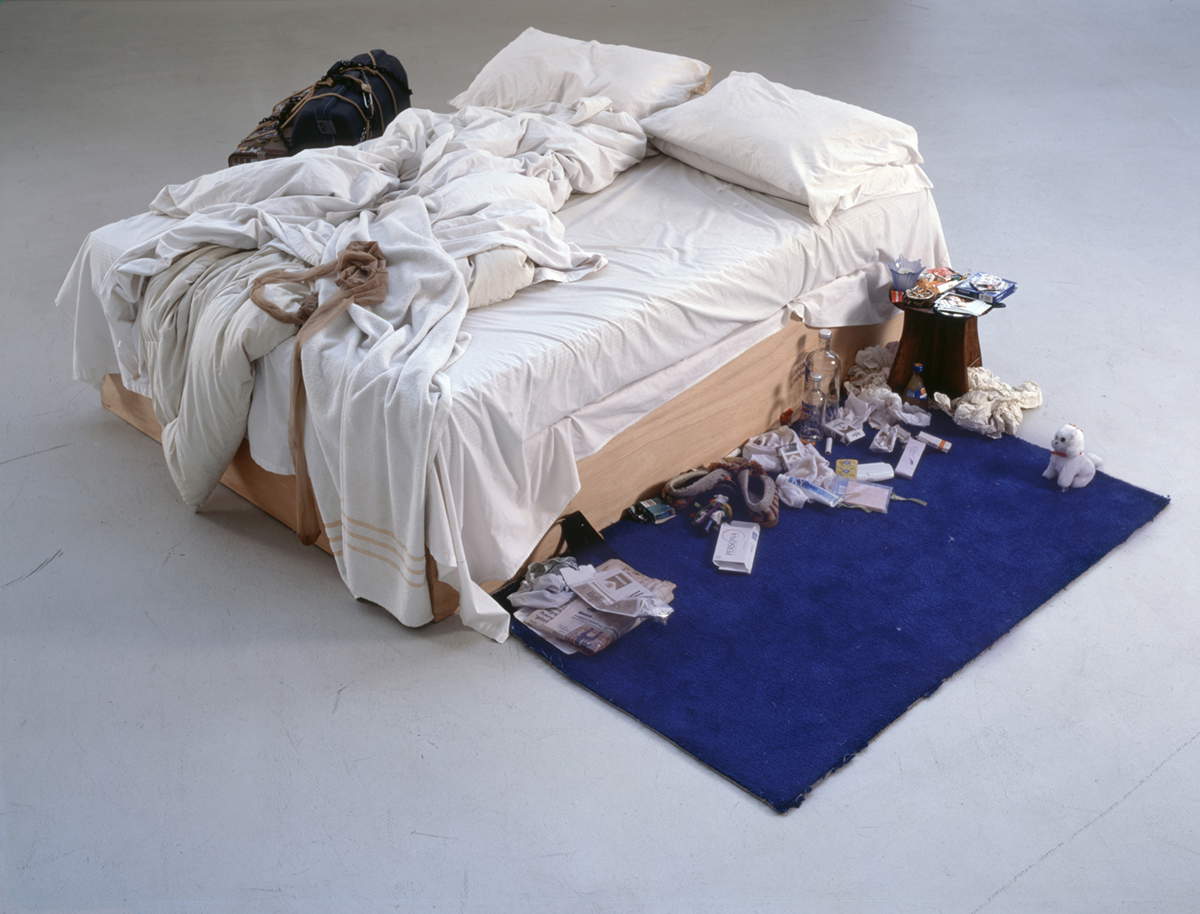

In 1998 Tracey Emin presented My Bed, perhaps the most celebrated work of her career. It is an unfiltered depiction of the artist’s bed during a particularly difficult period in her life, characterized by depression and alcohol abuse. The work includes stained sheets, empty bottles, cigarette packs, and personal items such as soiled underwear - details that tell a story of human vulnerability with disarming sincerity. Exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1999 as a Turner Prize nominee, My Bed elicits mixed reactions: on the one hand it is praised for its emotional authenticity; on the other it is criticized by those who do not consider it “art.” Despite the controversy, the work establishes Tracey Emin as one of the most original voices in contemporary art.

However, My Bed is not only an autobiographical work: it also represents a universal reflection on the human condition. The bed becomes a metaphor for the place where crucial moments of life - birth, death, love and suffering - are consumed, transforming itself into a powerful symbol of existence itself.

5. Tracey Emin often uses neon in her practice.

One of the distinctive elements of Tracey Emin’s art practice is her use of neon to create textual works that mimic her handwriting. This medium allows her to transform intimate thoughts into powerful and evocative visual statements. Neon phrases are often short but charged with emotional meaning: 2010’s I Never Stopped Loving You , dedicated to the town of Margate, or 2009’s Those Who Suffer LOVE are emblematic examples, as is Sex and Solitude, created for the Florence exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi (2025).

For Emin, neon represents an expressive medium capable of combining fragility and strength: the bright lights draw the viewer’s gaze while the words reveal painful truths or intimate confessions. Moreover, the use of handwriting gives the works a personal character that contrasts with the technological coldness of the material. The neon phrases are never mere slogans but poetic fragments that invite the viewer to reflect on his or her own emotional experience. In this sense, neon becomes a tool for creating deep connections between the artist and the audience. “I grew up surrounded by neon-they were everywhere in Margate,” said Tracey Emin. “There are only a few left there today, but in the rest of the world there are so many. I started making them because I wanted to see more of them around. And you know how it is, you have to be careful about your desires. Real neon contains gases like argon and neon precisely, which have a positive effect on mood because they radiate energy. That’s why they were used in casinos, brothels, bars, clubs, and so on. Neon is pulsating light and energy, it is a living thing, and that makes me feel good. Neon, as an object, is just beautiful and makes you feel good. That’s why I made them and continue to make them.”

6. Tracey Emin admires the art of Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele.

Tracey Emin has always declared a deep admiration for artists such as Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele, from whom she draws inspiration both technically and thematically. Like them, Emin explores themes related to human vulnerability through intense representations of the body and emotions.

In 1990, his thesis for the Royal College of Art in London was titled My Man Munch. She then dedicated a video tribute to Munch in 1998, entitled Homage to Edvard Munch and all my dead children, made on the Oslo Fjord: in the video, Tracey Emin, naked and in a fetal position on the pier located near Munch’s house, lifted her head, emitting a throaty scream, a lament for her unborn children, and a response to Munch’sScream . Again, in 2021 he created the sculpture The Mother for the new Munchmuseet in Oslo, to pay tribute to his and Munch’s mother. In 2015, the artist curated an exhibition at the Leopold Museum in Vienna entitled Tracey Emin | Egon Schiele: Where I Want to Go, creating a dialogue between her works and those of the Austrian master. These projects demonstrate how much Emin sees himself as part of an artistic tradition that focuses on the human experience in its emotional complexity.

“When I was attending the Royal College of Art,” he recalled in an interview with Arturo Galansino, “I used to take a bus from Elephant and Castle to Westminster and from there by tube to South Kensington. Sometimes, however, I would stay on the bus and get off at the National Gallery. As soon as I got in, I would go straight downstairs and there I would draw icons or just look around and take notes. I think I did that a couple of times a week for two years, and that’s what I owe my knowledge of painting and art history to. Everything I knew before then was related to Expressionism and European art from before the war; suddenly I was catapulted into another world, I understood the classics and their ideas. It was like an expansion of the mind. So Munch was pre-National Gallery while Renaissance and classical painting came through the National Gallery. And I learned them on my own, because I never really studied art history, I just delved into the art I liked.”

7. Performance as exorcism

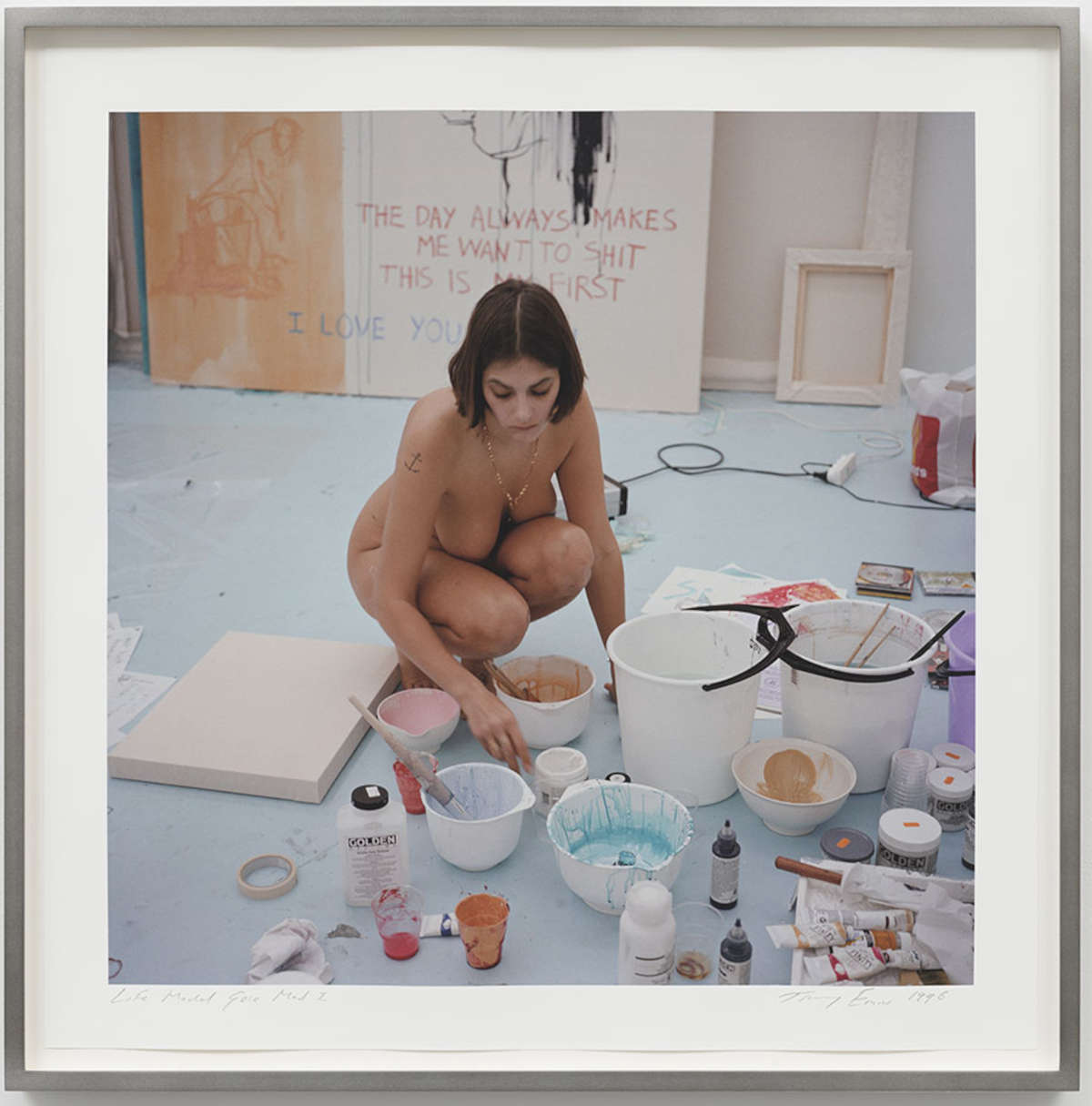

In 1996 Tracey Emin made one of her most significant works, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (“Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made”). This performance represents a turning point in her career, marking her return to painting after years of neglect. The work consists of a performance lasting three and a half weeks, during which the artist lives and works nude in a temporary studio set up as an installation. The space is accessible to the public, who can watch Emin as she creates drawings and paintings inspired by great male figures in art such as Egon Schiele, Yves Klein and Pablo Picasso.

Emin’s nudity is not only physical but also emotional: the artist exposes himself completely, transforming his own body into the subject and object of the work. This act subverts the traditional role of women in art, historically relegated to passive muse or model. Instead, Emin becomes an active protagonist of her artistic narrative, exorcising personal demons and cultural conventions that limit female representation.

The installation documents not only the creative process but also a moment of radical introspection. The artist uses painting as a means to reconnect with herself and her past, transforming an intimate experience into a universal reflection on the role of art as a tool for healing and self-affirmation. This work remains a milestone in her career and a powerful example of Emin’s ability to inextricably intertwine life and art.

8. Painting is a visceral language for Tracey Emin

Painting occupies a central place in Tracey Emin’s multifaceted artistic production, and is one of the expressive means through which the artist explores her most cherished themes: the body, sexuality, love, loneliness and pain. Although Emin is also known for her installations, embroidery and neon, painting remains a fundamental anchor in her practice, a place where the artist can give free rein to her emotions and transform personal experiences into powerful and evocative images. “For me,” the artist said, “painting is about the very essence of creativity, it is close to the divine, it is a world apart, it is like entering another dimension, another space, something that is not human.”

Emin’s painting is characterized by an instinctive, gestural approach. The artist works directly on the canvas, without preparatory drawings, letting shapes and figures emerge spontaneously. The brushstrokes are rapid and energetic, the drips of color create effects of movement and instability, and the marks left by the painterly gesture testify to the creative process. This approach reflects his desire to capture the immediacy of emotions and translate them into visual images. His canvases are often marked by a strong materiality: overlapping layers of color create thickness and texture, the surfaces are irregular and imperfect. This predilection for materiality reflects Emin’s interest in the human body, depicted crudely and realistically, with all its imperfections and vulnerabilities.

Figuration and abstraction merge in his works, creating a dynamic balance between representation and suggestion. Sometimes the figures emerge clearly from the canvas, other times they dissolve in a swirl of color. The artist thus manages to evoke complex and ambiguous emotions, leaving the viewer free to interpret the work. Colors also assume a key role in Emin’s painting. The artist uses bold and contrasting colors, creating intense and vibrant atmospheres. Red, black, blue and white are the predominant colors in his canvases, often used to express passion, pain, anger and melancholy. Among the most significant works in her painting production are Hurt Heart (2015), It was all too Much (2018), It - didnt stop - I didnt stop (2019), There was blood (2022), Not Fuckable (2024) and I waited so Long (2022). These paintings testify to Emin’s ability to create a powerful and personal visual language capable of touching the deepest chords of the human soul

9. Love is a central theme in Tracey Emin’s art

Love is one of the most recurring themes in Tracey Emin’s work, explored in its many facets: desire, romance, loss, grief, sexuality. For Emin,love is never represented in an idealized way but always in its emotional complexity, often intertwined with painful personal experiences. Works such as I Want My Time With You (2017), installed in London’s St Pancras International train station, translate the emotional intensity of love into powerful visual statements. This neon sculpture sits in a symbolic place for daily meetings and goodbyes, amplifying the universal meaning of the message.

Emin’s embroideries also address the theme of love with a delicacy that contrasts with the intensity of the emotions depicted. Works such as No Distance (2016) use materials traditionally associated with women’s craft to explore deeply personal feelings. In this way, the artist subverts cultural conventions associated with gender roles, transforming “domestic” techniques into powerful expressive tools.

Love also emerges in the monumental bronze sculptures made by Emin in recent years. These works combine vulnerability and eroticism to explore the human body as a site of emotional and physical connection. Through these different forms of expression, Emin manages to capture the essence of love in its many contradictions: joy and suffering, intimacy and distance.

10. Tracey Emin is an important female voice in art history

Tracey Emin is now recognized as one of the most influential artists on the contemporary scene, but her path to international success has not been without obstacles. After achieving notoriety in the 1990s through her participation in the Young British Artists (YBA) movement, Emin has continued to evolve artistically, earning a prominent place in the global art world. In 1999 his work My Bed was nominated for the Turner Prize: although he did not win, the work sparked a huge media debate that helped solidify his reputation. In 2007 Emin represented Britain at the Venice Biennale with the exhibition Borrowed Light: this event marked the official recognition of his contribution to contemporary art by British institutions. In the following years, Emin received numerous awards and honors. In 2011 she was appointed Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy of Arts, becoming the second woman to hold this position in the history of the institution. Her work has been exhibited in some of the world’s most prestigious institutions, including MoMA in New York, the Louvre in Paris, and the Munch Museum in Oslo. Despite her global success, Emin remains deeply attached to her British roots, continuing to work between London and Margate.

The British artist thus stands as a symbolic figure in the struggle for the affirmation of women in contemporary art. From the very beginning of her career, she has challenged traditional conventions that relegate women artists to secondary or marginalized roles. Through works that interweave autobiography and personal confession, Emin becomes an active protagonist of her own artistic narrative. She is also a committed artist. Indeed, in 2022 Tracey Emin opened the Tracey Karima Emin Studios (TKE Studios) in Margate, an ambitious project that reflects her commitment to supporting the next generation of artists. The studios offer free residencies to emerging artists selected through a rigorous application process. This space is not only a physical place but also a creative community where artists can develop their ideas in a stimulating and collaborative environment.

The project also includes the Tracey Emin Artist Residency (TEAR), a free program that offers hands-on training and professional support to participating artists. This initiative demonstrates Emin’s commitment to giving something back to the art world that has given her so much. For the artist, TKE Studios represents a kind of return to her roots: Margate is not only the place of her childhood but also an inexhaustible source of inspiration. In addition to artist studios, TKE Studios hosts exhibitions and events open to the public, creating a bridge between emerging artists and the local community. This project emphasizes the importance of accessibility in art and reflects Emin’s vision as a socially engaged artist.

“Art,” argues Tracey Emin, “should always be about what is true for you as an individual, always. It should be sincere and arise from a genuine desire to find your own answers. At least, that’s how it is for me. For a long time my work was absolutely unfashionable. But I didn’t care, because I knew it was the right thing for me.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.