Ten things to know about Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, important Portuguese painter of the 20th century

Portuguese artist Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (Lisbon, 1908 - Paris, 1992) was an enigmatic and multifaceted figure in the 20th-century art scene, rediscovered in Italy in 2025, just over 30 years after her death, with an exhibition at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice (April 12 to September 15, 2025, curated by Flavia Frigeri). An artist trained in the tradition of her country, Portugal, she was nevertheless steeped in Italian art and also looked to the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, above all Cubism and Futurism, and to figures such as Picasso, Matisse, and Cézanne. The complexity of his interests is reflected in his visual vocabulary, which mixes form, color, and perspective to explore the ambivalence between the real and the imaginary, often resorting to abstract environments and optical illusions.

Her seemingly simple life concealed an absolute dedication to art, an unwavering commitment that accompanied her from her first oil painting at the age of thirteen until her passing. In her works, Vieira da Silva transfused everything she knew, experimented with, and imagined: from stacks of books in libraries to dancing harlequins, from construction site scaffolding to cityscapes, to the anatomy of space itself. This article aims to outline an in-depth portrait of this extraordinary artist, analyzing the influences that shaped her path, her working method and the recurring themes in her work, thus revealing the anatomy of a space that is both interior and exterior.

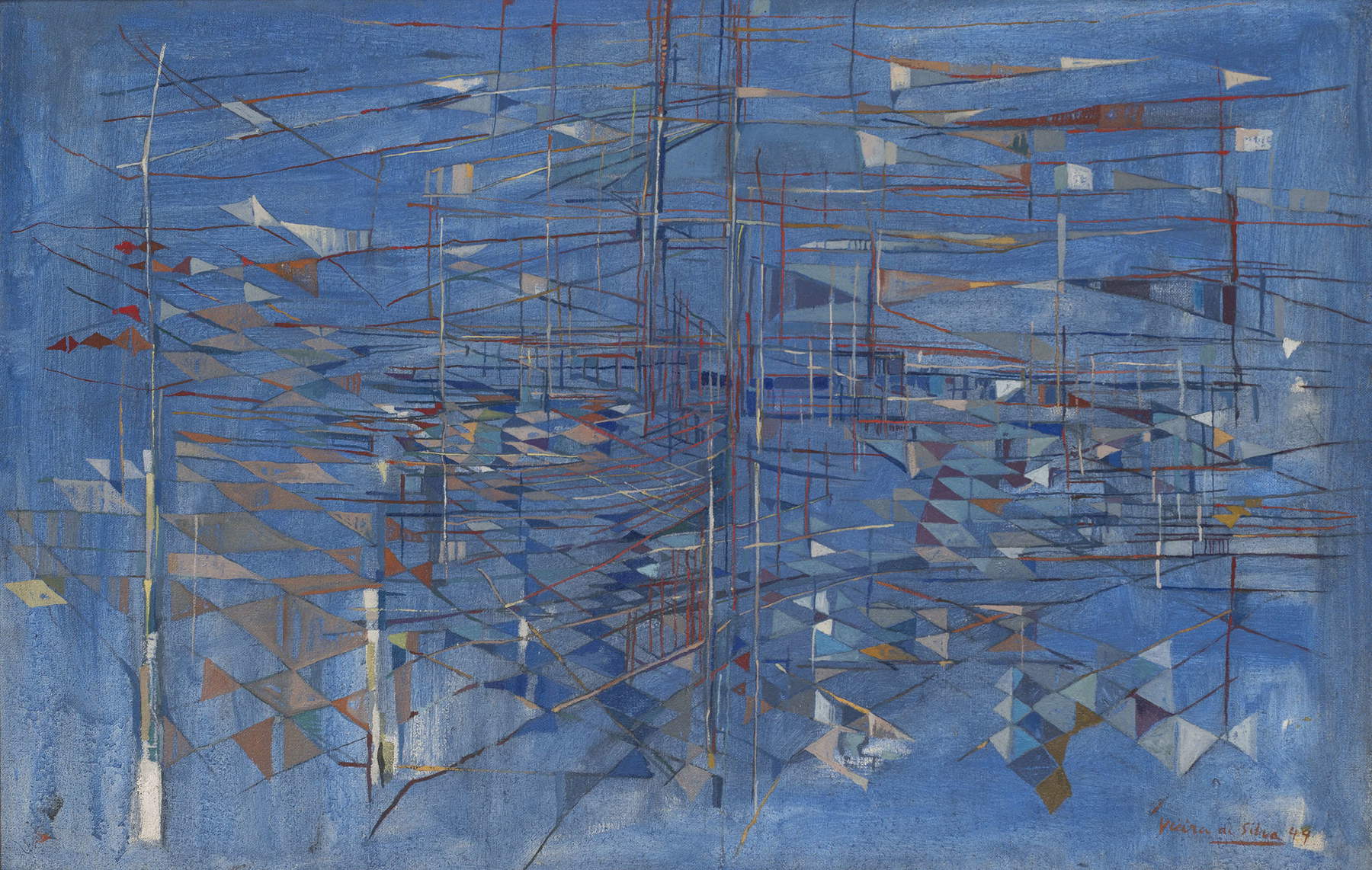

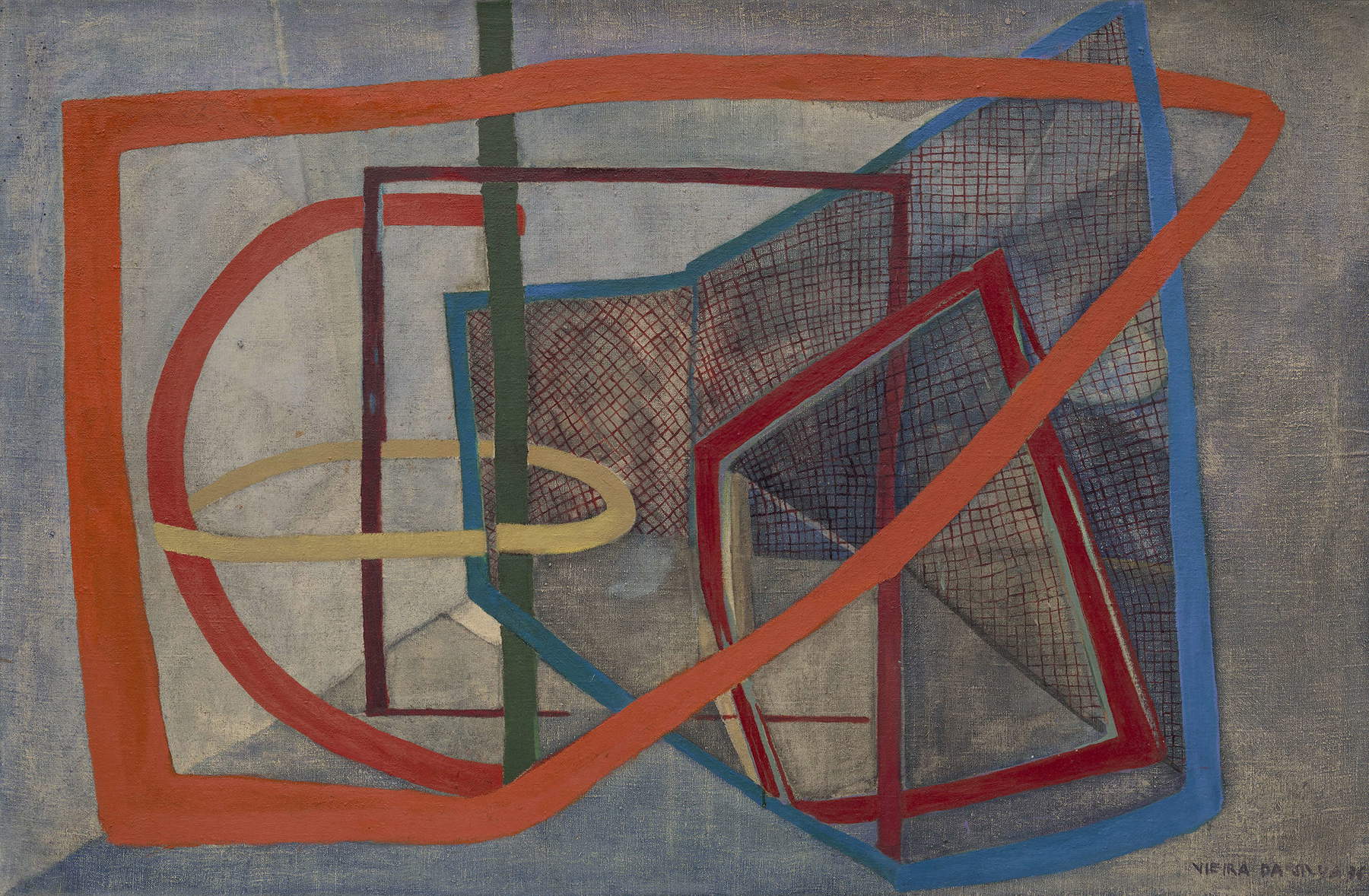

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva developed a unique and recognizable style characterized by a profound exploration of space and perspective. Her works are not limited to the representation of objects or figures, but seek to make visible the anatomy of space itself, breaking it down and recomposing it into geometric and abstract forms (this is the underlying theme of the Venetian exhibition). One of the distinctive elements of his style is the use of complex, layered perspective, which creates a sense of depth and ambiguity. His canvases are often populated with “jewel-like squares” arranged side by side, generating an effect of movement and revealing dancing figures emerging from space.

Vieira da Silva was influenced by several artistic currents. However, she was able to develop a personal and original language that made her a prominent figure in the 20th century European abstract art scene. Her style is a dialogue between order and chaos, between structure and movement, reflecting the complexity of reality and human experience. An artist, however, little known in Italy: so here are ten things to know about Maria Helena Vieira da Silva to learn more about this singular figure.

1. She had a seemingly simple, but culturally dense and lonely life

Born in Lisbon into an affluent and culturally stimulated family, Vieira da Silva received a private upbringing that led her to spend many hours in solitude during her childhood. “I never got to know other children,” she had to say. “Sometimes I was completely alone; sometimes I was sad, even very sad. I would take refuge in the world of colors, in the world of sounds. I think all these influences merged into one entity, inside me.” This condition, although sometimes a source of sadness, was a valuable resource for her: solitude allowed her to develop a rich inner world. Her education was strongly influenced by her family environment, which encouraged her to cultivate a passion for art, music and literature.

The painter herself called her life “seemingly simple,” but this simplicity concealed a complexity of deep reflection and intense creative activity. Her solitary upbringing contributed to making her a reserved person, but also capable of great concentration and dedication to artistic work. Her sensibility was nurtured by readings, classical music and travel, elements that merged into a single entity within her, fueling her imagination and her ability to translate the most subtle and complex emotions into painting.

2. He owes a deep debt of to Italian art.

In 1928, early in her career, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva undertook a seminal trip to Italy that profoundly influenced her artistic vision. She visited cities rich in history and art such as Milan, Padua, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Pistoia, Pisa, and Genoa, where she devoted herself to quick sketches and annotations, showing a keen and immediate interest in the frescoes and works of the 14th and 15th centuries. For her, these masterpieces represented the dawn of modernity and offered her a solid basis for understanding perspective, composition, and spatiality. In particular, Paolo Uccello’s work, with its innovative vertical perspective and dynamic construction of space, left an indelible imprint on her understanding of depth and pictorial structure. “Vieira da Silva was so impressed by the triptych of the Battle of San Romano,” writes scholar Jennifer Sliwka, “that when, a decade after completing her studies in Florence and Paris, she was in search of visual models to compose works on the atrocities of World War II she returned to those compositions, where the laws of perspective seemed to be employed in an attempt to bring order to the chaos of battle.”

This trip was a time of intensive training that allowed her to connect the Renaissance tradition with modern experimentation, laying the foundation for her abstract, dialectical language that she would develop in later years. Her attention to architectural details and the construction of space, as well as her ability to synthesize forms and volumes, derived largely from this immersion in Italian art, which Vieira da Silva considered an indispensable starting point for her artistic research.

3. The encounter with Paris and artistic training between sculpture and painting

At the age of nineteen, in 1928, Vieira da Silva moved to Paris, then the epicenter of the artistic avant-garde, to give a professional twist to her passion for art. She began by studying sculpture at the Académie de La Grande Chaumière, under masters such as Antoine Bourdelle and Charles Despiau, but soon turned to painting, attracted by the freedom of expression and the possibility of exploring space on canvas.

“Paris,” writes Flavia Frigeri, “not only offered Vieira da Silva a type of independent art education not readily available in Lisbon, but also immersed her in the reality of the avant-garde, which until then she had only experienced from afar. The discovery of Picasso’s work, but even more so of Henri Matisse’s colors, Pierre Bonnard’s perspective, and Paul Cézanne’s subjects and pictorial architecture, prompted her to seek out something that seemed elusive at the time and that only a few years later would materialize in a highly personal abstract language.” These artists profoundly influenced her research, prompting her to develop a language characterized bya focus on structure, perspective and color. Her Parisian training was thus a melting pot of stimuli and experimentation, allowing her to move beyond the Portuguese tradition and into the international artistic debate, while maintaining strong ties to her cultural roots and her unique vision of space.

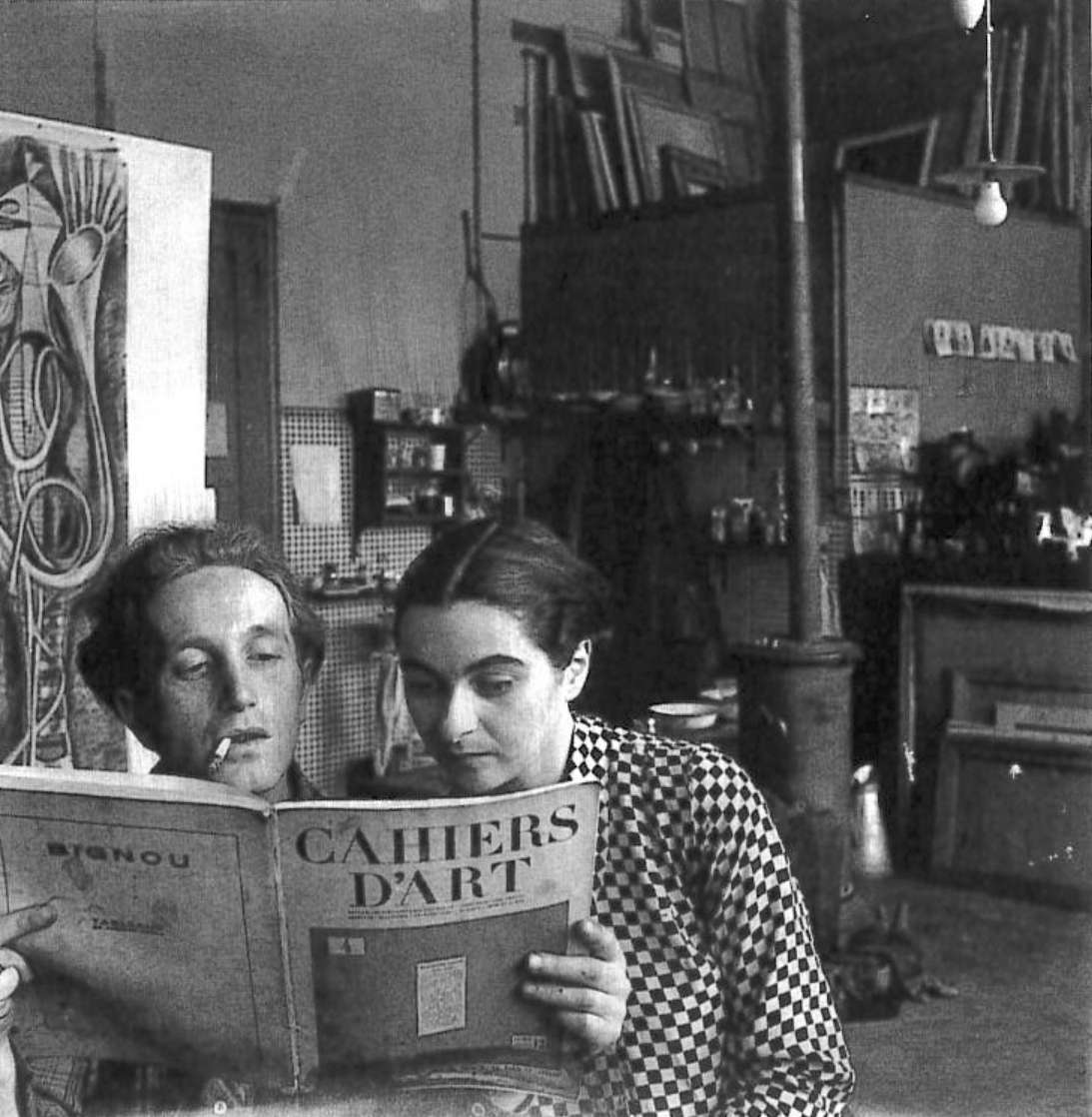

4. In her relationship with Arpad Szenes, she was the leading figure.

In 1928, shortly after her arrival in Paris, Vieira da Silva met Arpad Szenes, a Hungarian painter with whom she established a deep and lasting relationship. Their relationship, which lasted until Szenes’ death in 1985, was characterized by intense complicity, both personal and artistic.

Despite stereotypes that often relegate women to secondary roles in artist couples, it was Vieira da Silva who emerged as a prominent and independent figure. Szenes respected and admired her dedication to painting, celebrating her in the many portraits he dedicated to her as she worked. Their life together was described by her as “wonderful,” based on a total and intimate knowledge of each other. This relationship was a fundamental support for Vieira da Silva, who was thus able to devote herself completely to her art without compromise, experiencing a love that was intertwined with her passion for painting and that allowed her to maintain a prominent position in the European art scene.

5. The studio for her was not only a place of creation but also a pictorial subject

Vieira da Silva’s was not just a simple work space, but a real recurring theme in her works. In 1934-35 she made Atelier, Lisbonne, a painting that depicts the studio as essential architecture, reduced to transparent planes and minimal structures. This work testifies to his attention to the anatomy of space, influenced by architectural elements and human bone structure.

The idea of stripping the space of everything superfluous to leave only the essential framework is also found in other coeval works, where architecture becomes an exercise in synthesis and depth. The studio was a world of its own for her, a place where time dilates and where painting develops slowly, in a continuous dialogue between the artist and the canvas. The photograph taken in 1947 by Denise Colomb in her Paris studio captures this atmosphere: Vieira da Silva appears in multiple forms, as if the studio were a place of layering, of multiple presences reflecting the complexity of her art.

6. She had a curious fascination with bones

While studying in Lisbon, Vieira da Silva took a course in anatomy that led her to draw bones in all positions, an activity she deeply loved. The scapula, in particular, fascinated her as a “masterpiece” of form and structure. “I used to draw hundreds of them,” the artist wrote. “I used to draw bones in all positions, which I liked very much. I found the scapula to be a masterpiece. I used to walk around with the bones in my bag, even taking them home several times to draw them.”

Contrary to what one might think, this interest did not steer her toward figurative realism, but pushed her toward rigorous abstraction, where every line and shape was constructed with the same care and precision with which she would depict a human bone. This attention to detail and structure is reflected in her pictorial compositions, where space becomes a complex and articulated organism, similar to a skeletal system.Anatomy, then, was for Vieira da Silva a key to understanding and representing space in a new way, going beyond simple representation to formal and conceptual synthesis.

7. She worked through a slow, meticulous and daily creative process

Vieira da Silva worked with extreme patience and dedication, often taking years to complete a single painting. He loved to keep his works in the studio for long periods, observing them under different light conditions and at different times of the day to capture new nuances and possibilities. Her painting was not an impulsive act, but an ongoing, reflective process that occupied every moment of her life.

As she recounted, the best time to work was after five o’clock in the evening, when she felt freer of worries. She worked on several paintings at once, and even during daily activities such as answering the phone or receiving visitors, she loved to stay in the studio looking at her canvases, aware that every change in light changed their appearance. This daily dedication and the ability to return to a work several times to refine it are distinctive features of his creative method.

8. In her works, space and human figure merge

In Vieira da Silva’s paintings, space and the human body cease to be separate entities and merge into a single dynamic and interconnected reality. An emblematic example of this fusion is Portrait de Marie-Hélène from 1940, in which the artist portrays herself at work in her studio. In this work, the surrounding space seems almost to dance, with colors, shapes and perspectives intertwining in a continuous flow. The figures emerging from the canvas are not static entities, but rather moving elements that expand and contract, harmoniously integrating with their surroundings.

This fusion of body and space reflects Vieira da Silva’s conception of painting as a living organism, in which each element contributes dynamic balance and emotional depth. Traditional perspective is overcome to make way for a more complex and layered vision that engages the viewer in a unique visual and sensory experience. The “jewel-like squares” that fill the canvas, arranged side by side, create a feeling of movement and depth, revealing a series of dancing figures that seem to emerge from the space itself. This ability to merge space and human figure is a constant in Vieira da Silva’s work, making it recognizable and distinctive.

9. Art for her was a dialogue between the real and the imaginary, between order and chaos

Vieira da Silva’s visual vocabulary is based on a continuous tension between what is real and what is imaginary, between order and chaos. Through the use of geometric shapes, vibrant colors, and complex perspectives, his works evoke labyrinthine and ambiguous spaces in which perception multiplies and stratifies. These spaces are never uniquely defined, but open to multiple interpretations, challenging linearity and simplicity.

His painting is a constant dialogue between structure and movement, between elements that attract and repel, reflecting the complexity of reality and human experience. A work like La Chambre à carreaux from 1935, with its tiled room composed of squares and lozenges that ebb and flow in a rhythmic composition of complementary and dissonant colors, perfectly embodies this tension between order and chaos. Vieira da Silva’s ability to create ambiguous and complex spaces that elude unambiguous definition is what makes his works so fascinating and rich in meaning, inviting the viewer to immerse himself in a visual world that is both familiar and mysterious.

10. Spent a period of self-exile in Brazil

In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II and the subsequent Nazi occupation of Paris, Vieira da Silva and her husband Arpad Szenes, both considered undesirable foreigners, were forced to leave France. They found refuge in Brazil, where they lived for about eight years. This period represented a forced exile, marked by economic hardship and a sense of cultural isolation. Despite the challenges, Vieira da Silva continued to paint, finding in her work a refuge and a form of expression. Far from the artistic fervor of Paris, she developed a new perspective and greater introspection, which were reflected in her works. “As a consequence of this situation or perhaps in an attempt to deal with it,” Frigeri writes, “she channeled her pain into art. During his stay in Brazil he did not paint much, but the few works he did produce are among his most ambitious.”

Despite the distance, he maintained contact with the European art world and continued to exhibit his works. The Brazilian experience, though difficult, helped strengthen his connection with painting and solidified his unique and unmistakable style, enriching it with new nuances and sensibilities. In 1947, after the end of the war, the couple returned to Paris, where Vieira da Silva quickly resumed his artistic activity, gaining increasing recognition and establishing himself as one of the most important figures in European abstract art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.