Helen Frankenthaler (New York, 1928 - Darien, 2011) was one of the leading exponents ofAbstract Expressionism, a movement that dominated the American art scene from the 1940s to the 1960s, and which saw the emergence of such notable figures as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Her art (in Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, from Sept. 27, 2024 to Jan. 26, 2025, the largest exhibition dedicated to her that has ever been held in Italy: Helen Frankenthaler. Painting Without Rules, curated by Douglas Dreishpoon) is often associated with the subgenre of Color Field, which is distinguished by its use of large, flat, translucent surfaces of color in contrast to the more aggressive and tumultuous gestures typical of action painting.

One of Frankenthaler’s major contributions was the development of an innovative technique called soak-stain (“spot imbibition”), which allowed color to penetrate directly into the unprepared canvas, creating liquid, luminous surfaces. This technique, influenced by Pollock but at the same time marking a distance from his work, was a turning point that would shape her work.

Frankenthaler was a woman on the cutting edge, not only for her art, but also for her ability to assert herself in a male-dominated art world. Through a continuous exploration of painting, color and emotion, she took her career to new heights, becoming one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. Her fascinating personality, keen intelligence and ability to connect with the public through art make her a subject of enormous interest. Let’s look at ten key aspects of Helen Frankenthaler’s art, trying to shed light on what made her unique in contemporary art.

Helen Frankenthaler was born on December 12, 1928 in New York to a family of Jewish descent. Her father, Alfred Frankenthaler, was a New York State Supreme Court Justice, while her mother Martha Lowenstein was an emigrant from Germany. The influence of the family’s cultural and intellectual background was instrumental in Helen’s artistic growth, and from an early age she showed a strong interest in art. Frankenthaler’s education began at the Dalton School, a progressive school in New York City, where she studied under painter Rufino Tamayo. Tamayo, known for his fusion of surrealism, abstractionism and Mexican culture, introduced her to the importance of color and form. She later attended Bennington College, where she deepened her study of European and modern art, and where she came into contact with the writings of Clement Greenberg, the famous art critic who would play a crucial role in her career and personal life.

Frankenthaler’s academic training proved crucial to her career, as it provided her with a technical and theoretical background that enabled her to develop a personal and distinctive style that combined influences from the past with contemporary innovation. European art, in particular, had a profound influence on Helen Frankenthaler. During her education at Bennington College, Frankenthaler studied in depth the great European masters, including Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, and their teachings played a crucial role in the development of her visual language. Cézanne, in particular, influenced the way Frankenthaler conceived of landscape painting. Although his work is far removed from Cézanne’s figurative painting, the idea of breaking down natural forms into planes of color is evident in his canvases. Cézanne, through his innovative approach to landscape painting, thus provided Frankenthaler with a reference point for his exploration of the relationship between color and space.

“I believe in tradition,” Frankenthaler said. “In my case, my training-my roots-was based on Cézanne, Picasso’s analytic Cubism, and Braque, Kandinsky, Miró, Gorky, Pollock and many of their contemporaries, mentors and friends. I learned to appreciate the masters of the past, the 15th century, the Renaissance, along with the work of my contemporaries. Sometimes for an artist, I think aesthetic developments creep in almost without warning, with a subtle urgency, an unconsciously planned surprise. There is a natural order.”

Helen Frankenthaler’s work is related to abstract expressionism, a movement in which her inspiration germinated, although her art has evolved significantly from that of her contemporaries. From the earliest years of his career, Frankenthaler came into contact with some of the most influential figures of this movement, such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. It was in the context of abstract expressionism that he developed his interest in color and non-figurative composition.

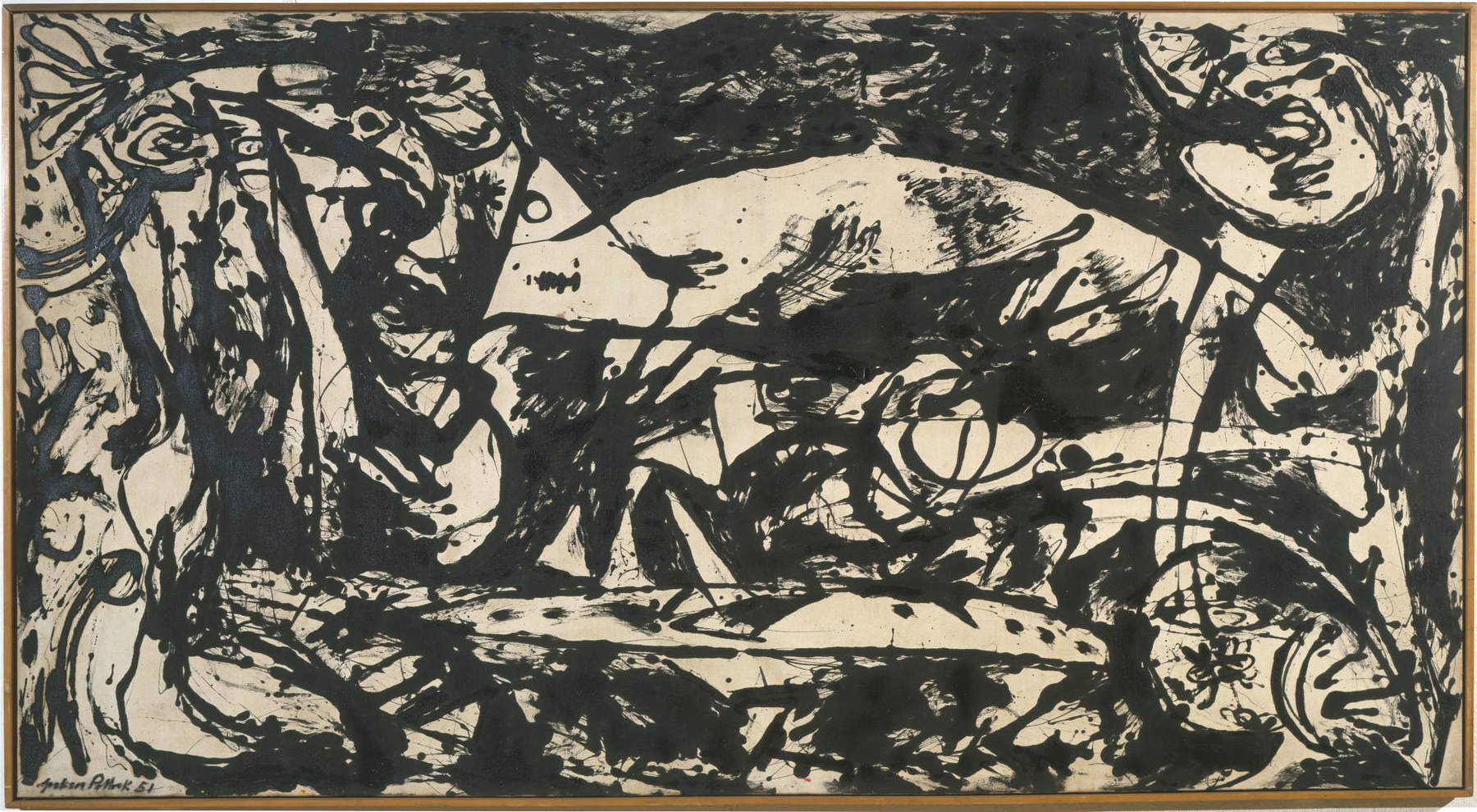

However, Frankenthaler differed from his colleagues in his approach to painting. If the abstract expressionists often used violent, marked gesture to express their emotions on canvas, Frankenthaler preferred a more lyrical and poetic approach, which manifested itself in her fluid use of color. She was influenced by Pollock’s work, but found a way to transform her dripping (dripping) technique into something more subtle and less aggressive, and above all subjected to tighter control. Helen Frankenthaler’s art is thus a balanced combination of various souls: poetry and abstraction, technique and imagination, control and improvisation. This is clearly seen in a work like Open Wall of 1953: it was, the artist said, “an experiment in creating a kind of sense of space and boundary.... Ultimately the essence of the painting, what elicits a reaction, has very little to do with the subject itself, but rather with the interaction of spaces and the juxtaposition of forms.”

His art was distinguished by his ability to create fluid and transparent surfaces, in which color seemed to float on the canvas in a delicate harmony of form and chaos. This approach, which combined spontaneous action with a refined sensibility for color and composition, placed her within the movement, but at the same time marked a certain distance from it. Frankenthaler certainly did not replicate Pollock’s explosive gesturality, but she nonetheless took important cues from the freedom and unconventional approach to painting that he introduced, deriving from Pollock the idea of painting as an intuitive process.

Regarding Pollock’s work Number 14 , one of her colleague’s works that most inspired her, Frankenthaler had this to say, “It was more than simple drawing, weaving, weaving, dripping of a stick dipped in enamel, more than simple rhythm. It seemed to have such complexity and order that, at that moment, it elicited a reaction from me. Something more... baroque, more drawn and with some elements of abstract realism or Surrealism, or a reflection of them... It is a totally abstract painting, but for me it had that extra quality.”

One of the most celebrated aspects of Frankenthaler’s work is the development of the " soak-stain“ (”spot imbibition“) technique, which marked a radical shift in the way painting was done in the 1950s. Introduced in 1952, the technique involved pouring or diluting color directly onto the unprepared canvas, allowing the pigment to penetrate and ”stain" the fabric. This method allowed her to achieve effects of transparency and fluidity that were impossible with traditional oil or acrylic painting methods.

The work that marks the debut of this technique is Mountains and Sea (1952). The canvas, large in size and light as a splash of water, revolutionized the world of abstract art. The use of thinned oil paint applied to untreated canvas allowed the color to be absorbed and diffuse, creating an ethereal, shaded effect that would become Frankenthaler’s signature.

The technique involved four steps. First, the preparation of the canvas: Frankenthaler used large canvases that were not prepared with gesso and glue (this choice allowed the colors to be absorbed directly into the fibers of the canvas). Second, color dilution: oil colors were diluted with turpentine or other solvents to achieve a fluid and transparent consistency. This process facilitated the spread of color on the canvas. Beginning in 1962, Frankenthaler also began to experiment with acrylic colors, adopting them permanently later. Third, theapplication of color: on the canvas lying horizontally, Frankenthaler would pour, spray or apply the colors, allowing them to expand and absorb into the fabric. The last step was the artist’s intervention in the painting. Helen Frankenthaler used a variety of tools to manipulate the colors, such as brushes and sponges of different shapes and sizes, rollers to apply the color evenly, rags to spread or blend the color, hands and fingers for direct control, pipettes and syringes for precise application, and sticks, spatulas, and rakes to scratch or draw on the fresh surface. Her creativity also led her to use unconventional objects, such as a spaghetti spoon, highlighting a practical and innovative approach.

A central figure in Frankenthaler’s life and career was Clement Greenberg, one of the most influential art critics of the 20th century. Greenberg was not only a mentor and supporter, but also a romantic partner of the artist for many years. Their relationship, which began in the early 1950s, had a significant impact on Frankenthaler’s career, as Greenberg was a major proponent of abstract expressionism and, later, the “Color Field.”

Greenberg saw in Frankenthaler an artist who could push forward the boundaries of lyrical abstraction and supported her in finding a personal voice within the context of abstract art. The critic was fascinated by her ability to blend a refined pictorial language with innovative technical experimentation. Frankenthaler, for his part, appreciated Greenberg’s critical intelligence, although he sought to maintain his own artistic autonomy.

Their bond was an intellectual as well as romantic collaboration, and Greenberg played an important role in promoting Frankenthaler’s work to galleries and museums. However, the artist managed to demonstrate her creative independence over the years, gradually detaching herself from Greenberg’s shadow to establish herself strongly as one of the leading exponents of American abstract painting.

In 1958, Helen Frankenthaler married Robert Motherwell (Aberdeen, 1915 - Provincetown, 1991), one of the most important painters in the United States and another leading exponent of Abstract Expressionism. His marriage to Helen was his third, and because they both came from two wealthy families they were also known as “the golden couple.” They spent their honeymoon in Europe, between Spain and France. Their marriage had a beneficial effect on their art, despite the major character differences that separated them: indeed, Helen Frankenthaler was outgoing and very sociable, while Robert Motherwell was reserved and introverted.

Two years after their marriage, in 1960, they rented a villa in Alassio, Liguria, where they produced paintings inspired by the sun and the sea, characterized by an intense joie de vivre. The seaside experience continued in their homeland: in fact, the couple used to spend their summers in the seaside resort of Provincetown, Massachusetts, where they established their studios. We are also left with works celebrating this love: Helen Frankenthaler, for example, designed a Valentine’s Day card for her husband, and he himself dedicated works to his beloved, such as Helen’s Collage, made in 1957, shortly after they met. The marriage lasted until 1971, when the two artists divorced.

The work Mountains and Sea (1952) is considered one of Helen Frankenthaler’s most significant masterpieces, if not her most important work, and one of the turning points in postwar American abstract art. Made when the artist was only 23 years old, this painting marked the beginning of a new chapter in abstraction, profoundly influencing a generation of “Color Field” painters such as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, who saw the work just six months after it was painted.

The work was inspired by a trip Frankenthaler took to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and the title itself evokes nature’s vastness and sense of open space. However, Mountains and Sea is not a figurative representation of the landscape, but an emotional and abstract translation of the feelings the artist experienced when confronted with that landscape. The innovation of Mountains and Sea lay in the method used to paint it: the soak-stain technique.

The painting defies the boundaries between the figurative and the abstract. Its goal was to evoke feelings and atmospheres, offering the viewer a visual experience that was free from specific interpretations. Mountains and Sea became one of the most cited works in the context of postwar American painting and influenced a number of emerging artists, so much so that it was even called “the Rosetta Stone of the Color Field.”

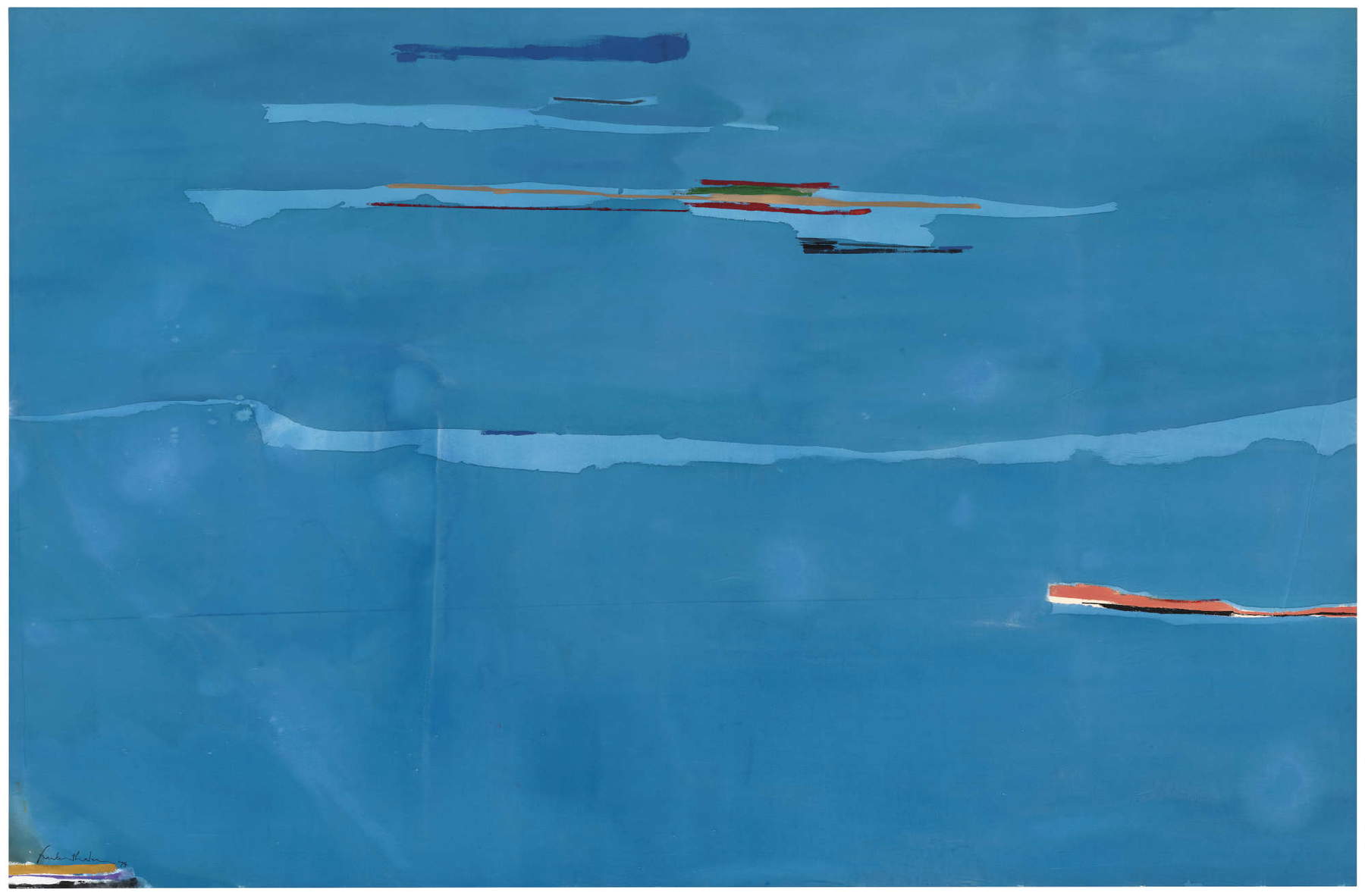

One of the central aspects of Helen Frankenthaler’s career is her contribution to the development of the Color Field, a movement that emerged in the 1950s as a reaction to the more dramatic tendencies of abstract expressionism. The Color Field artists (the term was coined by Clement Greenberg in 1955), whose major exponent was Mark Rothko, distanced themselves from the gestural intensity and expressive brushstrokes typical of artists such as Pollock and de Kooning, focusing instead on theuse of large areas of flat, uniform color.

Frankenthaler was a pioneer of this approach. His innovative use of the “soak-stain” technique allowed the colors to appear light and translucent, creating luminous backgrounds that seemed to flow freely across the canvas. This formal simplicity became a trademark of the “Color Field,” influencing artists such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski. In particular, Morris Louis, after visiting Frankenthaler’s studio in 1953, adopted his technique and took it to new levels of abstraction.

The importance of Frankenthaler’s contribution to the “Color Field” cannot be underestimated. His exploration of color as an autonomous means of expression was among the most original of his time.

One of the hallmarks of Frankenthaler’s work is the way she used color not only as a visual element, but as an emotional language. From his earliest works, color was central to his artistic pursuit, and the way he applied it to his canvases redefined the role of color in abstract art.

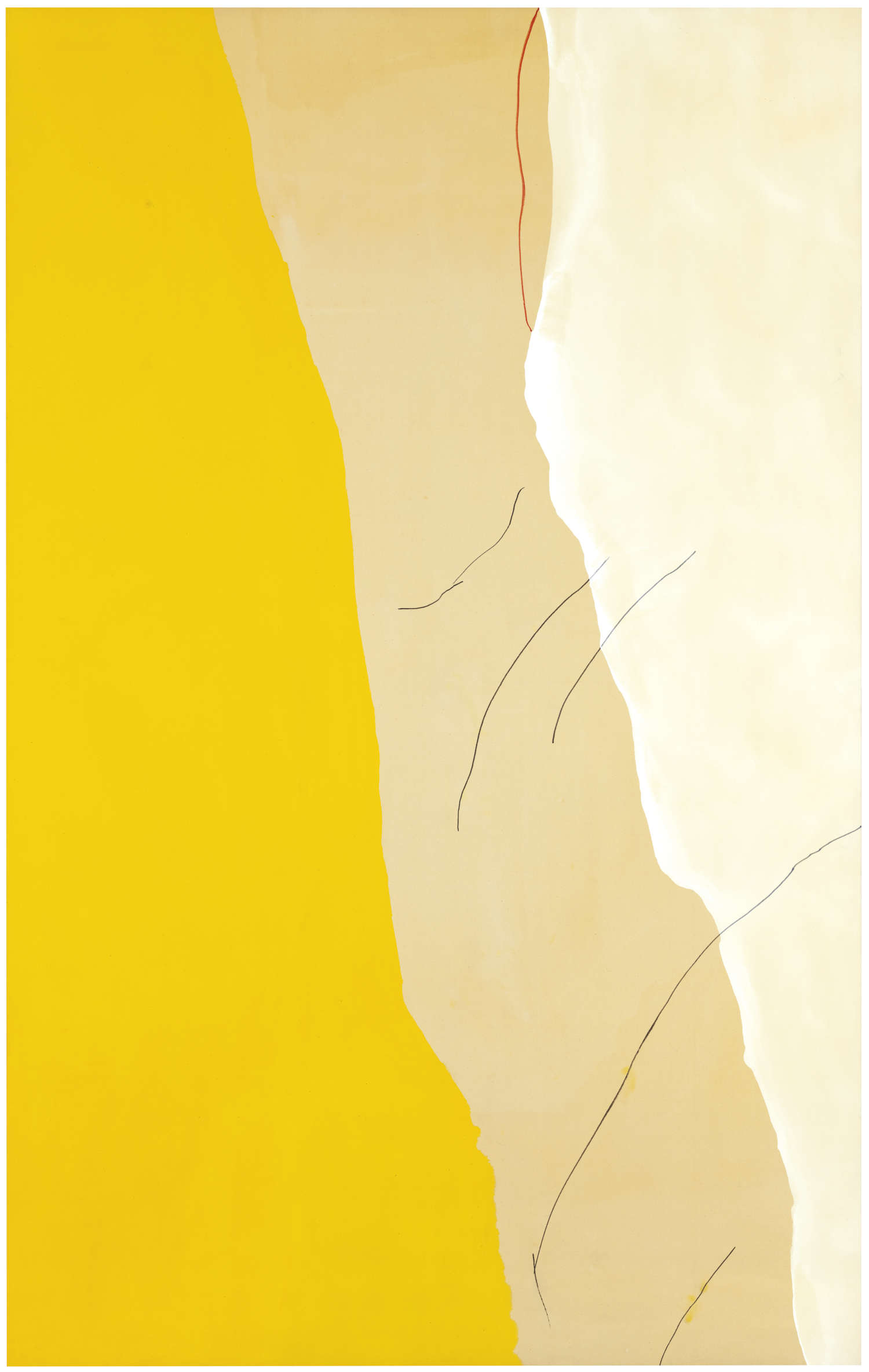

Frankenthaler used color expressively, seeking to evoke moods and feelings rather than describing shapes or figures In works such as Alassio (1960), painted during a period of work in Liguria, the colors seem to gush from the canvas, creating a sense of fluidity that conveys immediate, palpable emotion. The yellows, deep blues, and translucent reds are not just chromatic tones, but vehicles of expression. This sensitivity to color was not only visual, but also tactile: his paintings often suggest a sense of lightness and movement, as if the colors had been blown onto the canvas or naturally expanded into infinite space. In this sense, Frankenthaler was among the Color Field artists who were able to transform color into a visual experience.

In the 1970s, this attitude of hers underwent further development: at that time, in fact, she experimented with intense, atmospheric panoramas , sometimes verging on monochrome. An example of this phase is the painting Ocean Drive West #1, of which she said, “On Ocean Drive West you always find yourself staring at the horizon line.... There are blurred areas of Long Island beyond the Sound, some are visible, some are not. I was not looking at nature or a seascape, but at the pattern present in nature, just as the sun or the moon can be seen as circles or as light and shadow.”

In addition to painting, Helen Frankenthaler was also a leading figure in the field of graphic design and printmaking, where she brought the same innovative sensibility that had characterized her painting work. Beginning in the 1960s, Frankenthaler began to explore printmaking techniques such as especially woodcut, working with some of the most prominent U.S. printing workshops, including Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) and Tyler Graphics.

His approach to printmaking, initiated in the 1970s (his first woodcut, East and Beyond, was executed at ULAE in 1973), was in line with his painting: he experimented with transparency and color layering, using printmaking to explore new visual effects that he could not achieve with traditional painting. In particular, he specialized in the use of color woodcuts. His woodcuts of the 1980s and 1990s, such as Tales of Genji III (1998), are considered among the most innovative works in contemporary graphic art.

Helen Frankenthaler always experimented by alternating painting on canvas with painting on paper, the latter being considered a more manageable and easily replaceable medium when needed. She worked on paper especially after her marriage to Stephen DuBrul in 1994; her works on paper seem to mark a turning point. These works express a renewed vitality, an openness to the future that, however, does not forget the past. His art, even in these moments of renewed optimism, retained a sense of reflection on previous experiences. This sentiment is evident in works such as Solar Imp and Cassis, which celebrate his new phase of life. In these paintings, Frankenthaler uses broad sponges to imprint rectangles of color on paper, creating compositions characterized by clear, clean calligraphy. In Solar Imp, the rectangles are arranged under two black shapes, reminiscent of the figures that dominated her earlier works, made during her marriage to Robert Motherwell. These elements not only testify to a connection with the past, but also suggest a stylistic and personal evolution.

Frankenthaler always had a profound vision of beauty, a concept he continued to explore and defend even when many of his contemporaries, particularly younger and politically engaged ones, tended to consider it obsolete or worthless in the context of modern art. For Frankenthaler, beauty was anything but superficial or trivial; it was, on the contrary, a representation of the human condition in its entirety. His works, even those on paper, reflected the transience of existence and the inevitable passage of time, as can be seen in works made in the last years of his career, including Southern Exposure, one of his most intense paintings on paper. These works communicate a deep awareness of the passing of time, making the transience of life palpable.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.