Temples of Darkness: on the Neoclassicism of �tienne-Louis Boullée

On the eve of the French Revolution, before the fall of the heads of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, a desire for new moral values in society and in the various arts was felt throughout France. With the end of the Baroque style, for the artist the new canon of taste is reason. For this reason, the great civilizations of the ancient world, especially the Greek and Roman, are taken up as ideal models in life, literature and art. In the pictorial disciplines, the French revolutionaries and artists of the revolution see themselves as Greek redivatives, as their works aim to convey the taste of ancient greatness. From the spirits of the Revolution, the Enlightenment period, and the Greek revival in the revival of classical works, an entirely new style developed in art and architecture: Neoclassicism, which took on character in the second half of the eighteenth century and the first decade of the following century. The Neoclassicism current also marks the beginning of the opening of new exhibition spaces within which ancient sculptures are placed: indeed, the purpose of exhibitions becomes to evoke the same spaces that the works originally occupied. While Renaissance classicist culture proposed the works of Greek and Latin writers as canons to be followed in order to be able to determine an objective canon of beauty, neoclassical culture is characterized by the recovery of classical forms from which to draw in the search for perfection, with a new sensitivity toward the arts.

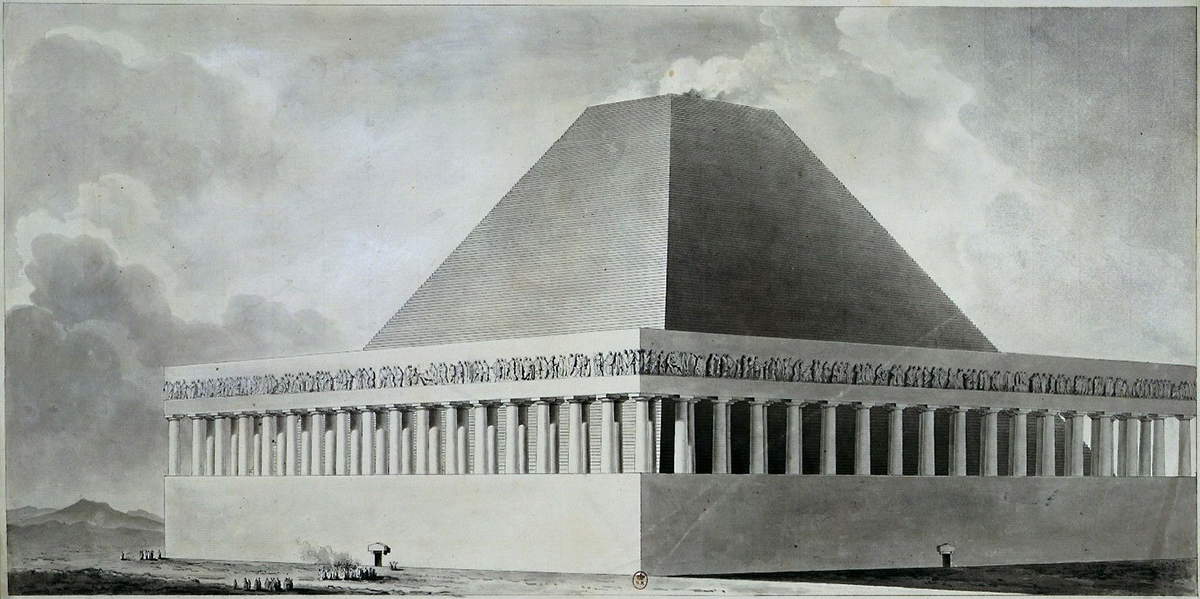

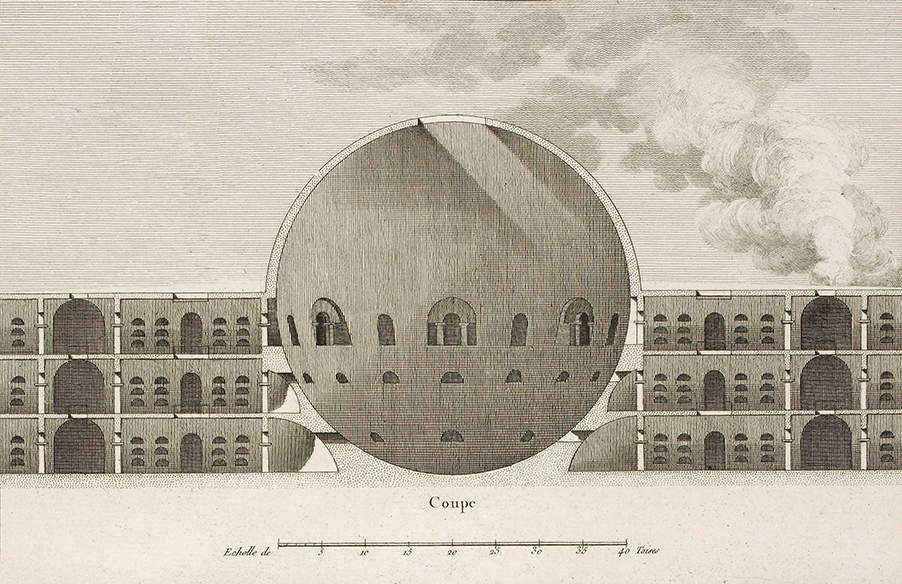

During the first half of the eighteenth century, the proposals submitted for the attention of the competitions promoted by theAccademia di San Luca in Rome manifested an aspiration to achieve designs of grandiose dimensions and a predilection for elementary geometric forms. The new ideas represent a crucial element in the architectural production of the period, contributing significantly to outlining the new directions of architecture internationally. No later than 1750, titanic elevations also became a recurring element in French neoclassical production. In this context, among the most influential architects of the period, the name of Étienne-Louis Boullée (Paris, 1728 - 1799) stands out. Marked by the evolution of the artist’s scientific and philosophical ideas, Neoclassicism led Boullée to the realization of visionary projects based on the ideal society-city and the conception of architectural utopia. The artist-architect succeeds in bringing to life neoclassical structures that carry with them precise aesthetic canons: classical architectural order, symmetry of geometric forms, and majestic illustrated spaces. While grand and imposing in character, his creations possess such high dimensions that even today they unfortunately remain unrealizable projects. It was from the union of these elements that Boullée, followed by the architect Claude-NicolasLedoux (Dormans, 1736 - Paris, 1806), succeeded in bringing to life a style never seen before:Buried Architecture. A titanic and evocative architecture that bases its construction on the memory of classical and Egyptian funerary monuments as seen in the Egyptian Genus Cenotaph: Perspective Elevation of 1786, or even inspired by early Christian catacombs, such as that in Ledoux’s Section of a Cemetery Plan for the City of Chaux of 1785, enhancing their grandeur only to be reinterpreted in a new monumental architecture.

Not to be outdone, in 1785 Pierre François Léonard Fontaine presented his illustration with pharaonic features entitled A sepulchral monument for the rulers of a great Empire, also a visionary and utopian project based on Egyptian funerary architecture.

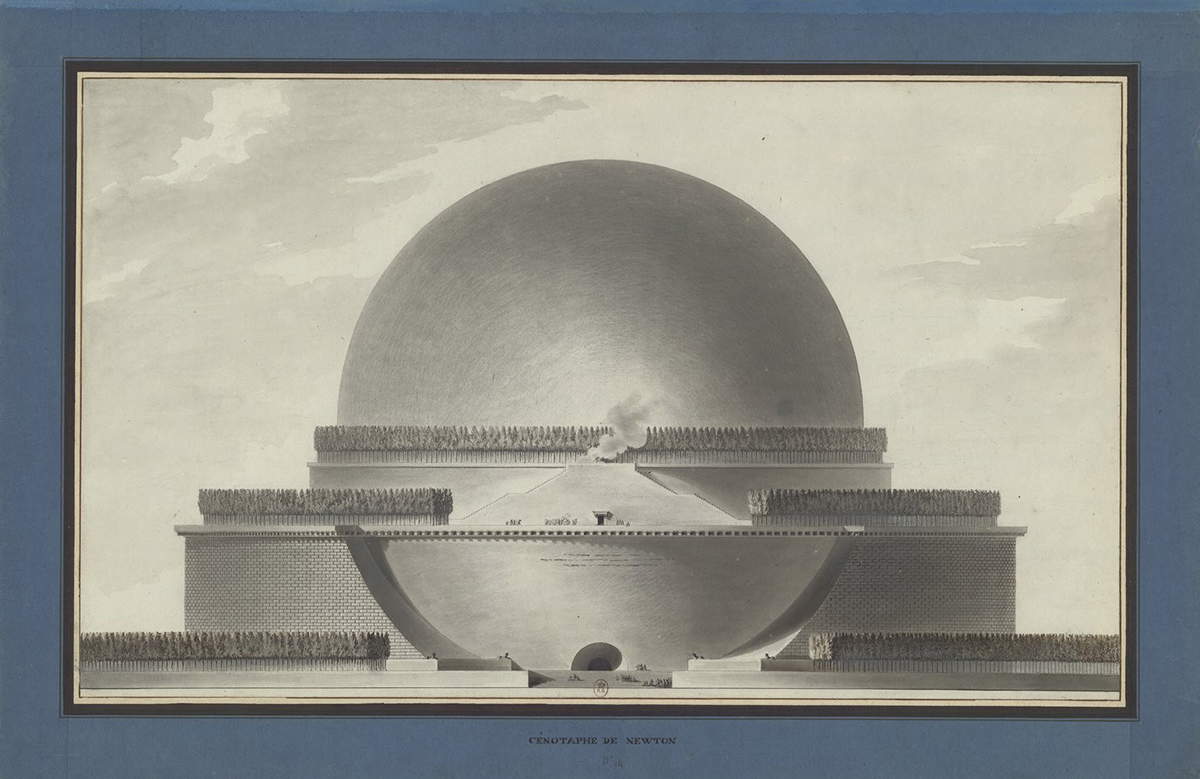

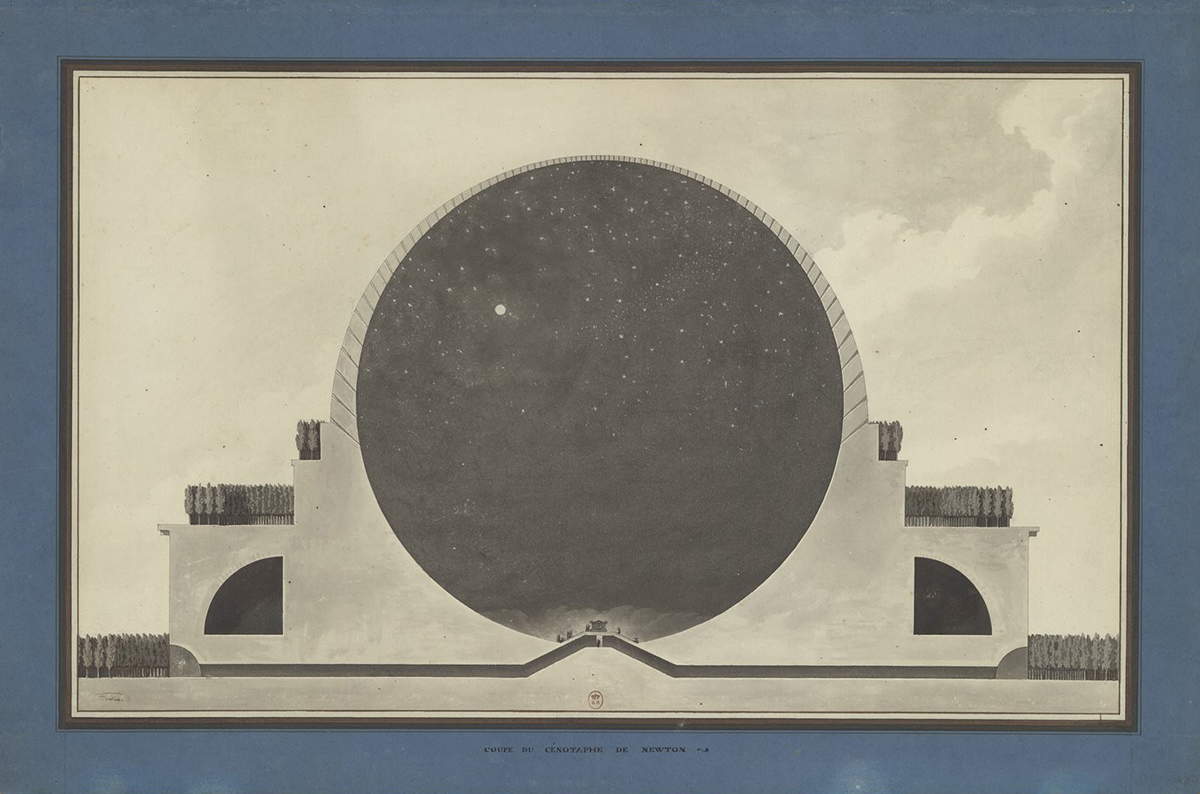

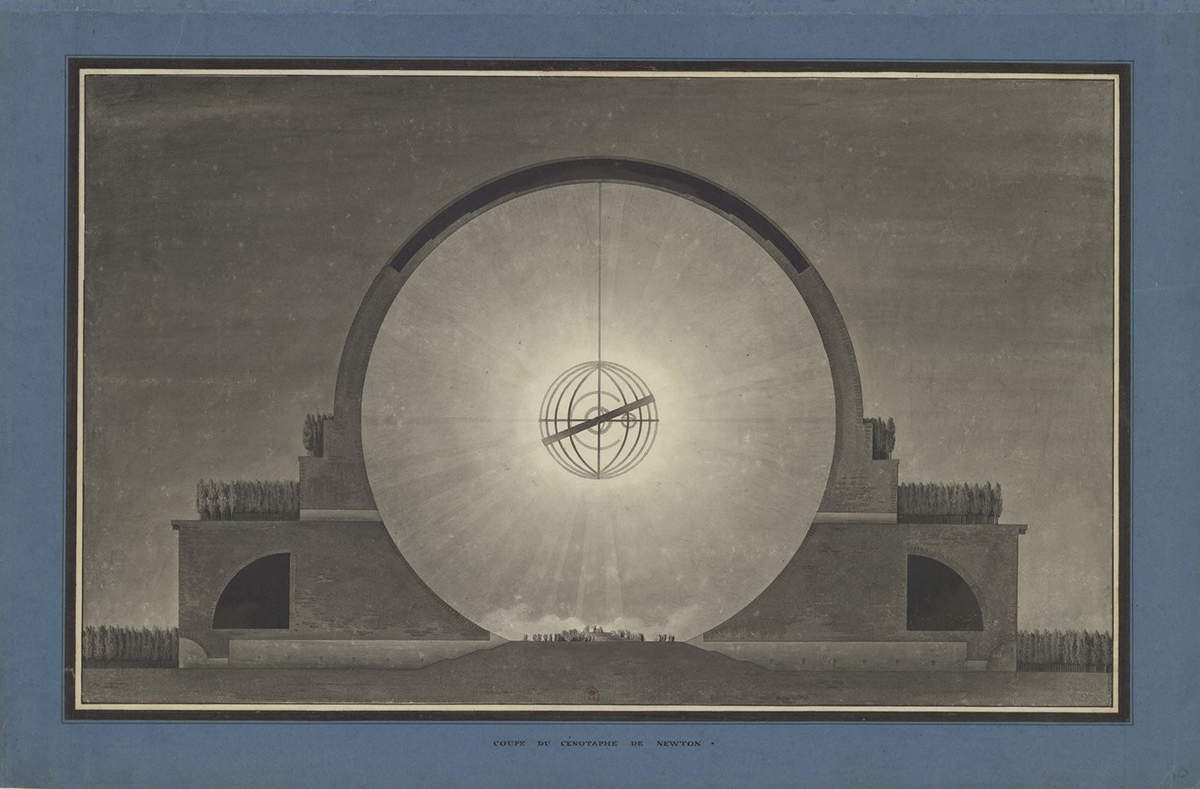

Indeed, the interest of Boullée and the other architects lies in being able to strip their buildings of all eighteenth-century ornamentation, asserting that the only decorative function allowed should be the shadow and light generated by the geometric forms that envelop the structures. In order for the works of revolutionary architecture to convey the evocative impact and a deep reverence for the grandeur and majesty of the structures of ancient civilizations, Boulléand analyzes in depth the dark spaces of pyramids, necropolis, and tombs that in the past were accessible only by torchlight, as they were both burial sites or sacred places and thus were deliberately shrouded in darkness, as well as gathering places for religious services and places of prayer. The purpose of these spaces was to remain away from sunlight so that no one could find them, like the early Christian catacombs. From the research on light, Architecture of Shadows was also born: founded on the play of light/shadow, making the illustrated structures achieve an even darker character, far from our time and enigmatic. Interior view of the Metropolis at the time of Corpus Christi in 1781 (inspired by Hubert Robert’s 1773 painting The Finding of the Laocoon ) and Newton ’s famous Cenotaph, surely the most famous illustration of Boullée’s entire career, are clear examples.

Especially, the design of Newton’s Cenotaph, would aim to evoke both grand and eerie feelings in the observer faced with a space designed to replicate the immensity of the universe. The cyclopean cavity within the cenotaph, according to Boullée’s study, should contain the memorial sarcophagus with Isaac Newton’s remains, and could offer different cosmic visions during the day and night. This would make it possible to recreate a miniature model of the universe, the dynamics of which were discovered by Newton through his law of universal gravitation.

For the realization of light in his designs, the architect turned to memories of the effects that natural light produces in open spaces, anticipating in a sense the Impressionist current, which focused on the study of light and its reflections in paintings made en plein air. Almost as a precursor to Monet, Boullée analyzes the mysterious effect of mist in the forests he used to frequent during his youth, and the moonlight of the starry sky. Indeed, he asserts that the effects of mysterious light produce a majestic, moving whole of magnificent magic. In order also to succeed in achieving the character of such a composition, he decides to take winter as a reference point, since unlike summer and spring it represents the darkest season, a season that freezes the world. The forests remain bare, occupied only by the skeletons of now-dried trees. On paper, the representation of the effects of light turn out to be dull and cold, restoring to the architecture the shadowy and decisive features that manage to enhance the essential geometric forms without ornamentation. Boullée’s revolutionary and visionary architecture thus offers a distortion of the heritage of classical antiquity, which simultaneously acquires a profound ethical and evocative significance, enriched by fervid symbolic and visionary impulses.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.