Suspended between sea and sky: the scales of Bocca d'Arno in art

Between October and November 2023, the whole of Europe is lashed violently by storm Ciarán, which also hits Italy. Tuscany is one of the hardest hit regions both inland and along the coast; the damage count is very heavy, eight dead and several million euros in damages. In the face of this disastrous bulletin, which has broken numerous lives, a piece of news has passed under the radar that in another situation would certainly have aroused interest. Among the victims of this catastrophe were some of the retoni, iconic structures deputed to fishing that characterize the skyline of some stretches of the Arno River and in particular its mouth known as Bocca d’Arno.

The brutal sea storms caused by the storm damaged several of them, a video released on the internet shows how among the waves one was swallowed up, perhaps among the most representative because it is located right at the mouth between the sea and the river, in the mouth at Marina di Pisa. And it was precisely in the spring of 2024 that the concessionaires of the retons returned to the issue, alerting the Region, the Superintendence and the Municipality, presenting an alarming estimate of the condition on the six structures, two of which are completely destroyed, while three others have suffered serious damage in recent years. In both cases, it is not possible to intervene unless the rock foundation is restored beforehand.

These structures are simple, mostly wooden huts built on stilts on which are hoisted fixed fishing nets, which used to be lowered into the water by hand crank. The retoni, as they are called in Tuscany, also take on the name of bilance or trabucchi in other parts of Italy, and today they have mainly a tourist function, and are included within guided tours and experiences aimed at patrons. These constructions with an ancient tradition played a role of primary importance in the economy of the area until the middle of the early twentieth century, and then lost it, however, taking on connotations of strong identity and landscape value, in scenic complexes that unravel between the sea and the Apuan mountains that serve as a backdrop. The retoni are thus a defining element of the Bocca d’Arno landscape, so much so that they have also received great attention from representations involving the river resort, from literary to pictorial to photography and cinema.

The vate of Italians, Gabriele D’Annunzio, who had a close connection with Marina di Pisa, gave his own reading of them in various passages of his writings. For him, of Abruzzese birth, they must have been a familiar memory, since the scales are in fact also widespread on the coasts of Abruzzo, and in the Triumph of Death he leaves his own particular vision of them: “The machine seemed to live of a life of its own, it had an air and effigy of an animated body.” But he also dedicated splendid words to the Tuscan retons, remembered as “great chalices” or “corollas,” “They are the hanging nets. Some hang like scales from the antennas to which they support the high and outstretched decks where man watches to turn the rope; others hang on the bows of the palischerms spending the perennial mirror that refracts them.”

No less fortunate, as we have already anticipated, they also had in the visual arts where they are immortalized in paintings and pieces of rare suggestion. After all, this part of Italy has for its charm attracted numerous artists, although their action, lacking cohesion, has never made one speak of “a school of Boccadarno,” as art historian Luciano Scardino already noted. The panic contact with nature experienced here attracted legions of painters, and among them Nino Costa (Giovanni Costa; Rome, 1826 - Marina di Pisa, 1903) certainly deserves mention, who lived and worked here for a long time. The master who initiated even a giant like Giovanni Fattori into naturalistic painting also had the merit of introducing this locality to that cohort of artists, many of whom were English, known as the Etruscan School. These painters then brought back to England views of Bocca d’Arno, helping to create a myth around the place. Among these views certainly could not miss the depiction of the well-known scales, which appear, for example, in the paintings Matthew Ridley Corbet (London, 1850 - 1902), Near Bocca d’Arno and Etruscan Scene, painted in 1885 and 1890 respectively, now in private English collections. These are works, developed along oblong formats, which resonate with the dictates promoted by Costa and his school when he solemnly pronounced, “Truth says nothing unless it is seen and reinterpreted through the feeling of thought.”

In the Etruscan School, the Roman artist also tried to precept Tuscan artists, such as the Cascina painter Francesco Gioli (San Frediano a Settimo, 1846 - Florence, 1922), to whom he wrote, “Art is love, study and freedom, nor should it be reduced to a vulgar boxing,” an attitude he found in the English school, “the most worthy and original of all the others.” Gioli seems at first to be affected by these suggestions, as evidenced also by the famous painting Bilance a Bocca d’Arno, dated 1889 and belonging to the collection of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze. The painting evokes a melancholy atmosphere, tinged with lyrical accents, where the force of nature giantizes in front of the tiny human figures of fishermen, lingering near the nets, on a frosty day that is reflected in the icy lights as much as in the heavy clothes.

His younger brother, Luigi Gioli (San Frediano a Settimo, 1855 - Florence, 1947), also took up the same subject in other canvases but developed it in a very different way and did not repeat the same quality. It shares the same title as Francesco Gioli’s work but is of a completely different intonation than the canvas by Niccolò Cannicci (Florence, 1846 - 1906) painted in 1895. Here, the naturalistic theme is dealt with in a synthetic vision of great modernity, purging the painting of all anecdotal description and instead giving it a quiet reading tinged with great poetry.

But Bocca d’Arno also becomes the territory of pictorial incursions for many of the artists who made the glories of theLabronica school , and among them perhaps the painter Ulvi Liegi, pseudonym and anagram of Luigi Levi (Livorno, 1858 - 1939), is the one who confronts the theme several times, leaving numerous paintings of great intensity. In older works such as Old Fishing Scales at Bocca d’Arno painted in 1894 and preserved in the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome or The Arno Brings Silence to Its Mouth, painted between 1880 and 1901, and now in the collections of the Livorno Foundation, the views are more terse and terrifically colored. In the latter, whose title echoes some of D’Annunzio’s words, the Arno River and its balance are captured on a late afternoon, when the sunlight is now dim and remains behind the clouds, while a feeling of stillness and silence pervades over the whole scene, increasing the feeling of melancholy.

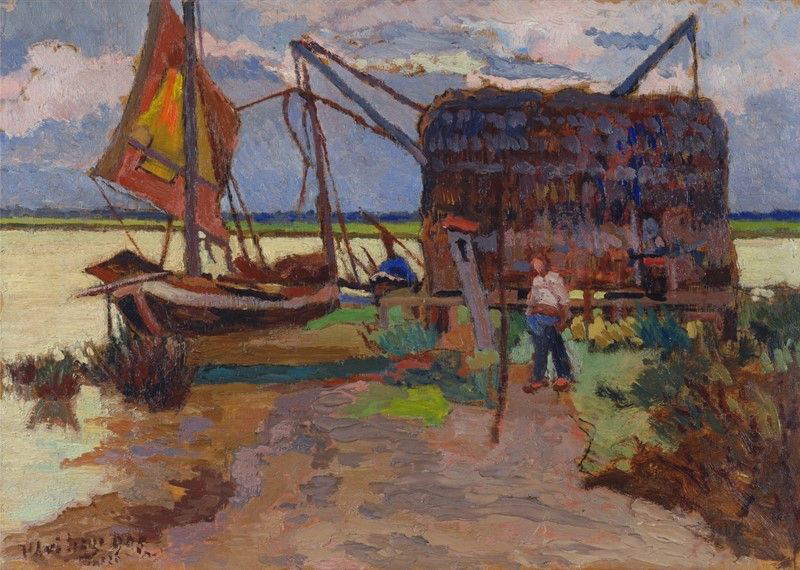

In the works after 1905, on the other hand, his palette deflagrates in a thousand fauve colors, the looser and more whimsical brushstrokes giving life to images of vibrant freshness and carefree cheerfulness. Among them, the panel with Capanne e bilance a Bocca d’Arno seems to take up the same foreshortening already tackled by Francesco Gioli, with the retoni seen in rhythmic sequence, but giving the painting a completely different temperament.

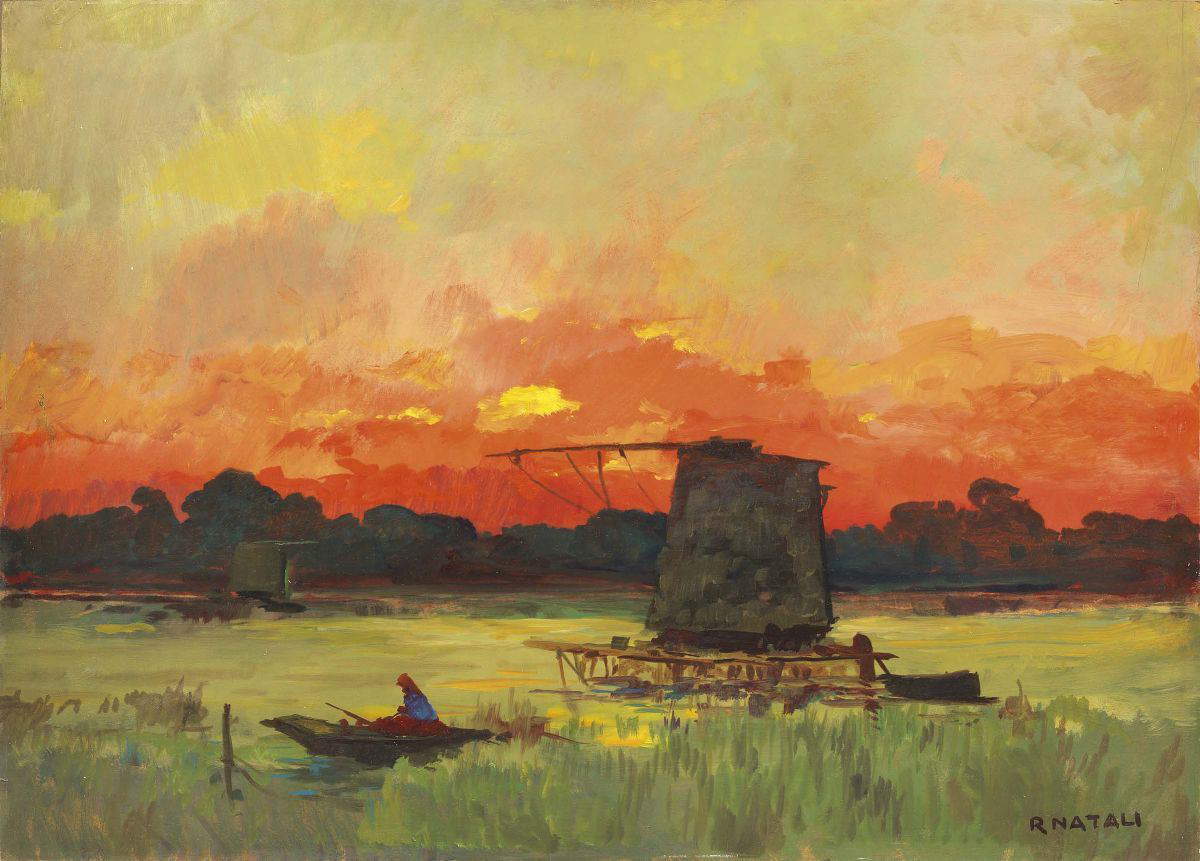

Renato Natali (Livorno, 1883 - 1979) also repeatedly paints the scales of Bocca d’Arno at various times of the day, early in the morning and when a sunset of the most intense orange explodes in the sky, until nightfall. These are works of often fluctuating quality, where the Leghorn artist meditates on the same iconography, with a hut, a small boat and a fisherman nearby, while a mantle of daffodils evoked with rapid brushstrokes unfolds around and on the shore. The work seems to respond to Natali’s aptitude for mentally and certainly not open-air reworking of the same view, ending up in the course of time to move further and further away from the real one, as happens with the scales hut, which from formerly placed on the embankment and reachable by pontoon, becomes an autonomous pile-dwelling in the middle of the water.

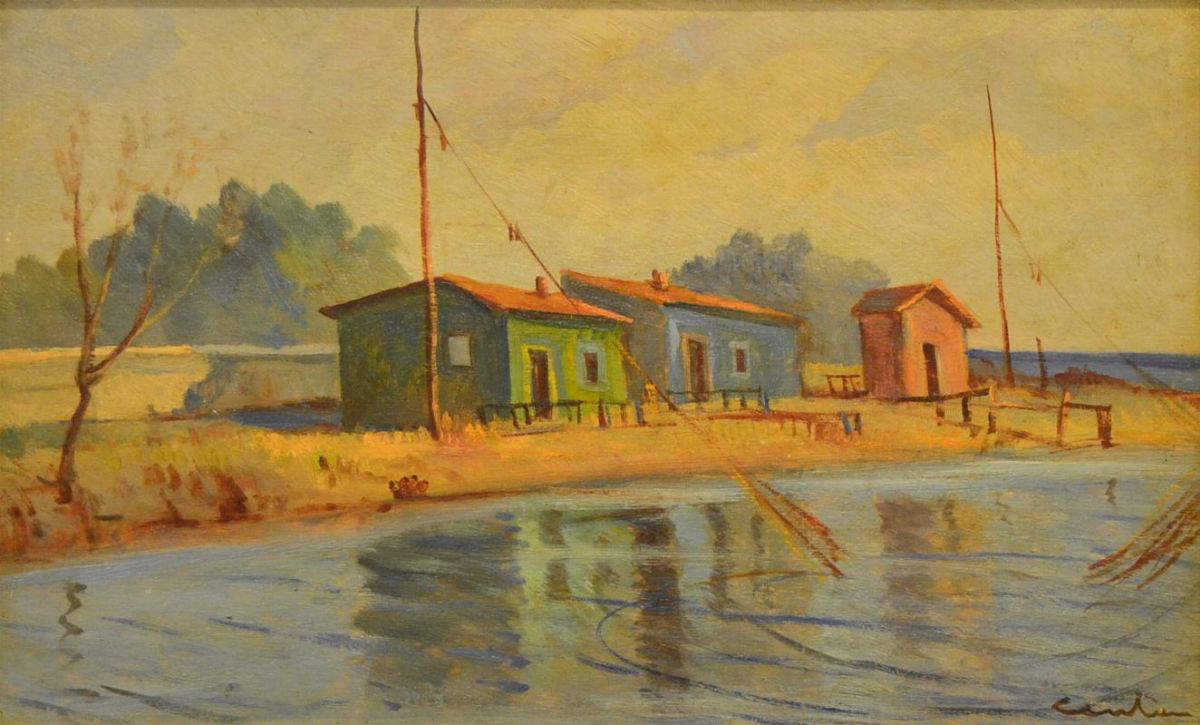

Among the Labronian artists, Vittorio Nomellini (Genoa, 1901 - Florence, 1965) and Gino Centoni (Livorno, 1891 - 1960) also confronted the theme with a coloristic, leisurely and bathing approach, so far instead from the early Romantic paintings of the Etruscan School, to which instead are closer close to the views left to us by Guglielmo Amedeo Lori (Pisa, 1869 - Viaregigo, 1913), a pointillist with a crepuscular tone, who also presented himself at the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris with two pastels entitled Bouche d’Arne and at the Venice Biennale the following year with the work Alba alla bocca dell’Arno.

Inscribed instead in a late naturalism is the small panel painted by Eduardo Gordigiani (Florence, 1866 - Marradi, 1961) entitled La foce dell’Arno, made around 1911, where in the foreground the artist places a texture of green, brown and brown backgrounds that materialize the line of the shore, on the opposite side, instead, the retons rise.

Galileo Chini (Florence, 1873 - 1956), too, did not shy away from the illusion of views of Bocca d’Arno, and when, after many years devoted to large decorations, he decided to return to easel painting between the 1930s and 1940s, his attention often turned to landscapes, and not infrequently to seascapes or river areas. Among these also appears the Pisan locality, in the canvas A Bocca d’Arno (Marina di Pisa), where his palette is bright and played on the tones of blues, purples and pinks on a simplified pictorial rendering, far removed from his decorative cycles, although there is a reference in the water line at the bottom, with its electric and descriptive stroke.

But the subject of scales also found inspiration in the completely different artists stirring in the first decades of the 20th century, such as Spartaco Carlini (Pisa, 1884 - 1949), a Pisan close to Lorenzo Viani and the group of painters of the Boheme Club of Torre del Lago. Deform to harmonize, decompose to reconstruct, this was the lesson of the master from Viareggio that Carlini made his own. In Retone on the Arno. Fluvial Landscape, a painting on cardboard now in the Museo di Palazzo Reale in Pisa, the artist reflects on Factorian poetics of landscape, but read through Viviani’s archaizing expressionism. The view of the Arno becomes almost a memory of the place, painful and somber.

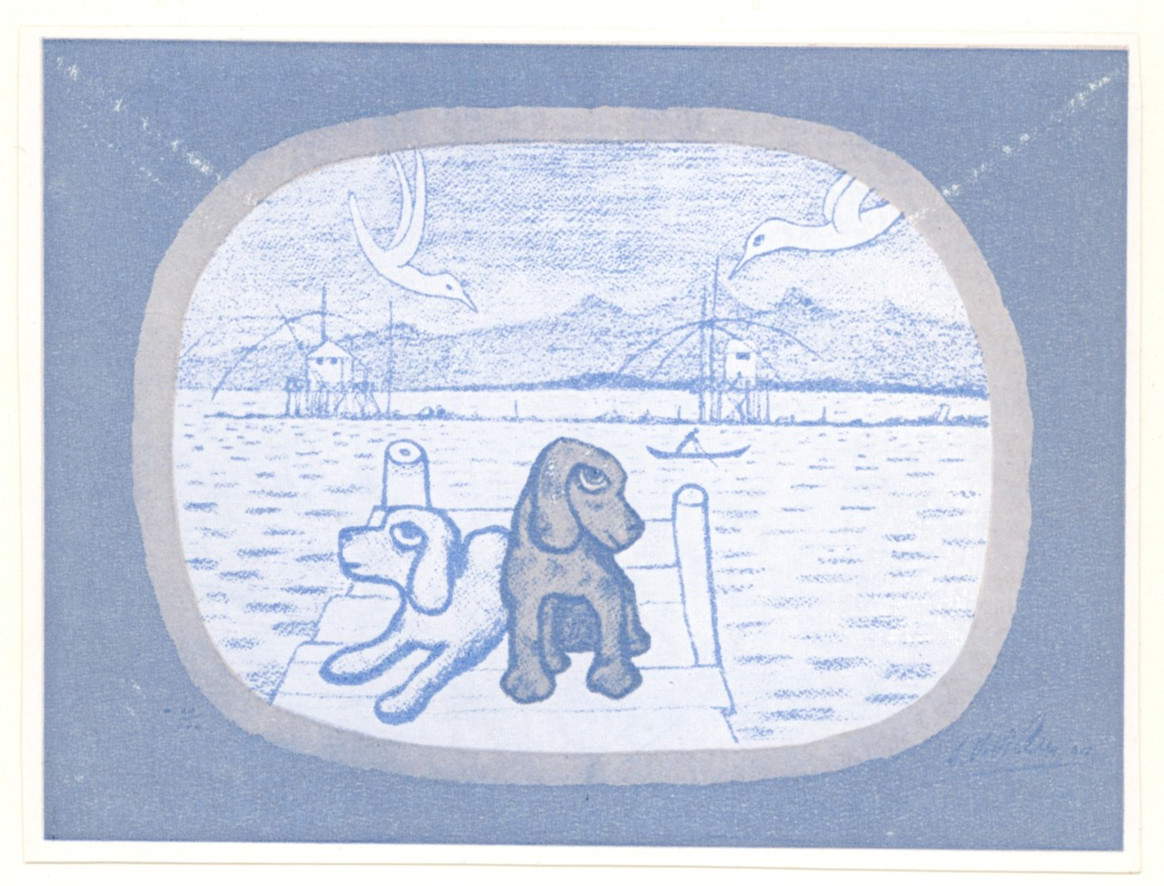

Close to a more Nordic expressionism à la Ensor is another great Pisan artist, Giuseppe Viviani (San Giuliano Terme, 1898 - Pisa, 1965), who spent long stretches of his life in Marina di Pisa, so much so that he renamed himself, with some hilarity, “Prince of Boccadarno,” because of his disinclination to travel. Of the river resort he knew how to completely renew the iconography by staging a derelict humanity against the backdrop of sea cabins or the retoni, both in his paintings and in his successful graphic work. Thus in the Bocca d’Arno lithograph, two of his passions come together, that for his beloved place and that for dogs, particularly the hunting dogs with which he surrounded himself.

Of course, this overview certainly does not pretend to exhaust an affair that instead has far more complex and vast contours, because the retons that have become a founding part of the iconography of Marina di Pisa have continued and continue to this day to be the privileged theme of an infinity of paintings, evidence of a past that is still alive in the identity of the landscape.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.