“In those years then it became very clear that continuing to design furniture, objects and similar homely decorations was not the solution to the problems of living or even to those of life, and much less did it serve to save one’s soul...” (Adolfo Natalini in Domus 517, December 1972).

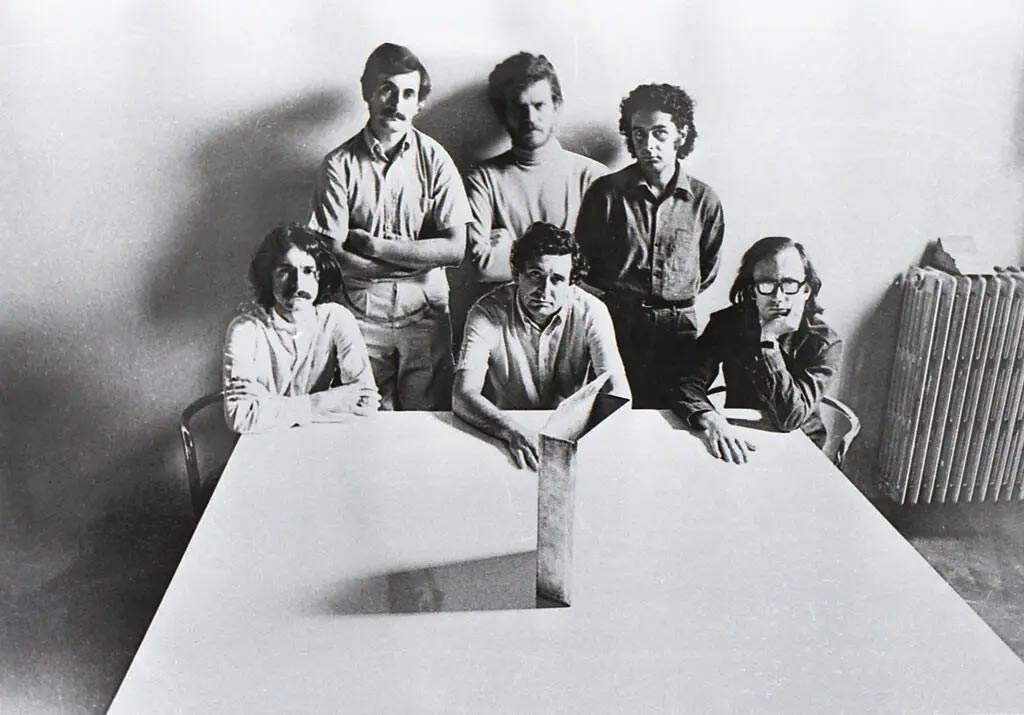

The statement by Adolfo Natalini, a founding member of Superstudio, seems almost paradoxical when read in relation to a series of design objects that takes its starting point precisely from his and his colleagues’ poetics, and which lives on to this day, namely Quaderna, produced by Zanotta. To understand how the birth of this series relates to this assumption, we need to go back in time and immerse ourselves in a very specific world, the one that was born and developing within the Faculty of Architecture in Florence around the mid-1960s: the world of Superstudio. The group was born in 1966 (the year of its first exhibition, Superarchitettura, at the Jolly gallery in Pistoia) thanks to the intuition of two young architecture students, Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, who were soon joined by Roberto and Alessandro Magris, Gian Piero Frassinelli and Alessandro Poli.

Superstudio’s poetics developed in years characterized by great uncertainty regarding the ability of the architectural culture of the time to rebuild and redesign cities, in the postwar context. In a city now shaped by functionalism, made up of shopping malls, stations, and office areas, the fundamental component of relationship, the true engine and identity of the city itself, begins to be missing.

In a historical period in which the principles of rationalism are no longer sufficient to solve the problems of living, different paths are beginning to emerge. Indeed, if architects such as Aldo Rossi looked to the past, searching the history and morphology of the city for forms and cores that could restore the sense ofliving, international radical architects (Archigram in England, Hans Hollein in Austria) project far into the future, believing that the solution lies in a great increase in the technology of design, which makes it possible to create cities governed by prefabricated components, which can be assembled together, tensile structures that can be assembled and reassembled in different places, a dynamic city in perpetual transformation. Then there is a third way, which is to be overwhelmed by the end of rationalism and, in the breaking of these rules, to find spaces to experiment with new forms and new thoughts, to redesign architecture and design. In this third way, young Italian architects begin to act, challenging the crisis of modernity. The paradigm is thus overturned: the form of objects is no longer determined by function, but by man’s way of being in space and enjoying it. From the study of human behavior, new ways of designing are thus triggered. This means that if objects change everything can change, including architecture.

Superstudio shows that it operates in this sense by drawing on the imaginaries of its time: the pop painting of Adolfo Natalini, the photography of Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, the interests in anthropology of Gian Piero Frassinelli. Rejecting a generic interdisciplinary approach, the group proposes a broadening of the field and a radical rethinking of architecture and design, going so far as to replace traditional domestic imagery with a universe of alienating objects and dystopian visions. Architecture can thus be rethought, on the one hand, as something simple and modular, but also as a macro system that connects the world.

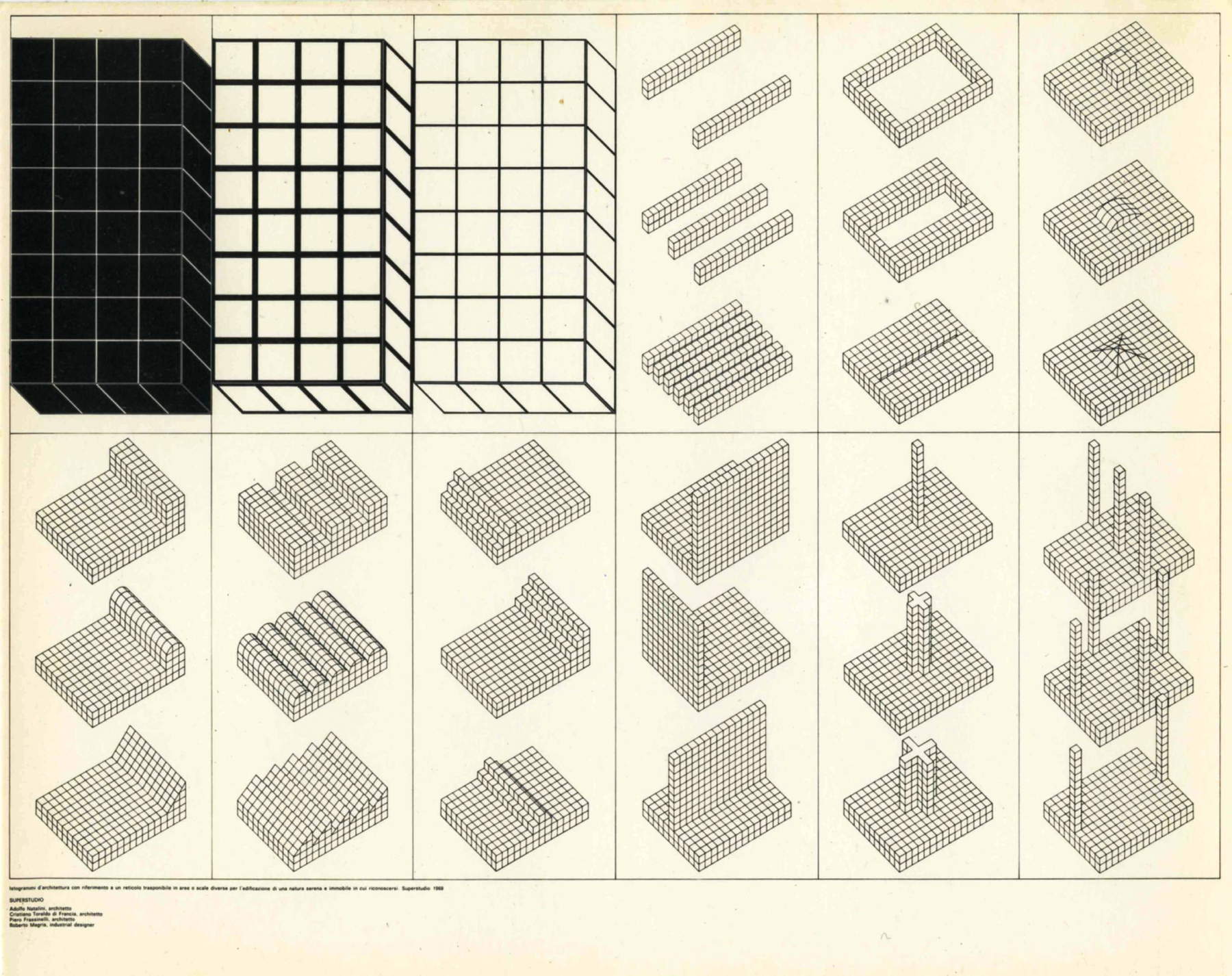

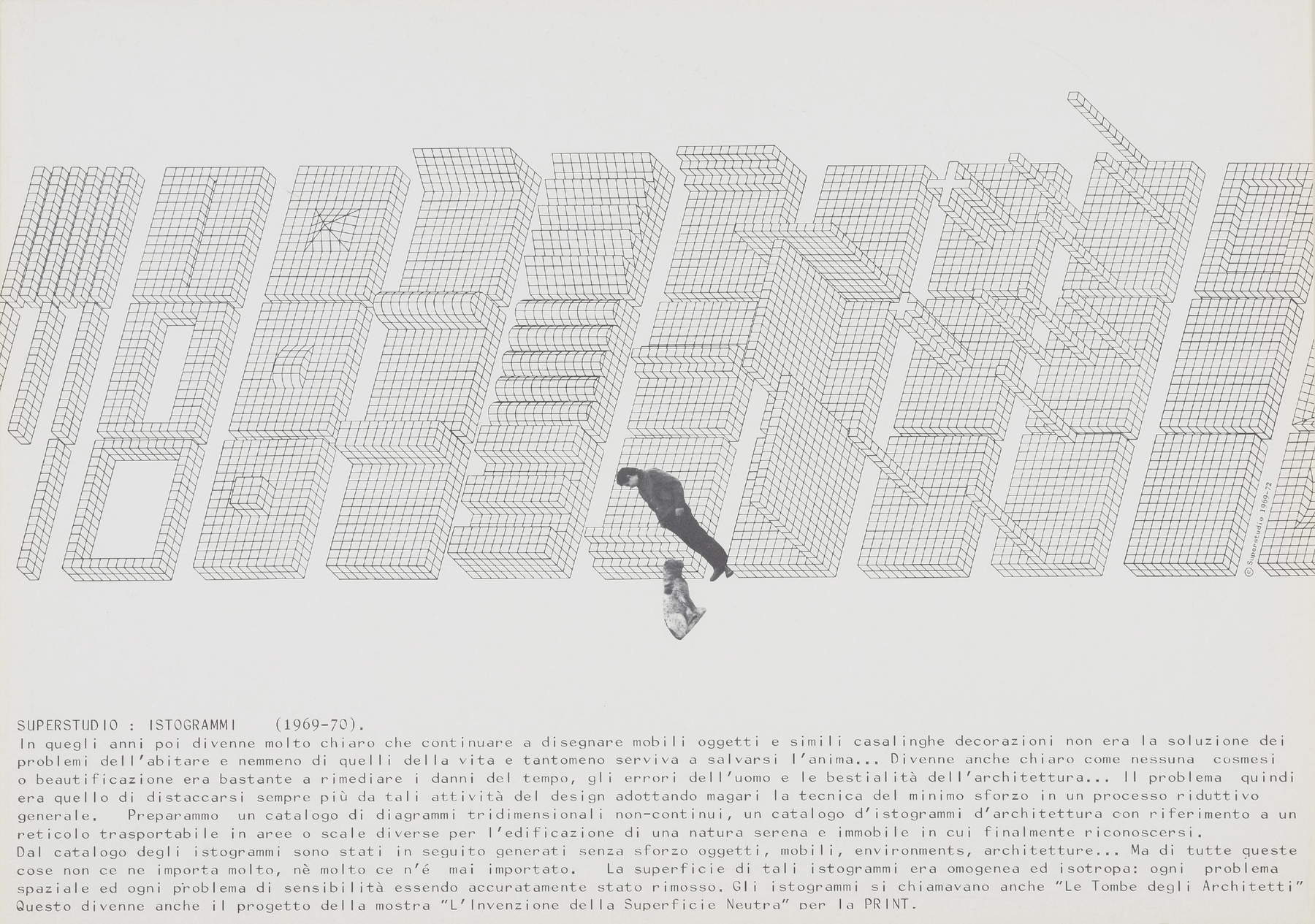

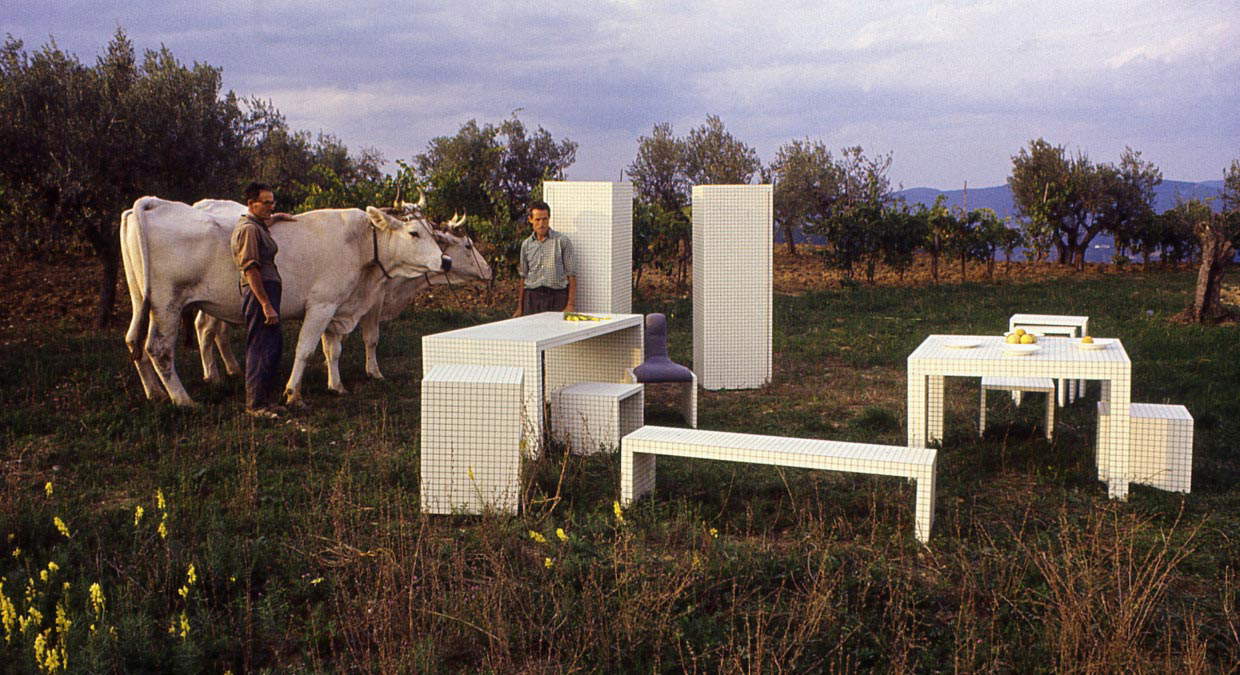

This is exactly how the Histograms of Architecture, a name coined by Edoardo Boncinelli, a geneticist and friend of the group, took shape and body in 1969. “Histograms” because they presented themselves as unfinished three-dimensional lattices, without a defined scale, of the “platonic, neutral and available entitiesÌ€.” They were in fact available to be assembled, to become raw material for the construction of a potentially infinite and continuous surface. They could take on an urban scale, as in the Catalogue of Villas, or a planetary dimension, as in the series of photomontages produced by Toraldo di Francia in which the Continuous Monument embraces the Earth and connects it with the universe. Conversely, the lattice could be reduced to a very small scale, a 3x3cm square, which is then “translated” into plastic laminate by PRINT. Starting from that small square, the group develops a collection of furniture (desks, tables, beds) called Misura. The project was in the first instance proposed to Cassina and Poltronova (a company that had already produced some “pop”-inspired furniture for the group, also in the late 1960s) but neither of them agreed to put into production such an abstract piece of furniture, which more than an object represented a “concept.” And indeed this was the case, as can be guessed from Adolfo Natalini’s writings: “we are only interested in ’mental furniture’: i.e.Ì€ objects to hold in front like a mirror, things to touch, to look at from near and far as exorcisms against confusion and unjustified consumption. We are interested in furniture for calm and serenityÌ€, constituent stones of a calm and still nature in which we can finally recognize ourselves.”

Those who instead answered Superstudio’s call, agreeing to produce the first prototypes, was Aurelio Zanotta, who grasped potential in the thought hidden behind these unusual and apparently simple objects. They in fact reveal how maximum freedom needs an order and a rule. In fact, what in the scale drawing of the furniture is a small square, when translated to an architectural or urban scale becomes an equipotential network that leads everywhere, in a world made up of connections and relationships, which develop in the “nodes” of the network; a network that connected humanity, long before the Internet was born.

The

The

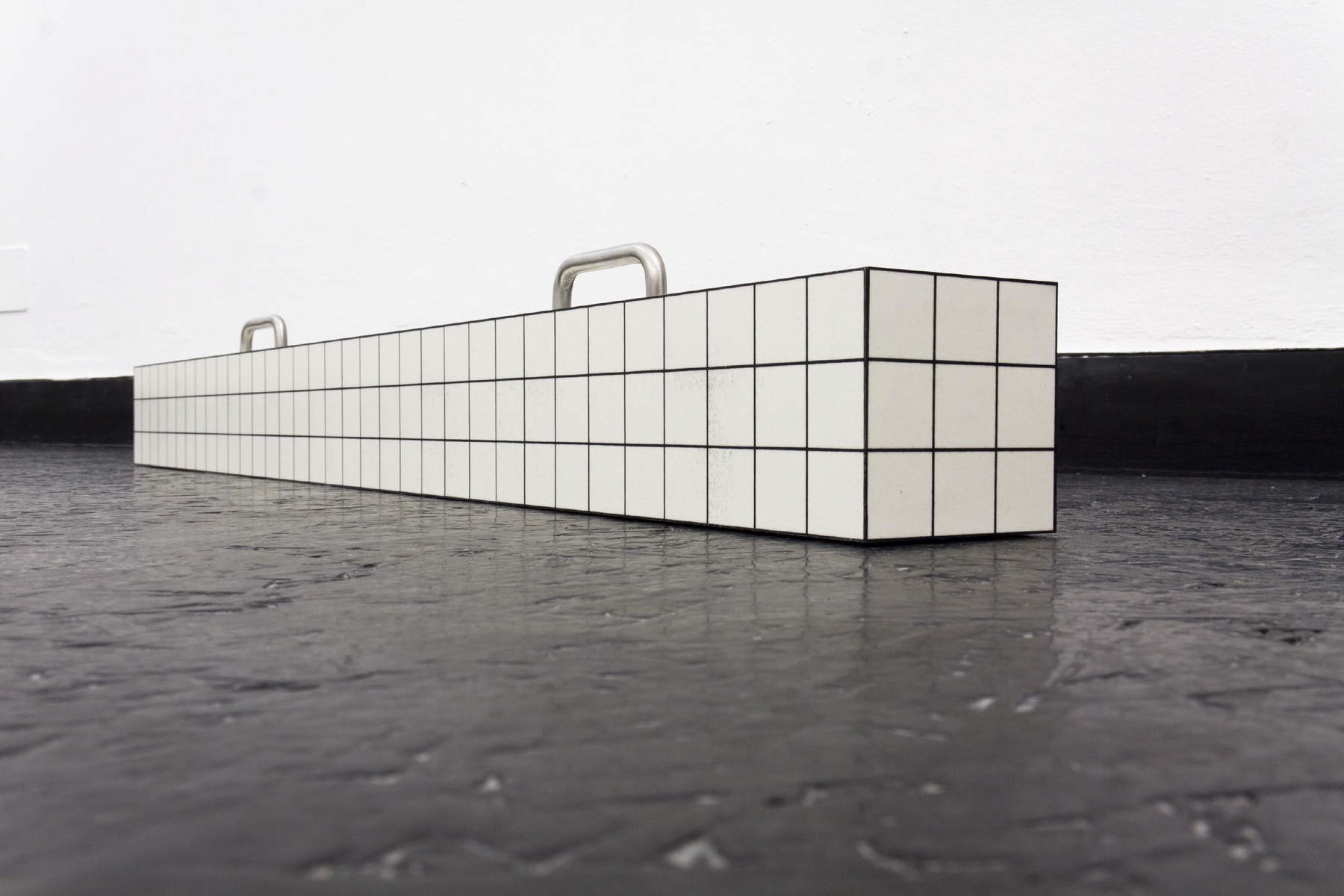

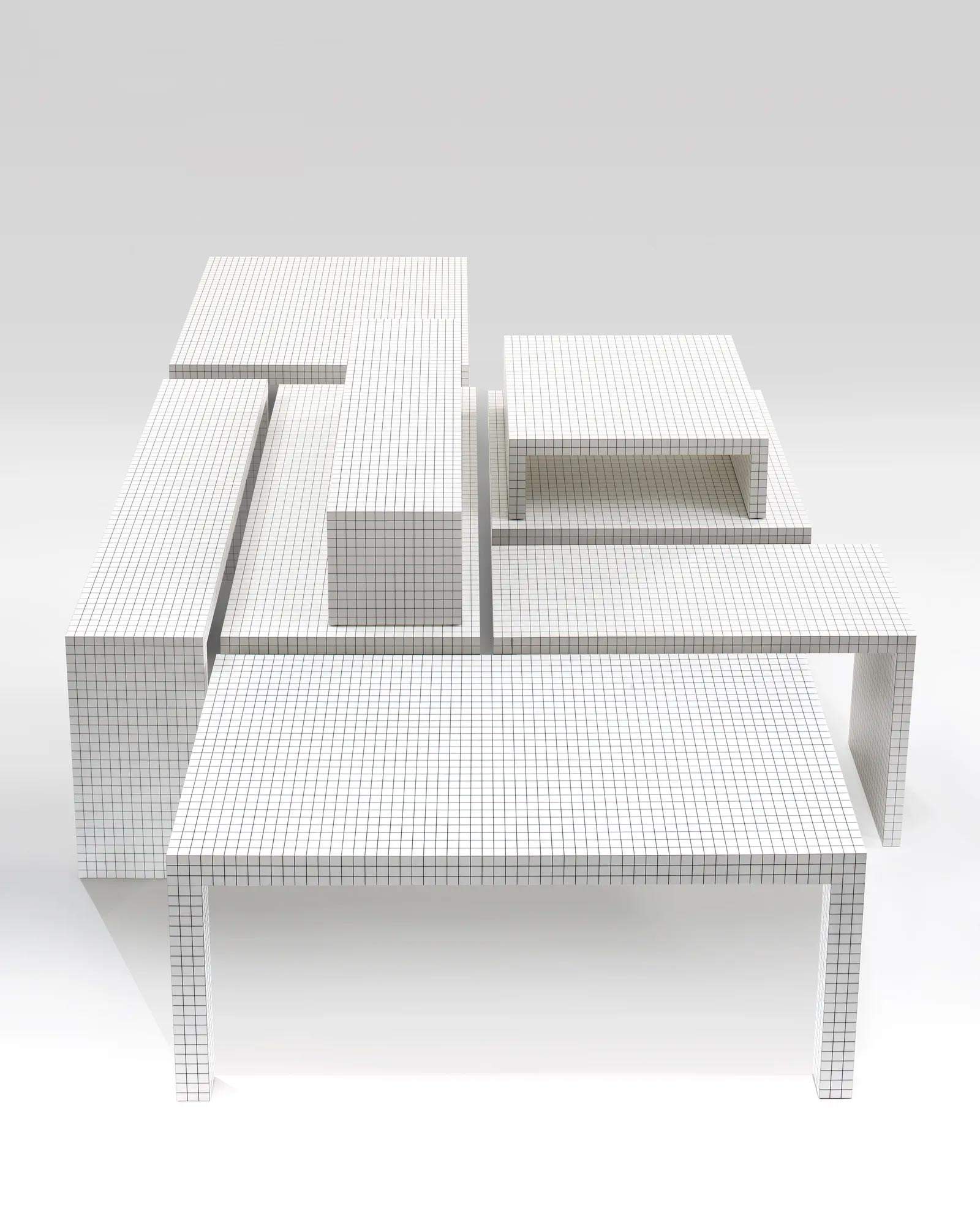

Thus it is that from the intuition of Superstudio, passing through Misura, the Quaderna series was born, put into production by Zanotta in 1972. It makes sense to talk about the entire series and not just one component precisely because of the idea that guides its creation: through architectural histograms, it is possible to create objects that have the same characteristics while occupying space differently. The architectural forms (as Superstudio understands them) that make up the original collection are three tables, the desk, the console table, and the low table. They are presented as “wooden furniture and objects covered in PRINT printed plastic laminate. The peculiarity of the pattern is that it is homogeneous and isotropic over the whole surface, so that it can be put in place according to the three main Cartesian directions” (Domus No. 517, December 1972).

Extremely original and complex is the production process, which is connoted as highly industrialized and at the same time artisanal. The lattice is made by digital printing, which causes a slight variation in the spacing of the lines and thus implies creating a body to be clad that is not perfectly orthogonal, so that all the lines on each side optically match. The laminate pieces are then applied individually: first the legs are coated along with the thickness of the top, then the outer faces and finally the top. This is an extremely precise craftsmanship that can take up to eight hours to make a single piece. Says Zanotta, "Each Quaderna object is created from a single sheet of laminate so that the spacing, even if misaligned by a few tenths, is the same: only in this way do the squared surfaces result continuous in the three dimensions oriented by the Cartesian axes in compliance with the original design.“ The difficulty in making the various joints coincide to the millimeter makes it impossible to detach the legs from the plane even during transport. ”An extra complexity, indispensable, however, to preserve the uniqueness of the original idea," the company claims.

Despite the complex process of its creation, the Quaderna series still remains relevant, and in the last two years it has been enriched with additional elements, made keeping true to the inspiring idea of Superstudio. This is undoubtedly the result of the group’s theoretical bearing, since with that fundamental unit, that small 3x3 square, one can potentially create anything; on the one hand objects that could be quietly useless and on the other hand very useful objects, which indeed manage to adapt to the needs of the contemporary world. It turns out that these two souls, perfectly embodied by Quaderna, are truly extraordinary: on the one hand, the potential creative freedom, the infinite possibility; on the other, the set of ironclad rules and procedures that concur in the creation of the object.

They echo the words of Superstudio: "the greatest project is always to design ourselves a whole life under the sign of reason, a life with precise, and serenely accepted, coordinates. To build ourselves with a series of primary gestures, of calibrated and lucid magical gestures, by means of an architecture of clarity and lucidity, not of cruel intelligence but of the understanding of all reasons...." Undoubtedly to this day, Quaderna is an ambassador of these words and thought, continuing to embody and communicate them, keeping the past and the present in constant dialogue, always with an eye to the future.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.