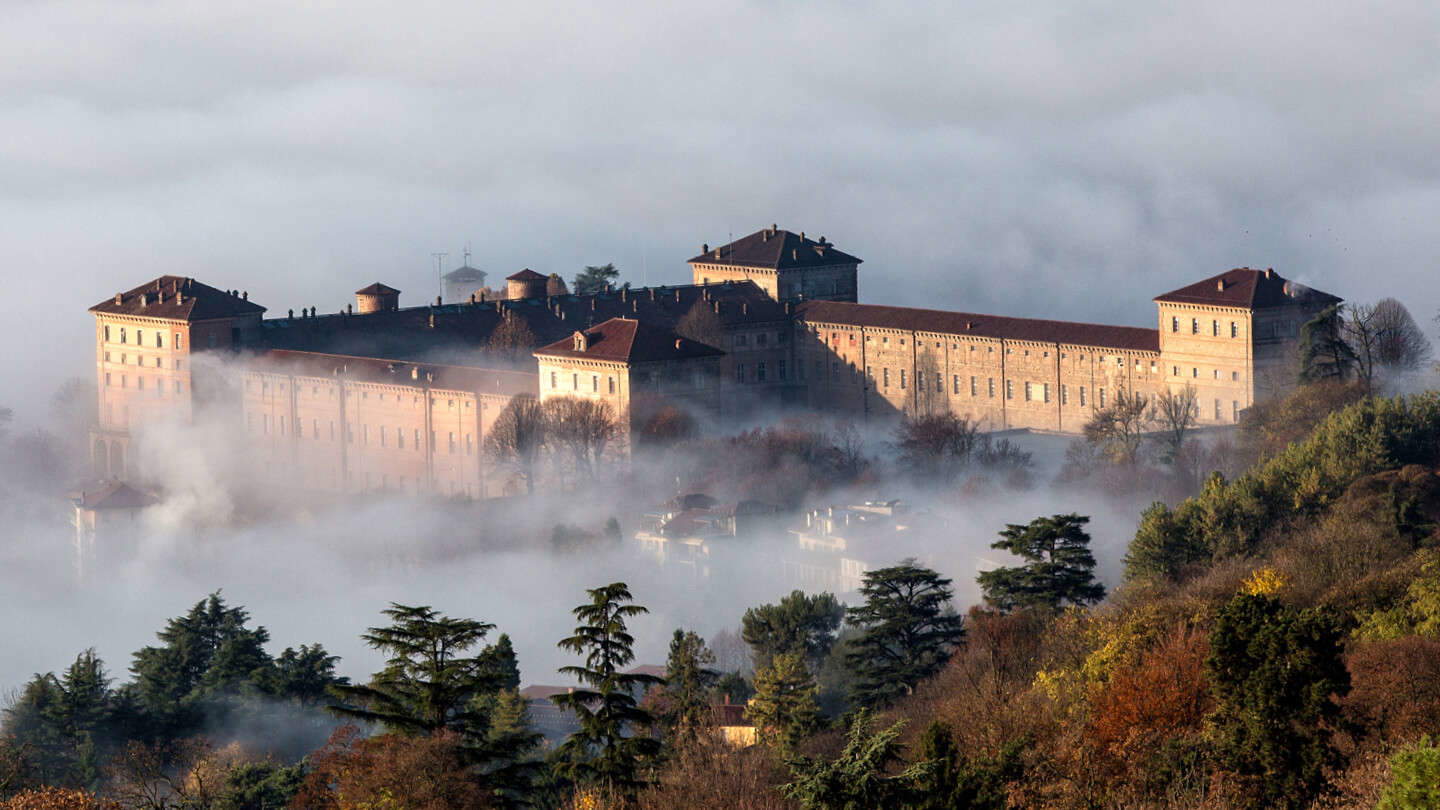

A half-meter hole in the woodwork, plaster surfacing under the wood, the jambs blackened by the marks of the flames that rise and engulf, engulf, devastate. Restorers wanted to leave clearly visible, in the room that precedes Victor Emmanuel II’s dressing table, one of the marks left by the fire that devoured the southeast tower of Moncalieri Castle on April 5, 2008. Smoke rising past the ceilings and billowing out of the windows, flames creeping into the rooms, engulfing and burning, one by one, the tower’s halls, the fire smothering pieces of Italy’s history. Lost is the king’s bedroom. Lost the Queen’s dressing table. Lost the ceiling of the Queen’s Bedroom. Lost the Proclamation Room. And that is the room where, on November 20, 1849, a not yet 30-year-old Victor Emmanuel II pronounced the manifesto, written together with Massimo d’Azeglio, with which he announced the dissolution of the chambers of the Kingdom of Sardinia and urged voters to consider the interests of the state. Which, by implication, meant voting for a majority inclined to ratify the Peace Treaty with Austria after the First War of Independence. Where a page of history had been written, only ashes remained.

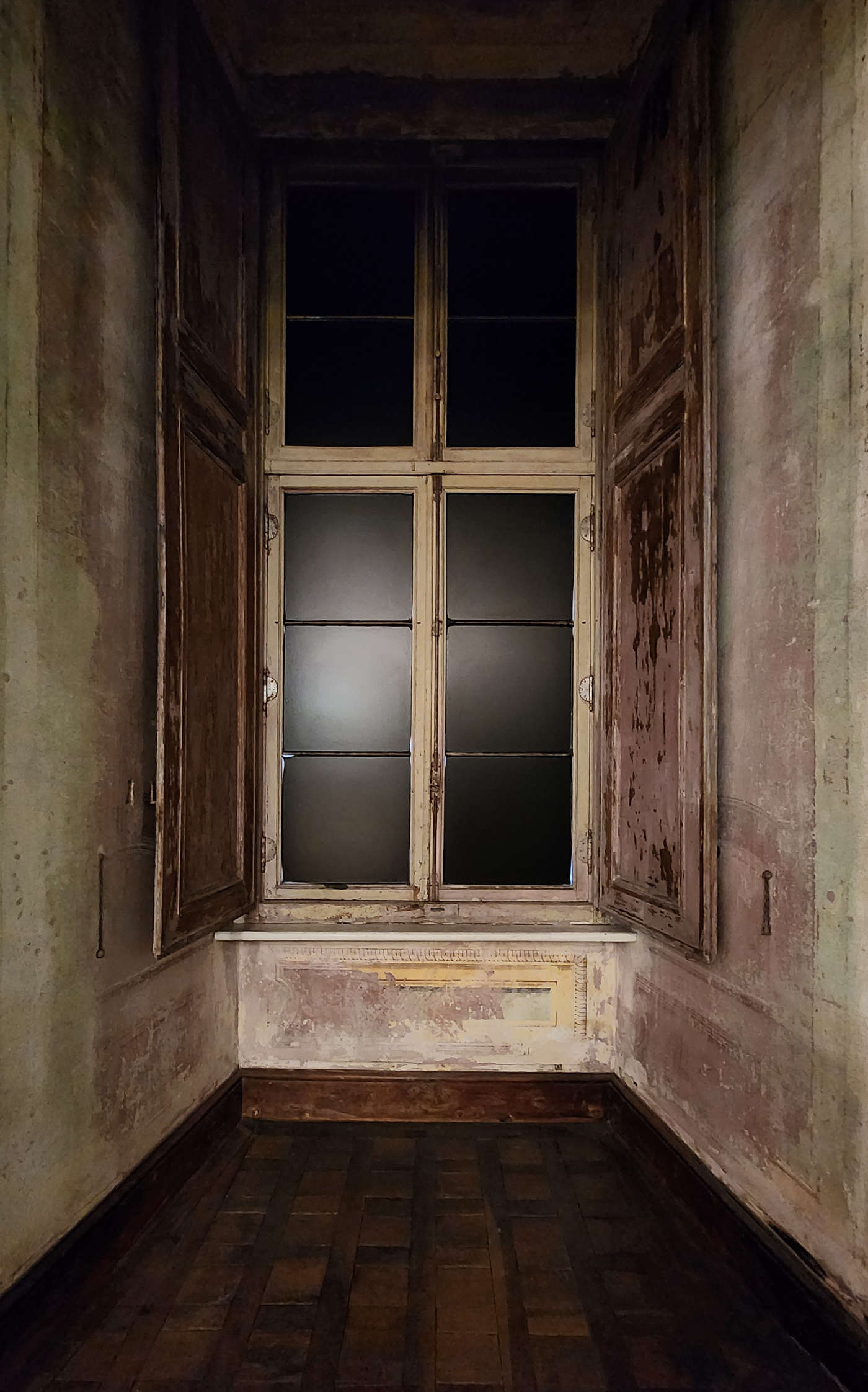

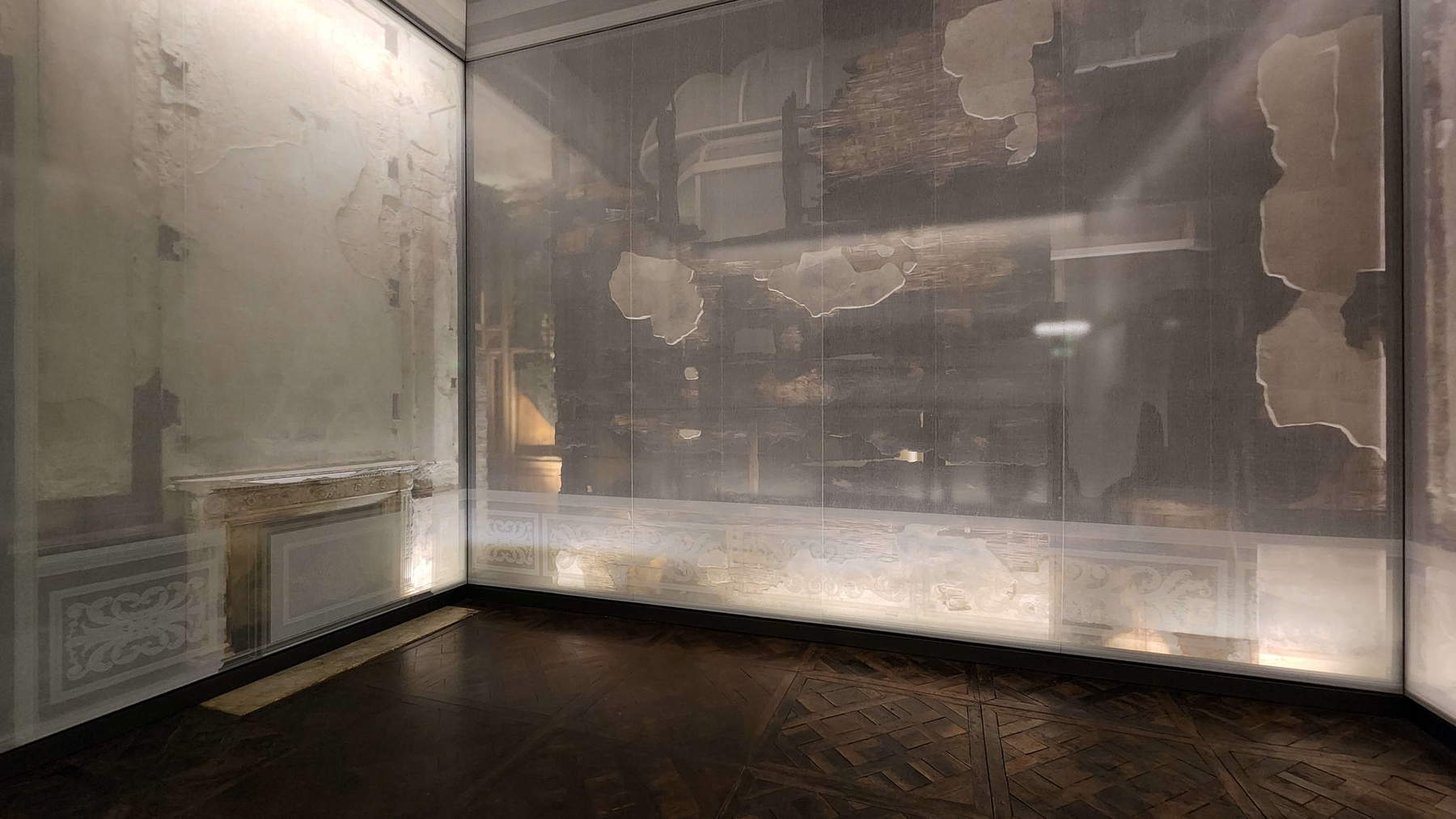

“Ten million euros in damages”: so headlined the newspapers, croaked the radios, repeated the television news reports. As if a sum of money could restore what had been lost forever between fire and water. The truth is that the damage was irreparable, and three rooms of Moncalieri Castle no longer exist. Those three rooms would be open to visitors again after nine years: nine years of work to restore what could be restored and to refit the lost rooms so that everyone could see what happened, here, one clear-sky spring morning. Three rooms impossible to reconstruct because too few archival and photographic records were available. Nevertheless, the architects who oversaw the arrangements, Maria Carla Visconti and Beppe Merlano, had a sharp and poignant idea: Consolidate the charred elements, and then leave the ruins exposed, let visitors see the flayed plasterwork, the tarnished bare, the fragments of ancient frescoes that survived beneath the flame-eaten nineteenth-century papier peint , yet evoking the lost decorations with a product from the French company Barrisol, namely backlit transparent sheets capable of suggesting the shadow of what the stake erased forever. Moncalieri Castle is the only one where ghosts can actually be seen.

They were among the most fascinating rooms in the castle. Among the most luxurious, among the most colorful. Especially the queen’s dressing table: a small room entirely covered with mirrors, able to reflect the glow that entered through a glass door, bathing the whole room in light. Perhaps the whole could have appeared excessive, boisterous. But it is a sensation that nevertheless one still feels now, wandering around all the rooms of the royal apartments, where Victor Emmanuel II and his wife Maria Adelaide lived, now open for visits, becoming everyone’s heritage. One arrives at the apartment from the grand monumental staircase, which leads toward the dining room, an all in all still quiet environment. One passes through some service rooms, and then the rooms lost in the fire, and arrives at the queen’s bedroom.

Scarlet upholstery, a gilded ebony frieze from the work of craftsman Gabriele Capello, a door that opens to reveal a tiny private chapel with an ivory crucifix under a canopy similar to the one that tops the queen’s bed, and then, clashing with the’charged uniformity of the room, the spectacular Meissen porcelain vase by Johann Joachim Kandler, a triumph of color, of executed snowball flowers, stems, leaves and creepers, even a few little birds chirping contentedly, beginning with the canary that towers over the entire composition.

The Blue Drawing Room, the Queen’s former entertainment room, is even more pompous and fractious. Domenico Ferri, the director of the apartment’s decoration, wanted to evoke in his own way a Rococo taste that the France of Napoleon III had exhumed, brought back into vogue. Of sobriety there is very little. A sense of supreme horror of emptiness prevails. Blue damasks are enclosed within fanciful ebony chiambranes, each with small painted porcelain ovals (one, lost, has been replaced with the same image, but blurred). Tortuous lines for the papier mâché frieze running along the walls. A network of gilded frames cages the ceiling roundel, which imitates an opening to a blue sky. The door overlays, with putti playing amid flowering lawns, are almost barely distinguishable amid all this crowding (and there was even more stuff in the old days: some of the furniture, 18th-century works executed by Pietro Piffetti for Charles Emmanuel III and transported here at the time of Victor Emmanuel II, is now at the Quirinale). There is also a lofty fireplace parure, with clock and two candelabra, all covered in gleaming gilding, the work of Parisian watchmaker Paul Garnier. The adjoining Sala del Convegno is more restful, but if you try to look up, you are immediately captured by the swirling ceiling: the illusion of a dome rising above the gilded cornices, above monochromes with allegories of the greatest cities of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Turin, Genoa, Chambéry, Cagliari.

It was especially in these environments that Domenico Ferri’s project focused. Transforming the portion of a wing of Moncalieri Castle into an eclectic fantasy that looked to the France of the Second Empire. The Savoy had intercepted with curious precocity the fashion that was emerging on the other side of the Alps: Napoleon III had taken office in 1852, and Ferri was beginning to design his Rococo revival in 1852. Ferri’s rooms are also the ones that have remained most intact in the last century, after the Savoy family abandoned Moncalieri Castle.

For a long time, even after the proclamation of the Unification of Italy, the Savoy family lived in here. Some might have preferred not to: Moncalieri Castle was the place of imprisonment of the first king of Sardinia, Victor Amadeus II, imprisoned following his attempted coup against his son, Charles Emmanuel III. The castle had been Vittorio Amedeo’s favorite residence, but it was also his last forced abode. For others, however, it was always a pleasant place. Victor Emmanuel II would often stay here even after the conquest of Rome, even after the monarchy had elected the Quirinal as its first residence. Still others spent within these walls a resigned, secluded, modest life, far from what one would expect from those in a royal household. Chronicles from the late 19th century tell us that Marie Clotilde, eldest daughter of Victor Emmanuel II, considered the apartment she had been assigned, on the other side of the castle, too large. She had apparently quarreled with her brother, King Umberto I, because she would have preferred something more humble.

One breathes a different air in this row of halls. There is not the slightest trace of the eccentric taste of Clotilde’s parents. It doesn’t even look like the apartment of a princess. Far from it. Five rooms on the second floor of the Castle, sober, severe, unadorned: they look like the rooms of a middle-class home of the time. Enlivening them are only a few landscapes by Piedmontese painters of the time: one sees works by Filiberto Petiti, Mario Viani d’Ovrano, Pietro Sassi. They are indicative of the attention the Savoy family paid to contemporary art. However, we do not know where they were originally, since Marie Clotilde’s apartment and the one on the first floor, the apartment of her daughter Maria Letizia Bonaparte, have been modified over the years. Certainly, Marie Clotilde’s bedroom was not supposed to have the plaster cast that can be seen today: it is the model of the sculpture that depicts her in the act of praying, kneeling, and that was installed here after there were plans to turn what had been her bedroom into a sort of small mausoleum, a project that never came to fruition. A small monument that Pietro Canonica waited for in 1912, after the princess’s passing. The marble is preserved not far from here, in the historic center of Moncalieri, inside the church of Santa Maria della Scala. Clotilde has gone down in history as the “saint of Moncalieri.”

She was a woman of pious, devout temperament, a deeply religious woman. She was married to Napoleon III’s cousin, a man of a totally different character from her own, a man she would not have wanted. Clotilde had the courage to express her opposition to the planned marriage even to Cavour, and she was only fifteen years old: in the end she accepted not so much out of political calculation or to please the royal house, but because she thought that was the destiny to which God had called her. It was not a very successful marriage: after the fall of the Second Empire, despite her desire to stay in Paris (she thought that was where she belonged, and that staying in France was her duty), she was persuaded to leave the capital. A few years in Switzerland, and then a move to Moncalieri, without her husband, from whom she had separated. And once here, the final decision: to retire to private life for the rest of her days. In one of her letters she had put down on paper her will to immolate her whole life to the love of Christ (the verb “immolate” is Clotilde’s: therefore, this sense of sacrifice was hers as well). For her, the family residence became a “cloistered castle,” as a journalist of the time titled it. The Savoy family has long hoped that someone would make her a saint. In the Vatican, the cause of beatification is still open.

So different from her, however, was her daughter Maria Letizia, who lived in the first floor apartment. She loved her mother, whom she considered her best friend. But unlike her, she liked to lead a social life. In order to go upstairs to her mother, without having to take the stairs each time, Clotilde had an elegant elevator made of wood, glass and brass, with a decorated cabin, designed by the Sagler company, and which is still in operation today, and with the original motor. We do not know the exact year, but it dates from the early twentieth century. You can see it after going through all the rooms of her apartment: Maria Letizia went to live inside rooms that had already been lived in in the 18th century (and the ceilings are partly those of the time: the princess did not want to touch them). The young Bonaparte, cheerful, rebellious, lover of the good life, had had an elegant, fine space set up for her, with delicate tones: the only room that has remained substantially intact, however, is her bedroom, purchased in 1910 from the furniture maker Giacomo Borra. Next to the room was also an eighteenth-century Chinese cabinet, of which almost nothing remains: a lacquered door, and a painted vault. That, however, has nothing to do with China. Instead, the rest is the result of rearrangements on what had survived from the eighteenth century (the overlays, for example), or rearrangements, made sometimes with relevant furniture, other times with things that we might not imagine inside the apartment of a princess. Like the equestrian portraits of the Savoy family in the elevator room, for example (which, in fact, come from the Venaria Reale). They match the portraits of kings and emperors that, in Vittorio Emanuele II’s apartment, decorate the room that leads to the dining room.

After Maria Letizia, silence fell over the apartments of the king, queen and princesses. The Savoy no longer needed the residence that had been a medieval fortress, built by Thomas I of Savoy in the 12th century, that had been a pleasure villa in the 15th century, that had been a king’s prison, that had been barracks during the Napoleonic occupation, that had returned to a sumptuous residence when the Savoy returned there with Victor Emmanuel I. When World War I was over, Victor Emmanuel III had wanted to dispose of some of the residences the household had inherited: after the Unification of Italy, it had become all theirs. The palaces of all the princes, of all the kings who had administered pieces of Italy over the centuries had become the patrimony of the Savoy: too much stuff. So, after the war, the king gave up some of his royal villas and some of his castles for the benefit of veterans. “The gift of kings to good soldiers,” Emporium magazine titled. There were places like the Villa Reale in Monza, the Coltano estate in Tuscany, the Villa Medicea in Poggio a Caiano, the Royal Palace in Caserta. And there was Moncalieri Castle, the only one of the Savoy residences included in the divestments. Although it had been a place many of the family members had been fond of.

It was necessary, however, to wait until Maria Letizia’s death in 1926 for all the transitions. The following year a school for army officer trainees was installed there. Then, after World War II, in 1945, the complex became the property of the Carabinieri: to this day Moncalieri Castle is still their barracks. And now it lives this dual condition of military garrison and museum, managed by the Ministry of Culture, which has become the owner of the apartments. The opening to the public in 1991. The fire of 2008, the fire offending the tower, the castle, the history. The long closure to fix the damage, to put the pieces back together. The reopening. The voices of the guides, the footsteps of visitors who, every weekend, resound there where once the voices were heard, the footsteps of the first king of Italy, his wife, then his daughter, then his granddaughter. The new life, public and quiet, of the ancient home of kings.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.