Stane Kumar, the Slovenian artist who drew children interned in Italian concentration camps

From the moment it was established, now twelve years ago, Remembrance Day has in fact cleared the most boorish and petty neo-fascist propaganda, for which it would seem that there is no memory resulting from the combination of all the events that occurred in the past, but only a handful of disjointed memories, the contextualization of which in broader scenarios is an operation to be carefully avoided. It is truly disheartening to think that on the sad events of the dead and refugees one can cannibalize history and make propaganda: we have witnessed depressing ideological clashes, to say the least imaginative revisitations of the past, instrumental uses and manipulations of events and testimonies (only the example of the numerous images falsely traced back to the massacres of the foibe, on which the Wu Ming collective has done incessant work, is worth mentioning). However, we do not want to go into historical reconstructions on a very difficult subject such as the foibe: let us leave that task to historians. But neither can we tolerate that the solemnity of the “Day of Remembrance” passes without the remembrance being contextualized.

It is necessary to start from a point on which light is beginning to be shed: it is not correct to speak of ethnic cleansing (a term, moreover, which entered common usage in the 1990s of the last century) to the detriment of Italians for the foibe massacres. As historian Enzo Collotti recalled in an article that appeared in the Manifesto in April 2000, among those who lost their lives in the foibe massacres “there were certainly many innocent people but also many people responsible for massacres against Slavs and anti-fascists. Not wanting to distinguish between these different categories of subjects and wanting to homogenize all of them as victims of an inexplicable violence referable only to anti-Italian fury, entails serious political consequences.” Conversely, of"national reclamation“ spoke a circular letter sent, in 1931, by the Ministry of the Interior to the prefects of Venezia Giulia, in which the expropriation of ”landed property which, in a border area, of an amplitude to be determined, is now found in the possession of allogens." By the term"allogeni," the fascist regime referred to the ethnic non-Italian populations inhabiting Venezia Giulia and Dalmatia.

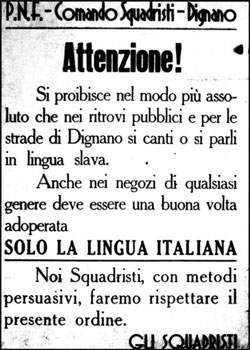

|

| Fascist manifesto for the forced use of the Italian language in Vodnjan, Istria |

Fascist Italy, in other words, operated an attempt at the rationalization of ethnic minorities, adopting strongly discriminatory measures against Slavic populations: a ban on speaking in the native idiom and the compulsory use of Italian, the Italianization of place names and surnames, the closure of foreign-language newspapers and, in general, of activities in which Slavic idioms were used, and, of course, squadrist aggressions against Slovenes and Croats who did not abide by the “rules.” The repression was brutal, and reached dramatic outcomes in the course of the war, especially following the Italian occupation of what would later become the province of Ljubljana. In this context, General Mario Roatta, destined to become a war criminal, issued the infamous Circular 3C on December 1, 1942, which contained strongly repressive measures against partisans and even the civilian population. With regard to the latter, the possibility was established to “intern, by way of protective, precautionary or repressive measures, families, categories of individuals from the city or countryside, and, if necessary, entire populations of villages and rural areas,” to “stop hostages drawn ordinarily from the suspected part of the population, and, - if deemed appropriate - also from its entirety, including the higher classes,” and to “hold co-responsible for sabotage, in general, the inhabitants of houses close to the place where it is carried out.”

In order to receive civilians rounded up from their homes, Fascist Italy had set up a number of concentration camps located along the eastern border: among them was the Gonars camp, built in 1941 in the Friulian town of the same name, a few kilometers from Palmanova, and initially used for the purpose of internment of prisoners of war and political dissidents. The latter included all those Slovenian and Croatian intellectuals who strongly opposed both the fascist regime and its policy of forced Italianization. In Gonars, in particular, a large number of Slovenian intellectuals of the time were interned, some of them at the beginning of their careers: thus, in the lists of prisoners we find writers (Vitomil Zupan, Bojan tih), poets (Alojz Gradnik, France BalantiÄ), historians (Bogo Grafenauer, Vasilij Melik), scientists, politicians, journalists and, of course, artists. Among the latter, perhaps the best known names are those of Nikolaj Pirnat, Jakob Savinek, Nande Vidmar, Drago Vidmar, Vlado Lamut, and Stane Kumar. It is precisely on Stane Kumar (1910 - 1997) that it is interesting to dwell: his drawings are one of the highest and at the same time heartbreaking testimonies to the tragic conditions of the innocents interned in Gonars.

After the issuance of Circular 3C, entire families from the Slovenian territories occupied by the Italian army arrived in Gonars en masse. The presence of elderly people, women and especially children began to become particularly intense. At the same time, the artists interned in Gonars began to produce a variety of drawings to tell what life was like in a concentration camp-a particularly fortuitous occurrence, since in other lagers artists had not been able to have the same opportunity. In fact, the Gonars artists had the good fortune to meet Mario Cordaro, the concentration camp doctor (to whom, moreover, the Gonars municipality has dedicated a square), who managed to offer the prisoners unexpected glimmers of humanity: he cared for the sick, tried to save the lives of prisoners who seemed to be scarred by now, and promoted the activities of Slovenian artists imprisoned in the camp. The story, moreover, is retraced in an exhibition entitled Beyond the Wire. Traces of memory from the Gonars concentration camp, running until Feb. 14, 2016 at the Church of San Lorenzo in San Vito al Tagliamento. A summary of what happened in the camp was offered to us in an article by Simonetta D’Este published in Messaggero Veneto on January 27, 2016: Mario Cordaro “found a way to create a bond with the interned artists, trying to alleviate their suffering by bringing the material for painting: he approached them under the pretext of having them collaborate in the infirmary, and here they could find food and the possibility of expressing their art, which in the drawings made tells of the suffering of internment, lack of freedom, physical suffering and deprivation.”

As anticipated, Stane Kumar devoted himself precisely to depicting the children locked up in the camp: many of these drawings are now preserved at the Muzej noveje zgodovine Slovenije, the National Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia, located in Ljubljana. In a 1943 work, Internirani otroci (“Interned Children”), signed and dated (“S. Kumar 43 / Gonars”), the artist gives us an idea of how children were forced to cope with the harsh conditions of imprisonment: in worn-out clothes, without footwear, in disastrous hygienic conditions, forced to wander around the camp as they were often orphaned by their parents, who were not infrequently shot during summary executions by the fascists against the Slovenian and Croatian populations, or died of starvation due to the atrocious living conditions in the camps. Slovenian historian Metka GombaÄ offered an insight into the situation of children interned in Gonars and other Italian concentration camps in her 2005 article in a scholarly journal of the University of Venice, Deportate, Esuli e Profughe (of which we provide full entry and link to download it in the bibliography). Children were precisely the main victims of the conditions in the camps, particularly that of Rab-Arbe, where the highest death rates were recorded. Often, camp commanders purposely avoided improving living conditions: planning for insufficient food, notes Metka GombaÄ, was functional in order not to take resources away from the army and to make the prisoners weaker. “One does not condemn to death, therefore, but allows to die.”

|

| Stane Kumar, Internirani otroci, “Interned Children” (1943; Ljubljana, National Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia) |

|

| Stane Kumar, Internirani otrok, “Interned child” (1943; Ljubljana, National Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia) |

Kumar himself was awed by the sight of these children, who, tried by suffering, wandered around the camp, especially after several prisoners from Rab-Arbe arrived in Gonars at the end of 1942 (the move had become necessary partly because of the continued arrival of new internees from Slovenia, and partly because living conditions in Rab-Arbe had deteriorated tremendously). A further drawing by Kumar, one of the most poignant of his production, depicts a skeletal child leaning sadly against a barbed wire: he is crying, and in such pain that he seems not to notice the pain caused by the thorns. And no matter how schematic the work may appear to us, no matter how uncertain the stroke may seem (we have to imagine, after all, under what conditions the artist had to operate: and if we think about that, we cannot but pay all our admiration to Stane Kumar, who despite the sufferings of the camp still managed to find the strength to do what he loved), the drama and tragedy of the camps and the war appear to us in all their violent ruthlessness. It is also a drawing that almost seems to give shape to the thoughts of Kumar, who in one of his memoirs, taken from a document preserved in theState Archives of the Republic of Slovenia and quoted in Metka GombaÄ’s article, recounted this impression: “I saw the hunger of World War I, but that was not real hunger. The really real one was hunger in the camps where at every step you would find two pairs of eyes asking you to feed them, to give them something to eat. The children would become dull and sit in the corners of the shacks without speaking. So many were dying of hunger and you couldn’t do anything.”

|

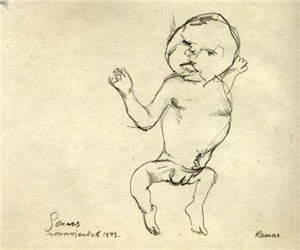

| Stane Kumar, NovorojenÄek, “Newborn Child” (1943; Ljubljana, National Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia) |

It is somewhat difficult to determine the number of children who ended up locked up in the Italian concentration camps on the border: they were not noted in the official registers, and the births that occurred within the camp perimeter were not marked either. Kumar himself left us, among his many drawings, a sheet depicting a newborn child: it is known as NovorojenÄek (“Newborn Child”: the artist himself wrote the title directly on the sheet) and, like almost all the drawings made by Kumar in Gonars, bears the artist’s signature in addition to the date and place of making. We can only speculate as to what the fate of many of these infants was: the camps were obviously not equipped to allow decent conditions for women in childbirth, and these children were the victims most exposed to hardship, to the numerous diseases that spread among the prisoners, and to starvation, not least because their own mothers lacked the nourishment with which to feed them. It is therefore likely that the same fate befell the child depicted by the artist, also in view of the fact that infant mortality was extremely high: most babies born in the camp did not make it beyond the first few days of life.

Stane Kumar was among the survivors, but many of the internees did not make it out of Gonars alive. Children were among the most numerous victims: however, as mentioned just above, it is not known how many children were imprisoned in the Italian concentration camps on the border, nor is it known exactly how many of them perished. Limiting ourselves to Gonars, we can cite Boris Pahor, who in his recent book Red Triangles, speaks of 453 men who died in the camp, to which he adds the 953 women who, according to his reports, lost their lives in the women’s section. Although the figures fluctuate (there are even those who stop the count at 453), they all more or less agree on establishing around five thousand people as the number of those who, on the date of the armistice, September 8, 1943, were locked up in Gonars. Historian Alessandra Kersevan has estimated the exact number of internees in Gonars at 5,343 people, including 1,643 children, based on a document dated February 25, 1943 and written in Slovenian by a relief committee for the internees in Gonars. Today, the camp no longer exists: after the armistice, dismantling began, which was quickly completed. What remains, then, today of one of the most shameful pages of Italian history of which many, unfortunately, have no or little knowledge? What remains are the testimonies of many former prisoners, often transcribed immediately after the war (particularly moving are precisely those of the children: several were collected by Metka GombaÄ in the work we mentioned), what remains is a shrine erected in 1973 in the cemetery of Gonars in memory of those who lost their lives in the camp, what remains is the commitment of the inhabitants of the Friulian municipality to keep the memory alive. And there remain, of course, the drawings of Stane Kumar and the other interned artists: also strong testimonies, capable of communicating with strong impact a page of history whose memory should be more alive than ever on days dedicated to remembrance and remembrance. And a memory that remembers everything is the best way to truly pay tribute to all the innocent victims.

Reference bibliography

- Boris Pahor, Red Triangles: The Forgotten Concentration Camps, Bompiani, Milan, 2015

- Arturo Benvenuti, K.Z. Drawings of internees in Nazi-Fascist concentration camps, Becco Giallo Editore, Padua, 2015

- Gianni Oliva, Foibe, Mondadori, Milan, 2014

- Joe Pirjevec, Gorazd BajÄ, Foibe: a history of Italy, Einaudi, Turin, 2009

- Adamo Mastrangelo, Foibe, what is not said, Lampi di stampa, 2009

- Metka GombaÄ, Slovenian children in Italian concentration camps (1942-1943) in Deportate, Esuli e Profughe, no. 3, July 2005. The contribution can be downloaded in PDF format from here

- Alessandra Kersevan, A fascist concentration camp: Gonars 1942-1943, Kappa Vu, Udine, 2003

- Boidar Jezernik, Joe Deman, Struggle for survival: Italian concentration camps, Drutvo za preuÄevanje zgodovine, literature in anthropologije, Ljubljana, 1999

- Milica Kacin Wohinz, Joe Pirjevec, History of Slovenes in Italy: 1866-1998, Marsilio, Venice, 1998

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.