by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 17/06/2018

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Women who used restrained and elegant makeup, men who shaved and attended beauty salons: we discover the world of cosmetics, makeup and beauty according to the Etruscans.

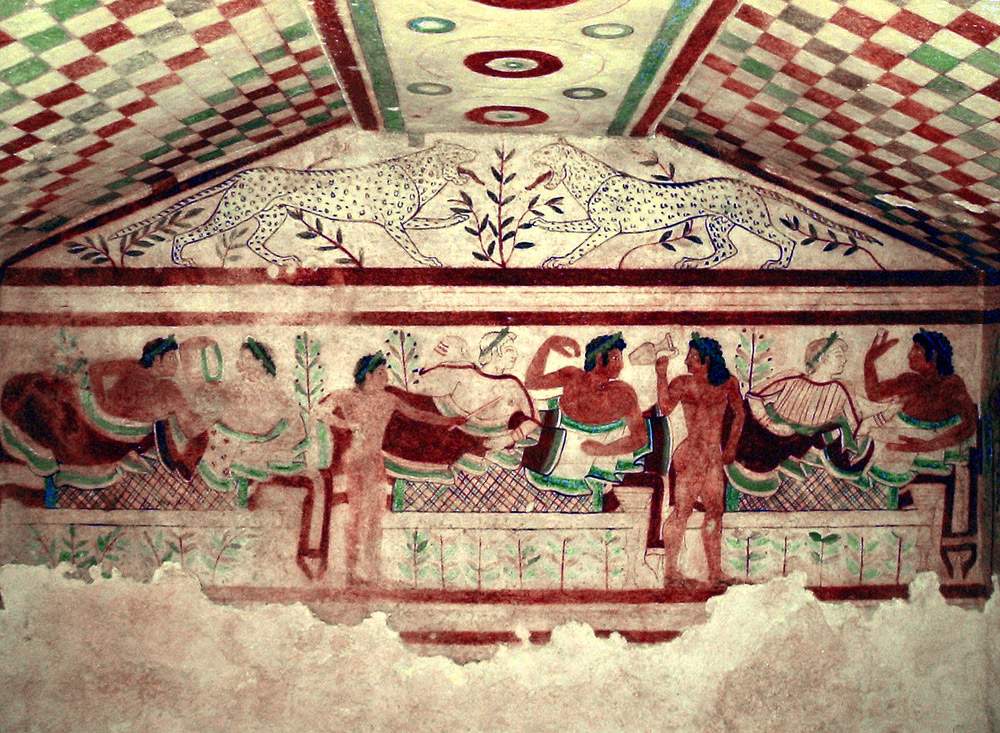

Among the characters participating in the banquet depicted on the walls of the Tomb of the Shields in Tarquinia, one can observe some elegant ladies sporting well-groomed blond hair, which contrasts with their dark eyebrows. Similar figures can be found in other Etruscan frescoes, and one can start from this detail to embark on a journey into Etruscan cosmetics: the Etruscans, in fact, spent a great deal of time taking care of their bodies and their image, and we have received a great deal of evidence that can confirm how much the Etruscans cared about their appearance. Observing the blond hair of the ladies of Tarquinia, some scholars have speculated that among the Etruscans there was a custom of... “oxygenating” their hair: probably, the Etruscologist Arnaldo D’Aversa has hypothesized, Etruscan women made use of lye, a liquid solution based on ash and water that in ancient times was used as a detergent, to clean rooms or for personal hygiene. Because of its bleaching properties, some peoples used it to wash or dye hair: the use of lye is known among the ancient Greeks precisely as an ancestor of the modern shampoo, while the practice of “oxygenating” hair was typical, for example, of the Gauls, as Pliny attests in his Naturalis historia, claiming that “soap” (Pliny, for the first time, uses the term sapo) was an “invention of the Gauls to make hair red,” which was obtained “from fat and ashes,” and which came “in two ways, thick and liquid.”

Given the extent of this fashion among the Etruscans (at least judging from the evidence that has come down to us), and given that specific skills were needed in order to achieve good results in the operation, it has been suggested that real beauty salons, or at least professional beauticians, were active in ancient Etruria, since, scholar Giovannangelo Camporeale notes, again in the Tarquinia frescoes men also have very well-groomed hair: short curly hair, cut at the same height, just below the base of the neck (and that this was not a stereotype of the artist can be deduced from the fact that the characters, observe for example those in the Leopardi Tomb, are distinguished by some, albeit minimal, elements of individual characterization). Providing some confirmation of the existence of beauty institutes in Etruria is the Greek historian Theopompus, who lived in the mid-fourth century B.C. and was always very harsh toward the Etruscans (he is best known for his scornful judgments of Etruscan women). “All the barbarians living in the West,” wrote Theopompus, “shave themselves using pitch and shaving with razors. Among the Etruscans there are several workshops with craftsmen who specialize in this activity, just as we have barbers. The clients of these workshops lend themselves to everything and are not ashamed of those who look at them or those who pass by.” Interestingly, the Etruscologist Massimo Pallottino has translated the original Greek term used by Theopompus, “ergastéria” (literally “workshops”) as “beauty institutes”: evidently, if we had found ourselves passing by, the impression we would have had by visiting these activities would not have been so different from that of today’s beauty institutes.

|

| Etruscan Art, Banquet Scene (third quarter of 4th century BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Shields) |

|

| Etruscan Art, Banquet Scene (third quarter of 4th century BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Shields) |

|

| Etruscan Art, Banquet Scene (473 BC; fresco; Tarquinia, Tomb of the Leopards) |

Body care was therefore an activity that interested women as well as men. As for men’s tools, the Etruscan man’s trousseau did not lack a razor, which had a strange half-moon shape, invented by the Etruscans and useful so that the blade would better fit the features of the face: in our archaeological museums (here we include a couple of examples from the Archaeological Museum of the Maremma and the Museum of the Territory of Bolsena) several examples of lunate razors (this is the term by which such a tool is referred to) are preserved, often bearing a ring that served to hang them. The razor was an indispensable accessory for men: in fact, we can see from the frescoes that Etruscan fashion required men to present themselves with a well-shaven face (although images of men wearing beards, but well groomed and trimmed, are also frequent). The fashion of shaving one’s beard completely spread mainly as a result of contact with Greek civilization: in fact, young Greeks were not in the habit of wearing beards, and Etruscan peers soon began to imitate them. Another utensil that knows some diffusion in male trousseaus is the strigil, usually associated with sports practice (it was in fact used by athletes to remove oils from the body after competition or after training), but in Etruria it knew a more extensive use. It could in fact have been used to remove balms and ointments from the skin, or to remove depilatory creams (since, as Theopompus attests, both women and men shaved in Etruria), or even simply to cleanse sweat. The strigil, moreover, was also used in Etruria by women, who like men went to the gymnasium and thus needed to keep their bodies clean once they finished their exercises.

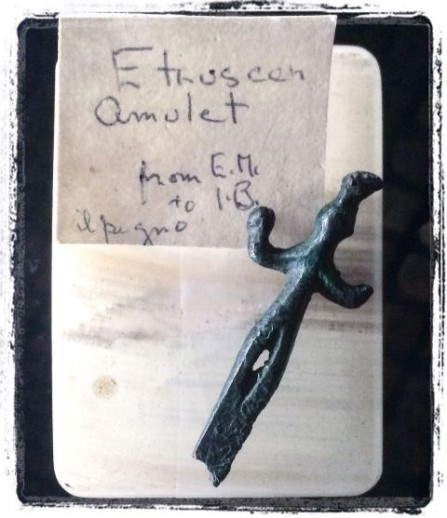

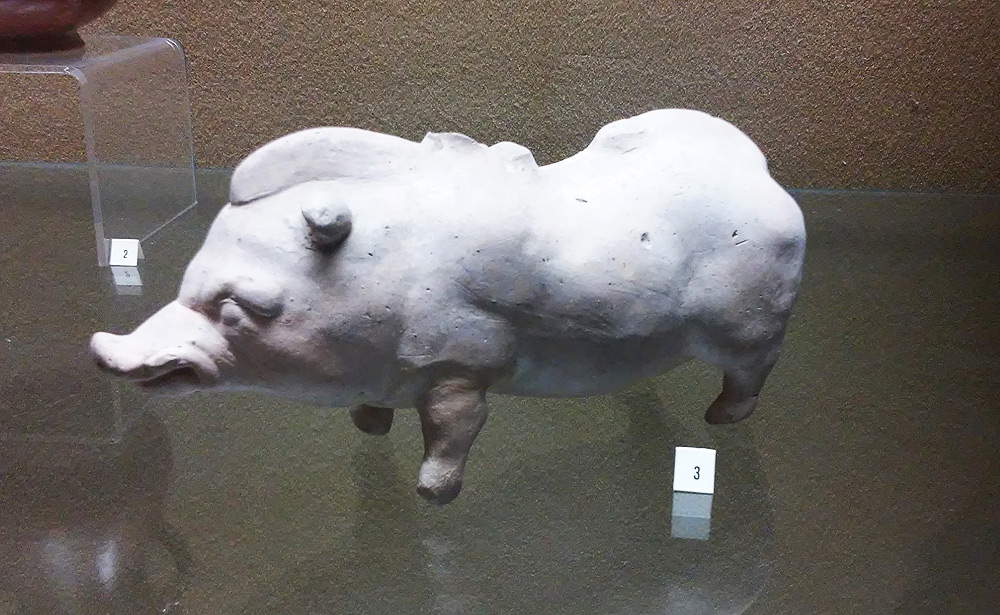

And speaking of women, the Etruscan female toilet set is well nourished. We know that Etruscan women used tweezers to pluck out unwanted hair, quite similar to those we use today. Particularly common then is the nail clipper, which could also take very elaborate forms: a very important nail-clearer, in the shape of a pendant depicting a nude female figure (perhaps a deity), is preserved at the Civic Archaeological Museum of Vetulonia, and its history is very interesting because it was purchased on the antiques market in Florence by the great poet Eugenio Montale who wanted to make a gift of it to his muse Irma Brandeis (the “Clytia” of his lyrics) as a pledge of love, and it came to the Vetulonia Museum last year, through a gift from the writer Marco Sonzogni, to whom the object had reached. Another accessory that could have become a small masterpiece of everyday use was the comb: a decidedly interesting example is the comb that is preserved at the Archaeological Museum of Maremma, made of ivory with relief and full-round decorations depicting fantastic animals (on the surface of the handle there are two sphinxes facing each other, while on the back we see two more beasts, probably two lions). Such elaborate decorations and the fact that it was made of ivory (a fragile material) suggests to us that, in fact, such a valuable comb was not really meant to be used every day and was, if anything, a display item. Then in the Etruscan lady’s beauty-case there was no shortage of balsam and unguentariums (also called, in the Greek term, aryballoi) that contained the perfumed oils that Etruscan women used in large quantities: all the imagination of artists was poured on these objects, since they have come down to us in the most disparate fashions. In addition to the normal globular-shaped balms, several in human or animal shapes can be seen in archaeological museums: for example, at the Archaeological Museum in Florence there are aryballoi in the shape of female busts, swans, hares, and fawns; at the Museum of the Territory of Bolsena there is a curious boar-shaped balsam bowl, and at the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome there is also one in the shape of a monkey.

A beauty-case was mentioned because the Etruscans (and this applied to both women and men) made use of a similar object, namely a container that was used to store toiletry accessories: this kind of trousse of antiquity was called a cista, was typically made of bronze, was cylindrical in shape, and was another object on which very elaborate decorations could be found (the handle of the lid, for example, consisted of sculptures depicting people or gods often caught in the act of hugging each other so as to bring them together to make it easier to hold). And the precious situla from Pania, one of the most important finds in the Archaeological Museum in Florence, was probably also a kind of beauty-case: it is a cylinder made of worked ivory, with a decoration featuring stories from theOdyssey. However, the accessory par excellence of Etruscan women’s toilette was the mirror: made of bronze, Etruscan mirrors consisted of a flat disk, formed in turn by a reflecting face (made of suitably polished bronze: there were no glass mirrors in Etruria) and a back engraved with scenes filled with figures, and a handle that could be cast in one piece with the disk or could be of different material (made of wood, bone or ivory). The Etruscans gave rise to a flourishing production of mirrors, which became one of the most typical objects of Etruscan craftsmanship. The scenes depicted on the back of the mirror were taken from the mythological repertoire (especially in ancient times, and they were, moreover, commented scenes with inscriptions, so Etruscan mirrors are also invaluable tools for learning about the language of this ancient people) or from everyday life (such as convivial scenes or erotic scenes). Some examples, among the best preserved: at the Archaeological Museum in Florence we find a combat scene with one of the characters identified by an inscription as “Aivas Telmuns,” or the Homeric hero Ajax Telamonius (this would therefore be a scene from theIliad, perhaps a duel against the Trojan Hector), at the Archaeological Museum in Bologna the so-called “patera cospiana” (as in the 17th century it was part of the collection of Marquis Ferdinando Cospi) is actually a mirror depicting the birth of Athena, while at the Guarnacci Museum in Volterra there is a mirror decorated with the figures of the Dioscuri.

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Lunate Razor with hunting scene (9th-8th century B.C.; iron; Grosseto, Museo Archeologico e d’Arte della Maremma). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Lunate razor (8th century B.C.; iron; Bolsena, Museo del Territorio). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Strigil (3rd-2nd century B.C.; iron; Cortona, Museo dellAccademia Etrusca di Cortona). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Depilatory tweezers (8th century B.C.; iron; Cortona, Museo dellAccademia Etrusca di Cortona). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Nettaunghie-pendant, with Eugenio Montale’s pledge (7th century B.C.; iron; Vetulonia, Museo Civico Archeologico “Isidoro Falchi”) |

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Comb from the Banditella Necropolis, Marsiliana d’Albegna (second quarter of 7th century B.C.; ivory, 9.5 x 11 cm; Grosseto, Museo Archeologico e d’Arte della Maremma) |

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Globular Balsamarium (590-550 BC; pottery, 6.2 x 6 cm; Maccagno, Museo Civico Parisi Valle) |

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Animal-shaped Balsamari (800-650 BC; pottery; Grosseto, Museo Archeologico e d’Arte della Maremma). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Swan-shaped Balsamari from the Flabelli tomb at Poggio della Porcareccia, Populonia (700-550 B.C.; pottery; Florence, Museo Archeologico). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Balsamari in the shape of hare and fawn from the tomb of the Flabelli at Poggio della Porcareccia, Populonia (700-550 B.C.; pottery; Florence, Museo Archeologico). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Balsamarium-shaped female bust from the tomb of the Flabelli at Poggio della Porcareccia, Populonia (700-550 B.C.; pottery; Florence, Museo Archeologico). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Monkey-shaped Balsamarium from the Maroi Tumulus at Banditaccia, Cerveteri (580-530 B.C.; pottery; Rome, Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Boar-shaped Balsamarium (3rd century B.C.; pottery; Bolsena, Museo del Territorio). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Etruscan art, Situla of Pania (third quarter of 7th century B.C.; ivory; Florence, Museo Archeologico). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Mirror with combat scene featuring an episode related to Ajax Telamonius (4th century B.C.; bronze; Florence, Museo Archeologico). Ph. Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan Manufacture, Mirror with Dioscuri confronted (5th century B.C.; bronze; Volterra, Museo Guarnacci). Ph. Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan manufacture, Mirror with scene of Minerva’s birth (second half of 4th century BC; bronze; Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico) |

Finally, to conclude: is it possible to hypothesize a typical makeup of the Etruscan woman? What were the products she used to fine-tune her makeup? Observing the painted scenes, both his wall and on ceramics, we can safely assert that Etruscan women liked light, sober and refined makeup, as can also be inferred from the frescoes of the Tomb of the Shields or from the same bust-shaped balsamarium mentioned earlier. Lipstick was used on the lips, the complexion of the cheeks was brightened with special products, the outline of the eyes was emphasized in black, and sometimes the eyes were brightened with an application of eye shadow: these were the essential, simple but elegant elements of Etruscanmakeup.

These were, in each case, products of plant origin. Lipstick was obtained from mulberry blackberries, anchusa roots (a plant similar to borage) or fig leaves. Eyeshadows, on the other hand, were made from crocus flowers, while the foundation of Etruscan women were clay slurries that were properly smeared on the cheeks, but red ochre could also be used. Etruscan women also used powder, which was obtained from the powder of far clusinum (Chiusi spelt). Then there was no shortage of perfumes, which were obtained from plants, flowers and fruits: bergamot, lavender, mint, almond and pine perfumes were prized. These were all essences that were mixed on a base of water and olive oil. Unfortunately, there are no written records left in the Etruscan language that have handed down more details to us: on Etruscan cosmetics we have no direct written sources. But we are sure of the fact that body care was a fundamental aspect of daily life for the Etruscans.

Reference bibliography

- Giovannangelo Camporeale, The Etruscans. History and Civilization, UTET, 2015 (fourth edition)

- Fabrizio Ludovico Porcaroli, Mater et Matrona: La donna nell’antico, exhibition catalog (Ladispoli, Centro di Arte e Cultura, from August 1 to November 1, 2014), Gangemi, 2014

- Agnes Carr Vaughan, The Etruscans, Dorset House Publishing, 1993

- Antonia Rallo (ed.), Women in Etruria, LErma di Bretschneider, 1989

- Massimo Pallottino, Rasenna: history and civilization of the Etruscans, Scheiwiller, 1986

- Arnaldo D’Aversa, The Etruscan Woman, Claudiana, 1985

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.