by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 08/09/2017

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

The theme of sleeping children is quite common in purist art: we see here examples by Giovanni Dupré, Tito Sarrocchi, and Lorenzo Bartolini.

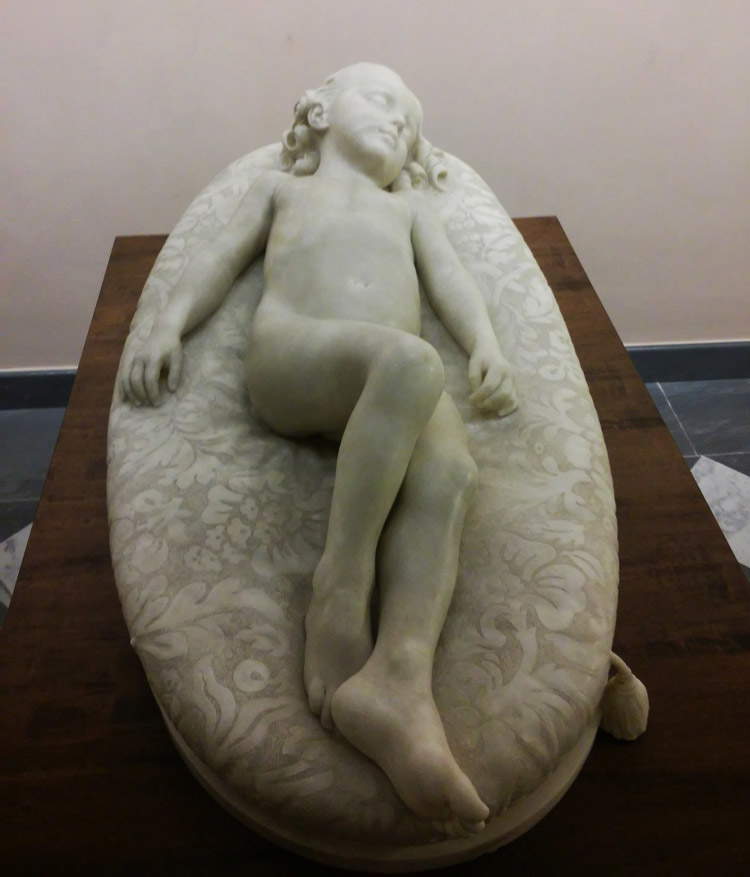

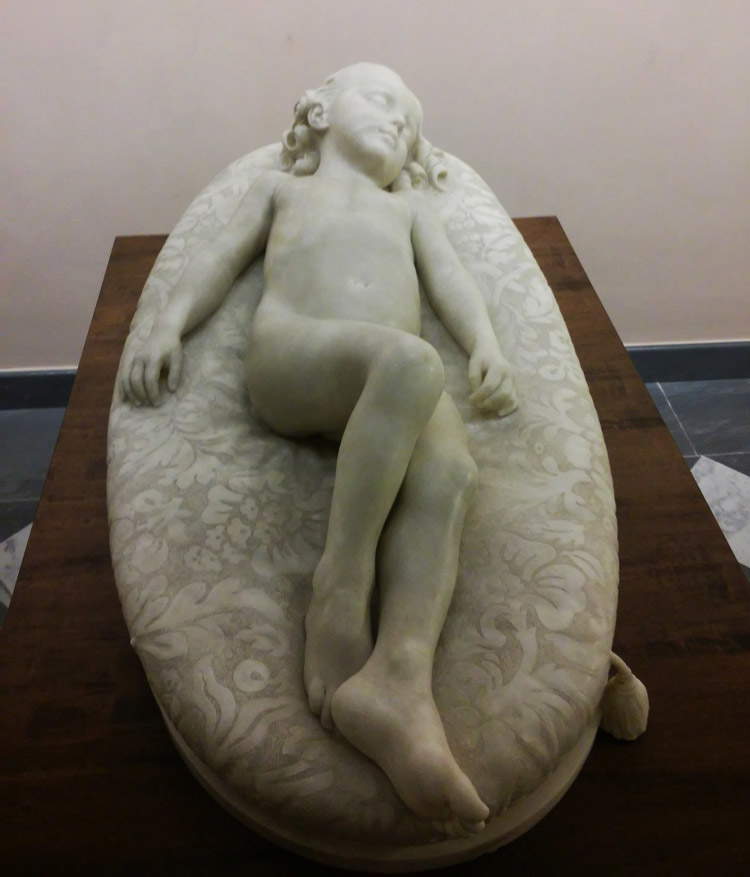

When Giovanni Dupré (Siena, 1817 - Florence, 1882) first exhibited his Sleep of Innocence, a marble sculpture he had begun working on in 1844, the success it garnered was considerable and unanimous. He presented it in public that it was not yet finished: in February 1845, in fact, he brought a plaster model to the exhibition of the Promotrice Fiorentina, the society that had the objective, common to many counterpart associations that arose in the mid-nineteenth century, of promoting (hence the name) the works of deserving contemporary artists. Dupré, at the time, was a talented young man, and with Sleep of Innocence he attracted all kinds of praise. Also grasping the novelty of his proposal were artists of earlier generations, beginning with Francesco Nenci (Anghiari, 1782 Siena, 1850), who, upon seeing the work, could not help but appreciate Dupré’s ability to imitate nature. This, after all, was the main goal of the artists belonging to Purism, a movement in the wake of which it is possible to include the art of Giovanni Dupré as well.

To get an idea of how contemporaries found it, it is possible to read Jean Duchesne’s exhaustive description of it in his mammoth Museum of Painting and Sculpture, a work intended to collect the best of Europe’s private and public galleries and which was published in some fifteen volumes between 1837 and 1845 (in Italy, it was the publisher Paolo Fumagalli who took on the task). In the book, the description accompanied a drawing that reproduced the plaster model of the work and was made by Étienne Achille Réveil, who was responsible for illustrating the works included in the Museum of Painting and Sculpture. In the text, Duchesne also regretted that the illustration did not do justice to the work: "in this our Museum we have already published several works by the young professor Dupré: now we give engraved this sleeping putto, which its author entitled the Sleep of Innocence, we regret, however, that we cannot give of it but the concept, since the admirable beauties of execution, for which the work we publish here excels, largely disappear in a small drawing, especially dealing with an attitude proper to see itself from top to bottom, as we see a baby in a cradle, and not already from the side. This putto does not already present an ideal, or a beauty of convention; but it is a true putto in the full extent of the word: everything is portrayed by nature with an accuracy and precision that is well difficult to surpass: you would swear you see a baby in a cradle."

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence (1846; marble, 60 x 110 cm; Siena, Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana). Ph. Credit Danae Project. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, front view. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, detail of the legs. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, detail of the hands. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, detail of the mattress. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, detail of the feet. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, detail of skin folds. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Giovanni Dupré, Sleep of Innocence, detail of the face. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

The commissioner of the work was a Sienese nobleman, Alessandro Bichi Ruspoli, who requested it from Giovanni Dupré, with whom he had become friends, in a letter dated September 29, 1844, now preserved in the archives of Villa Dupré in Fiesole. The work was challenging: we know of the existence of a model of different dimensions, reduced from those of the marble work now preserved at the Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana in Siena (it was donated to the Opera by one of Alessandro’s heirs, Laudomia Bichi Ruspoli, in 1953). It is therefore conceivable that the artist intended to make other replicas of the subject, smaller in size, but not only that: a plaster cast was in fact intended for theAcademy of Fine Arts in Perugia, since Bichi Ruspoli was a member of the academic college of the Umbrian institute. The marble was finished in 1846, and Dupré was personally responsible for transporting the work to Siena: the client intended to display it in the center of the living room of his home, within a circular sofa.

Invention and subject were not new, however. In fact, Dupré had looked to a counterpart work that Lorenzo Bartolini (Savignano di Prato, 1777-Florence, 1850), the leading sculptor of Purism, had made in 1823. The work is referred to in two handwritten correspondence as “statuina di un Innocenza figlia che perdette il sig.r Malchoff. Shipped to Moscow” and “small lying statue of the dead daughter of the Marchoff family in Moscow” (we have no more precise information about this Malkov family, or Markov, with whom Bartolini was in contact in 1823). Bartolini depicted her Innocence tenderly, in the guise of a little girl who does not appear to be deceased, but simply asleep, with her robe gently descending from her shoulders, revealing her arms and chest. Of the work we know only the plaster model, currently preserved in Prato at the local Museo Civico.

However, this was not the only Bartolinian work that inspired Dupré for his Sleep of Innocence: in fact, some motifs seem to be taken from the Table of Loves, a sculpture that Bartolini made in 1845 for the Russian prince Anatolij Demidov, one of the main patrons of the sculptor from Prato. Bartolini imagined his Table of Loves (also known as the Table of Genes) as a group composed of three figures, symbolizing love, vice and virtue. It is interesting to note the peculiarity of the subject of this work by Lorenzo Bartolini, who was inspired by the satires of Nicolas Boileau. The work was actually not traceable to precise passages from the French poet’s work, but reflected its general climate of condemnation of intellectual vice and exaltation of simplicity: as a result we can see how sensual vice, symbolized by the Bacchus who, drunk, falls into a deep and carefree sleep, is watched over by Divine Love (the angel holding him in his arms), while virtue (the putto clutching a compass in his hands), tormented by ambition and oppressed by fate, sleeps an agitated sleep. The ultimate goal was to illustrate, as we read in a note by the sculptor, life and reward “that has in the world the man from good.”

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Sleep of Innocence (1823; plaster, 49 x 105 x 40 cm; Prato, Museo Civico). Ph. Credit Polo Museale Fiorentino. |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Table of Loves (1845; marble, 163.5 x 130.2 x 126.4 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum). Ph. Credit The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Table of Loves, Detail of Divine Love and Sensual Vice. Ph. Credit The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

| Lorenzo Bartolini, Table of the Loves, Detail of Virtue. Ph. Credit The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

The differences between the work of Giovanni Dupré and those of Lorenzo Bartolini should be seen primarily in the Sienese sculptor’s greater adherence to the real: features that make his work particularly modern and to some extent anticipate realist sculpture because of that sense of close investigation of the natural datum that in purist artists is still subject to a degree of control, however. In Dupré’s work there is more than just a body so realistically caught in the abandonment of sleep and a face so delicately and tenderly described: examining the work closely, one can notice passages worthy of a great virtuoso, beginning with the damask decoration of the mattress on which the little girl sleeps, and continuing with the subtle and realistic folds of the skin (note, for example, those on the ankles), the points of light created by the spaces between one leg and the other, and the curls that lie on the bed. Scholar Ettore Spalletti writes in the catalog of the exhibition Dopo Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome (in Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, from July 8 to October 22, 2017), whose featured works include the Sleep of Innocence: “while Bartolini’s nudes obey a firm stylistic control of forms, Dupré’s appears abandoned in a sweet description of a tender modeling that lingers in details of great naturalness,” namely the details described above. These are “signs that hint at the now imminent overcoming of that puristic phase of his style that sees its culmination in the monument to Pius II for Siena.”

The Palazzo Cucchiari exhibition itself provided an opportunity for an initial and very interesting comparison between Dupré’s Sleep of Innocence and the Sleeping Putto by Tito Sarrocchi (Siena, 1824 Siena, 1900), who was Dupré’s pupil. Little is known about this sculpture: it was first mentioned in 1963, then art historian Piero Torriti indicated it, in his guide Tutta Siena contrada per contrada, among the works decorating the anticappella of Palazzo Sansedoni in Siena. On the occasion of the Carrarese exhibition, still Ettore Spalletti meanwhile suggested a possible year of execution for a work that remained of uncertain date, suggesting that it be assigned to a period close to 1874, at the same time as the realization of theSleeping Odalisque, given the closeness in the modeling of the forms of the two nude bodies, and then speculated that the commissioner was the same as Dupré’s Sleep of Innocence: in fact, the anticappella in Palazzo Sansedoni records the presence of a bust of Alessandro Bichi Ruspoli, sculpted by Sarrocchi himself, and a further bust (made, however, by Giovanni Dupré), that of Emilia Bichi Ruspoli, née Chigi, Alessandro’s wife. It would not seem unreasonable, therefore, to think that the Sleeping Putto was also commissioned by some member of the Bichi Ruspoli family, perhaps by Alessandro himself, who was a friend of Giovanni Dupré’s and had reached the age of sixty-seven in 1874.

|

|

| Tito Sarrocchi, Sleeping Putto (c. 1874; marble, length 80 cm; Siena, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena Collection). Ph. Credit Danae Project. |

|

| Tito Sarrocchi, Sleeping Putto, detail of the face. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Tito Sarrocchi, Sleeping Putto, detail of the face. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Tito Sarrocchi, Sleeping putto, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Tito Sarrocchi, Sleeping Putto, detail of hands. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

Sarrocchi decided to have his putto sleep on its side, lying on top of a damask mattress similar to Dupré’s and with its head resting on a virtuously outlined pillow: note the folds and seams on the sides. But the great naturalism of this sculpture goes beyond this and is especially evident in the expression of the putto, who in his sleep breathes with his mouth half-closed, through which we can glimpse the little teeth. The body, treated with a delicacy similar to that which distinguishes Giovanni Dupré’s Sleep of Innocence, appears to us delineated with the same softness, although perhaps more rigid than that of the master: nevertheless, the path that would shortly lead to the birth of realist sculpture is traced.

Reference bibliography

- Sergej Androsov, Massimo Bertozzi, Ettore Spalletti, After Canova. Paths of Sculpture in Florence and Rome, exhibition catalog (Carrara, Palazzo Cucchiari, July 8-October 22, 2017), Fondazione Giorgio Conti, 2017

- Fabio Gabbrielli, The Palazzo Sansedoni, Protagon Editori Toscani, 2005

- Ettore Spalletti, Giovanni Dupré, Electa, 2002

- Silvestra Bietoletti, Michele Dantini, L’Ottocento italiano: la storia, gli artisti, le opere, Giunti, 2002

- Marco Pierini (ed.), Tito Sarrocchi 1824-1900, exhibition catalog (Siena, Complesso Museale di Santa Maria della Scala August 7-October 3, 1999), Protagon, 1999

- Lucia Tonini, The Demidoffs in Florence and Tuscany, Olschki, 1996

- Carlo Sisi, Ettore Spalletti, Giuliano Catoni, La cultura artistica a Siena nell’Ottocento, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, 1994

- Piero Torriti, All of Siena contrada by contrada, Bonechi, 1988

- Sandra Pinto, Ettore Spalletti, Lorenzo Bartolini: exhibition of conservation activities, exhibition catalog (Prato, Palazzo Pretorio, February - May 1978), Centro Di, 1978

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.