Simonetta Vespucci: was she really Sandro Botticelli's muse and lover?

The “beautiful Simonetta,” the “sans par”: these were the two nicknames by which one of the most famous noblewomen of the Florentine Renaissance, Simonetta Vespucci, born Cattaneo (Genoa or Portovenere, 1453 - Florence, 1476), passed into legend. A woman reputed to be of unparalleled beauty, the object of desire of a great many men in mid-15th-century Florence, a member of one of the oldest Genoese families of nobility (the Cattaneos), married at only sixteen to the banker Marco Vespucci (a relative of the better-known Amerigo, the navigator who gave America its name), died very young (at only twenty-three, probably of the plague) and was accosted by the name of many artists of the time, for whom she would pose. Many have wanted to recognize her face, for example, in the Venus or the personification of the Primavera by Sandro Botticelli (Florence, 1445 - 1510), and there has even been a desire to attribute an emotional bond to the two, even on the basis of a legend (which is without foundation) that Botticelli asked to be buried next to Simonetta in the church of Ognissanti. The two were indeed buried inside the Florentine house of worship, but because the family tombs of both were in the same church (the Vespuccis held a chapel, while Botticelli was buried in the Ognissanti cemetery). What, then, is true about this story?

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Detail of the Birth of Venus (c. 1482-1485; tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Detail of Spring (c. 1482; tempera on panel, 207 x 319 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

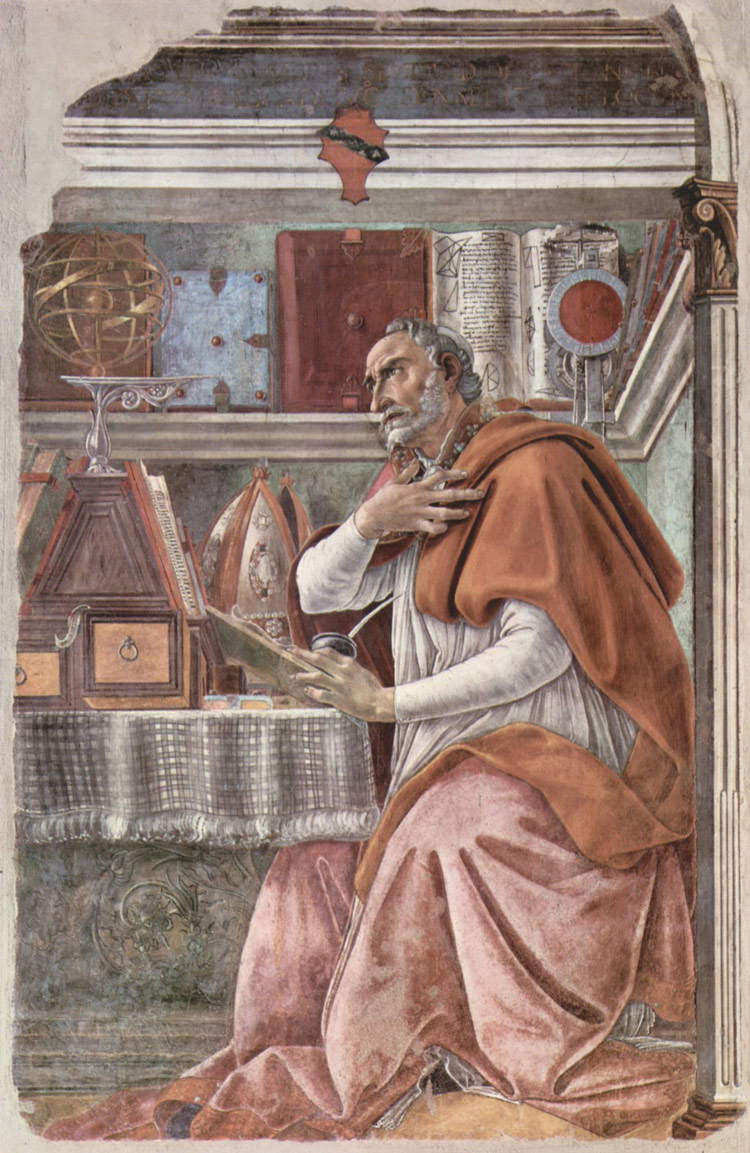

There is certainly some evidence to suggest that Sandro Botticelli and Simonetta Vespucci knew each other. In 1464 Sandro’s father, Mariano Filipepi (it will be useful to remember that Sandro Botticelli was actually named Alessandro Filipepi), had purchased a house on Via Nuova, adjacent to the Vespucci family’s dwellings, in the Borgo Ognissanti neighborhood. Sandro also later lived in this house, at least from 1470 until the end of his days. That there were good neighborly relations between the Filipepis and the Vespuccis is evidenced by the fact that the Vespuccis guaranteed a number of commissions to the painter, among them certainly the Saint Augustine in the studio of the church of Ognissanti (the Vespuccis, besides owning a chapel in the church, had also been among its main financiers). On Simonetta, however, there are very few documents. We know her date and probable place of birth from a document in the Florentine land register of 1469 (the year of her marriage), which lists her as having been born in Genoa (the fact that the village of Portovenere has recently been proposed as her birthplace is due to the fact that the Cattaneo family had estates in the La Spezia Gulf area, and to the fact that Simonetta’s name is not mentioned in the Genoese registers of the time) and sixteen years of age. At that time, therefore, she was already in Florence. However, no documents exist (or have not reached us) that could testify to a relationship between Sandro and Simonetta. How, then, would the myth of Simonetta Vespucci “Botticelli’s muse” have come about?

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Saint Augustine in the Study (c. 1480; detached fresco, 185 x 123 cm; Florence, Ognissanti) |

Following her death in 1476, Simonetta became the object of genuine veneration by the poets of Medici Florence, who saw in her a kind of personification of the concept of beauty. Lorenzo the Magnificent himself wrote four sonnets in her memory, the most famous of which reads: “O clear star that with your rays / Togli alle tue vicine stelle il lume, / Why do you shine so much more than your custom? / Why with Phoebus do you still contender? / Perchance and beautiful eyes, which has taken from us / Cruel death, who now too much presumes, / Welcomed thou hast in thee: adorned with their deity, / His fair chariot from Phoebus thou canst ask. / O this or new star that thou art, / That with new splendor adornest the heavens, / Call thou answer, deity, and our vows: / Lever of thy splendor so far away, / That to the eyes, which have of eternal weeping zeal, / Without offence happy thou show thyself.” In the notes to the sonnets, the Magnifico wrote that he received his inspiration after observing, one night, a very bright star in the sky: according to his poetic sensibility, that could be none other than the soul of the young woman (and this detail already gives us a clear image of the proportions that the myth of Simonetta had already reached). The poet Bernardo Pulci, in his lyric in tercets of endecasyllables In morte di Simonetta Cattaneo genovese, describes her as the “delight and zeal” of the realms of Venus, compares her to Petrarch’s “Laura bella” and Dante’s Beatrice, and greets her by immanginating her as a “nymph who on earth a cold stone cuopre / Benigna stella ora su nel ciel gradita.” And as a nymph, Angelo Poliziano also imagined her: the girl was in fact the protagonist of Pietro de’ Medici’s Stanze per la giostra del magnifico Giuliano, in which he fabled an idyllic (or, better said, platonic) love between Simonetta and Giuliano de’ Medici, the brother of the Magnifico killed in 1478 during the Pazzi conspiracy. Poliziano describes the appearance of the young woman in these terms: “Candida è ella, e candida la vesta / Ma pur di rose e fior dipinta e d’erba: / Lo inanellato crin dell’aurea testa / Scende in la fronte umilmente superba. / Ridegli attorno tutta la foresta, / E quanto può sue cure disacerba. / Nell’atto regalmente è regalmente mansueta; / E pur col ciglio le tempeste acqueta.”

From these descriptions to imagining her therefore the muse of artists, the step was very short. For example, the great Aby Warburg wanted to find in Poliziano’s poem the literary source that would inspire Botticelli in the creation of his two great masterpieces. It will be noted, in fact, how Poliziano’s description of the nymph fits well with Botticelli’s Primavera, and on this basis it was suggested that the female characters in many of Botticelli’s works could be identified with the Genoese beauty. In order to corroborate this hypothesis, some lines from Giorgio Vasari’s Life of Botticelli were brought up: in fact, the Aretine informs us that in the wardrobe of Duke Cosimo I, his contemporary, there were two “heads of females in profile,” “one of which is said to have been the inamorata of Giuliano de’ Medici.” This assertion by Vasari has therefore been interpreted (forcibly, one might say) to support the hypothesis that Botticelli had actually painted a portrait of Simonetta Vespucci (although Vasari does not specify better who this “inamorata” was), which has alternately been sought to be identified in the Portrait of a Lady in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, in that of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin or, again, in the Portrait of a Young Woman in the Palatine Gallery. All of these three paintings, in the past, were thought to be the portrait of Simonetta Vespucci: today, however, there is a tendency to rule out such hypotheses, and in an attempt to find an identity for the three young women many names have been proposed, without any satisfactory one ever being identified.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Ideal Portrait of a Lady (c. 1475-1480; tempera on panel, 81.8 x 54 cm; Frankfurt, Städel Museum) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Ideal Portrait of a Lady (c. 1475-1480; tempera on panel, 47.5 x 35 cm; Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1485; tempera on panel, 61 x 40 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina) |

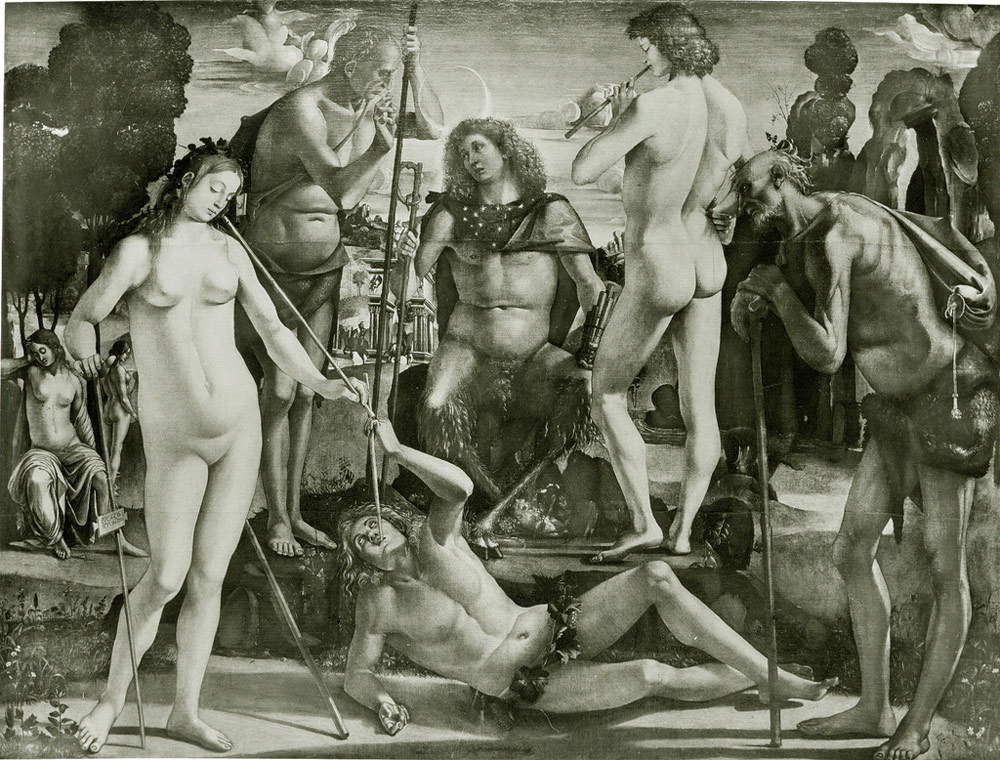

Then there are works by other artists in which Simonetta would be the protagonist: the most famous is probably the so-called Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Cleopatra, by Piero di Cosimo (Florence, 1462 - 1522) preserved at the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France. It should be noted, however, that when the girl disappeared, Piero di Cosimo was a teenager, just over 13 years old. This would thus be a posthumous portrait, which should therefore not be considered as a painting depicting the exact features of the young woman: it would be a kind of artistic homage, an idealized portrait intended to celebrate the woman with art, in the same way that poets celebrated her with words. If, for example, for Poliziano the young wife of Marco Vespucci was a nymph, for Piero di Cosimo she could have been a Cleopatra: let us also not forget that, for a woman of such high lineage as Simonetta, posing nude for a painter would have been considered extremely improper (and, moreover, posing for a painter was not too common a custom in the fifteenth century: it would become so only from the following century). Moreover, analyses conducted on Piero di Cosimo’s painting as early as 1970 showed how the inscription affixed to the base of the painting, and later used to justify the woman’s identification, actually dated to the late sixteenth century. And always decidedly shaky (not to say unfounded) would be the hypothesis that wants Simonetta to be the nymph who appears completely naked in Luca Signorelli’s lost Educazione di Pan, a 1490 painting that has also been read as a celebration of the polyamorous love affair between Giuliano de’ Medici and Simonetta.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, Simonetta Vespucci as Cleopatra (c. 1480; tempera on panel, 57 x 42 cm; Chantilly, Musée Condé) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Education of Pan (c. 1490; tempera on canvas, 194 x 257 cm; formerly in Berlin, Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, destroyed in 1945 in the fire at Flakturm Friedrichshain) |

What, then, is the truth? We are truly sorry to be unromantic, but the truth is that we know of no painting that has handed down to us the actual features of Simonetta Vespucci. Likewise, no document has ever been found capable of proving that Simonetta posed for Botticelli, or at least ever appeared in one of his works. More recent criticism has now debunked these hypotheses, believing them to be a reflection of a true “cult” for Simonetta Vespucci that spread in the 1570s and 1580s in Florence and that, in all evidence, also exerted considerable influence on nineteenth- and twentieth-century criticism. This, however, does not mean that portraits perhaps even truly resembling them did not exist at the time: in a letter sent by Simonetta’s father-in-law, Piero Vespucci, to Lucrezia Tornabuoni, mother of Lorenzo the Magnificent and Giuliano de’ Medici, reference is made to an image of Simonetta that would have been given to Giuliano after the girl’s disappearance. The fact that the portraits in Berlin and Frankfurt (we exclude the unattractive lady in the Palatina) have a rather high degree of idealization could lead to a lot of discussion as to whether one of them is that “image” mentioned by Piero Vespucci. But perhaps, as art historian Stefan Weppelmann recently wrote in a catalog entry on the Berlin portrait, “the question of whether the Berlin and Frankfurt paintings really represent Simonetta Vespucci seems far less relevant than their possible role as literary images and, consequently, their intent to depict the humanistic formulation of the ideal of beauty.” For in the end, looking at these works, we see nothing but ideal women conveying to us the canon of beauty of 15th-century Florence: and that is certainly no small thing!

Reference bibliography

- Keith Christiansen, Stefan Weppelmann, The Renaissance Portrait. From Donatello to Bellini, exhibition catalog (Berlin, Bode Museum, August 25-November 20, 2011; New York, Metropolitan Museum, December 21, 2011-March 18, 2012), The Metropolitan Museum, 2011

- Ross Brooke Ettle, The Venus Dilemma: notes on Botticelli and Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci in Notes in the History of Art, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer 2008), pp. 3-10

- Giovanna Lazzi, Simonetta Vespucci. The Birth of the Florentine Venus, Polistampa, 2007

- Davide Gasparotto, Anna Gigli (eds.), Botticelli’s tondo in Piacenza, Federico Motta Editore, 2006

- Rachele Farina, Simonetta. Una donna alla corte dei Medici, Bollati Boringhieri, 2001

- Anna Forlani Tempesti, Elena Capretti, Piero di Cosimo. Complete Catalogue, Octavo, 1996

- Ronald Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli. Life and work, Abbeville Press, 1989

- Umberto Baldini, Botticelli, Edizioni d’Arte Il Fiorino, 1988

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.