Simone Martini's Annunciation, a summit of the Sienese school.

On Jan. 10, 1799, Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi ’sAnnunciation left the small oratory of Sant’Ansano in Castelvecchio in Siena, also known as the church of the Prisons of Sant’Ansano, and departed for Florence, where it was to reach the Uffizi by order of Grand Duke Ferdinand III of Habsburg-Lorraine, who sent the Sienese in exchange two works by Luca Giordano recently acquired by the Uffizi, a Christ before Pilate and a Deposed Christ now housed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena. Art historian Enzo Carli, a great specialist in things Sienese, did not mince words in branding the will of the Lorraine: “it was [...] made to be plundered by the Grand Duke of Tuscany.” And since then it is at the Uffizi that the public can admire theAnnunciation, one of the pinnacles of the fourteenth-century Sienese school, a masterpiece about which pages and books have been written: Carli himself deserves the credit for having drawn attention to what is, to all intents and purposes, the oldest “critical reference” (so the scholar) known of theAnnunciation. It is a passage from the Volgarian Sermons of St. Bernardine of Siena, the sermons that the saint delivered in Siena’s Piazza del Campo in the summer of 1427, 45 days long distributed from August 15 of that year: “Have you seen that Annunciation that is in the cathedral at the altar of Saint Sano, next to the sacristy? For certain, that seems to me the most beautiful act, the most reverent and ’the most shameful that ever saw in Annunziata. See that she does not aim at the angel; even she stands with an almost fearful act. Ella knew well that he was an angel. What need was there for her to be troubled? What would she have done if she had been a man? Take it as an example, maiden, of what you must do yourself.”

Carli saw in the passage from St. Bernadine’s sermon a sort of ante litteram critical text since, in his opinion, the saint had “captured with admirable acuity that mixture of reverence, modesty and awe by which the Virgin is seized before the heavenly visitation and which constitutes a not secondary reason for the fascination that emanates from the martinian panel.” Of course, the art historian noted, St. Bernadine’s interpretation was conditioned by his religious sentiment (and also moral, since the reluctance of the Virgin to be admired in Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi’s masterpiece was taken as a paradigm for young women), but this sentiment must not have been so distant from the artist’s spirituality, just as it must have found wide acceptance among the Sienese, who, starting in 1333, would for several centuries be able to see the work on the altar of Sant’Ansano, the city’s patron saint, inside Siena Cathedral. Simone Martini (Siena, 1284 - Avignon, 1344) and his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi (Siena, 1380s - 1356) had painted the work specifically for the faithful who came to hear mass in the Sienese cathedral, and they also signed their names on the frame carved by Paolo di Camporegio and gilded by Lippo himself (the rest of the woodwork we see today, however, is 19th-century): “SYMON MARTINI ET LIPPVS MEMMI DE SENIS ME PINXERVNT ANNO DOMINI MCCCXXXIII.” We do not know, however, who was responsible for what, although on stylistic grounds it is possible to recognize Simone with the scene of the Annunciation, and Lippo with the roundels with the prophets (Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah and Daniel) and the two saints who appear in the side compartments, Ansanus and Margaret, both from Siena (Saint Ansanus is the patron saint of the Tuscan city). The work was later transferred in the late 17th century to the church of Sant’Ansano in Castelvecchio, where it is recorded in a 1741 inventory, which mentions it near the front door.

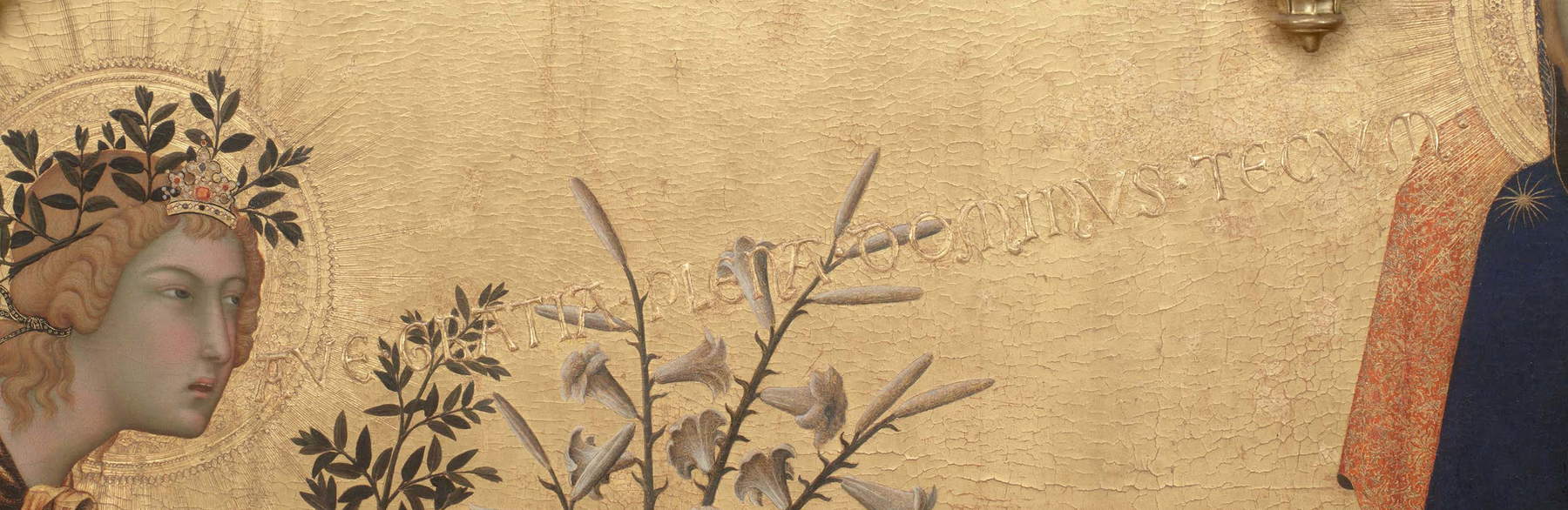

According to scholar Pietro Torriti, it is a futile exercise to question the portions to be attributed to different hands, essentially for one reason: “we are [...] in front of Simone Martini’s most celebrated masterpiece,” a reason for which “any more insistent attributive investigation seems sterile.” The overall direction of the painting, moreover, can only be ascribed to the flair of which Simone Martini had previously offered numerous proofs. Those who see this work for the first time (but the effect returns on subsequent viewings, even when one has become familiar with this painting) are impressed by the brilliance of the gold, which gives the scene a luminosity that is both mystical and precious. The whole background is gilded, and it is on the one hand embellished by the delicate punching of the haloes, with which Simone Martini has etched the gold laid on the panel with goldsmith’s skill, and on the other enhanced by the details also gilded in the brocade robes, the vase of lilies in the center of the scene, and also by the tablet with which the artist has highlighted the phrase that thearchangel Gabriel addresses to the Virgin Mary as a sign of greeting. We see it coming out of the angel’s open mouth, like a kind of 14th-century comic strip: “Ave gratia plena Dominus tecum,” or “Hail [Mary], full of grace, the Lord is with you.”

The scene takes place on a floor painted to imitate a colorful brecciated marble. The two figures are divided by the vase bearing tall lilies, a symbolic allusion to Mary’s purity and chastity. The archangel, dressed in a long white brocade tunic with gold embroidery and with a plaid mantle made of Scottish fabric (in the 14th century, cloth from those lands was already being imported to Siena) knotted around his neck, has just arrived and is kneeling in deference. His wings, minutely described and resembling those of a bird of prey, are still spread out, with their feathers pointing upward, while his cloak is still fluttering: his journey has therefore ended a few moments ago. Her blond hair is held down by a golden ribbon, she bears a diadem with precious gems and is girded with olive branches, the same plant she holds in her left hand and with which she is paying homage to Our Lady: it is symbolic of the peace God seals with humanity after original sin (Catholic doctrine in fact considers the Virgin conceived without original sin). The hands make a prissy, sophisticated, and acutely balanced gesture, moreover reflected in the almost identical position of the Virgin’s hands: one, the one holding the olive tree with extreme delicacy (with thumb, forefinger, and middle finger), is pointing downward, while the other, almost in perfect symmetry, is raised instead to point to heaven, as if to make it obvious who is responsible for sending the heavenly messenger. Mary sits on a pew decorated with elegant geometric patterns, covered with a cloth that is also brocaded. She recoils shyly, trying to close the blue mantle (the color symbolizes her divine dimension, as opposed to the red robe that alludes instead to the earth) with its border and sleeves highlighted with precious gold embroidery. On the right shoulder shines the star that is often seen depicted on the Virgin’s mantle, recalling the attribute of “Stella maris” (“star of the sea”) that was addressed to her, since, according to St. Bernard of Clairvaux, as for sailors so for the faithful the Virgin is the star that shows the course to follow. The star was also further a symbol of purity (stars were believed to be incorrupt and spotless heavenly bodies). And as is often the case in Annunciation scenes, Our Lady has just been interrupted in her reading: she is in fact still holding the sign with her finger (thumb, in this case) in the book. Her pose (she is caught in the act of retreating: a splendid Martinian invention that, as we shall see, will be widely successful) and her expression suggest a certain haughty severity but also a certain fear at the unexpected appearance of the heavenly messenger: he, on the other hand, looks at her with kinder eyes, as if to tell her that she has nothing to fear. Finally, above, we admire the dove of the Holy Spirit appearing in the sky in a golden disk, surrounded by eight cherubim.

Never before theAnnunciation by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi had Sienese art, the finest in Italy at the time, reached such levels of almost abstract sophistication, mystical elegance, transcendental suavity. The background, completely gilded, makes the scene appear almost like an apparition, in an abstract space, although the very solid vase, with flowers moving in all directions, contributes to the sense of depth (even more so than the throne executed with empirical perspective). “The Annunciation,” Marco Pierini has written, “marks a decisive turning point in the evolution of Simone Martini’s style in the direction of extreme formal abstraction, of an elegant and sinuous linearity, of a rethinking of the concept of space, no longer set up according to principles derived from Giotto, but as compressed on the surface and only barely suggested by the postures of the slender, immaterial figures of the angel and the Virgin and by the placement of the objects: the throne and the beautiful vase of lilies.” The angel’s arrival suggests balance and lightness, despite the contrast between the vertical mass of the wings and the squiggly fluttering of the mantle. The elongated proportions of the two figures suggest a sense of aristocratic distance. The edges of the robes, with their sinuous and irregular course, in their marked linearity describe unrealistic stride, folds that defy our perception, volutes that, like graceful arabesques, make the fabrics almost dance and render the bodies of the two protagonists impalpable, ethereal. The light is also enhanced by the unique technique of Simone Martini, who first spread gold leaf on the preparation, and then added color and left the gilding visible (those, for example, of the damask embroideries, or of the angel’s stole, or of his mantle), or worked in subtraction with the burin and chisel to perform the punching, thus giving relief to the surface. We also notice a certain dynamism: the angel appears to be in motion, at the end of his flight, while the Virgin is in a twist, and we almost seem to see her shielding herself, suddenly moving her arms to try to conceal her embarrassment at best. We should also note the contrast between the colors of the two figures: light tones for the angel, indicating his total belonging to the celestial sphere, against the midnight-blue mass of the Virgin, accounting for the earthly corporeality of her figure.

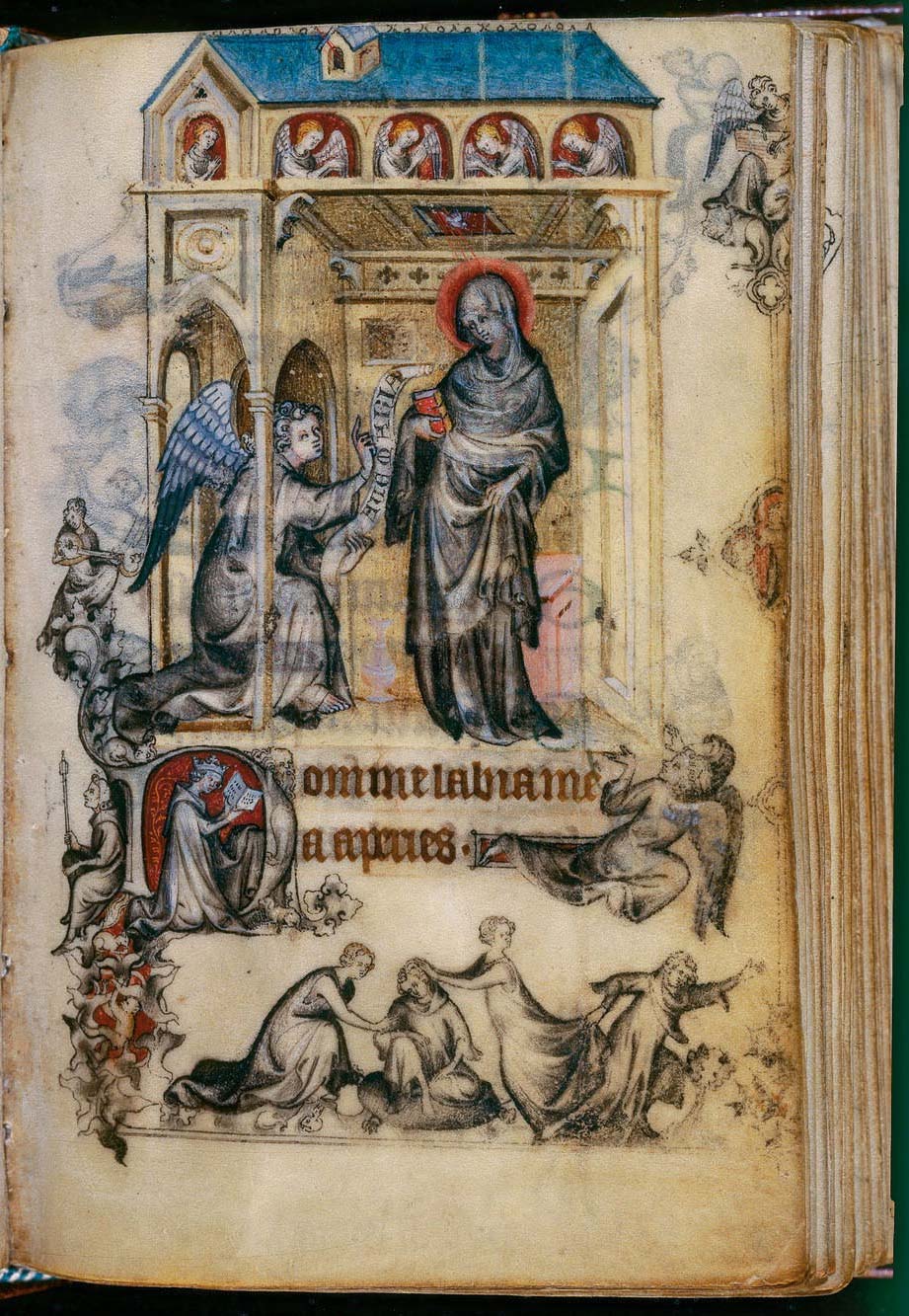

What are the assumptions behind this decisive turn in Simone Martini’s style? It is necessary to keep in mind that in early 14th-century Tuscany French Gothic had a considerable diffusion: panels, miniatures, masterpieces of goldsmithing had a certain impact especially in Siena where Simone Martini turned out, Max Seidel has written, to be “the artist who more than anyone else was intensely and variously confronted with these models,” manifesting a breadth of interests capable of ranging “from formal inventions under the sign of the legitimization of Angevin rule and the Sienese city-state, to the reproduction of the latest Parisian fashion in jewelry, to the replication of masterpieces of religious goldsmithing also used as models for the goldsmiths of Siena.” As an example, one could point to anAnnunciation by the French miniaturist Jean Pucelle (Paris, 1300 - 1355), taken from the Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, a rich illuminated codex preserved in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, as an example of the trends that inspired Simone Martini, while for elaborate goldsmithing one could instead call into question a cercle de tête preserved in the Louvre, similar to the diadem worn by the angel. Then there are details that could be rooted in precise iconographic precedents: the Madonna’s gesture of closing her mantle, for example, recalls that seen in a panel by Guido da Siena preserved at Princeton, while the hand holding the sign in the book recalls that of Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Annunciation in the panel now at the National Gallery in London.

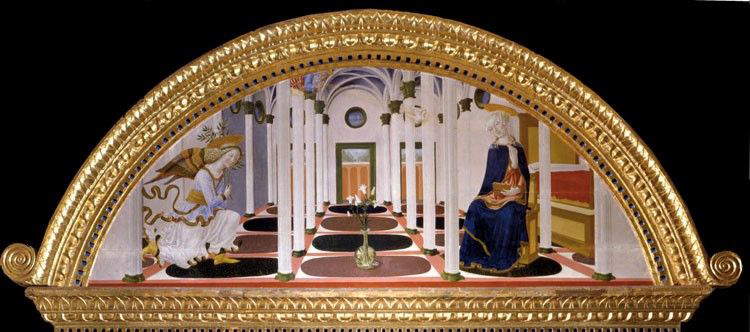

The Sienese painter, however, was not a passive remonstrator of other people’s ideas: it has been seen that the idea of the Madonna withdrawing out of timidity before the arrival of the angel is his invention. Not only that, it was an invention destined to have a centuries-long echo in Sienese art. Art historian Costanza Barbieri has subjected this invention to a rich and detailed analysis: the reluctance is motivated by both the sudden arrival of the angel and the chaste purity of the Virgin, but it also rests on doctrinal foundations “of which Simone’s iconographic invention is effective symbol,” Barbieri writes, “and as such perceived by the painters who deliberately wanted to be inspired by it in order to affirm not only a stylistic continuity, but also a spiritual one, within the broader panorama of the history of religious ideas and local devotion.” The image of the Virgin in hiding finds parallels in the sermons of the preachers of the time, who provided the faithful with clear images to divide the episode of the Annunciation into a number of distinct phases: the Franciscan, Roberto Caracciolo (Lecce, 1425 - 1495), namely, conturbatio (the disturbance at the arrival of the angel and listening to his words), cogitatio (the Virgin’s prudent reflection, a moment of intimate meditation before her response to the archangel),interrogatio (the question addressed by Mary to Gabriel) andhumiliatio (the moment when the Virgin declares herself willing to serve the divine plan). Even though Robert Caracciolo published his sermons in 1495, it was still a decoding of practices that had originated as early as the thirteenth century, and the iconographic theme of Mary’s reluctance finds its place in the religious sentiment of the time, even as a teachable moment, we have seen through the words of St. Bernadine, for the girls of the time.

These Mariological themes, Barbieri hypothesizes, probably had a certain diffusion in Siena where the ideology of the Franciscan Observants took root, “the most strenuous defenders of Marian privileges, which they divulged in impassioned sermons, in an intense preaching activity that spread throughout Europe between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries,” and of which Bernardino of Siena himself, one of their leading exponents, was vicar general in 1437. The fortune of Simone Martini’s invention could therefore be linked to the spread of these themes, as well as, of course, to the fascination he was able to exert on his generation and those that followed. Without calculating the almost identical replicas of Martini’s panel, the first to faithfully take up the master’s invention is Lippo Memmi himself, in theAnnunciation of the Cathedral of San Gimignano. We then find the same attitude of the Martinian Madonna in a masterpiece by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, theAnnunciation of the Hermitage of Montesiepi, where the Virgin is frightened to the point of clinging to a column, and then again in theAnnunciation painted by Andrea di Bartolo on the polyptych of the Pieve di Buonconvento in 1397, or in Taddeo di Bartolo’sAnnunciation of the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena. This pose then runs through the entire fifteenth century (one can see, for example, scenes by the Maestro dell’Osservanza and Vecchietta or that of theAnnunciation with Saints John the Baptist and Bernardine painted by Giovanni di Pietro and Matteo di Giovanni) until landing in the sixteenth century with theAnnunciation in the church of San Martino in Foro in Sarteano, painted by Domenico Beccafumi.

Other suggestions related to the time in which the painting was executed emerge from Simone Martini’s own stylistic turn. The mysticism of thisAnnunciation, according to the hypothesis formulated by Ferdinando Bologna at a conference on the artist held in 1988, holds the climate of the internal disputes within the Franciscan order that shook the Christian world in the 14th century, which saw the spirituals, who preached absolute poverty, facing off on one side for anyone who wished to follow the dictates of Christ and St. Francis, and on the other the community, who instead believed they should follow the rule approved by the pope (eventually the community would prevail, and Pope John XXII would recognize as heretical the idea that Christ and the apostles were not in possession of material goods). This was not simply a theological dispute, since the preaching of poverty risked undermining the foundations of the ecclesiastical hierarchies themselves (the pauperists, by advocating the renunciation of goods, also aspired to the separation of temporal and religious power: the Church would have to deal only with spiritual things). The mysticism of Simone Martini’sAnnunciation could thus be a reflection of the ideas of the time. But it is also a manifesto of beauty according to the Sienese painter, a definition of “spiritual beauty,” wrote Giulio Carlo Argan, “in contrast to the intellectual and moral beauty of Giotto,” and expressed through the purely graphic and pictorial medium. The artist “no longer seeks, as in the Majesty, the infinite possibilities of the relationship between line and color, but determines with clarity the type of the beautiful, and not only in the figures but in the objects, in the fabrics, in the branches and in the garlands of foliage and flowers. It is not a matter of poetized, idealized reality, but of a descent of absolute, or ideal, beauty until it is specified in the ’elected nature’ of things: ideal types arise precisely from that relationship of line and color. We admire the gracefulness of the Virgin’s motion of reluctance, but immediately notice that it is not given by the gesture, but by the sensitivity of the curved line of the mantle that separates the deep blue from the dazzling gold of the background. The Virgin (like Petrarch’s woman) is the highest ideal of the human person: she is enveloped in light, but does not emanate it. The angel is a celestial being of the same luminous and radiant substance as the golden background, the sky. The poetic sense of the painting is in that shy retreat of earthly color before the light that on all sides invests it.”

It is difficult to give an account of the pages that have been written on Simone Martini’sAnnunciation: many have tried to approach this supreme chapter of medieval art, to grasp its essence, sometimes even arriving at extreme interpretations, such as the decadent interpretation that Edmond and Jules de Goncourt gave in their Notes sur l’Italie of 1855-1856, where they even wrote that in the eyes of the two protagonists there is “something serpentine and strange.” Yet even readings so far removed from the true meaning of the work and the author’s true intent manage to give full insight into the importance of this work and the fortune it has encountered over the centuries to this day, to the point of being one of the most sought-after and admired works in the Uffizi.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.