Seventeenth-century Rome in the eyes of Gerrit van Honthorst: the painter's beginnings

Let us imagine a Dutch boy of just eighteen who had recently arrived in Rome. And let us imagine that this boy is none other than Gerrit van Honthorst: a young man who already had a good education, because in his homeland he had studied with Abraham Blomaert, one of the most important artists active in Utrecht, his hometown. So let us go back a few months, and imagine a discussion between the young van Honthorst and the experienced Bloemaert. The more experienced of the two had never been to Italy, but he was familiar with Italian Mannerist painting thanks to the prints and engravings that circulated in Flanders and Holland, and also thanks to the Dutch painters who kept up to date with the results of Italian art and then returned to their homeland. Let us imagine a conversation in which Bloemaert advises Gerrit to go to Italy: a complete painter with strong aspirations could not have become one of the greatest if he had not gone to study Italian art. And we imagine that young Gerrit heeded his master’s advice.

So we see him arrive, full of hope like all his peers who had and would have made the same journey, in early seventeenth-century Rome. We are not sure exactly when Gerrit arrived in Italy: perhaps around 1610. What did it mean for an 18-year-old Dutch boy to travel to early 17th-century Rome? It meant, essentially, everything. In Rome, a young man like Gerrit van Honthorst could walk among the remains of ancient Rome studying the vestiges that the greats of the classical age had left for posterity. Or, he could enter the sumptuous palaces to admire the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, Sebastiano del Piombo, and all those mannerist painters who had passed through Rome and in the Urbe had left their works. And let us not forget that the cardinals who roamed the palaces and churches of Rome came from all over Italy and all over Europe: so Rome was perhaps, to use a contemporary term, the most formidable marketplace of the time for artists, who could find countless patrons in the city. Provided they were good at it, of course!

Going to Rome therefore meant having direct and continuous contact both with a demanding, refined and wealthy patronage and with all the great artists of the past, more or less recent, as well as of the present. And in fact Gerrit van Honthorst was more interested in the art of the present than in that of the past, for he was immediately struck by the inspiration of Caravaggio, who had passed away precisely in 1610. Artists arriving in Rome could basically choose two paths: one was that of the academic and official art, represented by theAccademia di San Luca, founded a few years earlier by Federico Zuccari, and which at the time had in Cavalier d’Arpino its highest representative. The painters who opted for this path, which was more difficult but allowed them to enter better into the patrons’ good graces, would approach a solemn, weighty, often even pompous art that looked to the greats of the past. The second way was to approach the milieu of the naturalist painters: in essence, the Caravaggeschi, painters who saw in Caravaggio’s art an alternative to official art, a genuine way to tell the story of reality, and a way to bring the figures of religion (let us not forget that Rome was the capital of the Papal States) closer to the people. To really humanize them, in short. However, naturalists, as much as they could aspire to work much earlier than their colleagues who chose official paths (because they avoided the whole academic rigmarole of endless exercises and long gavettes), had more difficulty finding work, since not all patrons had yet accepted Caravaggio’s innovations. However, Gerrit van Honthorst immediately opted for this second path.

That the young Gerrit’s adherence to the Caravaggesque novelties was immediate is shown to us by a work recently assigned to van Honthorst’s catalog, the Prayer of Judith Before Beheading Holofernes, from the private Galerie Aaron in Paris. A painting with an unusual theme, because typically the biblical heroine Judith was depicted at the moment of killing her adversary, the Assyrian commander Holofernes who oppressed the Jews. And painting that shows us how typically Dutch elements, such as faces with strong features, draperies with heavily marked folds, and sudden transitions of light and shadow, are mixed with this new sensibility for light and naturalism. Could this then be Gerrit van Honthorst’s first work made in Italy? We do not know for sure, given also the documentary gaps on the painter’s biography, but the hypothesis could be plausible.

|

| Gerrit Van Honthorst, Prayer of Judith Before Beheading Holofernes, detail (ca. 1610; Paris, Galerie Aaron) |

The metamorphosis, the complete transition from a still Nordic Gerrit van Honthorst to a Caravaggesque and naturalistic Gherardo delle Notti, Italianized even in the name by which he would go down in history and by which he would be best known in our country, and due precisely to his penchant for nocturnal paintings, would occur with later works. For example, the Uffizi’s Supper with Spouses, a work from about 1614, which takes us into an atmosphere of merry banquets such as those might have been by Bartolomeo Manfredi, the Caravaggesque who perhaps more than any other represented the lightheartedness of the dinners, even simple ones, that took place in the taverns or homes of seventeenth-century Rome. However, van Honthorst, unlike many of his contemporaries, prefers an atmosphere of conviviality that moves away from the trivial and grotesque to which other artists, especially his countrymen, often stooped, in order to propose a delicate, composed and almost fine atmosphere, despite the fact that the physiognomies of the characters are as natural and truthful as ever.

|

| Gerrit Van Honthorst, Dinner with Spouses (ca. 1614; Florence, Uffizi) |

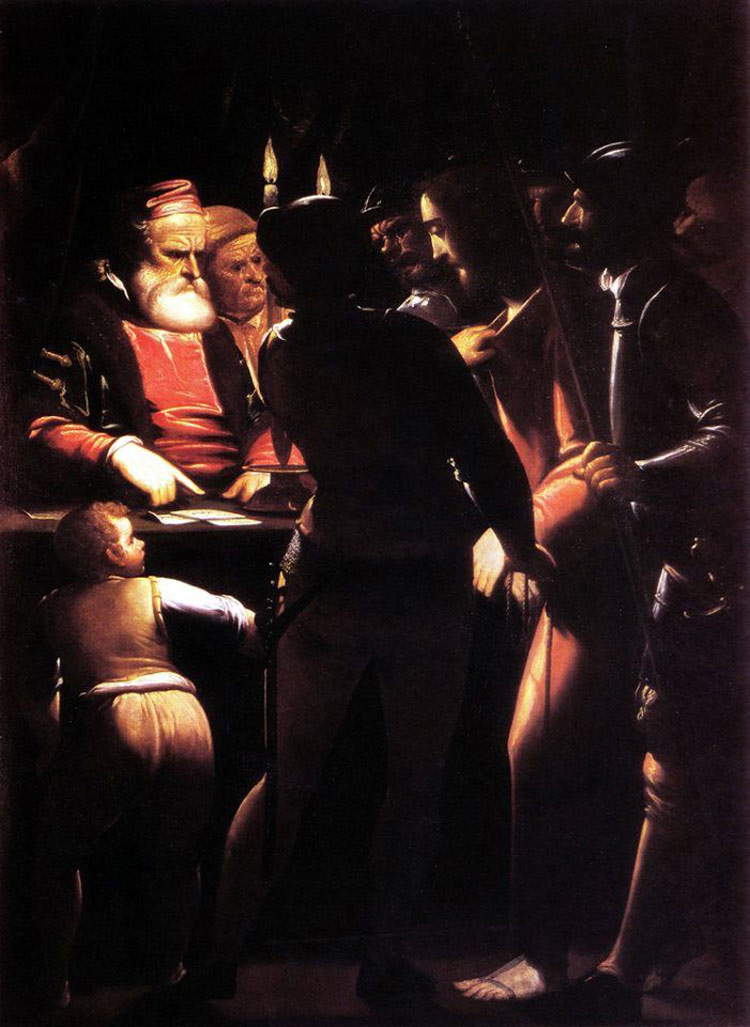

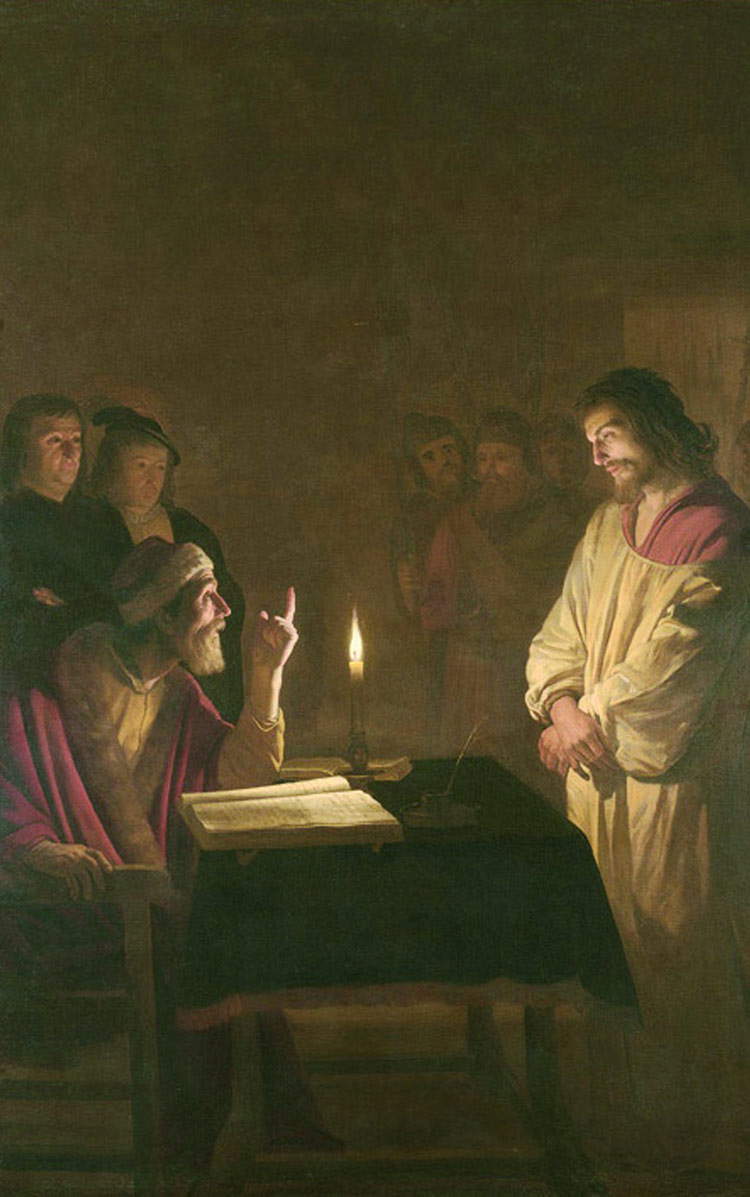

It happens that then, by dint of painting works that so captivate the viewer, you get noticed by an important patron, even if you decide not to take the official paths to glory. Gerrit thus entered the good graces of Vincenzo Giustiniani, a member of a prominent Genoese family with business in Rome, and the possessor of one of the most extensive art collections in Rome at the time. Giustiniani had already been a patron of Caravaggio, and given his appreciation for the Lombard’s art, he could hardly despise the art of van Honthorst, who excelled among the artists who were inspired by Caravaggio. Giustiniani not only had Gerrit work, but opened the doors of the collection to him: and this gave the young Dutchman an opportunity to come into contact with the art of one of the greats of the recent past, Luca Cambiaso, a very modern painter decades ahead of his contemporaries. Cambiaso was one of the first to set his works by candlelight, already more than twenty years before Gerrit himself was born. In the collections of Vincenzo Giustiniani, Gerrit had the opportunity to observe Christ before Caiaphas, now in the Museo dell’Accademia Ligustica in Genoa (incidentally, a museum that Genoese art lovers should visit at least once in their lives), but at the time in Rome in the palaces of Gerrit’s powerful patron. If, however, for Cambiaso the light was more “intellectual,” for van Honthorst the luminisms become more natural: and that Gerrit had Cambiaso well in mind and decided to revisit him in a seventeenth-century key, we notice from the Christ before Caiaphas in the National Gallery in London. We are around 1615: compared to Cambiaso, the outline characters recede, leaving the light to illuminate only the two protagonists, Christ and Caiaphas, whose features are up to date with Caravaggio’s achievements in terms of adherence to life.

And to think that, at the time this latter painting was made, Gerrit van Honthorst was only twenty-three years old. No wonder he would later become one of the greatest artists of the seventeenth century, but we could also say of all art history!

| Luca Cambiaso, Christ before Caiaphas (c. 1565-1570; Genoa, Museum of the Accademia Ligustica) |

| Gerrit Van Honthorst, Christ before Caiaphas (c. 1615-1616; London, National Gallery) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.