Savoldo incognito at Palazzo dei Diamanti

The recent exhibition on the sixteenth century in Ferrara curated by Vittorio Sgarbi and Michele Danieli brought back to attention once again the Madonna and Child in Glory, Musician Angels and Saints Paul, a Saint, Matthew, Catherine of Alexandria and Peter (fig. 1) from the da Varano chapel in the church of Santa Maria in Vado and kept since 1945 in the Archbishop’s Palace in Ferrara. The altarpiece presents a vertically bipartite composition: in the upper band, the Virgin holding her son is surrounded by an angelic concert lying in a semicircle above a cloud cover reminiscent of Raphael’s Madonna di Foligno and the Madonna and Child in Glory and Angels of theOrtolano conserved in Bologna; in the lower band, a not dissimilar symmetrical arrangement involves the five saints - in the foreground Paul, Matthew and Peter, between whose shoulders the faces of the two women emerge, in uncovered analogy with theEcstasy of Saint Cecilia (fig. 2) - facing the divine apparition, with the exception of the unknown saint intent on staring directly at the concerning.

The canvas is exhibited and listed as a work “already attributed to Giovanni Luteri known as Dosso” and executed between 1515 and 1519, but in the catalog text it is retained among the master’s works1. This contradiction demonstrates all the enduring difficulty of taking a position with respect to the attribution formulated in 1981 by Carlo Volpe2 taking up a late eighteenth-century notation by Cesare Cittadella who identified the altarpiece as one of Luteri’s earliest works. To tell the truth, the recognition, later shared by Sgarbi3, was the goal of a path made tortuous by the stylistic discrepancies detected with respect to works of more certain Dossesque authorship, in light of which the local literature had already derubricated the canvas as a school work, and Amalia Mezzetti had omitted it from her reconnaissance4; even Alessandro Ballarin5, in attempting to make the Varano altarpiece the fundamental junction of passage between the youthful group brought together by Longhi and the works of his maturity, would move over rough ground. Following the reconsideration of Luteri’s formative years made on the occasion of the Ferrara, New York and Los Angeles exhibition and culminating on the one hand in the anticipation to 1513 of the beginning of the execution of the central altarpiece of the Costabili Polyptych with Garofalo, and on the other in theother in the expulsion from the catalog of a large part of the Longhi group, the asperities encountered by previous studies of the altarpiece would later induce Mauro Lucco6 to deprecate its attribution to Dosso in favor of an “anonymous Po valley”. In this context, the comparison with the Madonna di San Sebastiano (fig. 3) by Luteri proposed by the recent exhibition definitively confirms how the profound linguistic dissimilarities that separate them make the attribution to the same author of the altarpiece from Santa Maria in Vado untenable.

The most striking element that distances the Varano Altarpiece from the one executed by Luteri for Modena cathedral is the almost total absence of landscape, on which the artist exercised his bold luministic and meteorological research in the footsteps of Giorgione and Titian, giving voice to a fiery lyricism. In the Ferrara Madonna and Child with Saints there is, indeed, a complete inversion of that relationship of domination and absorption of the figure by nature that distinguishes Luteri’s early small-format production, witnessed in the exhibition by such significant works as the Zingarella di Parma and the Viaggiatori nel bosco di Besançon, and which then finds an equal balance precisely in the mature Madonna di San Sebastiano. In the canvas from Santa Maria in Vado, the thronged bodies of the saints instead erect a massive screen wall of the village that can barely be glimpsed at their sides, echoing the lower band of Raphael’s St. Cecilia with a fidelity that is not to be found-what which had not avoided surprising Volpe himself-not even in a Dossesque work marked by a fascination with the Madonna of Foligno and the Vatican Rooms such as the Uffizi’sApparition of the Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Evangelist from Codigoro. It is worth noting, in this regard, how a bipartite setting similar to that of the altarpiece also animates the sketch of a Coronation of the Virgin that appeared on the back of the canvas and was entrusted to a difficult-to-read reproduction.7 The upper band is inspired by Florentine models-Beato Angelico, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio-while the sculptural pose of the saint that stands out in the center of the lower one in the same position as the St. Matthew is modeled on theArgo frescoed by Bramantino in the Castello Sforzesco; all references most likely out of the reach of the young Dosso.

If the Varano and San Sebastiano altarpieces seem to be united by a similar quest for monumentality in the layout and volumetric rendering of the figures, on the other hand, on closer inspection the latter are described quite differently: exalted in their athletic and classically proportioned limbs, emphasized all the more by their heroic poses, the half-naked ones in the Modenese altarpiece; far more compassed and weeklike are the three saints in the foreground in the Ferrara altarpiece, whose steadfastness, already noted by Volpe, seems to be founded first on the generosity of the draperies than on the intrinsic power of the bodies wrapped in them, which are, moreover, oversized compared to the small faces. A further, decisive factor of differentiation coincides precisely with one of the most distinctive features of Dosso’s personality, namely the chromatic direction: the scorching, sulfurous tones of the Modenese altarpiece are diluted in the more habitable, if pierced by sudden flashes of frost, tones of the Ferrara altarpiece - see the humble shirt of an acid green sprinkled with light worn by St. Paul, placed in a contrast alien to all tonalism with the earthy orange of Lucia’s and Pietro’s cloaks. In this respect, the Santa Maria in Vado altarpiece, in which the same hues reappear between figures, appears marked by a greater parsimony of means than the opulence of the San Sebastiano altarpiece, which flaunts the potential of Venetian color lit by an inner flame. In the Ferrara altarpiece, conversely, a luministic sensibility is at work, if possible even more subtle than Dosso’s already acute one, as revealed by the shadow that cuts cleanly, for no apparent reason, across Matthew’s face to spread more softly over the wrinkled forehead, mouth and cheeks of the elderly Peter. There is very little Venetian but much Flemish in this investigative use of lateral light and just as much Lombard, or rather more precisely Milanese, in the pressing dialogue between light and shadow.

If the Varano Altarpiece cannot be included in Dosso’s catalog, the comparison proposed in the exhibition with the later Apparition of the Madonna and Child to Saints John the Evangelist and John the Baptist in the presence of Ludovico Arrivieri and Calzolaretto’s wife (1522), to whom the canvas was attributed by Giuliano Frabetti, is only worth relativizing the commonality of the “chromatic facies” and the “tight compositional layout without any scenic artifice ”8 -in truth applied more rigorously in the Santa Maria in Vado altarpiece and more likely suggested to Cappellini by the Codigoro altarpiece.

In order to investigate the authorship of the painting under consideration, it seems appropriate, at this point, to resume the paths turned toward directions other than Ferrara already sketched out and immediately interrupted in an attempt to ensure - amidst aporias of a chronological nature as well, as if the Brescian painting of the 1920s could explain the Ferrara painting of the previous decade - a convergence with the still mostly obscure path beaten by the young Dosso. It was Volpe himself, in fact, on the trail of Longhi, who had suggested a “mental friendship between the Ferrarese and the Brescian Moretto” marked by a “common and heartfelt devotional, antiquarian, and sincere inclination ”9 that embraced with it even the early “Savoldo ’of the hermits’”10; Ballarin followed these indications by recording in the Pala da Varano Luteri’s encounter with “the originality of a Po Valley culture as other than that of the lagoon ”11. Conversely, the canvas had been exhibited at the 1990 exhibition on Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo as a “stimulating precedent ”12 for the sacred works of the Brescian painter, while maintaining the attribution to Dosso. For Lucco, finally, the anonymous Po valley author of the canvas had “knowledge ranging from Ferrara, to Mantua, to Cremona, and little or nothing having in his background Giorgionesco and Titianesque ”13, characteristics that distanced him from the head of the “Longhi group”, identified in Sebastiano Filippi da Lendinara; the scholar also recognized the same hand in anAscension of Christ with the Twelve Apostles on panel, then in a private collection and later acquired in 2005 by the Fondazione Carife for the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara (fig. 4), suggesting en passant a significant juxtaposition with a Head of a Man from the Musée de Beaux-Arts in Dijon attributed to Savoldo.

The two paintings on display at the Palazzo dei Diamanti are indeed united by a bipartite composition in two horizontal bands, which in the panel places the celestial rarefaction of the angels surrounding the Risen Christ in contrast to the crowding of the disciples, constructively akin to that of the altarpiecealtarpiece but expressively more animated, in direct reaction to the excited handling of the onlookers in Titian’sAssumption, and close in rhythm and arrangement to Rosso’sAssumption in the Chiostrino dei Voti commissioned in 1513. But the panel’s disciples appear as much more rustic and firmly planted in Lombard soil than their lagoon and Florentine counterparts as the five saints in the Pala da Varano seem like figurants caught in staging Raphaelesque Ecstasy at a village fair. In theAscension, on the other hand, the quest for grandeur that underlies the Arcivescovado altarpiece seems to slumber because of the reduced format of the panel and the smaller size that the figures take on in relation to the space - a possible sign of a greater distance from the first impact with the Santa Cecilia and an influence of Mazzolino - freeing on the left margin a glimmer sufficient for a patch of landscape to open up. This is invested by a dazzling light that melts the forms in a way more akin to the crumbling of the ruins in the background of Altobello’s former portrait of Cesare Borgia than to the fireworks triggered in the fog by Dosso.

Rather than reiterate digressions already undertaken without outlets or trace Dosso’s encounter with Savoldo back to the moment of the Pala da Varano, the double confrontation staged at Palazzo dei Diamanti induces us to break the hesitations and propose an’explicit attribution of the two paintings to the Brescian painter; comforted in this by the relations with the Este court made known by Vincenzo Farinella in 2008 with the publication of a payment received by Savoldo on February 2, 1515 for having sold three unspecified figures to Alfonso I14.

Indeed, it is possible to discern in the two Ferrara works, even more clearly than in the group of works collected before the 1521 San Nicolò Altarpiece, some significant anticipations of Savoldo’s mature works. At the compositional level, the “grandiose spatial setting ”15 of the Pala di San Domenico di Pesaro (fig. 5) preserved in Brera can be read precisely as a simplification of the layout of the Pala da Varano, where the elimination of the central figure and the symmetrical fifths arrangement of the four saints opens the view to the famous sea view, a perturbation destined to close again soon in the Pala per Santa Maria in Organo. Savoldo’s choice of a composition divided into an earthly and a celestial level, opposed by Savoldo to the indications of the Dominican patrons still bound to the formula of the Madonna enthroned surrounded by saints, may thus reveal, in addition to a reaction to the Gozzi Altarpiece made by Titian in 1520 for the Ancona church of San Francesco, a desire to take up and evolve the proven Ferrara model. The license requested and obtained to add to the “uno angelo che soni uno violone,” perhaps provided for in the contract at the foot of the throne as in the San Nicolò Altarpiece, a second musician angel that projects the profile of the right-hand angel of the Ferrarese canvas by three-quarters, replicating the upward foreshortening of the head, which is in both cases slightly undersized in relation to the body, seems to point in this direction. Such a Morellian trait moreover distinguishes the same musician angel of the San Nicolò Altarpiece, which - it should be recalled - in all probability represents Savoldo’s only autonomous invention within the composition prepared by Pensaben. In the lower band of the Pesaro altarpiece, moreover, Peter and Jerome are posed in poses almost superimposed on those of Peter and Paul in the Varano Altarpiece, and they also share with these the overabundant draperies with consonant chromatic tones.

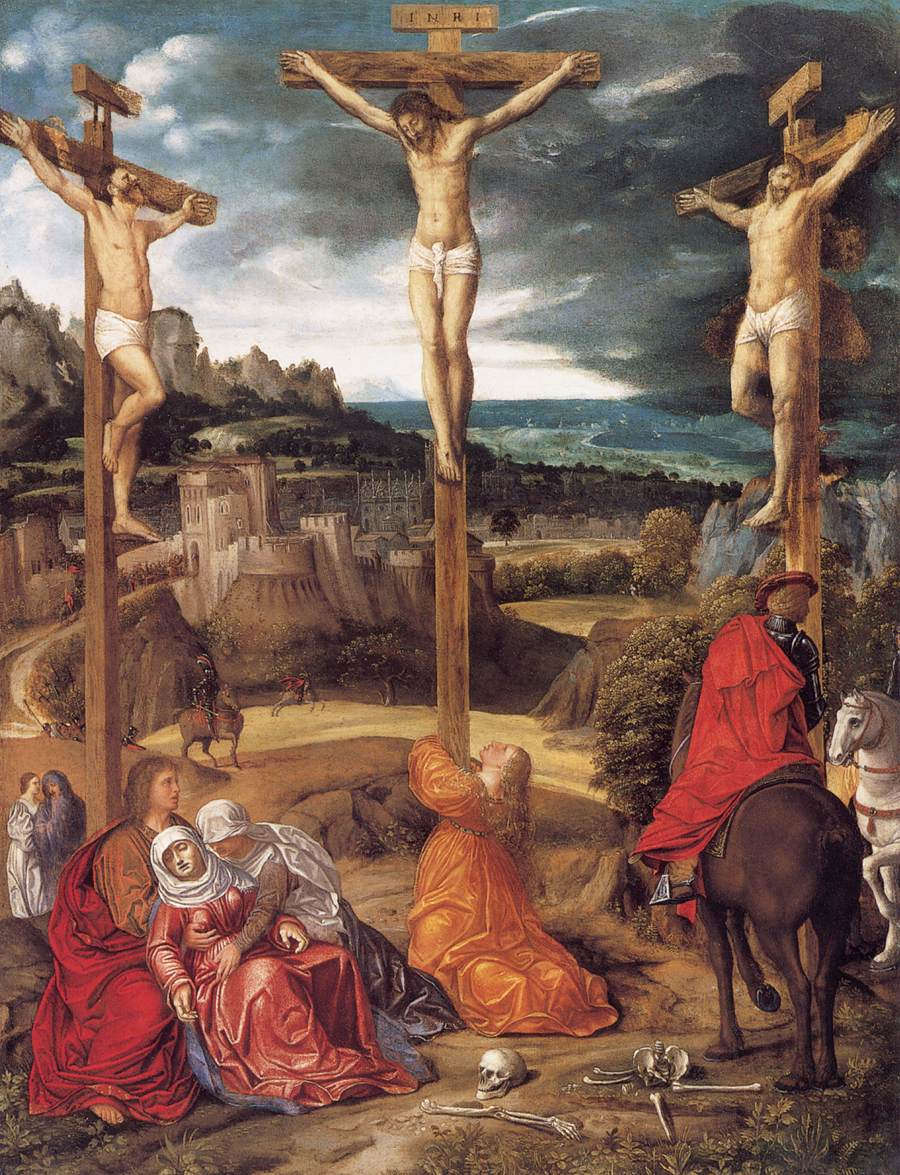

In addition to the Ferrara altarpiece itself, a compositional touchstone for theAscension can be found in the Crucifixion formerly in Monte Carlo, now in the Alana collection in Newark attributed to Savoldo by Mina Gregori with a date in the first half of the second decade16 (fig. 6), which appears to be united with the panel by the smaller size of the figures relative to the pictorial surface, the heartfelt but measured participation in the event by the bystanders, and the similar meteorological sensibility-more Lombard than Ferrarese or Venetian-that is made concrete in the stormy thickening of the clouds on the right. On the other hand, the more elongated character modules than in the Varano Altarpiece, though related by the similarly small heads, may represent an echo of Brescian examples at the dawn of the second decade such as Romanino’s debut pieces between the Compianto dell’Accademia and the Polittico del Corpo di Cristo.

Another eloquent element supporting Savoldo’s authorship of the two works under consideration consists in the close resemblance that can be detected between the physiognomies of the characters: the St. Peter of the altarpiece very close to the Nicodemus of the Kunsthistorisches Compianto (fig. 7) and to the Saint Anthony the Hermit of the Gallerie dell’Accademia and similarly sculpted “by intense light” allowing “admirable optical acuity in the rendering of the epidermis and the abundant dogia. ”17 the Virgin with the small mouth, long straight nose and dreamy gaze like the Marys of the Pesaro Altarpiece and of so many Adorations of the Shepherds; the St. Matthew almost twin to the Christ of the Lamentation and intent on assaying space with his right hand foreshortened “Flemish-style” like the Philosopher (fig. 8) signed from the same museum; the elderly disciple with the white frayed beard on the right margin of theAscension consanguineous with Pesaro’s St. Jerome and caught in the same upward foreshortening; the two young apostles with thick tousled hair portrayed from behind almost as studies for the same Viennese Philosopher.

The same luministic sensibility unmistakably Lombard that enhances the faces of the Ferrara saints and disciples, touching truly Precaravaggesque - or postcaravaggesque, as Testori suggested - achievements in the St. Peter of the Archbishopric, in the apostle on the far right of theAscension portrayed against the light à la Bramantino and in the foreshortened hand in penumbra of the apostle on the far left, anticipates the exploits touched by the Brescian in the galleries of faces shrouded in darkness that populate the Lamentation in Vienna, the Tobiolo of the Borghese Gallery, theAdoration of the Shepherds in Turin and the Ambrosian Transfiguration. Nor can the light-silvered loincloth of the Risen One prelude anything other than the snow-white robe of the Christ blazing on the Milanese painting or the equally supernatural robe of theAnnouncing Angel of Pordenone, while the icy silver gleams lit on the mantle of the altarpiece’s Paul already hint at the opal sheens of the Magdalene’s robes, which find a common precedent in the robe of the right-hand magician of Bramantino’s LondonAdoration (1495-1500).

The attribution can finally do justice, more than the Accademia Galleries’ Saints Paul and Anthony Hermits from the Manfrin collection can (fig. 9), to Savoldo’s Ferrara frequentations. The 1515 payment anticipates by a little, in fact, the probable temporal placement of the Varano Altarpiece, which we would like to imagine as Volpe did executed in direct take on theEcstasy of Saint Cecilia, by 1516. Nor is the failure to find in the ducal archives further references to the painter, with which Francesco Frangi18 asserted the episodic nature of the relationship with Alfonso, worth excluding his more assiduous presence in the Este city, finding us dealing quite clearly with private commissions. On the other hand, Mina Gregori, dealing with the early Crucifixion, glimpsed in it the signs of a passage to Ferrara as a detour from the road between Parma and Florence, where Savoldo is documented in 1506 and 1508 respectively, and Mantua, for which, according to the scholar, the panel was executed. The very presence in theCoronation of the Virgin sketched on the back of Florentine references dating from the late 15th century may help account for a frequentation of the Medici city in the early part of the following century.

In this context, the Ferrara altarpiece, with its search for monumentality stimulated by the large format and the examples of Raphael and Fra Bartolomeo, which already anticipates the altarpieces of the maturity, seems to follow absolute firsts of markedly northern accent-the Parisian painting itself, theApostle of Besançon, theElijah fed by the Raven of Washington, the Temptations of St. Anthony of San Diego and the two Hermits. TheAscension, to be placed close to 1518 because of the update on the Frari altarpiece, seems instead to mark the watershed beyond which the lagoon influence begins to penetrate the Po Valley hinterland in which the Brescian had grown up, substantially concomitant with the Torments of St. Jerome in the Museo Puškin, already alerted to theIncendio di Borgo that Savoldo would have been familiar with thanks to the cartoon sent as a gift to Alfonso I in late 1517 and touched by an incipient Titianism.

As for the compositional differences between the two works related to the disparity in format, rather than helping to reconstruct a linear stylistic development, rarely manifest in Savoldo’s career, they allow us to appreciate the diversity of inspiration and ambition that always distinguishes his “far piccolo,” quantitatively prevalent in the catalog, from the few examples of “far grande” coinciding with the altarpieces. Similarly, the marginal role to which the village is relegated in both, the main element of discrepancy between the Ferrara paintings and the other early works, can be read as both a necessary silence so that the lenticular Flemish vision could re-emerge in the 1920s imbued with a’air by then fully Venetian, and also of an anticipation of the sentiment detected by Ballarin in the mature works of a fundamental alienation of man from nature, which even in the apparently panic visions of the Resting from the Flight into Egypt remains a mute backdrop impenetrable to human inquiry19 - of which, at the limit, one can even do without.

Taking up in conclusion and in a different light the relationship of the two paintings with Dosso, thanks to these it seems possible to untangle in part the web of relationships and the nature of the tangencies already noted between the Este painter and Savoldo. After the reassignment of part of the works attributed to the young Luteri has led to a re-dimensioning of the Po Valley moods that had been identified in them, it seems more appropriate to trace back precisely to the encounter with the Brescian some experiments in “verismo” lombard implemented later by Dosso, such as the cut on the face of the Saint John the Evangelist of Codigoro and the rustic masses rough-hewn by the light of the Sapienti,20 and by Calzolaretto, such as the face scrutinized by the shadows of Saint Peter in Saint Francis Receives the Stigmata with Saint Peter, Saint James the Greater, Saint Louis of France and a Franciscan. The Varano Altarpiece, together with the collaboration with Garofalo, may also have strengthened Luther’s interest in Roman novelties that would find expression a few years later, while the impact with the original interpretation of Giorgionism elaborated by Dosso may have prompted the Brescian to embark on (or resume?) the path toward the wider horizons of the lagoon, where he would have remembered Ferrara by giving life to the “auroras with reflections of the sun” dear to Paolo Pino.

What, in any case, the two paintings discussed confirm, not without arousing a motion of astonishment by which all the hesitation that has so far prevented their inclusion in his catalog is explained, is Savoldo’s ability in his still elusive youth to react to each of the encounters he made - with Raphael, with Titian, with Dosso himself - and to make them his own, revisiting them and extracting them from memory in order to change, from time to time, his skin without, however, affecting, as Testori would still say, the deep substratum of the subject. The certainty is that not even the addition of these two pieces is enough to illuminate the human, before than artistic, mystery of the Brescian, nor to trace more modestly the line of the give-and-take matches with Ferrara. The hope is to stimulate new agnifications and new reevaluations that will finally allow the last piece of the puzzle, that of the common Friulian friend, to be embedded as well.

Notes

1 MENEGATTI 2024, p. 302.

2 VOLPE 1982.

3 SGARBI 1982, p. 3.

4 MEZZETTI 1965.

5 BALLARIN 1994-1995, I, p. 31, 299-300.

6 LUCCO 1998.

7 BALLARIN 1994-1995, I, fig. 170.

8 FRABETTI 1972, p. 36.

9 VOLPE 1982, p. 8.

10 Ibid, p. 6.

11 BALLARIN 1994-1995, p. 31.

12 MAZZA 1990, p. 271.

13 LUCCO 1998, p. 279.

14 FARINELLA 2008.

15 FRANGI 1992, p. 58.

16 GREGORI 1999.

17 FRANGI 1992, p. 34.

18 FRANGI 2022, p. 135.

19 BALLARIN 1990.

20 FARINELLA 2008.

Bibliography

A. Ballarin, Un profilo di Dosso (1990), in La “Salomé” del Romanino ed altri studi sulla pittura bresciana del Cinquecento, edited by B. M. Savy, Cittadella, 2006, pp. 197-216.

A. Ballarin, Dosso Dossi: La pittura a Ferrara negli anni del ducato di Alfonso I, Cittadella, 1994-1995, 2 vols.

V. Farinella, A problematic bronze relief by Antonio Lombardo (and a neglected document on Savoldo in Ferrara), in The Artistic Bronze Industry of the Renaissance in Venice and Northern Italy, Proceedings of the Conference, 2007, edited by M. Ceriana and V. Avery, Verona, 2008, pp. 97-100.

G. Frabetti, I manieristi a Ferrara, Milan, 1972.

F. Frangi, Savoldo. Complete catalog, Florence, 1992.

F. Frangi, Giovan Girolamo Savoldo: painting and religious culture in the early sixteenth century, Cinisello Balsamo, 2022.

M. Gregori, Savoldo Ante 1521: reflections for an unpublished “Crucifixion,” in “Paragone. Arte,” 1999, L, 23, pp. 47-85.

M. Lucco, [Anonymous padano (?) 58. Madonna in Glory and Angels with Saints Paul, Matthew, Catherine, Peter (?) and a Saint], in Dosso Dossi. Court Painter in Ferrara in the Renaissance, exhibition catalog, Ferrara September 26-December 14, 1998; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 14-March 28, 1999; Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, April 27-July 11, 1999, edited by Peter Humphrey and Mauro Lucco, 1998, Ferrara, pp. 276-280.

A. Mazza, [IV. 16 a Madonna and Child in Glory and Saints Matthew, Paul, Catherine of Alexandria and Other Saint] in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo: tra Foppa, Giorgione e Caravaggio, exhibition catalog, Brescia, Monastero di Santa Giulia, March 3 - May 31, 1990 and Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle, June 8 - September 3, 1990, edited by B. Passamani, Milan, Electa, 1990, pp. 270-271.

M. Menegatti, Giovanni Luteri detto Dosso, in Il Cinquecento a Ferrara: Mazzolino, Ortolano, Garofalo, Dosso, exhibition catalog, Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, October 12, 2024 - February 16, 2025, edited by V. Sgarbi and M. Danieli, Ferrara, 2024, pp. 301-311.

A. Mezzetti, Il Dosso and Battista ferraresi, Milan, 1965.

V. Sgarbi, 1518: Cariani in Ferrara and Dosso, in “Paragone. Arte,” 1982, XXIII, 389, pp. 3-18.

C. Volpe, An altarpiece by the young Dosso, in “Paragone. Arte,” 1982, XXIII, 383-385, pp. 3-14.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.