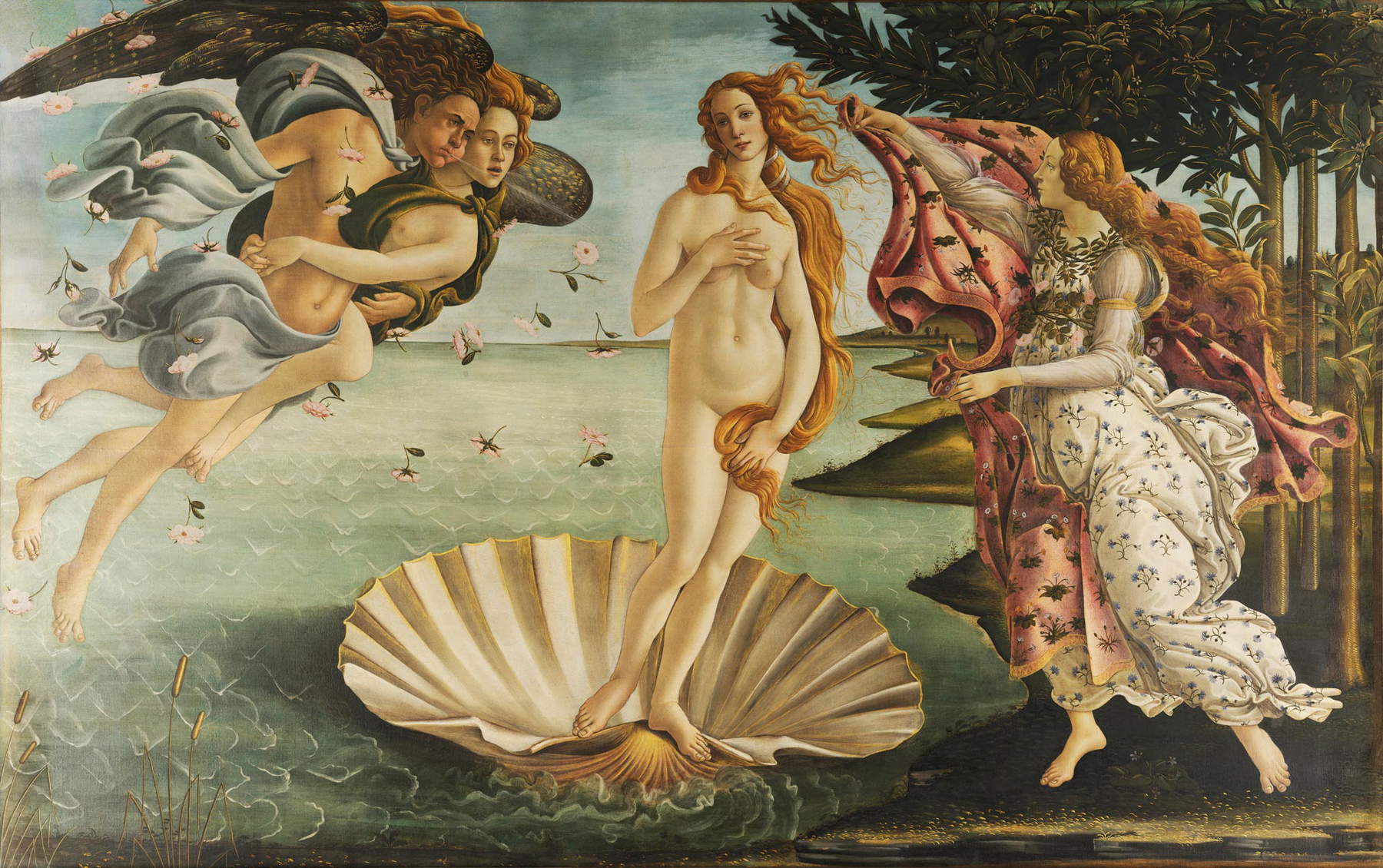

When one thinks of a work of art that succeeds in embodying the essence of spring, probably the image that will most easily come to mind will be that of Botticelli’s Primavera , at the risk of being a bit trite. Few paintings, however, have reached the status of universal icon like the splendid panel painted around 1480 by Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi; Florence, 1445 - 1510), not least because Primavera is one of the most recognizable images of the Florentine Renaissance and, more generally, the Italian Renaissance. Why is this work so special, so innovative, so famous? It is necessary, in the first place, to reweave the threads of its history. It is a work commissioned by the Medici: it is certain that in the early sixteenth century it was located at the Medici Villa of Castello, along with the Birth of Venus, because that is where Giorgio Vasari saw it, as the great historian from Arezzo reports in his Lives, and in particular in his biography of Sandro Botticelli: “For the city in several houses he made roundels by his own hand, and naked females very much, of which today still in Castello, villa of Duke Cosimo, are two figured pictures, the one Venus being born, and those auras and winds that make her come to earth with the loves, and so another Venus that the Graces flourish her, dinotating the spring which by him with grace are seen expressed.” And from Vasari’s description also derives the title Primavera by which the painting is universally known.

On Primavera, however, we have some more information than on the Birth of Venus. The work is in fact mentioned, as early as 1498, in the inventories of a palace in Via Larga in Florence owned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici known as the Popolano, from where it was later transferred to the villa in Castello, where Vasari must have already seen it in 1550, when the first edition of the Lives was published. The palace on Via Larga, which was near the Medici palace (the one now known as Palazzo Medici Riccardi), must therefore have been the work’s original location, although we do not know exactly when it must date from. And the dating is but one of many unsolved aspects of this painting, which is as famous as it is difficult to decipher with certainty, so much so that the great art historian Edgar Wind has called it an “unsolvable enigma.”

The image is well known: a group of characters, nine in all, dressed in the garb of Renaissance Florence (interpreted, however, in an “almost theatrical” key, as the scholar Charles Dempsey has noted), move against the background of a grove of orange trees, the Medici plant par excellence (in ancient times, the Latin name for orange was citrus medica, now used for cedar). A blue-skinned figure on the right is grasping a nymph covered only with the thinnest of veils: it is the wind Zephyrus, who seizes the nymph Clori, who after her union with the wind will become Flora, the goddess of spring, clad in a robe richly decorated with floral motifs, and painted as she is spreading roses at her feet. The union and subsequent transformation have visual evidence in the flowers that emerge from Clori’s mouth. The figure in the center is traditionally identified as the goddess Venus, although not all critics agree on this reading. Above her, flutters Cupid, the god of love, while at her side the three Graces, namely Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia, dance barefoot on the lawn, holding hands, also covered only in transparent veils. Finally, on the left, here is the god Mercury, waving his caduceus, the winged staff with snakes twisted in it, in the direction of some clouds that invade the left corner of the composition, probably to ward them off, thus making sure that no clouds, no rain can spoil this flowery spring. On the meadow, hundreds of plants that Botticelli studies individually, resorting to herbaria, the books that contained botanical knowledge: many of the plant essences are recognizable (Guido Moggi and Mirella Levi d’Ancona have devoted in-depth analyses to the plants that appear in Primavera, not least because they are often clothed with symbolic meanings), so much so that as many as 138 have been identified.

Primavera is a unique image, which Herbert Horne, in 1903, already called “unprecedented.” It is nevertheless an image that exudes classical antiquity. In developing his characters, Botticelli had to resort to ancient iconographic sources: for the main figure, that of the goddess conventionally identified as Venus, Botticelli perhaps had in mind some image of the Venus Victrix of Roman art: the figure of Venus Victrix, depicted in the same pose as Botticelli’s goddess, that is, with her right arm raised, her left arm descending along her hips, and her pose in opposition, with one leg on which the goddess unloads her weight and the other at rest instead (an example of a similar depiction can be identified in the Venus Victrix that adorned a funerary monument and which is preserved in the British Museum in London). The figure of Flora, as noted as early as 1893 by art historian Aby Warburg, a great exegete of Botticelli’s works, may instead derive from the Hora preserved in the Uffizi, a Roman statue in Carrara marble from the first century A.D., also identified as a depiction of Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruits: it was a work already known in Botticelli’s time. It has been speculated that Botticelli may have seen the two images during his 1481-1482 stay in Rome, when he may have had the opportunity to visit theantiquarium of the Del Bufalo collection (it has been also thought that the Uffizi’s Hora is the statue that once adorned the Del Bufalo garden), where there may also have been a relief or sculptural group with the Dance of the Graces that may have inspired Botticelli’s homologous group (a Roman sculpture in a similar pose, with one of the three deities seen from behind and the others dancing beside her, is now in the Vatican Museums). However, the pose of the goddess Flora also refers back to the type of Venus pudica, which certainly inspired the Birth of Venus, and was already widely known in 15th-century Tuscany.

Being the up-to-date artist that he was, Botticelli may also have drawn cues from contemporary sources. When looking at the figure of Mercury, for example, one might think of Donatello’s bronze David , executed about fifty years before Venus (the shoes the two figures wear are identical), or of the Mercury of the so-called “Mantegna Tarot” (actually by an unknown author), a series of playing cards made in the Ferrara area between 1465 and 1475 in two series called “E” and “S.” The insistent linearism of the figures has since led critics to find parallels with the reliefs of a great Florentine sculptor, Agostino di Duccio, such as those that can be encountered in the Malatesta Temple in Rimini. The fineness of Botticelli’s work is due above all to the movements of the lines that animate the figures and, together with the scansion of the figures themselves, give the scene its unmistakable rhythm, a cadence reminiscent of a poem translated into images, as well as to the brilliance and delicacy of the colors (the transparencies achieved through skillful and subtle veiling, such as those that conceal and at the same time reveal the features of the three Graces, are another of the distinctive features of Primavera) and to the clear light that uniformly illuminates the entire scene. In more recent times, scholar Max Marmor has provided an interesting visual parallel for the Primavera, linking it to the description of the Earthly Paradise in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy , which Botticelli knew very well (in fact, he even had the opportunity to illustrate it), especially through Cristoforo Landino’s commentary on Dante, also published in the edition of the Comedy illustrated by Botticelli himself. In this sense, Botticelli may have been inspired, according to Marmor, by an image now in the British Library, an illustration of the Earthly Paradise in the Yates Thompson Codex of the Divine Comedy, a preciously illustrated manuscript in mid-15th-century Siena that may have inspired Botticelli, at the very least, in the rhythmicity of his composition, given certain similarities. Why would Botticelli have been inspired by this illuminated codex to compose his Primavera? First, because that image could have been the basis for transforming a convention of fifteenth-century decoration on a monumental scale. And then, to offer visual evidence of what Marmor believes is the meaning of the painting, at least according to his theory, as will be seen below.

Roman art

Roman art

It is on this ground, then, that one must try to find the meaning ofBotticelli’sPrimavera . There are few fixed points: the laurel plants(laurus in Latin) refer to the name of the patron, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, about whose identification there should no longer be any doubt. The orange trees, again, denote commissioning from the Medici sphere. The gesture of the goddess in the center of the painting, with her right hand slightly raised, is a kind of greeting to the relative, a form of welcome, an invitation to enter this wonderful, lush garden. Critics have always thought that Botticelli drew on a variety of sources to compose his image: “It could be said,” Frank Zöllner has written, "that Primavera and the figures it contains are largely inspired by a bold combination of various textual fragments. Few other masterpieces are based on such a deliberate combination of literary sources. It seems almost possible to sort these texts on the basis of their importance to the painting’s message." The first to address the exegesis of Primavera was, in 1888, literary historian Adolf Gaspary, who proposed relating Sandro Botticelli’s image to Agnolo Poliziano’s poem in octaves, the Stanze per la giostra del magnifico Giuliano di Pietro de’ Medici, written, after 1478, to celebrate the victory in a tournament, held in Florence’s Piazza Santa Croce on January 29, 1475, of Giuliano de’ Medici, younger brother of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who had organized the contest. There is indeed an image that seems fitting: “Ma fatta Amor la sua bella vendetta, / Mossesi lieto pel negro aere a volo, / E ginne al regno di sua madre in fretta, / Ov’è de’ picciol suoi fratei lo stuolo: / To the realm where all Grace delights, / Where Biltà of flowers to the crin makes brolo, / Where all lascivious, drieto a Flora, / Zephyrus flies and the green grass flourishes. // Now sing with me a little of the sweet realm, / Erato bella, che ’l nome hai d’amore; / Tu sola, benché chaste, puoi nel regno / Secura entrar di Venere e d’Amore; / Tu de’ versi amorosi hai solo il regno, / Teco spesso a cantar viensi Amore; / E, posta giù dagli omer la faretra, / Tenta le corde di tua bella cetra.” Gaspary introduced the character identification best known, and long never again questioned. The literary reference to Poliziano’s text could have introduced a dynastic interpretation: according to Aby Warburg and, later, Adolfo Venturi, Mercury would allude to Giuliano de’ Medici (also by virtue of the fact that inverted flames appear on his chlamys, a symbol of death as Edgar Wind noted, but also an allusion to the “flaming broncone,” a Medici feat), while Flora to her beloved, Simonetta Vespucci, and the painting would arise as a kind of celebration of the union between the two lovers, all according to Poliziano’s direction. “If we assume that Poliziano was asked to show Botticelli how to enshrine Simonetta’s memory in a pictorial allegory,” Warburg writes, “then he must have had to take into account the specific representational requirements of the painting. This led him to assign the individual features stored in his imagination to some specific mythological characters, so as to suggest to the painter the idea of a single figure more clearly defined and thus more easily represented, that of Venus’ companion, the Primavera.”

Two other merits still belong to Warburg: relating Spring to a passage in Ovid’s Fasti , which would have provided inspiration for Poliziano himself, and imagining Spring as a painting conceived together with the Birth of Venus. Thus, the Birth of Venus describes the moment when the goddess of love and beauty comes into the world by rising from the waters, while Spring , on the other hand, would be the moment when the goddess manifests herself in the world by making her appearance in the “realm of Venus.” Many other readings have arisen from this approach. According to Erwin Panofsky’s hypothesis, Venus and Spring should be read on the basis of a neo-Platonic philosophical framework, which refers to the thought of Marsilio Ficino. There would thus exist two Venuses, Venus coelestis, the celestial Venus, the image of ideal beauty, mediator between the human being and God, and Venus vulgaris, the earthly Venus, the image of beauty realized in the corporeal world, the symbol of generative force, like Lucretius’ Venus genetrix . The former Venus, accompanied byamor divinus, urges man to contemplate divine beauty, while the latter, accompanied byamor vulgaris, presides over the senses and urges human beings to procreation. In this picture, the Birth of Venus would allude to the heavenly Venus, while the Spring would be an image of the earthly Venus. Here, then, the Venus of Spring becomes the embodiment of human love; she becomes the Venus Humanitas that moves humanity toward loving feeling. According to this interpretation, the three Graces are the three elements of liberalitas, generous love: giving, receiving, corresponding (all read in relation to the Birth of Venus: divine love is granted to humanity, humanity receives it, and returns it to God in the form of devout contemplation). The Graces, however, have also been associated (notably by Edgar Wind) with three qualities of love: beauty, chastity, and pleasure, namely Pulchritudo, Castitas , and Voluptas, identifiable by their attitudes and elements: Pulchritudo with a jewel around her neck, Castitas in a resigned pose, Voluptas with her hair tousled and unruly. Flora, goddess of spring, on the other hand, represents the transition from active to contemplative life, from the temporal to the eternal, universal dimension. The Zefiro-Clori pair refers to the primordial force of passionate love, which undergoes the influence of Venus through Cupid and is then sublimated by the liberalitas of the Graces. Mercury, on the other hand, would assume the role of a deity who connects the earthly dimension with the transcendent one, acting as a guide for love to return it to its ideal sphere: in this sense, therefore, his gesture should be interpreted.

The reading of the two paintings as conceived in pendant on the common substratum of neo-Platonic philosophy, however, began to enter into crisis the moment John Shearman discovered the inventories of the palace in Via Larga in which Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici resided: the documents mention the Primavera and the Pallas and the Centaur, but make no mention of the Birth of Venus, a circumstance that has led some critics to rule out that the paintings were conceived together.

With the discovery of the link between the Primavera and the commissioning of the Popolano, the possibility of strong links to the story of Giuliano de’ Medici has also been questioned. In this sense, Mirella Levi D’Ancona’s reading is interesting, according to which the painting may indeed have been conceived for Giuliano de’ Medici, but may then have changed meaning after the death of the Magnifico’s brother in the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478. Initially, according to Levi D’Ancona, the painting was meant to celebrate the union between Giuliano and the mother of his son, Fioretta Gorini (the son, Giulio Zanobi de’ Medici, destined to become Pope Clement VII in 1523, was born on May 26, 1478, and never met his father, who was assassinated exactly one month earlier). Giuliano would therefore have been represented by Mercury and Fioretta by Venus, after which, following Giuliano’s disappearance, the painting would have been “converted” into an allegory of the marriage between Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici and Semiramide Appiani, celebrated in 1482 (a thesis, that of the Primavera painted on the occasion of this marriage, which had already been formulated by Ronald Lightbown): the Commoner would thus be portrayed as Mercury, his wife would assume the guise of Grace in the center, and Venus would return to embody her role, that of the goddess “presiding over all forms of love,” writes Levi D’Ancona. The bond that would unite all nine figures would become Ficino’s theory of Love: "on the right , the seduction of Clori would representAmor Ferinus, the lowest form of love, which unites man with the beast. On the left, the central Three Graces would representAmor humanus in the person of Semiramis Appiani, who fixes her gaze on her bridegroom; while Mercury turns his back on all that belongs to the earth, crossing the clouds of ignorance with his caduceus to reach Divinity; and would representAmor Divinus." Also according to this reading, Flora should be interpreted as the personification of marriage: indeed, there would be many references to the theme of marriage, starting with plants (myrtle above all) that would be associated with conjugal love, or fertility. Frank Zöllner also agreed on the idea of a nuptial picture.

Scholar Max Marmor, similarly agreeing on the idea that the painting may have originated on the occasion of the marriage between Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici and Semiramide Appiani, proposed an interesting “Dantean” reading of the painting, thus also trying to extend the answer as to why Botticelli may have been inspired by a 15th-century illustration of the Earthly Paradise from the Comedy. An “old-fashioned earthly paradise,” Marmor called it, which discerns the painting’s philosophical theme in the “moral and spiritual pilgrimage of the soul” of Cristoforo Landino’s commentary on Dante: the pilgrimage from the voluptuous life to the contemplative life through the vita activa. We return, then, to the terrain of Neoplatonic philosophy, albeit expressed through Dante’s poem. Botticelli would thus have given substance, through the characters of mythology, to the concepts expressed by Dante in Purgatorio. It would remain to be understood why Botticelli resorted to myth in order to present a Dantean image to the patron: according to Marmor, it is because Cantos XXVII-XXVIII of Purgatorio are rich in images drawn from the mythological repertoire (Venus herself is mentioned in Canto XXVIII), and because the expedient would allow Botticelli to link the ancient world to the Christian world. Not only that: during the encounter between Dante and Matelda, in canto XXVIII, the young virgin evokes to the poet the image of a perpetual springtime that makes Paradise on Earth bloom eternally. The group should therefore be read in this way: the figures on the right (the “gentle wind” in canto XXVIII) represent voluptuous life; the three Graces (“Three women around by the right rail / venian danzando,” in canto XXIX) are allegories of the three theological virtues (faith, hope and charity) that have the task of guiding Dante from the activa life to the contemplative life, represented by the figure of Mercury whose gesture still echoes an image from Dante’s Canto XXVIII (“I will purge the fog that fogs you”).

There have also been attempts to interpret Primavera as an allegory of the golden age of Medici Florence, or as a representation of the months of spring (according to Charles Dempsey, Zephyrus, Chloris and Flora represent the month of March, Venus, Cupid and the Graces are allegories of the month of April, and Mercury finally represents May). Among the more recent interpretations it is certainly worth mentioning that of Giacomo Montanari, already extensively explored on these pages, according to whom Primavera should be read in the light of the entire passage from Ovid’s Fasti quoted by Warburg: the traditional readings, in fact, as also mentioned above, argue that Botticelli made a broad collage of different literary sources. Instead, according to Montanari, it is more likely that the artist relied on a single text: thus, if the first part (Zephyrus seizing Clori and marrying her, making her Flora) is in agreement with traditional readings, the central goddess, following Ovid’s Fasti , would, on the contrary, be Juno, the wife of Jupiter, who asks Flora for help in impregnating her: Flora, in Ovid’s text, touches the belly of the goddess (which, by the way, is slightly prominent in Botticelli’s image, perhaps signaling pregnancy) making her pregnant with Mars. And the myth of the birth of Mars is closely linked to Florence, since the city attributed its mythological foundation to the god of war (so much so that Mirella Levi D’Ancona was surprised that hints of this myth were absent from the painting). Also linked to Juno are the orange trees: they are in fact the gift Juno received on the occasion of her marriage to Jupiter, and which she would plant in the Garden of the Hesperides (which would thus become the setting for Botticelli’s work). The Graces are included in the Ovidian tale, while the figures of Mercury and Cupid would remain to be resolved. Cupid, god of love, is present in that without love Juno cannot give birth. Mercury, finally, would be the heavenly Mercury of the Neo-Platonists, personification of the spirit hovering over the world, an entity that binds the earthly world to the divine.

What became of the Spring after it left the palace on Via Larga? For some time it remained in the Villa Medicea di Castello, where Vasari, as recalled, had certainly seen it before 1550, along with the Birth of Venus. The work never left Florence, at least as far as we know: in 1815 it is mentioned in the Medici Guardaroba, after which, in 1853, it was transferred to the Galleria dell’Accademia. Finally, since 1919, it has been kept at the Uffizi, where it can still be admired today, in the same room that holds the Birth of Venus. The dating remains controversial: some critics, as mentioned, associate it with the marriage between Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici and Semiramide Appiani, thus placing it in 1482, while others believe it was painted before Botticelli moved momentarily to Rome in 1481 (it would thus be painted around 1480), and still others move the placement slightly forward, going up to 1485. Not to mention that in the past there were those who proposed an even higher chronology, to 1478, the year of the Stanze di Poliziano.

Dating, of course, is not the only aspect yet to be clarified about this work. One of the most celebrated images in art history, yet so complex, so mysterious, so elusive in meaning. It is likely that perhaps, in the future, new discoveries will help clarify its meaning: when the inventories of the palace on Via Larga were discovered, perspectives on the painting also changed. It cannot be ruled out that new discoveries of this kind will be able to shed more light on Sandro Botticelli’s masterpiece, the very icon of the season of flowering, of rebirth. At the moment, we can just content ourselves with discussing hypotheses, about which we think is the most likely, or the most fitting. For now, as Federico Zeri said, “the true meaning of Primavera remains locked in a hieroglyphic whose Rosetta stone has perhaps not yet been found.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.