Ruins as warning and memory: the Platonic Oath and the Acropolis of Athens

In 1945, theArchitectural Press in London published a book of a few pages entitled Bombed Churches as War Memorial. The pamphlet argued that ruined churches damaged by the bombs of war should remain as such so that they could be transformed into visually striking cultural monuments for the entire population and future generations. However, the idea of converting them into memorial sites took hold several years after the end of World War II. In May 2017, the Donald Insall Associates company, led by architect Donald Insall, finished work at St. Luke’s Church in Liverpool built in 1832, also known as St Luke’s, The Bombed-Out Church. The company was responsible for addressing material degradation problems that had occurred in the ruined building that had been hit by incendiary devices in 1941. The project consisted of removal of invasive vegetation, repair and reconstruction of the upper masonry, and enhancement of the sanctuary through an architectural lighting system; interventions that led to the building’s removal from the Register of Structures at Risk, known as the Heritage at Risk Register, published by Historic England.

Despite the curation treatment of the ruin, the English landscape tradition, dating back to Romanticism, associated the concept of rubble with natural decay and man’s helplessness in the face of nature, claiming that even bomb damage was somehow picturesque, as stated by Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London, in the Times newspaper in 1944. That year, the newspaper published a letter signed by several prominent figures arguing that destroyed churches should be preserved in their own condition as memorials to the war. According to the modern man, referring to the current of English Romanticism, the archaeologist’s task is therefore not to preserve or rebuild the destroyed site, but to understand, assimilate and make the ruin totally his own, which becomes a work of art charged with feeling and does not fit into modern archaeology. “A ruin is more than a collection of debris. It is a place with its own individuality, charged with its own emotions, atmospheres and dramas, its own grandeur, nobility or charm,” said Rose Macaulay in her 1984 Pleasure of Ruin - “The Pleasure of Ruins.”

For the Greek people, the concept and process of memorializing sacred places and the exhibition spaces within those places were no different. After the Second Persian War and the Battle of Plataea, which took place in 479 B.C., during which Athens was sacked by the Persian army of Xerxes I, the Greeks decided, through a clause called the Plataean Oath, not to rebuild either the acropolis of Athens or the temples destroyed by the enemy army. What was the purpose of the Oath? Among the various codes of honor described in the covenant, based on the foundations of democracy, the main purpose was to leave the temples and sacred structures in the state of ruin and destruction they were in, so that every person could see the sacrilegious and blasphemous act that the Persian people had so cruelly committed against Greece. We are left with written proof of this by the Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus in his translated text of the Oath: “[...] And of the temples destroyed by the barbarians I will not rebuild a single one at all, but I will leave them for posterity as a reminder of the ungodliness of the barbarians.”

For the Greek people, the Acropolis held unparalleled importance. The site, situated on hills that formed the upper part of the city, dominated every other area, for since the Mycenaean age it had been reserved for the defense of royal residences, similar to our medieval castles. The Acropolis was thus born with a governmental and political function, in a strategic location. Not surprisingly, its etymology comes from the ancient Greek “akros” and “polis,” words meaning “high city.” It was in the palace on the hill that the king of the city lived. Beginning in the 6th century B.C., the function of the Acropolis changed. Royal buildings and political activity were moved within the agora, the city’s main square, leaving the Acropolis the honor of housing shrines and votive statues of the deities who protected the city. The transformation emphasized the Acropolis’ role as a religious and cultural, rather than political, center, making it a symbol of great spiritual and identity value to the Greeks.

Although in general the transformation from political to religious center had to wait another century to become established, as early as around the 7th century BCE, during the Archaic Age, the Acropolis of Athens served a sacred function. Not much is known about the various buildings on the high ground, but we can say that there was already an early Parthenon, commonly called the Old Parthenon, located on the present sanctuary, and the ancient Temple of Athena Polias (529-520 BC), a work built under the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus (600-528/527 BC). The temple, located between the present-day Erechtheion and Parthenon, is believed to have housed a wooden statue, a xoanon (cult image) of Athena Polias.

Pisistratus is also credited with the construction of the second (in time line) monumental entrance to the Propylaea (437-432 B.C.) in white Pentelic marble, which followed those of Mycenaean origin, which were later followed by those built by Pericles. The Archaic Acropolis also housed numerous sculptures of deities, votive works, and the painted insular marble Kouroi and Korai series, a group of male and female statues from the second half of the sixth century BC, now housed at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. With the Battle of Plataea, the Persians plundered Athens and destroyed the Acropolis: its temples, statues, walls and Propylaea were razed to the ground. They beheaded the votive sculptures, reducing the Acropolis and Athens itself to a heap of rubble and dust, dust that tasted of pain, anger, and fire, carried away by the wind. With the devastation of the Acropolis, the Persians deliberately obliterated the memory and heart of the city, accomplishing a violent shattering of Greek identity. The debris of the Acropolis therefore has nothing to do with the Romantic poetics of the nineteenth century. For the Greek people, showing the world the affront they suffered through the Platonic Oath had no romantic traits: the ruins of beheaded statues and burned temples never became works of art, nor did they anticipate the picturesque aesthetic used to represent and photograph the bombed churches of 1945. Yet the quiet, dramatic language of the Greek response managed to symbolically raise a clear message, which Aeschylus encapsulated in 472 B.C. in the tragedy The Persians: theHybris, the arrogant pride and titanism of the Persians become the example of the pride of Xerxes I, the cause of his own defeat, at the hands of Nemesis, the consequent divine vengeance: “[...] There atrocious sufferings await them, and it will be the punishment for their pride, for their impious boldness. For these are they who, having come to Greek soil, had no restraint to prey on the idols of the gods, to set fire to the temples: altars devastated, sacred statues torn down and thrown to the ground, in bulk. Those who did evil, suffer as much, not less! [...] Heaps of corpses up to the third generation will teach that those who are mortal must not be too haughty [...] Watch therefore the doom of this enterprise and always remember Athens, remember Greece!”

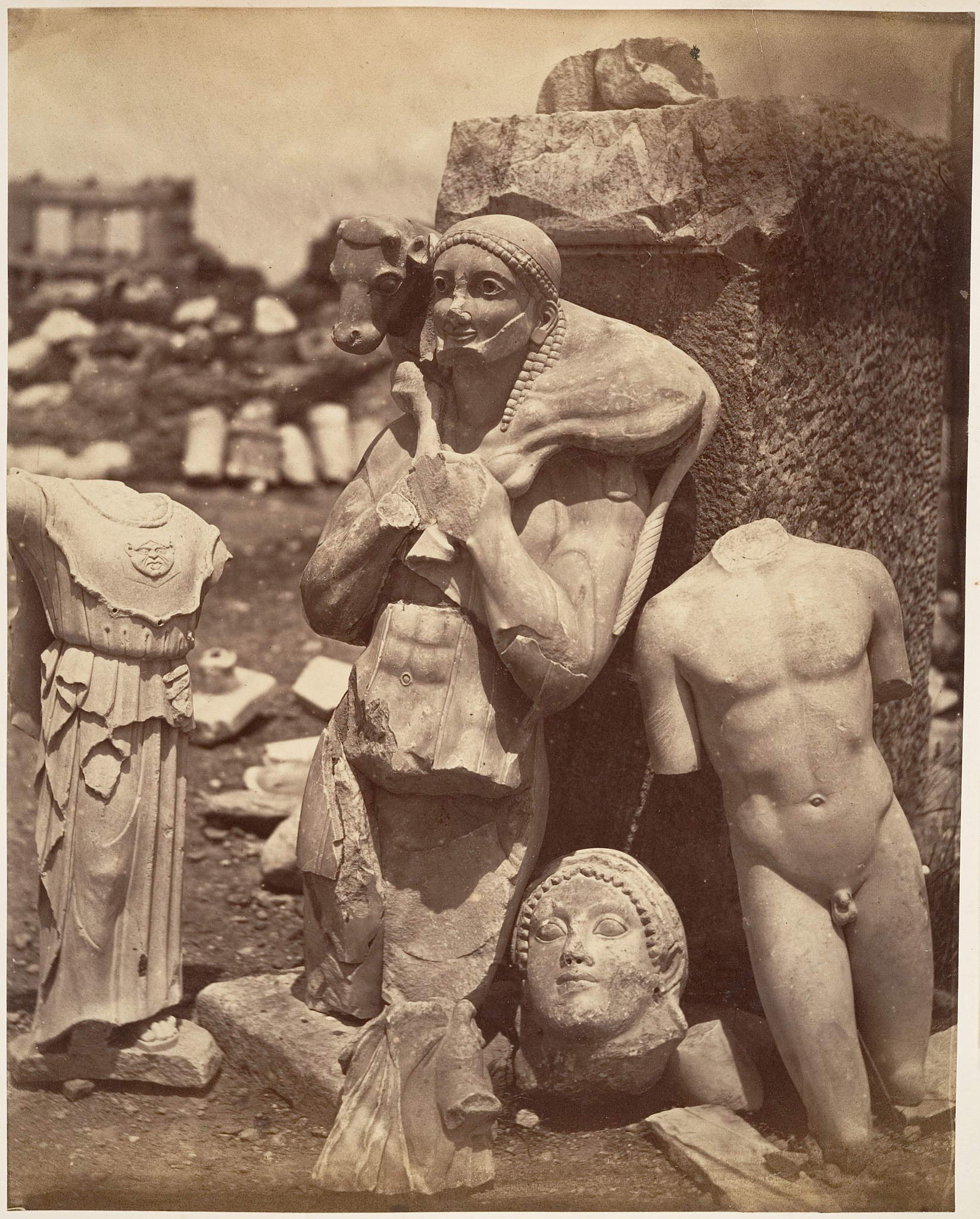

The Platonic Oath held for several years, but it did not represent the final solution for the future of the Acropolis. None of the ruined temples ever became a war memorial. In 447 B.C., in order to rebuild the Acropolis, the entire group of mutilated archaic sculptures, which could neither be thrown away as garbage nor could they leave the perimeter of the sacred area, were placed under a mound of earth in the foundations of the new Acropolis, in different spaces: in the west and north area of the new Parthenon, in the south area and in a space between the wall and the rock. During archaeological expeditions and alterations to the Acropolis in the nineteenth century, the entire sculpture complex was found around 1863 and is still the largest find from the Archaic period, bordering on the severe and classical style of Greek art. The buried pile of rubble and votive materials took the name Persian Colmata, or Perserschutt in German.

Among the remains found, still bearing signs of burns and vandalism, are such works as the Moschophoros in marble, once polychrome, the striking Kore of Euthydikos also in marble, dating from 490-480 BCE, Kore with the peplos, the Rampin Horseman, and theAthena Angelitos in Pentelic marble. Today, the Persian Colmata finds represent an important part of the group of works housed at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. In 1997, German archaeologist Astrid Lindenlauf described the Persian Colmata as “an esplanade of uniform rubble caused by the Persians that was later exploited by the Athenians according to a plan of rearrangement and reuse for construction and terracing on the Acropolis in the years after 480 BCE.”

Different from the excavations and sculptural votive finds, however, are the discoveries related to the rubble and remains of the temples and architectural structures named Tyrannical Colmata - Tyrannenschutt. In fact, the term refers to structures built during the Greek tyrannical period. Among the buildings discovered to the south and southeast of the present Parthenon, archaeologists found poros portions of pediments, such as the Hydra pedi ment and the pediment of the apotheosis of Heracles, which are still well preserved, as well as various archaic architecture and small temples such as the Dörpfeld which belonged to the temple of Athena Polias and were so named in honor of the German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld (Barmen, 1853 - Lefkada, 1940), who discovered and analyzed them. The Persian and Tyrannical Colmata phenomenon attracted archaeologists and artists from all over the world. One of these was the architect Le Corbusier (La Chaux-de-Fonds, 1887 - Cape Martin, 1965), who emphasized the importance of the Acropolis and its ruins in the world architectural context. Le Corbusier was fascinated by the light, the linear forms of the surfaces, and the beauty of the Greek landscape. These impressions brought him closer to the thinking of great Greek architects such as Dimitris Pikionis (Piraeus, 1887 - Athens, 1968), who decided to intervene around the Acropolis with a project to enhance the spaces and ancient streets, working on the concept of universal Greek memory. His project, the Athens Acropolis Walk (1954-1957), aimed to harmoniously integrate the past and the present, respecting Greek history and culture.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.