Rubens in Flanders, the four great masterpieces in Antwerp Cathedral.

When the great Scottish writer Walter Scott (Edinburgh, 1771 Abbotsford House, 1832) visited the city of Antwerp in 1815, soon after Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, he found the Cathedral of Our Lady still bare of its masterpieces. The author of theIvanohe lamented, in particular, the absence of the splendid works by Pieter Paul Rubens (Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640), which a few years earlier had been plundered by the French occupiers and taken to Paris, but at the same time he trusted in the diplomatic skills of King William I of Holland to return the works to their home: “he has lately promised to use all his influence to recover the paintings that have been removed from the various churches in the Netherlands, and especially from Brussels and Antwerp.” The hope was well placed, for as early as 1816 all the Rubens masterpieces from Antwerp Cathedral had returned. Since then, the works of the great Flemish artist have not moved.

There are four major Rubens masterpieces in the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal in Antwerp, and they are all large-scale and of primary importance for framing the artist’s style: they were in fact executed shortly after Rubens’ return from Italy, where he had stayed until November 1608 (when he had to return to Antwerp to care for his ailing mother, who nevertheless disappeared while the painter was traveling), and are therefore steeped in Italian culture. Rubens had returned to Flanders, his homeland, at a time that was decidedly prosperous from an economic point of view: this climate, Flemish art historian Frans Baudouin has pointed out, fostered a remarkable artistic momentum, since the guilds, or associations of artisans and merchants, as well as the aristocrats and wealthier bourgeoisie, wanted to demonstrate their wealth by commissioning numerous works of art from the most prominent artists of the day. Rubens was thus overburdened with work, not least because in 1609 he had been appointed court painter by Archduke Albert of Habsburg, prince of the Southern Netherlands: this was therefore a particularly happy time for the artist’s career, which was engaged as much in secular achievements as in paintings with sacred themes. Regarding the latter, Rubens showed himself to be very sensitive to the theological stresses of his time: his works aim at the direct involvement of the faithful, either by making them participate intensely in the drama of Christ (of the four paintings in the Cathedral, two depict moments of the Passion), or by leading them to meditate on the mysteries of the Christian faith. The very choice of the main subjects of the works reflects the principles of the Counter-Reformation, since the paintings, rather than being centered on the patron saints of the patrons (who are given a subordinate role in the compositions: they are, for example, included in the predellas, or appear at the sides of the most important scene), insist on the different moments in the life of Jesus or, as in the case of theAssumption of the Virgin, the last painting made for Antwerp Cathedral, offer the viewer spectacular scenes that, accomplice also to the enormous dimensions (with the exception of the triptych of the Resurrection, these are works always above three meters in height), capture him and make him participate in what unfolds before him.

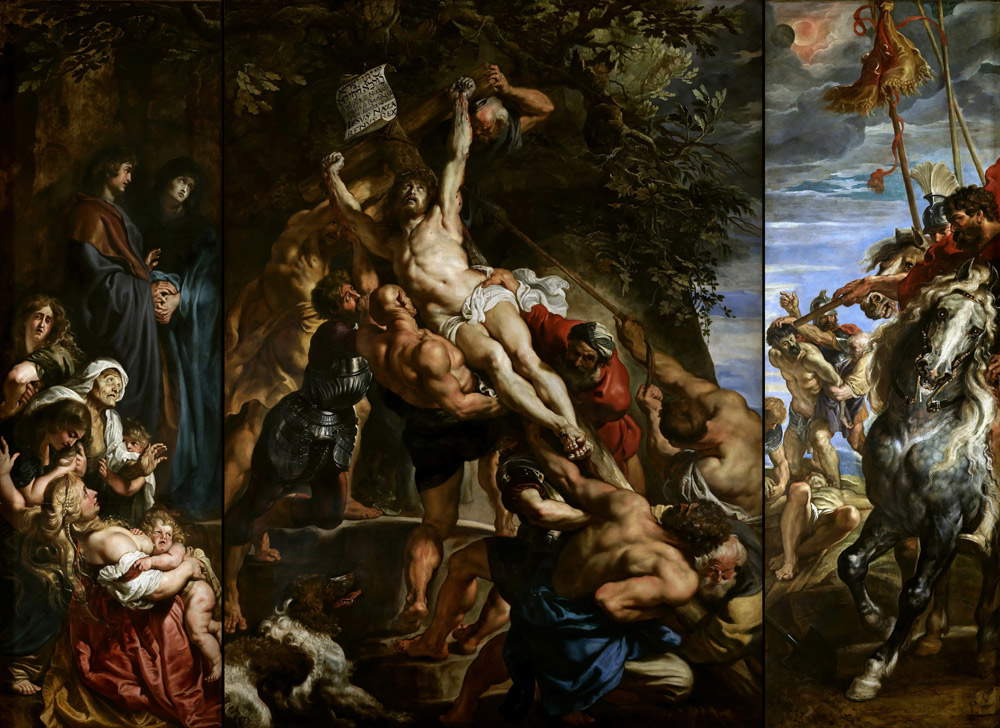

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens’Raising of the Cross, one of his works in Antwerp Cathedral. |

As anticipated, there are four works by Pieter Paul Rubens preserved in the Antwerp Cathedral: the triptych of the Raisingof the Cross, created between 1610 and 1611 (this is the only one of the four paintings that was not originally executed for the Cathedral), the triptych of the Resurrection, which Rubens waited for between 1611 and 1612, the triptych of the Deposition (painted between 1611 and 1614), and finally the altarpiece of theAssumption of the Virgin, which the artist finished in 1626. The earliest of the four works, theElevation of the Cross, was originally conceived for the church of St. Walpurga in Antwerp, which no longer exists today: it was in fact demolished in the early 18th century, and it was at that time that it was decided to transfer Rubens’ masterpiece to the main church in the capital of Flanders. The work was allotted to him in June 1610 by the parishioners of St. Walpurga, who were eager to decorate the new high altar with a significant painting. Painter and patrons thus met that summer at a tavern, Klein Zeeland, to sign the contract, which earned the artist the sum of 2.600 florins (a considerable sum, if one considers that Rubens received, as a wage base for his role as court painter, five hundred florins a year, in addition to receiving additional payments for individual works anyway): the parishioners included the wealthy and powerful spice merchant Cornelis van der Geest (Antwerp, 1577 - 1638), who was a friend of Rubens and played a decisive role in guiding the choice of the parishioners of St. Walpurga on the name of the artist who was to take charge of the work. And the choice could not have turned out to be better, for Rubens executed something that had never before been seen in Flanders: an innovative, revolutionary work, “revealing,” wrote art historian Charles Scribner, “Rubens’s early Baroque aspirations, laden with the spirit of Tintoretto and that of Michelangelo, as well as the Hellenistic model of the suffering hero, the Laocoon.”

The triptych of theElevation of the Cross is surely the most powerful and energetic of Rubens’ works in Antwerp Cathedral: In the main scene, against the backdrop of a landscape of rocks covered with lush tree foliage, a muscular Jesus has just been nailed to the cross and raises his gaze worriedly upward, while his equally nerveless tormentors (there are as many as eight of them, of all ages), straining bare-chested or at most clad in simple tunics or, in the case of the soldier on the left, shining armor, pull the ropes and support the wood to lift the cross. It is a kind of maelstrom of bodies, muscles and fatigue, arranged around the diagonal created by the cross and in which we seem to be present in the first person, not least because all the directions of the work channel the viewer’s gaze toward Christ, who is looked at with dismay even by the characters who crowd the left panel. The slender, waxy-faced Madonna is in the upper part of the composition, watching with an expression imbued with deep melancholy, inwardly meditating on her grief, and she is accompanied by St. John who tries to calm her by caressing her hands, while Magdalene is visibly distraught and constitutes the apex of a pyramid of characters formed by mothers with children shedding tears in front of the terrible scene. In the right panel, on the other hand, we see two Roman centurions who arrive on horseback and order the thugs to lift the cross, while we glimpse others, in the background, engaged in nailing with brutal force the two thieves who will shortly thereafter suffer the same fate as Jesus (one of them is about to be violently thrown to the ground: we see him being forced with one knee to strike the face of the one who is already lying down). Rubens introduces in this Raising of the Cross a number of devices intended to engage the viewer directly: the absence of the crowd that was typically included in homologous scenes, the reduction of the depth of space to make the scene appear even closer to the viewer, the accentuation of chiaroscuro to give a greater impression of three-dimensionality (the executioner at the bottom, grasping the cross at the lower end of the vertical arm, has a shoulder that almost seems to come out of the painting).

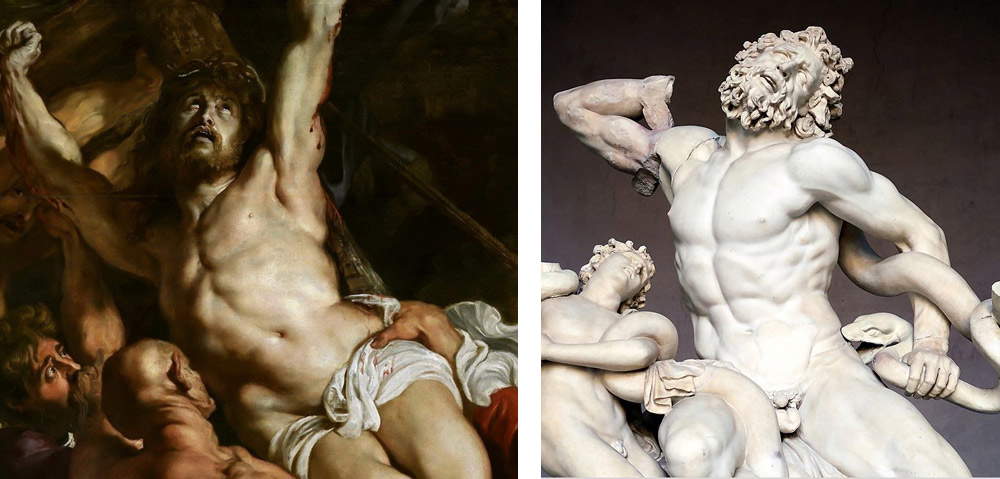

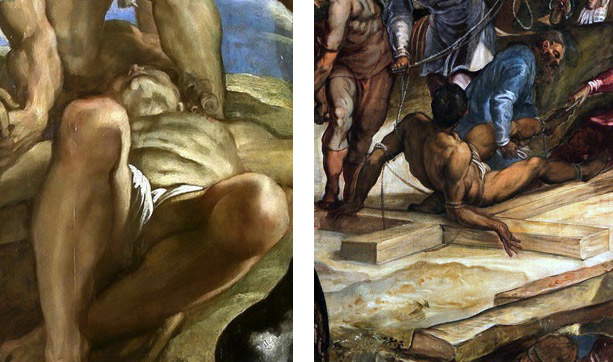

This was a work that also served an important symbolic function in Catholic Flanders: the physical presence of Jesus behind the high altar of St. Walpurga’s church served to remind the faithful of the validity of transubstantiation, the Catholic dogma, denied by the Protestants and forcefully affirmed by the Counter-Reformation Church (including through the production of several paintings in which the consecrated host was the absolute protagonist), according to which the substance of the bread and wine are transformed by the priest into the true substance of Christ’s body and blood. For an early seventeenth-century believer, seeing such a scene behind the officiant was equivalent to observing the substantial presence of Jesus in the bread and wine offered to him at the moment of the Eucharist. And to best engage in the task of creating such a powerful work, Rubens resorted to Italian painters or classical statues that could offer him the most dramatic and pathos-laden examples. The muscularity of the bodies is evidently indebted to the figures in the vault of the Sistine Chapel painted by Michelangelo, the vivid colorism reveals Titianesque reminiscences, the idea of the executioners pulling ropes and supporting the cross with their bodies derives from Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St. Peter, the twisting of Jesus’ torso is identical to that of the celebrated Laocoon group, and again the Crucifixion painted by Tintoretto for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in addition to providing cues for the heated tension and luminism endowed with narrative character, also offered suggestions for certain details such as the centurion arriving on horseback, the henchman supporting Jesus’ cross with his arms placed diagonally, and the thief still on the ground as he is nailed to the cross. The attention to detail, typical of Flemish art, is seen especially on the verso of the two side panels, which can be seen when the triptych is closed: in the left panel we find St. Amandus and St. Walpurga, and in the right panel St. Eligius and St. Catherine of Alexandria.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross (1610-1611; oil on panel, central panel 460 x 340 cm, side panels 460 x 150 cm; Antwerp, Cathedral of Our Lady) |

|

| Comparison of Rubens’ painting with Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St. Peter |

|

| Comparison of Rubens’s painting and the Laocoon |

|

| Comparison between Rubens’ painting and Tintoretto’s Crucifixion |

|

| Comparison between Rubens’ painting and Tintoretto’s Crucifixion |

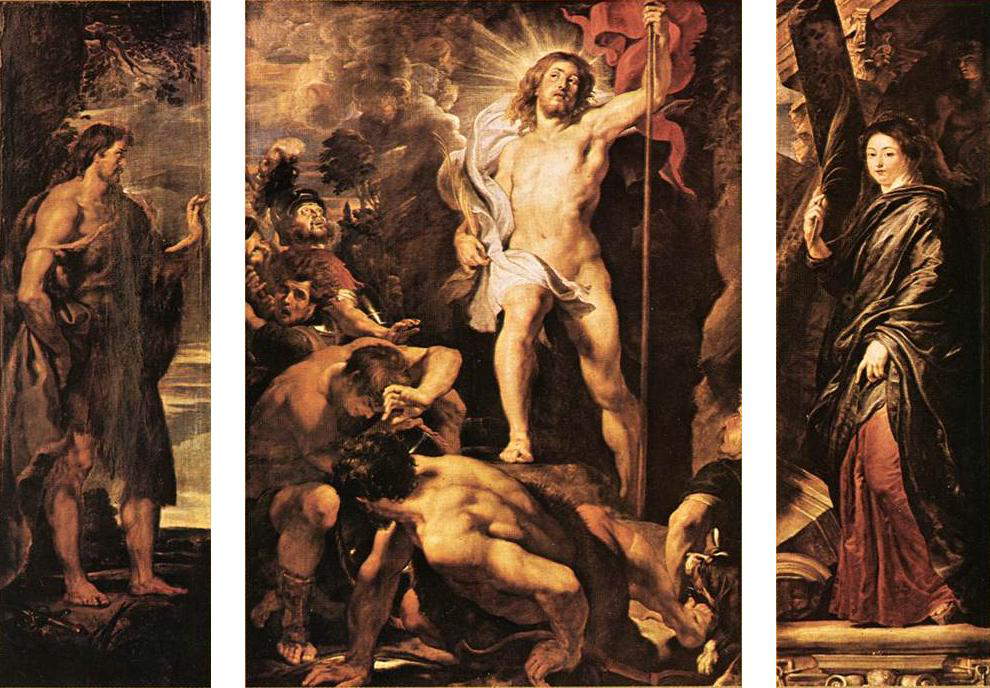

We have to imagine that theRaising of the Cross had caused quite a stir in the city and led Antwerp’s most up-to-date patrons to realize the overwhelming scope of Rubens’s Baroque, if as early as 1611, when the artist had yet to finish the work, two more requests came to him. The first he accepted was that of the gentlewoman Martina Plantin, widow of the printer Jan Moretus: she wished to remember and pay tribute to her husband with a work to be destined for the second chapel of the Cathedral, where Moretus (who, moreover, was a friend of Rubens) lay buried. The theme chosen for what would become the first work Rubens executed for Antwerp Cathedral was the Resurrection of Christ, a particularly appropriate and popular iconographic subject for a deceased person. Again the triptych format was chosen, with the main scene in the center and, in the side panels, Saints John the Baptist and Martina, the eponyms of the couple, set in a landscape similar to the one we find in the background of the main compartment, but still disconnected from the main scene. The two saints are depicted with their typical iconographic attributes: John the Baptist with the camel’s hair tunic, with which he would have covered himself during his penitential wanderings in the desert, the Jordan River (an allusion to Jesus’ baptism), and the sword, which refers instead to his martyrdom. Martina is depicted in front of the ruined temple of Apollo: in fact, legend has it that the building collapsed while she was making the sign of the cross. The outside of the panels, on the other hand, features angels in grisaille.

The Resurrection shows a scene that fits into the more typical iconographic tradition on the theme. Christ is depicted on the right in the act of emerging from the tomb, imperious like a commander of an army, looking upward, his right leg advancing and his left hand holding the banner, a sign of victory, symbolically alluding to his triumph over death. His appearance is accompanied by a strong irradiation of light, whose rays dazzle almost to the point of blinding the soldiers in charge of guarding the entrance to the tomb, and who, faced with Jesus’ exit from the tomb, screen themselves with their hands, nevertheless showing amazement and disbelief at what is happening before them: this, too, is a typical iconographic motif of the resurrection theme. Again, as was the case in the earlier paintings, Rubens has isolated the figure of Christ by having the eye of the beholder focus on him, while the soldiers are arranged around, along the diagonal that starts from the lower right corner (where we find a dog, and a dog moreover was also present in theRaising of the Cross) and goes almost as far as the upper left corner. In this painting, Christ’s pose appears to mirror that of the Jesus who appears in Titian ’s Resurrection in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, and the gait resembles that of another Risen Christ by the Cadore painter, namely the one that appears in the Averoldi Polyptych: these are figures that Rubens probably must have had in mind when he was working on his Resurrection, a work that appears to have been finished in April 1612.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Resurrection (1611-1612; oil on panel, central panel 138 x 98 cm, side panels 136 x 40 cm; Antwerp, Cathedral of Our Lady) |

|

| Comparison of Rubens’ Risen Christ with those of Titian in the Resurrection in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche (center) and the Averoldi Polyptych (right) |

The second commission Rubens received while he was busy with the Resurrection was given to him by the guild of arquebusiers (in the local language Kolveniers), who asked the painter, for their chapel in the Cathedral, for a painting with the theme of the Deposition, another work to be conducted according to the triptych format. Again, Rubens’ friendships were decisive in obtaining the commission: the guild president was in fact Nicolaas Rockox (Antwerp, 1560 - 1640), former mayor of Antwerp and a friend of the painter. On September 7, 1611, the parties signed the contract, and the central compartment was ready a year later, while for the lateral ones, depicting respectively the Visitation and the Presentation in the Temple (in the latter, note the presence of Rockox, who wanted to be depicted kneeling in front of the protagonists), the commissioners had to wait until 1614. The patron saint of the guild of arquebusiers was St. Christopher, and the theme of the Deposition was chosen precisely to evoke the saint’s name (which in Greek literally means “the one who carries Christ”), since the characters in the painting, above all St. John, whom we see in the lower right corner, actually “carry” the body of Christ from the cross to burial. In essence, it was as if the painting was composed of many “Christophors” (the saint is present on the outside of the panels, however).

For this composition, too, Rubens opted for diagonal lines. The fulcrum of the compositional layout is the body of Christ, arranged along the diagonal axis, and whose presence is “lengthened” by the large white shroud in which he will shortly be wrapped, a foreshadowing of his deposition in the tomb. The figures who are lowering his body from the cross arrange themselves around him on ladders resting on the horizontal arm of the torture instrument. Two are perched at the top (the figure on the right even holds the shroud with his teeth), another is descending the steps, while St. John, barefoot and covered in a simple vermilion-red robe, is holding Jesus by the legs, and a very blond and very young Magdalene is about to take his feet. Of great emotional impact is the figure of the Madonna, still characterized by her waxy complexion: we see her reaching out, impatiently, her arms forward to embrace the lifeless body of her son. The scene takes place in a gloomy landscape, over which hangs the threat of the dark mounds that occupy the entire sky, except for a small portion in the distance from which the light of sunset is already filtering. In the lower right corner, we see a crude still life piece, with a basin filled with Christ’s blood, the crown of thorns, and the cartouche bearing the words “INRI,” in three languages (Hebrew, Greek, and Latin), added to the cross to taunt Jesus.

The Deposition, despite the fact that it follows theRaising of the Cross by only a couple of years, is already a work that tackles the theme with a different approach: no longer the convulsive violence of the work painted for the church of St. Walpurga, but a more measured painting that tends to internalize the pain, given even the composed expressions of the characters (note the women’s eyes, swollen, reddened, tearful, sad, but capable of expressing a pain as profound as it is calm). All this, however, without sacrificing theemotional impact that the work must be able to elicit. To achieve these effects, Rubens looked, once again, to his Italian experiences. The main model of reference seems to be Federico Barocci’s Deposition, not only because of the formal devices, beginning with the pose of Christ, which is very similar, but also because of the same attempt to make the tragedy delicate: if Barocci had depicted a particularly convulsive scene (the most eventful ever in his production), but had softened it by using a diaphanous and almost ethereal colorism, Rubens, without renouncing the vivacity that distinguished his palette, subjects the movements of the characters to greater control and decides to omit the detail, present instead in Barocci, of the fainting of the Virgin, in order to offer the relative an image of the Madonna and the pious women that is just as heartbreaking, but less theatrical. It is then difficult not to think of Rosso Fiorentino’s Deposition, from which Rubens borrows the detail of Nicodemus clinging to the top of the cross, his arm bent at a right angle, or that of Joseph of Arimathea leaning out of the ladder, reaching out toward the body of Christ: details that the Flemish painter recalls in painting the two figures hanging from the horizontal arm of the cross, who are at a higher level than Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, who instead hold the shroud lower down. Another illustrious precedent is Cigoli’s Deposition now housed in Florence’s Palazzo Pitti: the vertically developed layout and certain details (the posture of St. John, his head slumped on Jesus’ shoulder, the kneeling Magdalene, from behind, at the foot of the cross in quivering anticipation, or the character lowering Jesus from above) might suggest that Rubens had a chance to see the Tuscan painter’s work. In the event, Rubens may also have looked to Cigoli for the sense of clarity that the work, in contrast to Barocci and Rosso Fiorentino, exudes.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Deposition (1611-1614; oil on panel, central panel 421 x 311 cm, side panels 421 x 153 cm; Antwerp, Cathedral of Our Lady) |

|

| Comparison of Rubens’s painting and Federico Barocci’s Deposition |

|

| Comparison between Rubens’ painting and Rosso Fiorentino’s Deposition |

|

| Comparison between Rubens’ painting and Cigoli’s Deposition |

The last painting Rubens made for Antwerp Cathedral is theAssumption altarpiece, the origins of which date back to a commission the artist won in a competition announced in 1611 by outdoing his own master, Otto van Veen (Leiden, 1556/1558 - Brussels, 1629), who submitted a sketch but could do nothing against the flair and energy of his former pupil. Rubens made an early Assumption that, for reasons still unknown, never ended up in the Cathedral and was instead destined for the Jesuit church in Antwerp, while it is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. In 1618 Rubens then presented a new model, the one for the work that would later actually take its place on the Cathedral’s high altar. The following year the cathedral’s dean, Johannes del Rio, undertook all the expenses to create the work, in exchange for a monument inside the church: however, the realization took a long time, the dean passed away in 1624 without having seen the completed work, and Rubens decided only the following year to complete his painting, which was installed on the cathedral’s high altar in 1626.

Of the works created for the Cathedral, theAssumption is by far the most impressive: it is nearly five meters high. The Virgin, the patron saint of Antwerp Cathedral, is carried to heaven by a large group of cherubs supporting her cloud, while in the lower register of the composition the apostles look on in amazement at the scene (one of them, in disbelief, even leans out to get a better look at the interior of the tomb). All around, a few angels complete the swirl of air and clouds that helps make the painting an accomplished example of the most spectacular Baroque painting. Here, Rubens’ model of reference is Titian ’sAssumption in the Basilica dei Frari in Venice, from which he takes the idea of dividing the composition into two registers (one dedicated to the Virgin, the other to the apostles), as well as some elements such as the pose of the Madonna, that of St. John, the arrangement of the apostles around the sarcophagus, and the putti supporting the clouds. However, the differences are also different and substantial: if Titian had wanted to clearly separate the celestial sphere from the earthly one, creating a sort of division with the cloud placed along the entire horizontal axis of the altarpiece, Rubens, on the contrary, continually confuses the two planes, especially where the angels lean against the rocks of the landscape (which, moreover, is present in the Flemish painter’s work: there was instead only sky in Titian’s painting). It is therefore a work cast within the theological debates of the time: not only does it affirm the importance of the figure of Mary, which the Protestants had downplayed, but, in accordance with the dictates of the Counter-Reformation, it lets the role of Our Lady as mediator between the earthly and the divine worlds transpire with great clarity. Finally, there are those who wanted to discern a romantic detail in the woman dressed in red in the background behind the tomb. It may in fact be a portrait of Pieter Paul Rubens’ wife, Isabella Brant, who had passed away at the age of just thirty-four in 1626, just as the painter was about to finish the work: and in this way he may have wished to pay homage to his bride.

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Assumption (1618-1626; oil on panel, 490 x 325 cm; Antwerp, Cathedral of Our Lady) |

|

| Comparison between Rubens’ painting and Titian’sAssumption of the Friars. |

Few places in the world like Antwerp Cathedral boast such a conspicuous and significant presence of works executed by a single great artist who has sealed some of the most important pages in the history of art of all time. Walking through its aisles is therefore a way of getting to know the great Flemish genius: today, those who make a visit to the church undertake, at the same time, a fifteen-year-long journey through the career of the Baroque painter par excellence, discovering his vigor, novelties, peculiarities, technical skills, and iconographic sources. It is a journey that has fascinated travelers of every era, many of whom have filled pages on Rubens’ masterpieces or entrusted their biographers with the account of their emotions: from Alexandre Dumas to the same Walter Scott mentioned at the beginning, from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Eugène Delacroix. And which today never ceases to exert the same fascination.

Reference bibliography

- Joost van der Auwera, Sabine van Sprang (eds.), Rubens, l’atelier du génie. Autour des oeuvres du maître aux Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, exhibition catalog (Brussels, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, September 14, 2007 to January 27, 2008), Uitgeverij Lannoo, 2007

- Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée (ed.), Rubens, exhibition catalog (Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts, March 6 to June 14, 2004), RMN, 2004

- Jay Richard Judson, Rubens: the passion of Christ, Brepols Publishers, 2000

- Simon Schama, The Eyes of Rembrandt, Mondadori, 2000

- Irene Smets, The Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, Ludion Editions, 1999

- Caterina Limentani Virdis, Francesca Bottacin, Rubens from Italy to Europe, Proceedings of the international study conference (Padua, May 24-27, 1990), Neri Pozza, 1990

- Charles Scribner, Rubens, Harry N. Abrams, 1989

- Frans Baudouin, Rubens in Antwerp, Harry N. Abrams, 1977

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.