“Color is not stone.” These simple words, attributed to Pieter Paul Rubens by Jacob Burckhardt, allow us to understand the neuralgic centrality held by the “Father of the Baroque,” but, at the same time, they might limit the analysis of a personality whose boundless culture can be investigated from multiple aspects. German by birth, from a family originally from Flanders but a citizen of the world, Rubens found in ’theFlemish environment (specifically in Antwerp, where for religious reasons he repaired with his family) the primordial basin ofaction in which to make his studies in the humanae litterae and to learn his first pictorial knowledge centered, thanks to the training of his masters (Tobias Verhaecht, Adam Van Noort and Otto van Veen), on Italian figurative culture( Raphaelesque and Michelangelo’sexempla, Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto). The link with Italy was solidified on May 9, 1600, when Rubens embarked on his own journey “beyond the mountains,” which, over a period of eight years, led him to familiarize himself with the major centers of the time such as Venice, Rome, Mantua, Padua, Florence and Genoa.

His sojourn in the “Belpaese” was interrupted at two junctures that led him between 1603 and 1604 to carry out diplomatic activities on behalf of Vincenzo I Gonzaga, duke of Mantua, at the Spanish court of Philip III, and in 1608 to leave Italy for good because of the mournful news from Antwerp regarding his mother’s health condition. A pivotal figure in the artist’s transalpine sojourn was Vincenzo I Gonzaga himself, who, in addition to understanding his undoubted artistic abilities and natural diplomatic disposition (as evidenced by the aforementioned assignment at the Spanish court), also managed to exploit his “clinical eye” for artistic matters: famous, in fact, is the purchase made in 1607 by the duke, precisely on Rubens’ instructions, of Caravaggio’s “scandalous” Death of the Virgin . And it is always the figure of Vincent I that will bring the Flemish master into the orbit of that Republic which, between the 16th and 17th centuries, quoting Fernand Braudel, became the “heart of the Western World System”: Genoa.

The first contact between Pieter Paul Rubens and the ’Genoese milieu occurred on June 2, 1604 when, on his return from Spain, on the orders of Vincenzo Gonzaga, the artist stopped in Genoa to be reimbursed by Nicolò Pallavicino, the duke’s own banker, for expenses incurred during the Iberian trip. A second and more lasting stay had to take place in 1606 when “for some gentle Genoese men he formed in pictures several portraits from nature [...] with love conducted,” of which the Brigida Spinola and the Giovanni Carlo Doria turn out to be emblematic. Moreover, as reported in the Ceremonial Books of the Republic, on July 12, 1607, the master was again in Genoa, specifically in San Pier d’Arena, following again the Duke of Mantua who “lodged in the house of Signora Giulia Grimalda [came] to take some baths at the Marina for a knee he offended.” Such, therefore, must have been the two-year period in which Rubens had the opportunity to observe with due attention “[...] as that Republic is proper to Gentilhuomini, so their buildings are beautiful and most commodious, à proportione più tosto de famigle benché numerose di Gentilhuomini particolari, che di una Corte d’un Principe assoluto.” It was precisely the wonder and fascination aroused in Rubens by the refined private residences of the Genoese nobility that led the artist to devote himself to writing “a meritorious work towards the public good of all the Oltramontan Provinces,” which in 1622, published at his own expense, was first edited under the title of The Palaces of Genoa.

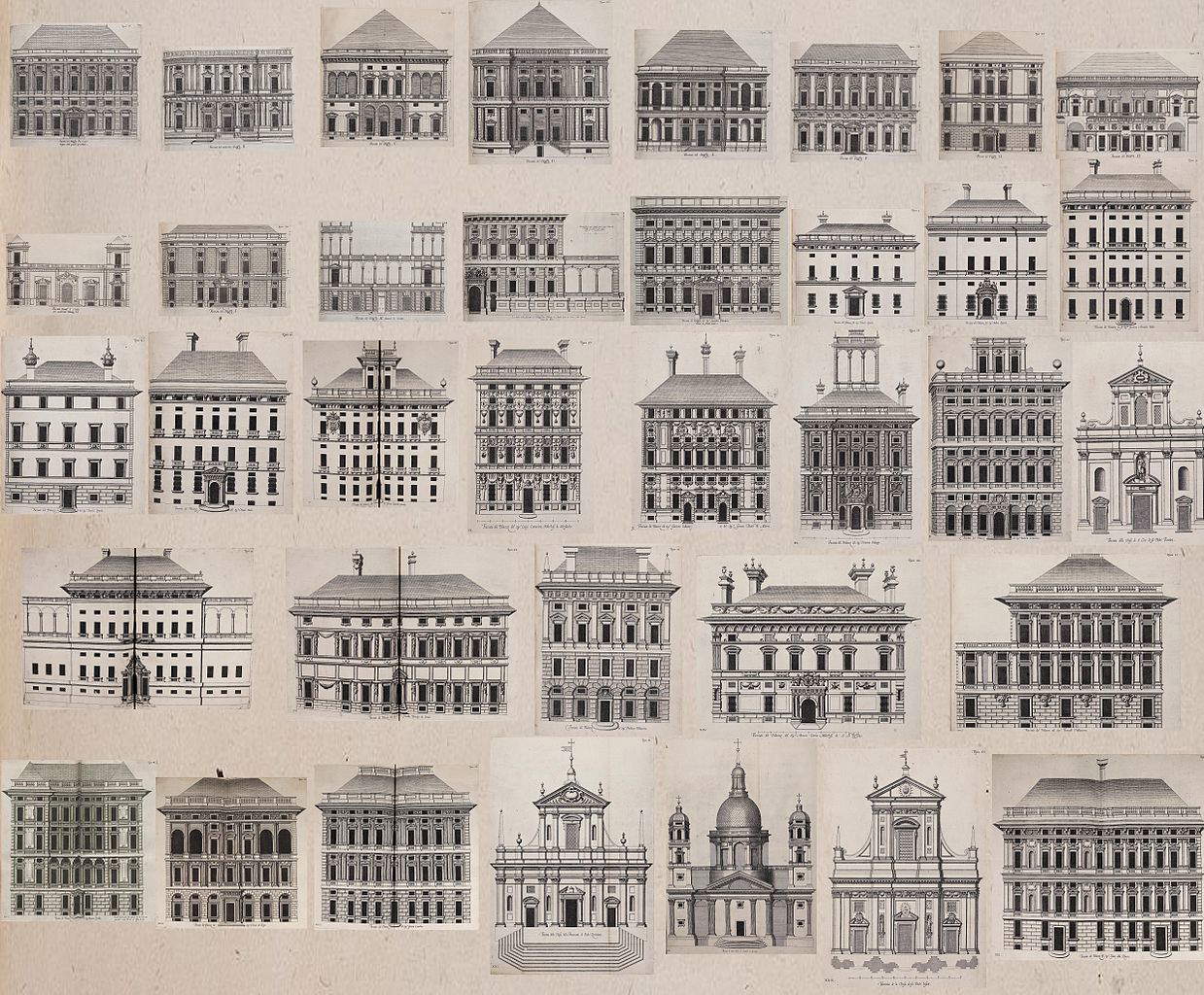

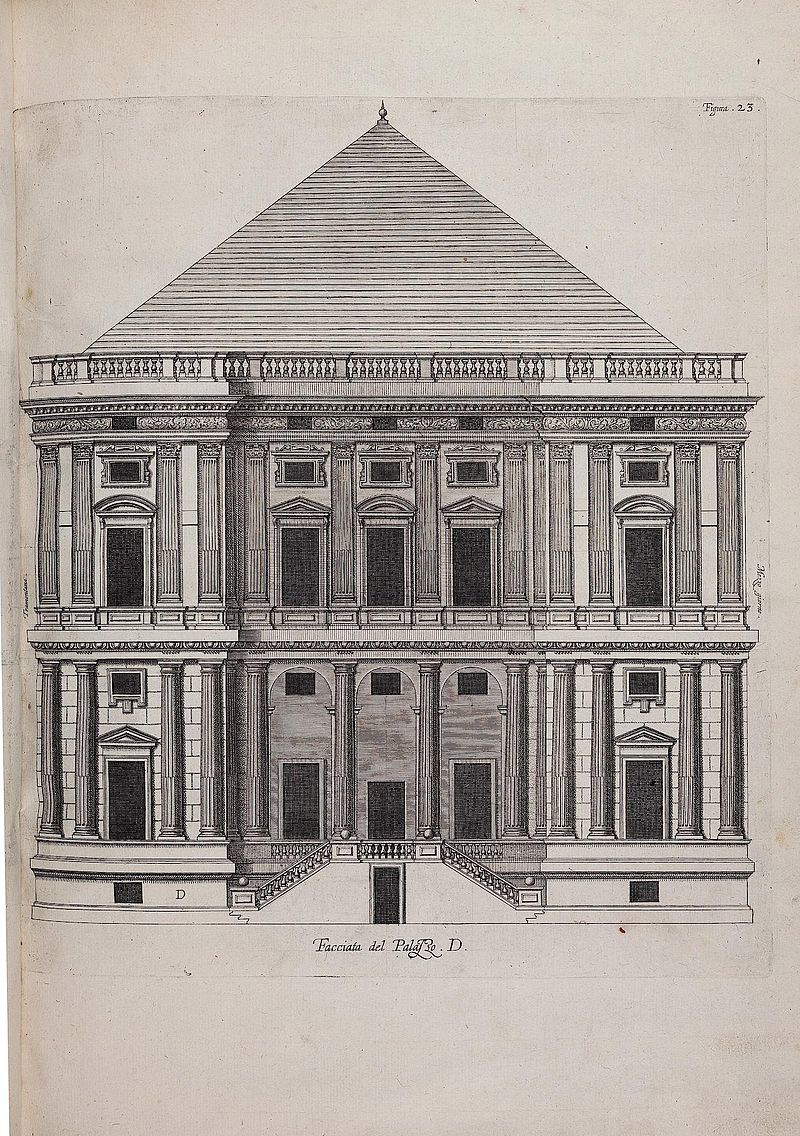

The “Operetta,” so called by Rubens in the introduction to “Benigno Lettore,” was divided into four parts: a foreword, in which the reasons that prompted him to try his hand at writing the work are explained; a following dedication; and the two parts in which, through the re-presentation of architectural plans and sections, the aristocratic palaces investigated are examined. The volume, independently of an uncertain second and close edition estimated at around 1626, by the mid-1630s illustrated to the general public as many as 31 palaces and 4 churches of the Genoese urban fabric, for a total of 139 plates.

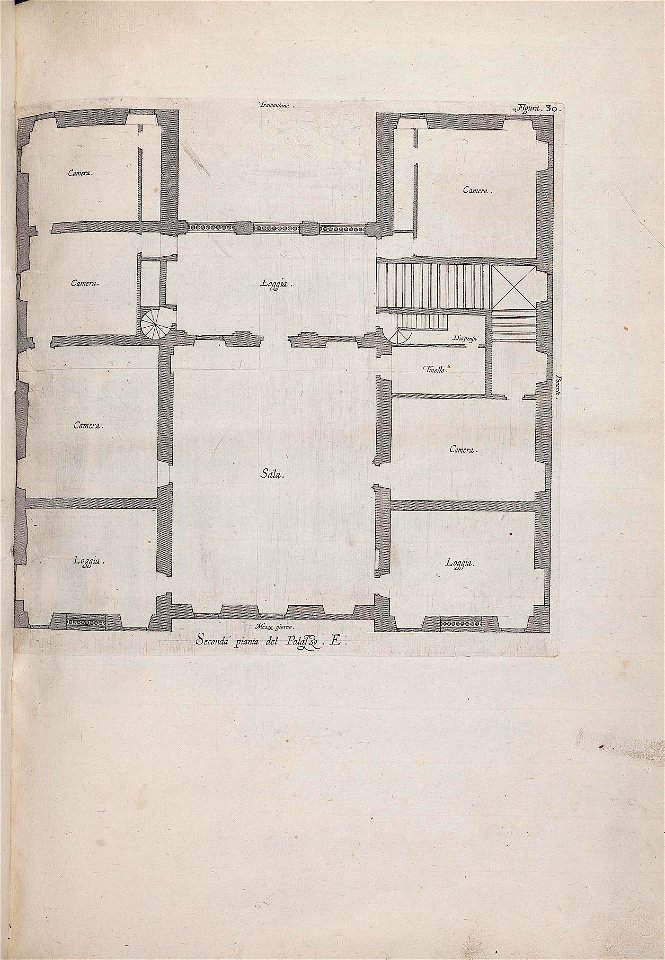

As outlined in the introduction to The Palaces, underlying the publication was the desire to produce an “Operetta” whose main purpose was to educate the Antwerp bourgeoisie on how “by abolishing the manner of Architecture, which is called Barbara, ò Gothica; [...] true symmetry [...] in accordance with the rules of the ancients, Graeci and Romans” could be applied not only to large public buildings but also to “private buildings, then that in their quantity subsite the body of the whole city.” For Rubens, therefore, a pivotal purpose became demonstrating howRenaissance ’architecture could also be applied to the Nordic housing culture whose aristocracy, by multiple tangents, was not particularly dissimilar to the Genoese. Moreover, there is no doubt that the master must have been fascinated by how the language of the well-known Perugian architect Galeazzo Alessi (a pupil of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and “son” of that Roman school influenced by the likes of Baldassare Peruzzi) lent itself to “solutions of great compositional intelligence [...] constantly aimed at overcoming the narrowness of medieval spaces.” In fact, the rigorous Alessian model generated a dwelling with “the shape of a solid cube with a salon in the middle” whose floors, centered precisely on large reception halls, were connected by large monumental staircases that, comparable to a more refined system of “terracing,” enabled the architects to obviate the age-old problem of building “on the coast,” arising from Genoa’s particular orography.

The care with which the Genoese nobles lavished in the construction of their palaces resided, moreover, in the desire to give life to an abode that, mirroring their political, diplomatic and cultural power, could become the ideal setting for welcoming new “guests/clients” with whom to make profitable economic agreements. Otium and negotium, therefore, found in Genoese noble residences a perfect balance that Rubens was able to readily perceive and report, through the reproduction of plans and elevations, in his own manual. Thanks to Mario Labò ’s studies, we have been able to understand how the architectural engravings, the true protagonists of the work, were not exclusively “collected by me in Genoa, with qualque fatigue and expense et alcun buon riscontro di poterermi prevalere in parte delle altrui fatiche,” as Rubens himself declared in the introduction, but were also made by the engraver Nicolaes Ryckmans, the artist’s own collaborator.

The second brief entry in the volume sees the “Most Humble Servant” (as Rubens calls himself) dedicate the work to “Illustris. Signor [...] Don Carlo Grimaldo,” nephew of Ambrogio Spinola (a victorious condottiere in the taking of Ostend in 1604 and an affectionate friend of Rubens), as well as son-in-law of Barnaba Centurione Scotto, owner of the Sampierdarenese villa known as “del Monastero” in which Vincenzo I Gonzaga was hosted in 1600, and still nephew of the aforementioned Giulia Grimaldi. Rubens, wishing to have done something pleasing with the publication of such a manual, asked Grimaldi to “give through his favor some reputation to this little work: which even if minimal, [...] deals with things concerning the honor of his homeland; and will make the world believe in my singular affection towards it.” The “affetion” that Rubens wants to show the world regarding the Republic’s ingenious housing solutions is manifested in the two parts, the true heart of the volume, in which the palaces investigated are examined through refined engravings.

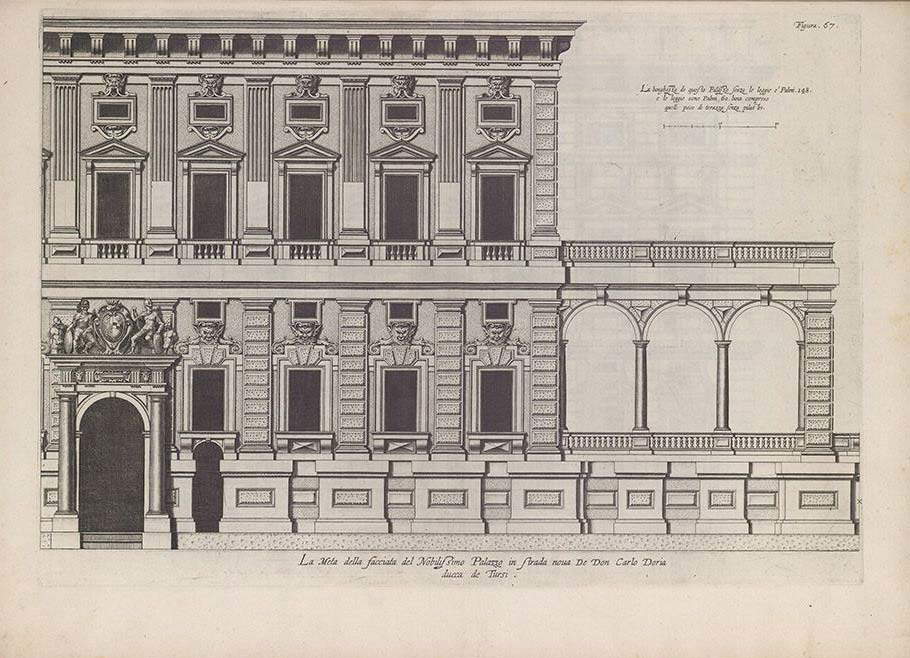

The first part consists of twelve palaces that, mainly located between Strada Nuova (5), a more generic city center (5) and the suburban villa areas-Sampierdarena (2) and Albaro (1)-describe the different architectural solutions proposed. What is striking, in addition to the timely technical description of the plans and sections (which is why the term “manual” is always more appropriate), are the names by which the buildings are identified. These, in fact, turn out to be indicated not by the names of the owners but through the ’use of letters: the motivation for this choice is explained directly by Rubens himself, who indicates to the “Benigno Lettore” how "We have not placed the names of the Masters because everything in this world Permutat dominos, et transit in altera iura." This choice, however, is not homogeneous throughout the volume since, already in the first part, the last two palaces described present the names of the owners: Palazzo di Don Carlo Doria duca di Tursi and Palazzo di Agostino Pallavicino.

The motivation, although not made explicit by Rubens, may lie in the fact that the two buildings described belonged to two of the greatest local personalities: the first, now the seat of the Genoa City Council, was built starting in 1565 at the behest of Nicolò Grimaldi known, due to his considerable wealth, as the “Monarch,” and not coincidentally built on two plots of land (which is why, given the vastness of the symmetrical elevation, Rubens reports only a part of it); the second, made by Agostino Pallavicino, a banker but above all ambassador to Charles V and senator of the Republic, belonged to that family with which, perhaps more than any other, Rubens had interwoven solid and profitable commissions that, among others, led him to the realization (on commission precisely from his sons Nicolò and Marcello) of the already mentioned Circumcision as well as The Miracles of Blessed Ignatius of Loyola.

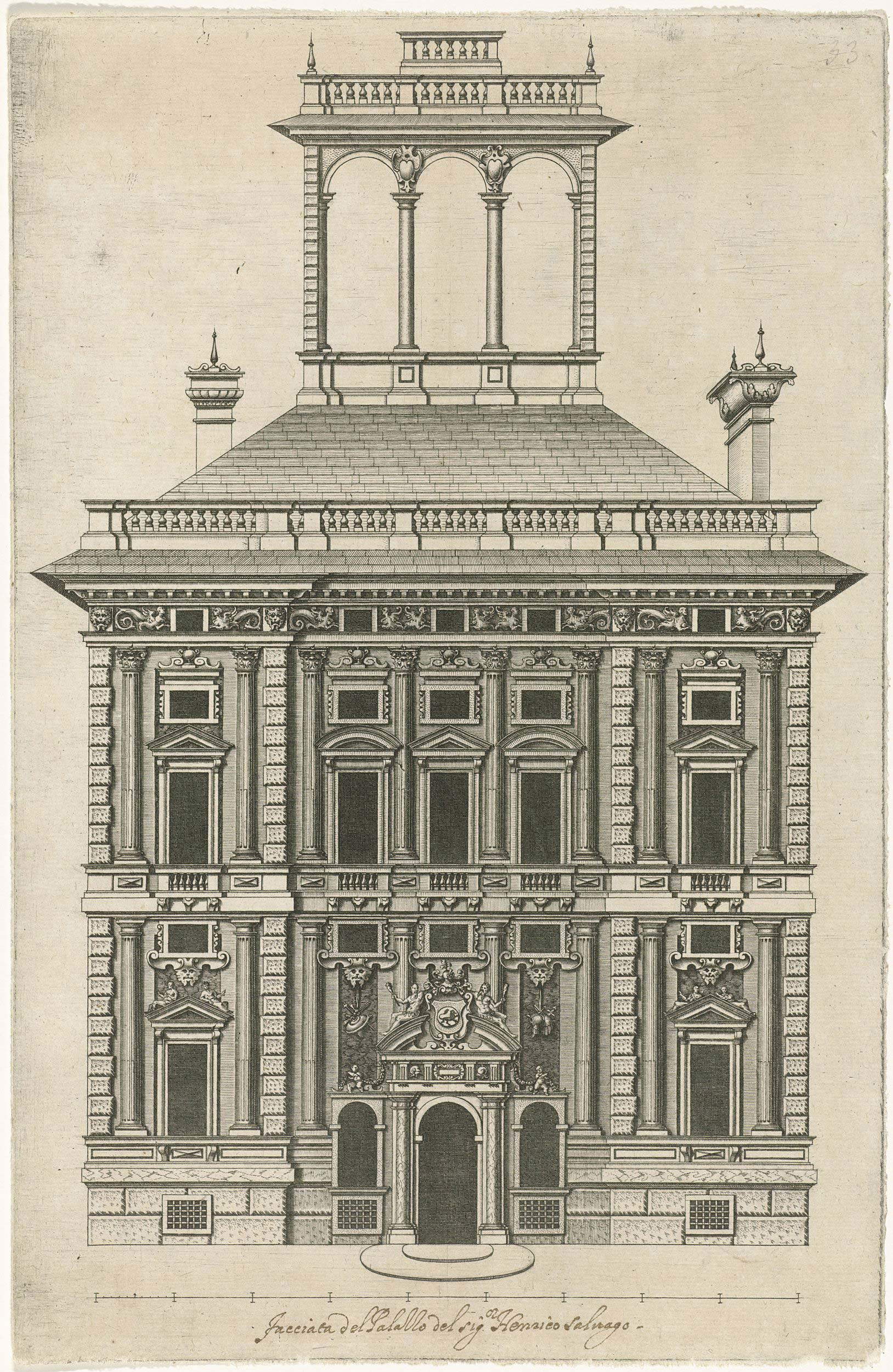

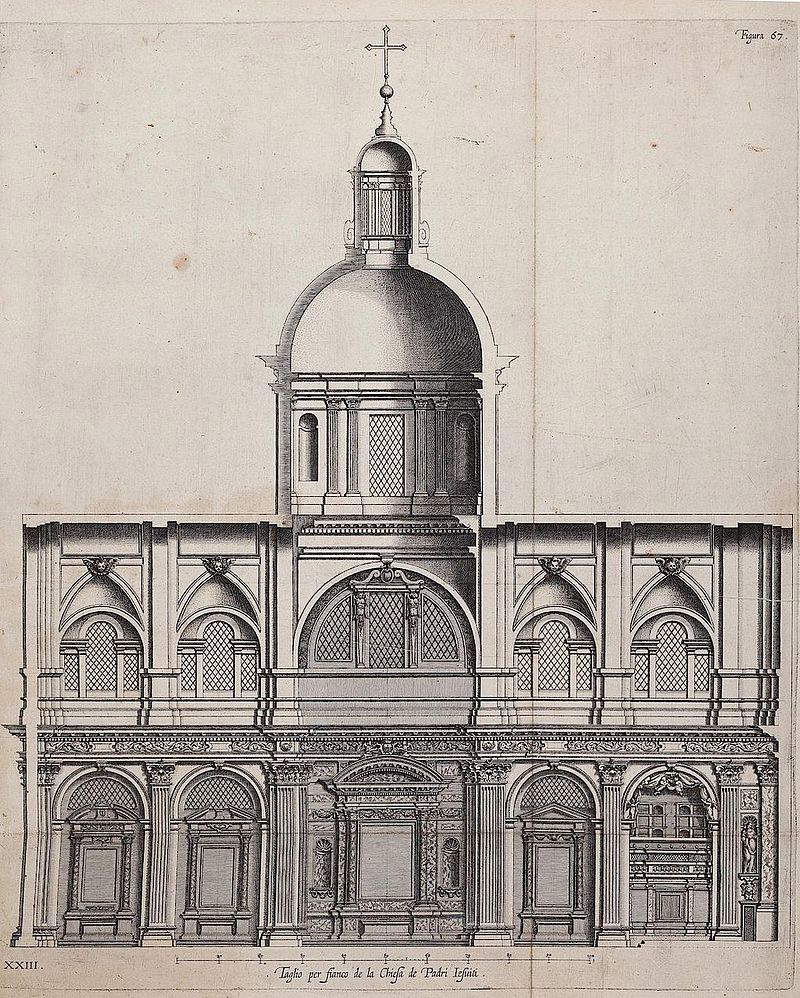

The second part of the discussion goes on to examine 20 private palaces (identified through the names of the owners) to which the artist adds the description of as many as 4 churches. The private buildings described by Rubens in this section no longer concern only the residences of the Old Nobility (Pallavicino, Spinola, Doria) but refer to buildings belonging to the New Nobles (Balbi, Saluzzo, Adorno): such a conscious choice allowed Rubens to provide evidence of the modus aedificandi based on the architectural evolution of sixteenth-century models, of which the dwellings facing the "Strada delli Signori Balbi" are emblematic examples. This distinction, moreover, makes it possible to highlight a political climate in which, following the late sixteenth-century reforms - above all the Casale Accords of 1576 - the discrepancy between Old Nobles and New Nobles slowly leveled off, testifying to how Rubens was able to grasp the progressive socio-political changes that took place between the early seventeenth century and the 1530s. The particularity of the second part of the Palazzi, moreover, lies in the architectural description reserved for the religious buildings among which, for obvious reasons, the Chiesa de li Padri Iesuiti stands out for its abundance and attention to detail, which, precisely because of the presence of the Circumcision and the Miracles of St. Ignatius, appears described, unlike the others, with no less than two sections: transverse and longitudinal.

The work, given its uniqueness, was the subject of successive editions (1663, 1708, 1755, 1922) among which stands out the one of 1652 (the first made after the master’s death), which, by the will of the printer Jan Van Meer, saw the two sections of the volume being renamed as follows: Ancient Palaces of Genoa collected and designated by Pietro Paolo Rubens and Modern Palaces of Genoa collected and designed by Pietro Paolo Rubens. The volume, therefore, is outlined as a true architectural manual resulting from a distinguished personality who, in addition to being a painter, diplomat and art connoisseur, also held the role of a fine “treatisee” capable of testifying “to the world” the realization of housing solutions conceived with extreme uniqueness for the private dwellings of a nobility that, by political and economic importance, held the reins of much of Europe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.