by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 31/05/2016

Categories: Works and artists

- Viaggi / Disclaimer

In Rome's Trastevere district is the little-known church of Santa Maria dell'Orto, the church of the people, shopkeepers and merchants of the city.

If we were to take one hundred people, and ask each of them for a list of ten places to visit in Rome, we could bet, with very good odds of winning, that none (or maybe one or two) would point to the church of Santa Maria dell’Orto. This is why, by the way, we are against “ten things to do in” style articles: they are necessarily exclusionary. And Santa Maria dell’Orto would very hardly be included in a list: the point, in fact, is that this religious building, located in the heart of Trastevere, is cut off from all mass itineraries. Its location, far from the streets of bustle and tourism, probably does not play to its advantage: whether this is good or bad is for the reader’s sensibility to judge. Nor have the lengthy restorations that the building has had to undergo several times in recent years helped: threatened by ill-considered expansions of surrounding buildings, the church had to undergo consolidation work, which lasted at first from 1984 to 1995, and then again from 2011 to 2013. Today, finally, the church can present itself to the Romans (and not only to them) in all its magnificence, the result of centuries of contributions offered... by the people!

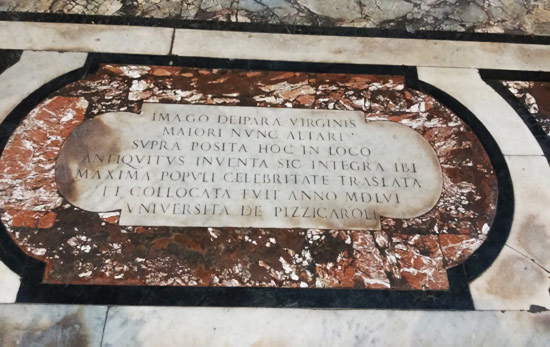

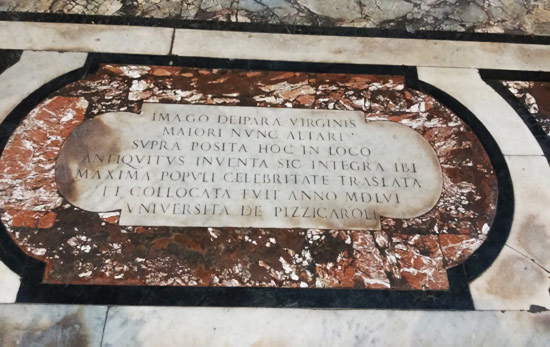

Yes, because Santa Maria dell’Orto is not a church created by the will of a pope or a prince, nor are the owners of its chapels members of families of the Roman nobility. None of that: Santa Maria dell’Orto is the church of the Trasteverini, of the people, of the workers. And popular are its origins: these are said to be due to an event believed to be miraculous. In the fifteenth century, the area on which the building stands today was filled with fields, land and vegetable gardens (hence the name of the church): tradition has it that, around 1488, a seriously ill farmer stopped in front of an image of Our Lady that was on the wall of a vegetable garden. The farmer allegedly made a vow to Our Lady, and was miraculously healed: the local people therefore decided to build a small chapel in the late 15th century to celebrate the event. In order to better organize the cult of Our Lady of the Garden, it was decided to assemble a Confraternity, which would promote devotion to the Virgin and follow the building of the church, inside which, on the high altar, the image that would begin the building’s history can still be seen. The confraternity was officially recognized in 1492 by Pope Alexander VI, and its activity continues to this day: the Venerable Archconfraternity of Santa Maria dell’Orto (the elevation to “archconfraternity” dates back to 1588) is the sodality that continues to care for the church of Santa Maria dell’Orto.

|

| The inscription commemorating the placement in the church of the miraculous image |

|

| The high altar of the church of Santa Maria dell’Orto in Rome |

|

| The nave |

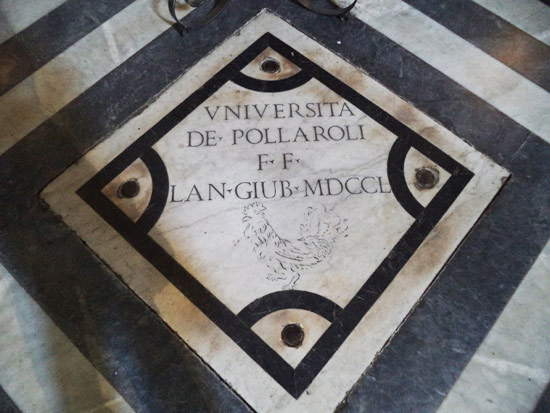

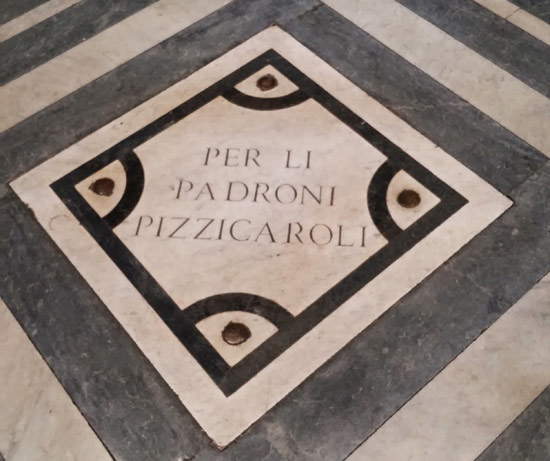

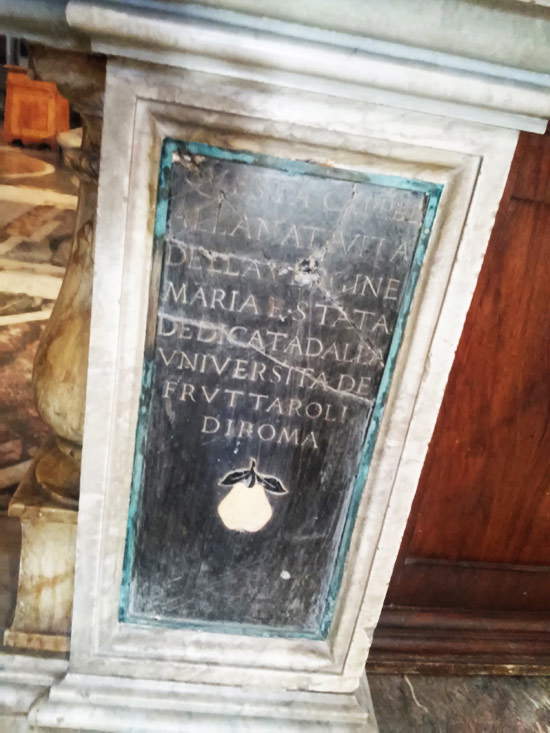

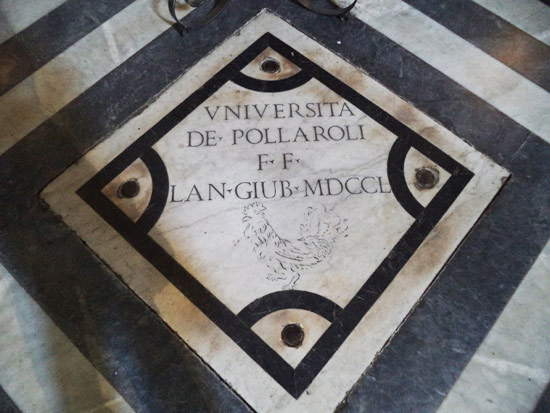

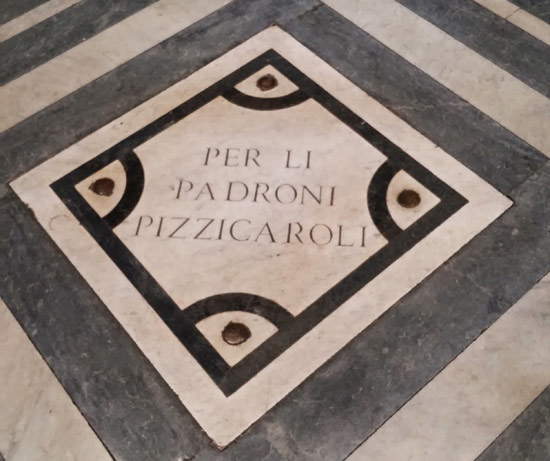

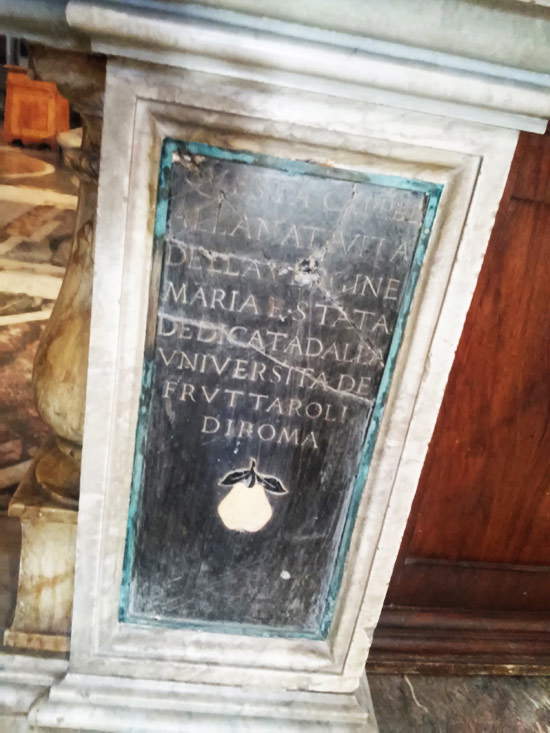

The confraternity, over the centuries, was also able to benefit from a very special help: that of the Universities of Arts and Crafts, or workers’ guilds (what, to be clear, today we would call “trade associations”). We must not forget that, in this area of Rome, the port of Ripa Grande, the city’s river port, was located in ancient times: we can therefore imagine how the neighborhood was very lively, since it was an important junction for trade, and that it was densely populated, by people mostly from low social backgrounds. At the port of Ripa Grande all goods destined for the city disembarked: these were mainly foodstuffs that supplied stores all over Rome. The area was therefore a regular destination for vegetable gardeners, millers, meat and poultry sellers and various merchants, who therefore began to think about finding a reference church. The choice could only fall on Santa Maria dell’Orto: thus, the guilds joined the confraternity in its work. Tradition identifies twelve guilds that gave luster to the building by bearing the expenses for the stucco work, paintings, and decorations: the ortolani (vegetable growers), the pizzicaroli (i.e., charcuterie makers), the fruttaroli (fruit growers), the merchants, the sensali (i.e., brokers in the agricultural products trade), the molinari (i.e., millers), and the vermicellari (i.e., pasta makers: vermicelli, as is well known, is a type of pasta), pollaroli (the poultry sellers), scarpinelli (the shoemakers), mosciarellari (the chestnut sellers: the “mosciarella” is a dried chestnut typical of Rome and its environs), vignaroli and barilari. To the universities that brought together the “masters,” that is, the owners of the businesses, were sometimes added the universities of the “garzoni”: it happened for the molinari, pizzicaroli, ortolani and vermicellari. Every painting, every stucco, every decoration, in short, every corner of the church can easily be traced back to the university that... “sponsored” it: in fact, there are inscriptions everywhere that refer to the corporation that financed an intervention. The most conspicuous ones are, probably, the inscriptions decorating the floor. With the name of the university often flanked by a symbol, so that even those who could not read could understand who had taken on the burdens of the undertakings. The prize for the most conspicuous floor decoration, however, goes to the orchardists, with their 1747 marble inlay filled with all kinds of fruit, which is on display right in front of the high altar.

|

| The floor inscription of the University of the Pizzicaroli |

|

| University of the Pollaroli |

|

| University of the Ortolani |

|

| University of the Scarpinelli |

|

| “Per li padroni pizzicaroli.” |

|

| The marble inlay of the University of the Orchardists |

|

| Portal funded by the University of the Pizzicaroli |

The church is so lavish to us today, often to the point of excess, because the twelve universities, in fact, competed to endow the church with the most beautiful and luxurious decorative apparatuses, with the funds they could dispose of thanks to the contributions of the members: everything we see in the church is, in essence, the result of the work of salumieri, ortolani, fruttivendoli, calzolai, and so on. That is why Santa Maria dell’Orto is considered the church of the people: here, the nobility never intervened. But it would be wrong to think that the humbler classes of the population were not endowed with taste: it is enough to think that the design of the façade was entrusted to one of the most up-to-date and elegant architects of his time, Jacopo Barozzi, known as il Vignola (Vignola, 1507 - Rome, 1573), who created the elevation starting in 1566. The façade is thus a summa of elements typical of the Vignola style: it presents a first level in which refined pilasters crowned by Ionic capitals alternately divide the external niches from the entrance doors to the building. The two side doors are surmounted by triangular tympanums, while the main portal is flanked by two columns, also in the Ionic style, supporting a strongly projecting curved tympanum. The entablature with the inscription that tells us in a few words the history of the building divides the lower order from the upper one, consisting of a pediment (with a large window surmounted by a clock, and subdivided by Corinthian pilasters) connected at the lower level by two volutes, typical of Jacopo Barozzi’s repertoire. Completing the ensemble are small travertine obelisks, also typical of Vignola’s lexicon: we have six of them (three on each side) flanking the pediment at the pilasters, and five surmounting it.

|

| The facade of Santa Maria dell’Orto in Rome, Trastevere. |

The interior, as anticipated, is meticulously lined with inscriptions attesting to which university a group of paintings, a decoration, or a portal is due. Upon entering, on the right, the first chapel we find is shared by two universities, that of the matchmakers and that of the merchants, and is dedicated to theAnnunciation. On the altar, in the center between a St. Gabriel by Virginio Monti from 1875 and a St. Joseph by Giovanni Capresi from 1878, we can see a painting by Federico Zuccari (Sant’Angelo in Vado, 1539 - Ancona, 1609), dating from the summer of 1561 (but restored in 1998), depicting the moment when the archangel Gabriel makes the announcement to the Madonna. It is a youthful work: the artist was only twenty-two years old at the time, and he produced a simple, essential but elegant painting, in line with the classicist style that was still influenced by the lesson of Raphael, who had died forty-one years earlier. Also by Federico Zuccari, in collaboration with his brother Taddeo (Sant’Angelo in Vado, 1529 - Rome, 1566), are the frescoes that decorate the apse basin, with Stories of the Virgin: they were financed by the University of the Fruttaroli (the marble inlay on the floor in front of the high altar and the Ave Maria symbol, consisting of festoons of fruit, that stands out in the center of the large window of the apse remind us of this) and date from the same period. On the left, we see the Marriage of the Virgin at the top and the Nativity at the bottom, while on the right we find the Visitation and the Flight into Egypt. The scenes of the Marriage and the Visitation would be attributable to Frederick’s hand. As the art historian Claudio Strinati had written, these paintings by Federico Zuccari are “sober, conducted with the evident intention of respecting the canons of symmetry, order of composition, and balance,” and the young artist’s hand is “happy but firm, the drawing turned, sure,” even if “puny in the final outcome.” However, a very high "sense of the dignitas“ of ”what is represented" ensues: in other words, the loftiness of the subjects depicted is fully emphasized by the fluid, yet classical and rigorous style of the painter from the Marche region.

|

| The right aisle of Santa Maria dell’Orto |

|

| Federico Zuccari, Annunciation (1561) |

|

| The paintings of the apse |

|

| Dedication of the paintings of the apse (University of the Orchards) |

|

| The Ave Maria of the University of the Orchardists |

Returning to the first chapel and proceeding forward, we encounter the chapel of the University of theVermiculators, dedicated to St. Catherine of Alexandria and decorated by Filippo Zucchetti (Rieti, 1648 - 1712), who painted a Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine for the altar, flanked by a St. Paul and St. Peter by an anonymous 18th-century artist.

|

| Filippo Zucchetti, Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (1711). |

By contrast, it is entirely the work of Giovanni Baglione (Rome, 1573 ca. 1643) to decorate the chapel of theUniversity of the Vignaroli, dedicated to Saints James, Bartholomew and Victoria. The Roman artist, a great rival of Caravaggio, had already worked in the church, between 1598 and 1599, taking care of the realization of some scenes of the Life of Mary on the walls of the apse (they precede the Zuccari frescoes mentioned above) and would return to work here in the following years as well. So those who would like to know the development of Giovanni Baglione’s art could get a rather complete idea here: we have in fact early works (those in the apse, probably the first we know of the artist), works of his full maturity and works from the very last phase of his career (in the chapels). Those considered most interesting are the canvases we find in the chapel of theUniversity of Ortolani, dedicated to Saint Sebastian: here, Giovanni Baglione created, in 1624, a Saint Sebastian cared for by angels for the altar, and two additional saints (Anthony of Padua and Bonaventure) for the side aisles. The eclecticism that distinguished, for a good part of his artistic career, Giovanni Baglione’s style can be inferred from the elements discernible in the paintings: a calm naturalism, with an almost classical flavor, of Carracci derivation is added to a luminism of Caravaggio observance and a colorism that refers to Venetian painting. More tired, however, appear the achievements of the chapel of the vignaroli, namely a Madonna and Child with Saints, the Martyrdom of a Deacon Saint and the Martyrdom of St. Andrew (we are in 1630) and those of the chapel of theUniversity of the Scarpinelli, dedicated to Sts, Ambrose and Bernardine of Siena, in which we find a Madonna and Child with Saints on the altar and two stories of Saints Charles Borromeo and Ambrose on the side walls ( St. Charles Borromeo cures the plague victims and St. Ambrose drives the Arians out of Milan, respectively). These are the last works of the Roman painter, created in 1641: the repertoire by this time had become trite, lacking original ideas and also rather low in quality.

|

| Giovanni Baglione, Madonna and Child with Saints (1630) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, Martyrdom of a Deacon Saint (1630) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, Martyrdom of Saint Andrew (1630) |

|

| Paintings by Giovanni Baglione: left, Madonna and Child with Saints. On the right, Saint Ambrose expels the Arians from Milan (1641) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, Saint Charles Borromeo cures the plague victims (1641) |

|

| Paintings by Giovanni Baglione: on the left, Saint Bonaventure. On the right, Saint Sebastian cured by angels (1624) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, Saint Anthony of Padua (1624) |

In the left aisle, between the two chapels decorated by Giovanni Baglione, we find that of the Company of the Young Pizzicaroli, the grooms of the delicatessen workers: the altar is decorated with a canvas by Corrado Giaquinto (Molfetta, 1703 - Naples, 1766), dated 1750, which has the Baptism of Christ as its theme, while the side walls are decorated with two canvases dated 1749 by Giuseppe Ranucci, representing the Preaching and the Beheading of the Baptist (the chapel is in fact dedicated to St. John the Baptist). Before reaching the transept, we can return to the nave and look up at the ceiling: the splendid vault bears a work by Sicilian Giacinto Calandrucci (Palermo, 1646 - 1707), anAssumption of Mary from 1706 framed by abundant gilded stucco. One legend has it that gold arrived in Rome on return from Christopher Columbus’ expedition to America was used for the gilding: however, there is no historical evidence for this.

|

| The vault with the Assumption of Mary by Giacinto Calandrucci (1706). |

|

| The left aisle of Santa Maria dell’Orto. |

|

| Left: Giuseppe Ranucci, Beheading of the Baptist (1749). Right: Corrado Giaquinto, Baptism of Christ (1750) |

|

| Giuseppe Ranucci, Preaching of the Baptist (1749) |

Reaching the transept, we come across two chapels (on the left, that of the Molinari, dedicated to St. Francis, and on the right, that of the Pollaroli, dedicated to the Most Holy Crucifix) entirely decorated with frescoes by an interesting exponent of late Mannerism in Rome, Niccolò Martinelli known as il Trometta (Pesaro, c. 1535-Rome, 1611). Martinelli, who trained in the groove of zuccaresca painting, decorated the two chapels with stories of St. Francis and stories of the Passion, respectively, executed between 1591 and 1595. These are, again, calm and sober paintings, influenced by the classicism that constituted the predominant taste of the time, declined in these cycles also with a certain sense of monumentality.

|

| Niccolò Martinelli called the Trometta, Stories of the Passion (detail, 1591-1595) |

|

| Niccolò Martinelli called the Trometta, Stories of Saint Francis (detail, 1591-1595) |

|

| The Chapel of Saint Francis |

We are therefore on our way to the exit. However, before entering the door, which is surmounted by a large 19th-century organ donated by the University of Molinari, we remembered a small detail we had read in one of the many web pages dedicated to the church (in fact, fortunately, Santa Maria dell’Orto is experiencing a sort of rediscovery by art enthusiasts): the most bizarre gift donated to the church by the guilds would not be one of the works we have mentioned so far. Yes, because in the seventeenth century, theUniversity of Pollaroli would give the fraternity a curious wooden turkey. We searched the entire church for it, but to no avail: consider that we spent about an hour inside the house of worship. Intrigued by this unusual sculpture, we asked one of the custodians about it: it seems that the wooden bird is hidden in the sacristy rooms, and can only be seen with a booked visit by appointment. The next goal to be achieved, then, when we return to the magical and characteristic neighborhood of Trastevere, will be to be able to see the legendary turkey jealously guarded in Santa Maria dell’Orto!

|

| The organ of the Molinari University |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.